As Alien’s John Hurt will tell you, births can be painful things. But when the moving picture popped out of the tummy of the 19th century and scurried off in the general direction of Paris, London and California, the only sensations were novelty and excitement. As the new medium took shape, pioneers like the Lumière brothers, Eadweard Muybridge and Georges Méliès blew minds and popped eyeballs with whirring, humming contraptions that projected moving images as if by a kind of devilish sorcery. As Empire’s Film Studies 101 gets underway, it’s time to go back to the very beginning. Welcome to a wonderful world of inventors, contraptions, nickelodeons, even a magician or two. Don your scrubs for the birth of cinema.

A is for L'Arrivée D'Un Train En Gare De La Ciotat

If this historic short, one of the very first projected films in movie history, was released now we'd like to think it'd be called Louis Lumière's Panic Station. Baldly subtitled "Lumière No. 653", its brief footage reverberated through the infant art form like a shockwave. The train pulls into the station. The train stops. The man in the hat glances into the camera. There's no sign of either Denzel Washington or Chris Pine. Nothing explodes. Regardless, audiences in 1895 gasped as the action unfolded over 50 short seconds. Famously, although probably apocryphally, a gathering in Lyon turned from the screen in raw terror, expecting the locomotive to crash through the proscenium. Martin Scorsese's Hugo - your first homework, folks - lovingly recreated this scene and captured the unique thrill of cinema's earliest actioner.

B is for The Biograph Company

If you know that D. W. Griffith’s motion picture house was called The Biograph Company, congratulations, you’re a proper film buff. If you know that its full name was ‘The American Mutoscope And Biograph Company’, congratulations, you’re Pauline Kael. The Biograph was set up in 1895 by W. K. L. Dickson, disgruntled ex-employee of Thomas Edison, with the help of two inventors (Herman Casler and Henry Marvin) and a business-minded individual named Elias Koopman. Up until its bankrupcy in 1928, its output of more than 3000 shorts and 12 feature films helped drive cinema forward, launching the careers of Blanche Sweet, Lillian Gish, Lionel Barrymore and Mary Pickford along the way, and giving Griffith scope to refine filmmaking ideas like the close-up, the cross-cut and flashback. It also helped foster a much less savoury notion – the monopoly – when it joined forces with Thomas Edison to form the Motion Picture Patents Company to squeeze competitors out of the American market.

C is for Celluloid

Poor and "not especially gifted", at least academically, New Yorker George Eastman hardly seemed bound for glory as a young, $15 a week bank clerk. Years later as a wizened businessman with a company, Eastman Kodak, bearing his name, riches accrued and mighty success achieved, it's safe to say he'd proved those judgments a little hasty. His creation of a commercial transparent roll of celluloid made Thomas Edison's camera possible. "Putting film on a roll rather than a slide was a pretty good idea," he might have thought to himself, sipping from his diamond-encrusted goblet. "I wonder why no-one else thought of it?" Or, at least, he would have done had he not been a mighty philanthropist who gave away most of his wealth - $100m in total - by the time of his death in 1932.

D is for Daedalum

It's better known as the zoetrope but Bristolian maths teacher William George Horner originally named his magical viewing box after ill-fated Greek flying fellow Daedalus. The device, which created the illusion of motion using painted images and a spinning drum, built on the advances of the Belgian-born phenakistoscope, opening it to a communal audience. For 19th century punters, the affect must have been akin to watching a Tony Scott movie through a salad spinner. Later, American inventer William F. Lincoln renamed it the 'zoetrope' ('wheel of life') and lo, Francis Ford Coppola's production company had a name.

