As The Fellowship Of The Ring turns 20 years old – and moves to the top spot in our newly updated list of the 100 Greatest Movies Of All Time – there’s never been a better time to whisk yourself away to Middle-earth once more. Whether you’ve started your Lord Of The Rings rewatch or not – maybe you’re still arguing between doing the theatrical or extended editions – take a look back at the making of the first film in Peter Jackson's epic trilogy with the original Empire feature.

All that time ago, we went on set in New Zealand, speaking to Jackson and the majority of the cast about bringing cinema’s most epic fantasy saga to life – from the casting process to the mammoth (or, Oliphaunt) shoot. Read the full feature here, first published in Issue #151.

Framed by a gigantic stone troll and the spherical, wooden door of a Hobbit hole, Peter Jackson shrugs with the amiable air of a man immune to the forces of hype and begins with a shocker: “You know, I never really harboured an ambition to make Lord Of The Rings…”

Empire and this most affable of directors are currently basking in the Cannes sunshine, where most of the cast have joined their boss for the film’s launch party (hence the extraordinary props in mid-shot). From this delightful spot our tale will venture to the wilds of Middle-earth, its earthly surrogate, New Zealand, and a sleepy suburb of Oxford. But, for the moment, let’s take a brief detour to Kazakhstan.

In this strict corner of the former Soviet Union, there has been a recent crackdown on so-called “Tolkienists”. Thousands of Kazak fans, it seems, have been dressing up as Hobbits and re-enacting pivotal moments from the Godfather of fantasy fiction (very popular since perestroika granted its first translation in 1988). However, the local authorities take an extremely dim view of such “bohemian lifestyles”, accusing the wannabe Bilbos of “being Satanists and conducting dark rituals”. Regular “meets” are typically met with the iron boot of discipline.

Dark times, indeed, in deepest Asia, but it goes to show. With 100 million near-pathological readers, this story of a ring, a heroic shortarse and an imminent apocalypse has become a global brand to rival Coca-Cola or Microsoft. Indeed, Tolkien’s magic so pervades the universes of Star Wars and Harry Potter, lawsuits should have long since dropped on respective gilt-edged doorsteps. Lord Of The Rings is big business, but wasn’t it meant to be unfilmmable?

“Tolkien’s writing is so vivid you can imagine a movie, you can imagine the camera angles, and the cutting. You can just sort of see it playing itself out.” – Peter Jackson

During post-production on The Frighteners in 1995, Jackson was mulling over the possibilities of this new computerised technology. His own special effects company, Weta (named after a Kiwi bug), were completing the elaborate CGI on the movie and he mused how easily these malleable pixels could lend themselves to a movie like his hero, Ray Harryhausen, used to make. With his proposed remake of King Kong about to falter in pre-production, he thought he could really go for a Lord Of The Rings-type movie. Hold on a minute, what about Lord Of The Rings?

“I read the book once when I was 18,” begins Jackson, inspired to pick up the tome after watching Ralph Bakshi’s animated version in 1979. “I thought, ‘No-one’s made a live-action version.’ The key is that ultimately you cannot make one film of it, you have to lose too much material. You couldn’t call the movie Lord Of The Rings with an honest face.”

With the idea of making two movies, he set about discovering who owned the rights. This alone would take a year. All the while, Jackson refused to pick up the novel again for fear his project would be drowned in legal soup. Tolkien, it transpired, had sold the rights to MGM at the end of the ’60s. After a couple of abortive attempts and the author’s death, producer Saul Zaentz, a canny broker who won an Oscar for The English Patient, bought out MGM and did nothing. Okay, he produced Bakshi’s ill-fated ’toon, but he, like the world, became convinced it could never happen. He hadn’t counted on Jackson’s creative vision. “Only because of him, I gave away the rights,” Zaentz gushed.