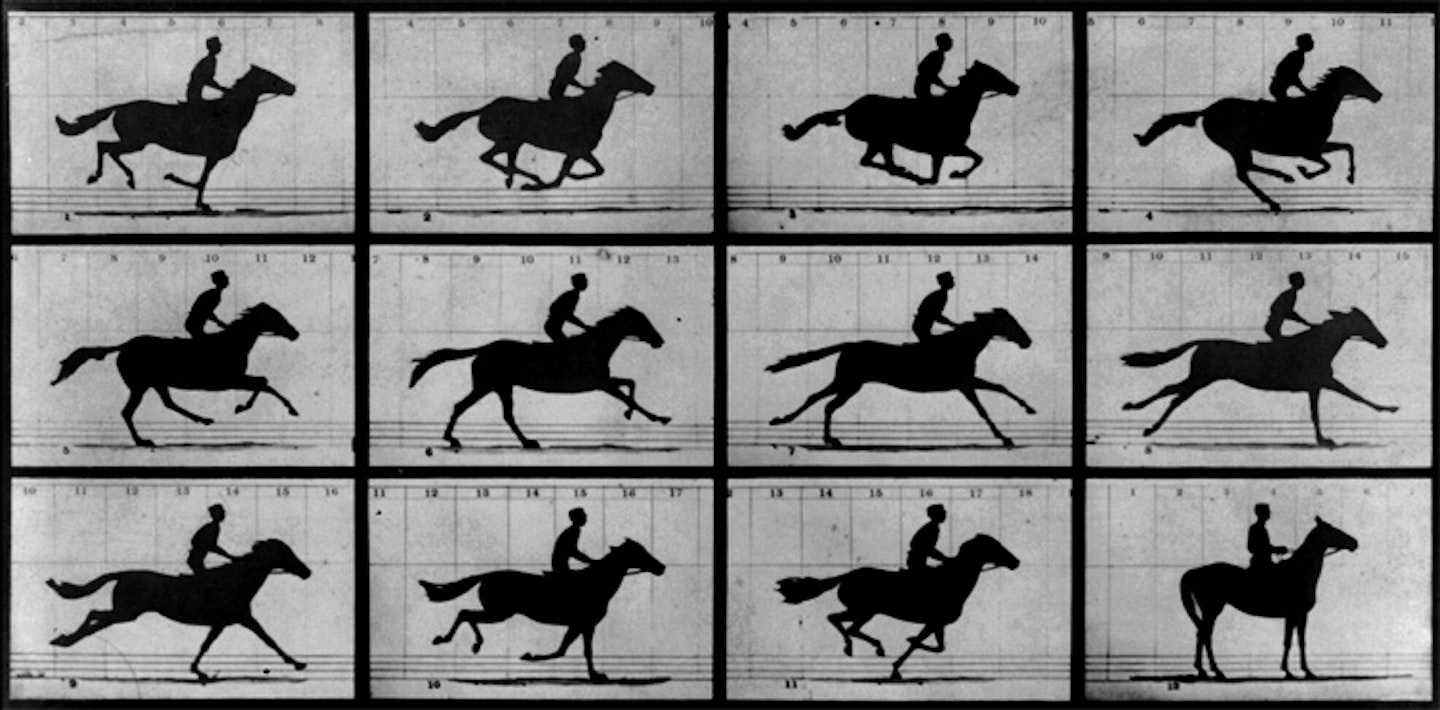

E is for Eadweard Muybridge

With his gutsy experimentations and big Santa beard, Muybridge is justly known as the father of the motion picture. Born Edward Muggeridge to Surrey grain merchants, he moved to Gold Rush-era San Francisco, initially as an ambitious 25 year-old bookseller, then as a portrait photographer and wilderness chronicler for the US government. Like the Werner Herzog of the still photo, he went to great lengths to get 'the shot', lugging his view camera up mountains and down ravines and probably wrestling the odd bear along the way. But it was a series of sea-level snaps that brought him eternal fame. Using 12 cameras rigged up to wires and stretched across a Palo Alto race course he captured a horse in full flight, winning a $25,000 bet for ex-California governor Leland Stanford - that all four hooves are airborne simultaneously during gallop - and a place in film history. "It was a brilliant success," one reporter raved. "The horse was exactly pictured." A year later he invented the zoopraxiscope, an upgrade on the zoetrope that projected images from rotating glass disks using light from an oxy-hydrogen lantern. Basically, he can spell 'Edward' however he wants.

F is for Firefighters

The idea that film could depict two events unfolding simultaneously, or that anything at all could be happening off screen, was before Edwin S. Porter's Life Of An American Fireman. The Lumière brothers got the camera rolling in the late 19th century and D. W. Griffith would soon use it to create entire worlds, but Porter was the man who established filmmaking grammar, the cross-cut in particular. American Fireman, while hardly Backdraft, rattles along apace, as a damsel in distress and her sprog await rescue from Newark's finest. She is either, (a) rescued by the brave fireman and lives happily ever after, or, (b) burnt to a cinder. Answers on a postcard!