They took the deal to Miramax who, half-heartedly, offered to stump up for one film. With limbo threatening, Jackson turned to Bob Shaye at New Line. Shaye, a passionate fan of both the Kiwi director and the late Oxford don, flatly refused to make two films. He would do it only if they made three. Giving him $270 million ($90 million a film) and total creative freedom to do so. The deal done, Jackson picked up the book and began to read.

“We were sitting there talking and drinking beer, and someone said, ‘Oh, look who walked in.’ It was Professor Tolkien, and I nearly fell off my chair." – Christopher Lee

Christopher Lee, who gives twisted wizard Saruman the full weight of his basso menace, was unique among the cast and crew that would sprawl over the luscious islands of New Zealand. He was the only person who had actually met Tolkien. Forty-five years previously, he had gathered with some friends in Oxford, who decided to head out to The Eagle And Child (famously Tolkien’s local). And in he walked.

“I didn’t even know he was alive,” Lee recounts with the verve of a man who has dined out on the anecdote for the last two years. “He was a benign-looking man, smoking a pipe, an English countryman with earth under his feet. He was a genius, a man of incredible intellectual knowledge. And he knew somebody in our group. My friend said, ‘Oh, professor, professor,’ and he came over. Each one of us, I knelt of course, said, ‘How do you do?’ and I just said, ‘How… Ho… Ho.’ I just couldn’t believe it. I’ll never forget it.”

Born in Bloemfontein, South Africa, in 1892, Professor John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was a personable, private man, partial to a pipe of tobacco and a pint. A veteran of the trenches of World War I, he lived in Oxford, head of English at Merton College. More as a pastime than with any great urge to be published, Tolkien spent his downtime creating a massive mythology whose scope and detail rivalled the great Norse and Germanic odes he adored. Then one day, he took a clean leaf of paper and wrote, “In a hole in the ground there lived a Hobbit.”

The Hobbit and its grown-up brother, The Lord Of The Rings (1954), would become a publishing phenomenon such that 46 years later, much to the consternation of cabals of literary fascists, his grand opera of the quest to destroy an evil ring was voted the 20th century’s favourite book. Tolkien spent much of his later life dodging the adoring masses, infuriated by his loss of privacy, protective ’til the last of his world of Hobbits. Yet he was never opposed to the idea of a film. When an animated version was pitched to him in 1957 he was, initially, agreeable, but strictly guarded the sanctity of his prose. “I am quite prepared to play ball,” he wrote to his publisher, “if they are open to advice.” The ghost of J.R.R. would be keeping a watchful eye.

“The most difficult thing has been the script. Without any doubt, the scriptwriting has been a total nightmare.” – Peter Jackson

Tolkien’s magnificent epic runs (depending on edition) to 1,008 pages (not including maps, introduction, prologue and appendices). It’s a big book, a whopper. Embarking upon a read is to enter a long-term relationship with pages teeming with myriad detail and imagination without equal. It also serves as an excellent doorstop. And while three films, running from two to three hours a piece, is very generous, things were going to have to go. Here, of course, lay potential quicksand; the danger of aggravating those millions of disciples for whom the mythos is nothing less than a religion.

“It was very organic,” says Jackson of the process. “We had an important responsibility — it has to be a good night out. Then you have a responsibility to Tolkien and protecting the work. Somehow you have got to make the two of them merge. The concept of a faithful adaptation is such a nebulous thing, our adaptation can’t be faithful. You can’t just take the book and go and shoot it.”

Jackson did not embark on the task alone. His wife Fran Walsh — a collaborator on all his films — and friend and playwright Philippa Boyens formed the fateful troika who would set about the impossible.

“I like to think of it, and the choices we made,” Boyens opines of the cuts, “that we chose to leave some things untold, rather than left out. Unsaid.” It wasn’t just trimming, though; the plot needed massaging for the screen. For starters, the book is very boyish, the female characters are marginal at best, while the singular love story — betwixt Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen) and Arwen (Liv Tyler) — is relegated to the appendices. Solution: whip it back out again, thread it in and give Tyler something to get her chops into.