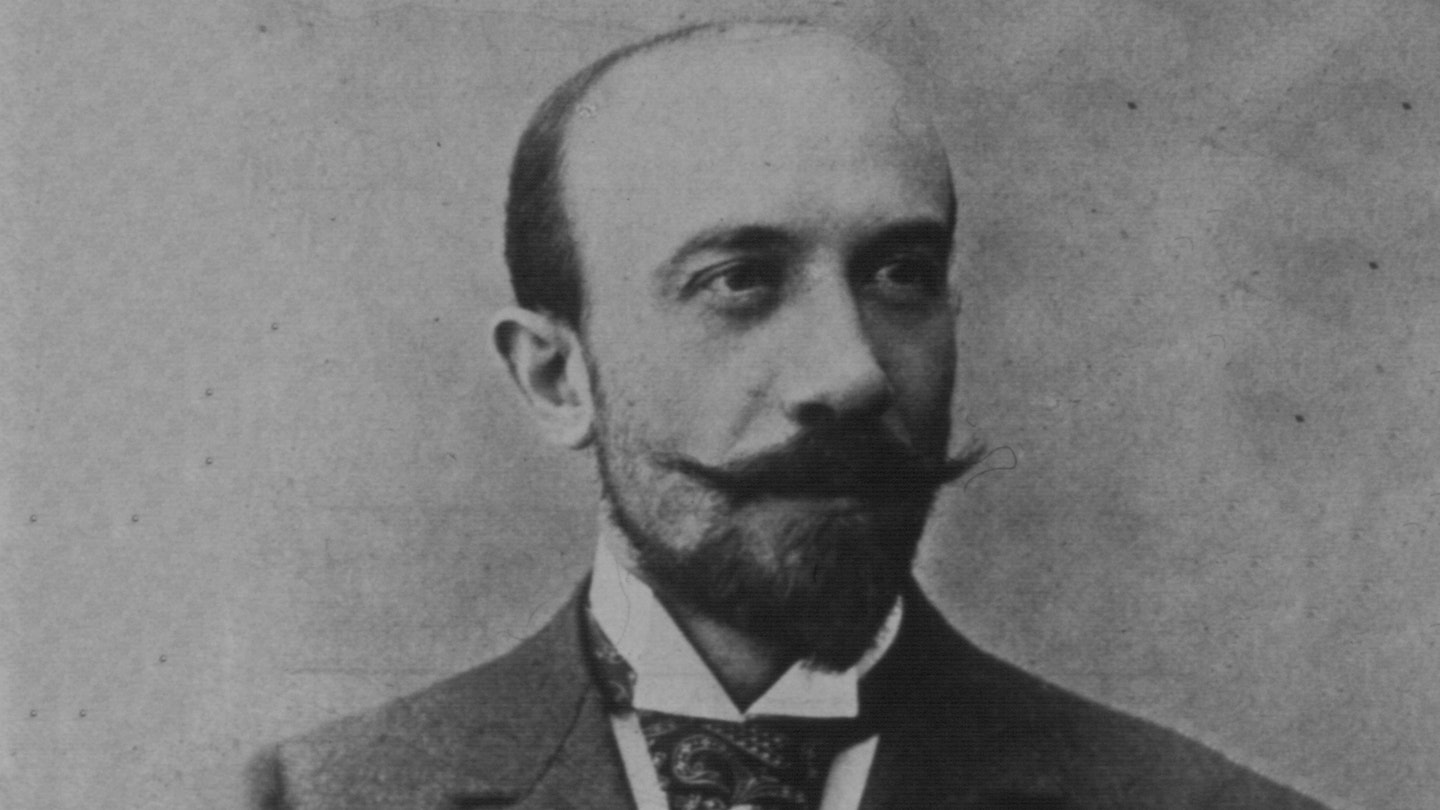

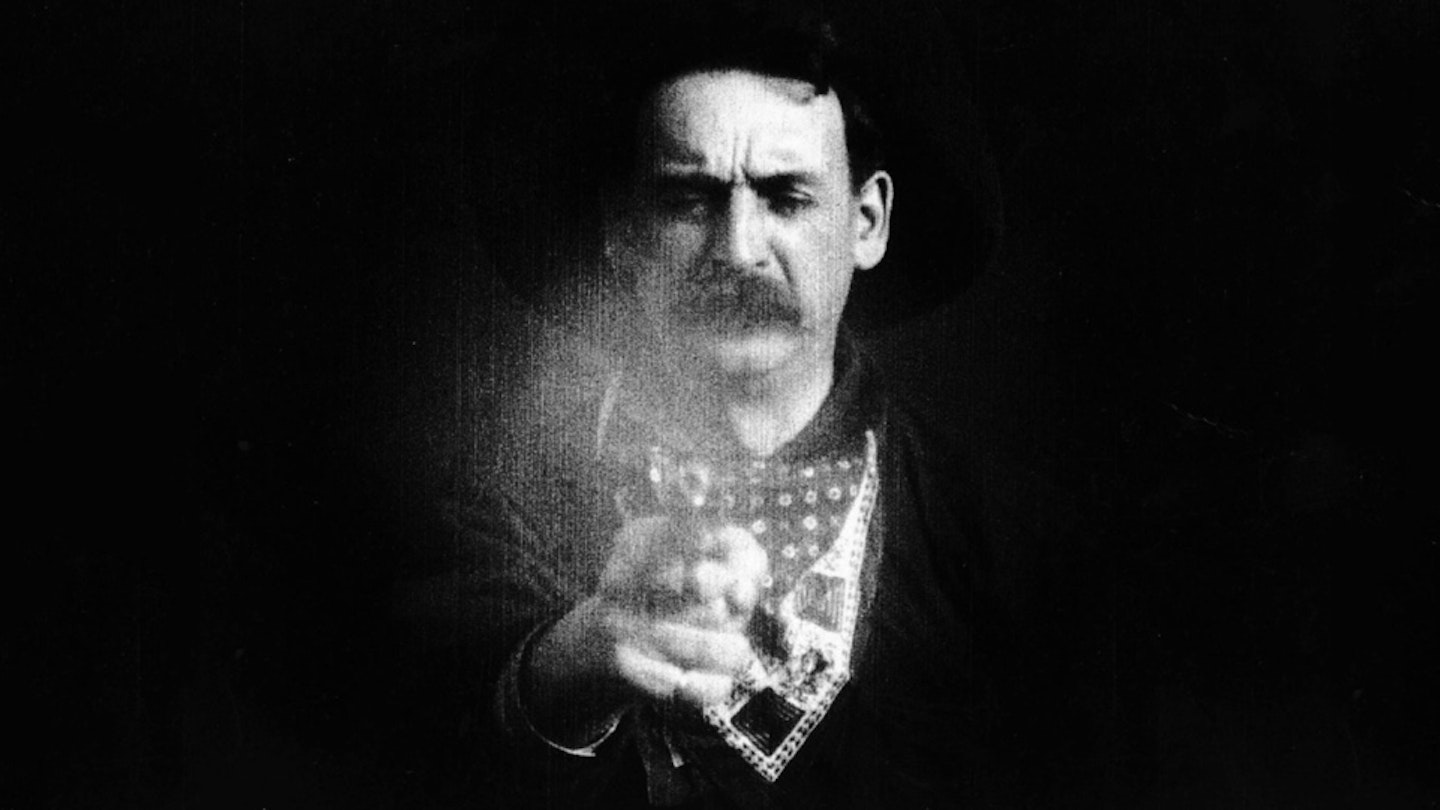

G is for Georges Méliès

Aside from inspiring everyone from Martin Scorsese to The Mighty Boosh, magic man Georges Méliès was the joker in early cinema's pack. A showman and theatre actor who was happiest when he was making things disappear and then reappear with a rabbit on their heads, stumbled on the film medium's potential for trickery when his patented Kinétograph camera malfunctioned while filming a street scene in Paris. "It took a minute to get the camera going again", he'd later remember. "During this minute the people, buses and vehicles had of course moved. Projecting the film, I suddenly saw an omnibus change into a hearse and men into women." Aside from making an early version of Tootsie, Méliès had unwittingly invented special effects - the sleight of hand that would power cinema's creative Allspark. His lunar adventure Trip To The Moon, depicting France's space programme circa 1902 and its encounter with surprisingly fragile xenomorphs the Selenites, employed his new techniques to presto top-hatted astronauts into space and back. Regardless of whether you view it as narrative storytelling or gimmickery as some Méliès critics have suggested, it's a landmark in sci-fi cinema.

H is for Hugeness

Movieland strode boldly into its first era of giganticism in the 1910s. Filmmakers like D. W. Griffith and Giovanni Pastrone, the James Camerons and Ridley Scotts of the 1910s, corralled unwieldy visions onto the screen. It was an time when, if people talked about "the elephant in the room", they were usually referring to an actual elephant - and often more than one. The sets of Pastrone's Cabiria and Griffith's Intolerance resembled small cities peppered with mini zoos, with leopards and monkeys prepping for their scenes, and the directors busying themselves with complex new camera moves. One, a slow zoom on Ancient Babylon in Intolerance, was initially planned for a platform on a hot balloon until physics and the threat of fiery death intervened. The film had 16,000 extras and required $2m of Griffith's own funds - and bear in mind this was all 50 years before the invention of Valium. Griffith regularly acknowledged his debt to Pastrone - Cabiria, which lent its name to Fellini's Nights Of Cabiria, comfortably stands up - but it's Birth Of A Nation and Intolerance that did most to create the blueprint for the modern blockbuster.

I is for Intertitles

The story of the intertitle (or title card) kicked off with R.W. Paul's short Scrooge, Or, Marley's Ghost in 1901. It became silent cinema's main means of communicating dialogue and imparting exposition to audiences, but could also deliver its own emotional punch in upper-case nickelodeon as with the final card of Chaplin's City Lights ("Yes, I can see now") or Murnau's Nosferatu ("The ship of death had a new captain"). There was even an Oscar for the art at the first ever Academy Awards in 1929, although no record was kept of how the heck that speech was delivered. The advent of the talkies meant that, with the odd exception like Michel Hazanivicius's The Artist, intertitles would soon disappear like one of Murnau's famous Sunrise dissolves.

J is for Jacques Pathé

If the word 'Pathé' makes you think of grainy old newsreel footage or that famous rooster crowing out a giant logo bubble, bear in mind the Pathé clan, Charles (the driving force), Émile, Théophile and Jacques, played an integral role in arming the newbie filmmakers with the equipment to get their motion pictures in the can. Starting out in the gramophone business, the brothers set up Pathé - 'Compagnie Générale Des établissements Pathé Frères Phonographes & Cinématographes' if you're not into the whole brevity thing - to meet demand for cameras and film stock. By the outbreak of World War I they'd sown up the European market, expanded into America and built more than 200 cinemas around the world. The company survived the painful transition to talkies - just - and went on to flourish. Pathé now owns 300 cinemas, a production company, a newspaper and part of Olympique Lyonnais. Which, as roosters go, rather puts Foghorn Leghorn to shame.

K is for Kinetoscope

If you grew up staring in wonderment at dinosaurs on a 3D View-Master, you'll have an idea of how people might have felt gazing at the spinning images inside Thomas Edison and W. K. L. Dickson's Kinetoscope in 1891. The viewer and it's twin sister, the Kinetograph camera, ran on George Eastman's 18mm celluloid. In his authorative tome From Peepshow to Palace: The Birth of American Film critic David Robinson describes the way the film "ran horizontally between two spools, at continuous speed. A rapidly moving shutter gave intermittent exposures when the apparatus was used as a camera, and intermittent glimpses of the positive print when it was used as a viewer, when the spectator looked through the same aperture that housed the camera lens." Or, to put in layman's terms: "OMG. IT'S A FRICKIN' MOVIE!"

L is for Lyon

A sprawling metropolis in France's south east - think Birmingham with nicer cheese - Lyon can justly claim to be if not the birthplace of cinema, then at least one of its maternity wards. Thanks to Louis and Antoine Lumière, the earliest of cinema's great sibling teams, it played host to the first ever film set. Alas Workers Leaving The Lumière Factory In Lyon, a 46-second documentary shot at their dad's photographic plant, didn't spawn a sequel called Workers Get Home And Switch On MasterChef, but when it was shown to a private audience in March 1895 it was greeted with agogery. The pair's natural flair for technical doohickery, sparked by an encounter with Thomas Edison's Kinetograph, had been channelled into the more portable Cinématographe shooting 16 frames per second. Their device, a commercially successful camera/projector, made its public debut with a ten-film showcase at Paris's Grand Café on December 28, 1895 (see 'A') that included that factory-set flick. If you're ever in Lyon, head to the Institut Lumière and see it in the place it was shot.