“For me as a girl and that kind of girl,” says Tyler, “one of the main things that attracted me was the power and beauty of the love story. It is the most dreamy, classic kind of love story — classic struggles and decisions.” The point is, Aragorn, a man, is mortal, and his beloved Arwen is an Elf and therefore immortal. To stand by her man she has to give up on eternity. In Tolkien’s turbulent universe, happiness comes with a price.

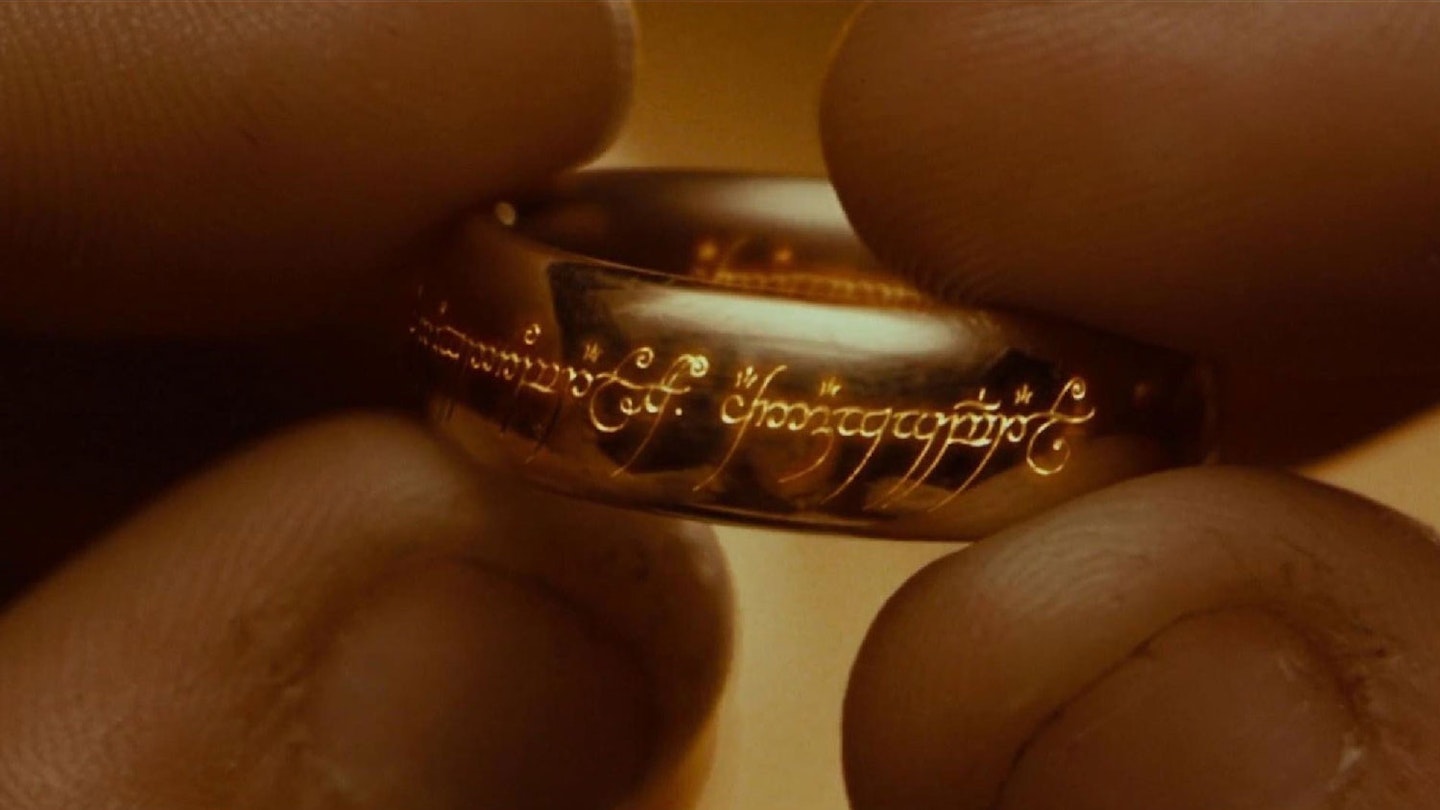

An even trickier problem was the lack of a meaty bad guy. There are bad guys per se, just not very visible ones. Sauron, the Dark Lord, the main mother, is manifest as a giant, red eyeball who never leaves his hideous fortress, Barad-dûr — his malign influence more pervasive than physical, cinematically a no-no. Saruman (Lee) is a corrupted wizard who really throws a wand in the works, but he too is fairly static, never leaving his evil sanctuary of Orthanc. Not to forget the reams of twisted minions — Orcs, Black Riders, Balrogs — but, in Hollywood terms, there was no supercharged villain. Their solution was ingenious. “We made the Ring a character,” explains Jackson. “It speaks, it sings, it calls. When we were filming the Ring we always shot really close, filling the entire screen, to give it kind of a presence.”

Then they got really ambitious. Try Dances With Elves — the pointy-eared ones will converse in their own sing-song lingo, a patter Tolkien invented. So, Elves-to-be, Liv Tyler, Cate Blanchett (as imperious Lady Galadriel) and Orlando Bloom (as Legolas) were going to have to go to Elf School. “You should hear Liv speak Elvish, it’s remarkable,” enthuses Jackson. “She has a beautiful voice, the language is fantastic. Ask her to do some.”

It seems everybody in Cannes has asked Tyler to “do some Elvish”. She wearily pulls her shoulders back and raises her head, assuming the requisite ethereal grace (according to Tolkien the Elves are swan-like angels who are really good at everything), and whips out an extraordinary line of dialogue. Bits of Scandinavian, French, even Welsh seem to spill over themselves. She might be singing. Steve Tyler’s daughter has become an Elf.