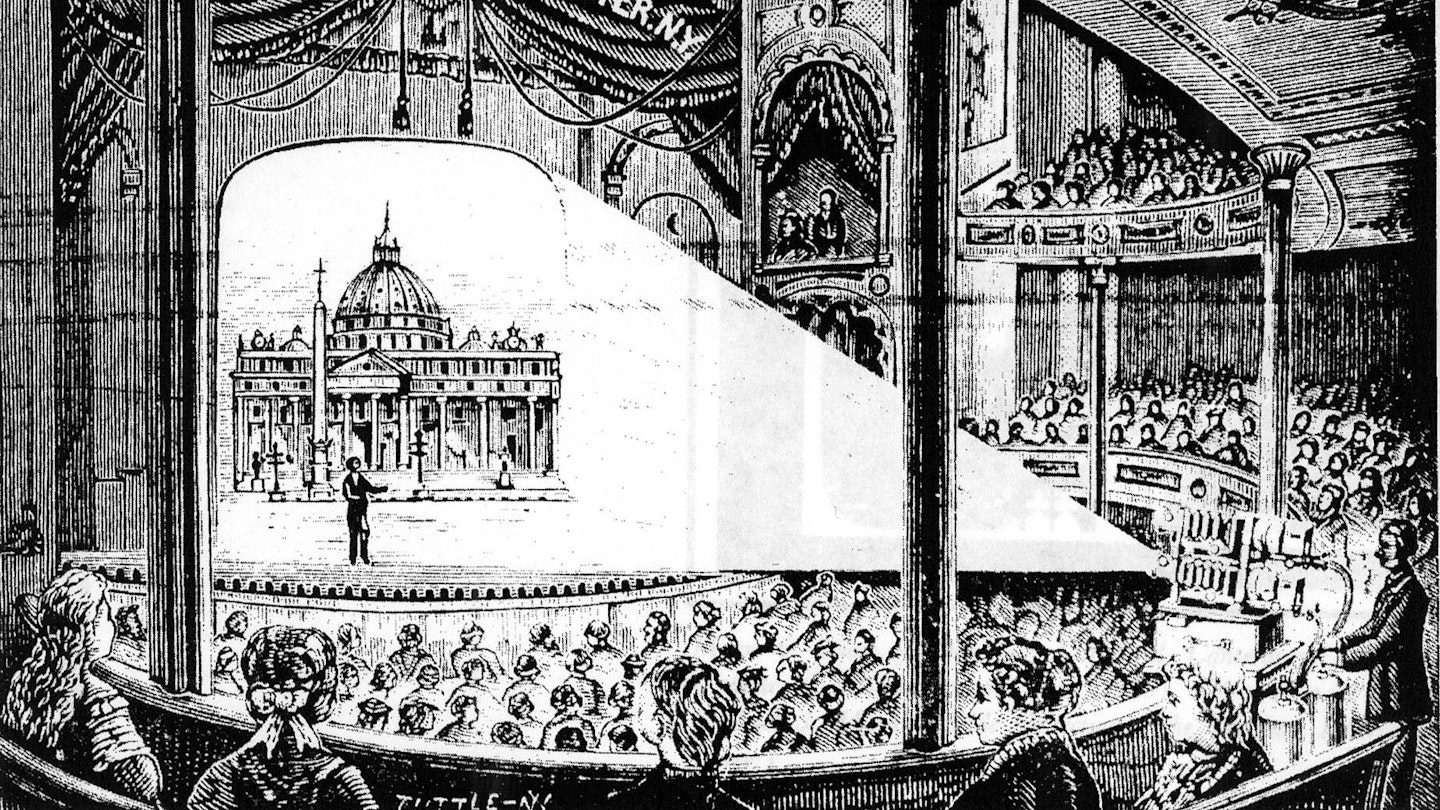

M is for Magic Lantern

The first form of recorded entertainment, the magic lantern, or 'Laterna Magica' to give it its Harry Potter name, dated back to the 17th century and possibly earlier. There are tales of ancient Chinese contraptions that used painted glass and a naked flame to create a flickering image. By the early 19th century, this device, a veritable box of visual tricks, had entered the mainstream. There were tens of thousands of magic lantern showmen criss-crossing America, blowing people's minds with images of wonders educational, comic, adventuresome and, occasionally, ahem, exotic. Particularly prolific was Joseph Boggs Beale, a Philadelphia artist who turned out 2000 drawings between 1881 and 1915. These included A Drunkard's Reform, a Ken Loach-y salutary tale about the perils of the devil booze, and a frame-by-frame gallivant through the life of Abe Lincoln that was Spielbergian in its scope. Méliès, Muybridge and company were all alerted to the potential of the flickering image.

N is for Nickelodeons

"It is not too much to say that modern cinema began with the nickelodeon," film boffin Charles Musser wrote of early cinema's answer to the multiplex. These were often built into city storefronts, were cramped and dark, and showed short films, illustrated tunes and the odd feature-length affair to rapt audiences. The name, which combined the cost of admission (5c) with the name of a famous Parisian theatre, had been around for a long time before Spongebob Squarepants and co appropriated the name, but was most frequently on the lips of the public between 1905 and 1915. This was the decade when moviegoing first became a staple part of the public's to-do list, so if left your house to see Identity Thief you can blame the nearest Edwardian.

O is for Operatic

Long before the Zimmer brrrraaahm or even the swell of an Alfred Newman symphony, silent films were usually scored by a pianist desperately trying to drown out the whirl and crank of the projector. Classical musical - often Tchaikovsky's Pathetique Symphony or Rossini's William Tell Overture - was used as the accompaniment to any action sequences, although Georges Méliès liked to play along to his own films. The first ever film score was by French composer Camille Saint-Saëns' piece for The Assassination Of The Duke Of Guise in 1908, swiftly followed by Joseph Carl Breil's ditties on Queen Elizabeth in 1912. Head to our Birth of the Soundtrack piece for the full lowdown on the burgeoning art of the film score.

P is for Pigeons

In 1827, boffins Claude and Nicéphore Niépce, a pair of brothers from Saint-Loup-de-Varennes in eastern France, took the first reported photo using coated tin plates. After eight hours' exposure, View From The Window At Le Gras emerged, preserving the neighbouring pigeon house for posterity.

Q is for Queen Elizabeth

Queen Bess, the Virgin Queen, the Big E... whatever you call her, Elizabeth I has been a movie and TV staple played by actresses from Cate Blanchett and Helen Mirren to Glenda Jackson and Miranda Richardson. But first to don the red wig was Sarah Bernhardt who played the monarch in a 53-minute depiction of her romance with the Earl of Essex. Shot in Paris and completed with cash from movie mogul Adolph Zuckor (see 'Z'), Queen Elizabeth made its US bow on July 12, 1912 in New York becoming the first ever feature-length film to play in America. With a specially-penned score by Joseph Carl Breil, later D. W. Griffith's composer of choice, it was also the feature-length movie to boast an original soundtrack. It's stiffness and theatrically hasn't helped it stand the ravages of time and changing tastes - "pretty crummy" is one of the more generous Amazon comments - but its place in early film history is undeniable.

R is for Regicide

Early filmmakers loved the 16th century, and who can blame them with its courtly intrigue, spicy happenings and ginormous ruffs. The fall guy in 1908 period piece The Assassination Of The Duke Of Guise - the Duke, yo - is the dramatic heart of the 15-minute flick that contained only nine frontally staged shots, some minor roister-doystering and a big old swordfight. Far more significant than its content or the filmmaking techniques employed by directors Charles Le Bargy and André Calmettes is its role as the first release of France's Film d'Art, a studio set up to keep commercial and artistic aims in harmony with a Clooneyesque care that would breed films like Abel Gance's Napoleon and even, later, the work of Claude Chabrol.

S is for Stars

Silent cinema gave rise to some huge stars. There was Greta Garbo who famously would talk and Buster Keaton who wouldn't. There was Valentino to bewitch audiences with his mystique and Chaplin to make them laugh with his little tramp. There was Fairbanks, Gish and Brooks, and Harry Lloyd to rival Keaton as king of the catastrophic pratfall. But first among equals for a time, a glittering celebrity with enough razzle to power an army of Baz Luhrmanns, was Sarah Bernhardt. The Parisian has been dubbed "the most famous actress the world has ever known", thanks partly to a press-friendly persona, nose for decadence and general aura of genius gone slightly to seed. Her fame as a stage actress translated to big-screen billings that carrying the new medium further into the public consciousness. Convention was damned regularly during her career, not least when she played Hamlet in an adaptation that snuck in at just under 242 minutes shorter than the Kenneth Branagh version. Her IMDb page boasts only eight features, including Queen Elizabeth in 1912 (see 'Q'), the proceeds of which helped Adolph Zukor (see 'Z' below) found Paramount Pictures.

T is for Thomas Edison

Lightbulb-brained genius Thomas Edison may be best remembered as the person who helped us see things when it gets dark, but he was also a key player in cinema history, albeit from a technical rather than creative standpoint. Not only was he responsible for building the world's first for-purpose film studio, the Black Maria, in New Jersey in 1893, he also channelled the principles of Eadweard Muybridge's moving picture invention, the Zoopraxiscope, into his own version, the Kinetoscope. The legendary inventor never saw an device he didn't want to patent - 1093 in total - or a competitor he didn't want to litigate against - although the Kinetoscope, his most important invention, slipped through the net. The device's design was chanelled, legally, into continental doppelgangers like the Lumières' Cinématographe, which infuriated Edison, although it could be argued that he himself had been standing on the shoulders of giants.

U is for Undressing

Approximately 20 minutes after film was born someone invented the blue movie, kicking off a surrepticious parallel film industry and setting the humble German plumber on the path to sex god status. That someone may well have been still photographer Eugène Pirou - yes, porn was invented by a Frenchman - whose 1896 seven-minute stag film Le Coucher De La Mariée (Bedtime For The Bride) had stage performer Louise Willy showing a lot more than just ankle. Even notables like Charles Pathé and Georges Méliès (Méliès' wife would appear in as a maid in an 1897 skin flick) were soon muscling in with striptease flicks of their own, although censorship would put pay to that in 1911. A 1910 German film called Am Abend - yes, hardcore was invented by a German - introduced specialist audiences to things we can't even describe here for fear our mum might read this.

V is for Virtuosos

The Lumière brothers, Muybridge, Méliès and Edison are early cinema's blue plaque names but there were a clutch of other inventors and pioneers worthy of an Oscar-night showreel. Hatton Garden's own R. W. Paul (the camera dolly) and American Billy Bitzer (lighting and camera techniques) are worthy of special mention - Intolerance's grandeur owes plenty to Bitzer's raw ambition - while G. A. Smith (colour film process), Étienne-Jules Marey (multi-exposure photographic gun) and Cecil Hepworth (first commercial Brit flick) joined them at the vanguard of the new form. Others like Birt Acres, who, with Incident At Clovelly Cottage, made the first ever British film, and American inventor Jean LeRoy could also claim a nook in film history.

W is for Westerns

If Trip To The Moon was the first ever sci-fi, The Great Train Robbery was the first notable Western and the first narrative film all rolled up in 12 pistol-packing minutes. Its director, Edwin S. Porter, built on the storytelling techniques he'd employed earlier in that year on The Life Of An American Fireman, including crosscutting and slick camera work, to a story of a violent gang of outlaws on the take. Groundbreaking in many way, it had a location shoot - in New Jersey's South Mountain Reservation - a final act shootout in which - spoiler! - all the baddies get wasted, and even broke the fourth wall when one of its armed bandits aimed pointedly into the camera and pulled the trigger. Martin Scorsese famously referenced that final shot in GoodFellas, and Ridley Scott did likewise in American Gangster.

X is for Max Linder (kind of)

The comic who inspired Charlie Chaplin, and by default everyone from Jacques Tati to Rowan Atkinson, came from unlikely stock. Max Linder's devout parents owned a vineyard and his brother played rugby for France but his first love was the theatre, making him one of the first recorded men to disappoint his dad by wanting to become an actor. Migrating to the movies, he briefly crossed paths with fellow pioneer Georges Méliès, appearing in 1905 short The Legend Of Punching, but it was his mustachioed scallywag Max who made his name. The well-to-do gadabout with an eye for the ladies got into all manner of saucy scraps over 100-plus shorts, like this one, Max Takes A Picture. He died in 1925, stricken with depression, but Chaplin, who once gave him a photo signed "To Max, the professor, from his disciple Charles Chaplin", didn't forget him. Neither did Quentin Tarantino, whose Inglourious Basterds namechecked him.

Y is for Yorkshire

You know what we were saying about the Lumière brothers first publically premiering cinema? Well, Louis Le Prince and the people of Leeds might argue. The Frenchman ex-pat's Roundhay Garden Scene, a buccolic affair shot in Leeds' Shot at 12 frames per second and lasting a full 2.11 seconds (there were no deleted scenes), was filmed in 1888, a full seven years before the brothers worked it out. The film though raises more questions than answers - and we're not referring to the extraordinary hat on that lady's head. Filmed in the gardens of Joseph and Sarah Whitley, Le Prince's in-laws, using Eastman Kodak film and a single lens camera-projector, Le Prince's film is likely to be the oldest film in existent. That his name, in contrast to Edison or the Lumières, is more widely known owes much to his mysterious disappearance on September, 16 1890 in America. Was Edison, hungry to copyright the movie camera, behind it?

Z is for Zukor

When Paramount put out the bald statement that its founder Adolph Zukor had "taken a nap and died at 4 o'clock in the afternoon" on June 10, 1976, Hollywood began mourning one of its founding fathers. Zukor was born in Hungary, made his way to America, earned some money in the fur business before spotting the potential in penny arcades and nickelodeons and bringing his business philosophy, "look ahead a little and gamble a lot", to bear on the brave new world of movies. He wasn't bullishly charismatic like fellow mogul Samuel Goldwyn and Louis B. Mayer, and shrugged off praise for his creative genius, but he could spot star quality (he gave Sarah Bernhardt her shot at film immortality), could negotiate with tough operators like Thomas Edison, established a model for film distribution and most importantly, saw the river of green ahead. Typically, the one-time boy wonder would look back on his achievements with modesty. "I wanted to be a merchant when I was a boy", he recalled, "and that is what I am now and always have been - a merchant."