“His casting is impeccable. I have never walked into a first reading of anything before and looked around and identified all the characters: ‘That’s got to be Frodo… That’s got to be Legolas the Elf... That’s got to be Sam.” – John Rhys-Davies

The very moment the movie was made public, we all knew it was going to be Sean Connery to play Gandalf, the aged wizard typified by his waist-length beard and pointy hat. That was a given. Except it wasn’t. Jackson was running his own show and had one simple proviso in casting: “There was no agenda to cast actors for any reason other than to find the best people for the role.” It seems Sean Connery — while certainly on Jackson’s to-work-with list — was just too Sean Connery to don the beard. Instead they chose Sir Ian McKellen; add one stick-on face rug and grey cloak, and the wizard was alive. “I didn’t know where Ian McKellen began and Gandalf finished,” marvels Jackson. “He just gets absorbed in the role.”

They soon hit a snag, though. They couldn’t find hero and Ringbearer, Frodo. The original idea was that all the Hobbits would be played by Brits; after all, Tolkien had imagined the denizens of the idyllic Shire as diminutive Englishmen. Over 150 young British actors were auditioned, a process that delivered up Dominic Monaghan (as Hobbit Merry), Scottish actor Billy Boyd (as Hobbit Pippin) and Kent-born Orlando Bloom. But no Frodo.

“You knew within two minutes whether they were right or not,” says Jackson. “And Frodo hadn’t walked in the door.”

Then a package arrived from Los Angeles. One Elijah Wood had got wind of the project and taken some pages, rummaged up some makeshift Hobbit garb and headed for some nearby greenery to videotape his own ‘audition’. “We were at a desperate point in trying to find Frodo and we put this tape in the machine and it was extraordinary. There he was.”

Once the non-American rule had been dispensed with, Samwise — Frodo’s indomitable sidekick — was soon filled by Sean Astin. The other pivotal role is that of Aragorn, the heroic, rugged, king-to-be. The answer: 28 year-old Irish actor, Stuart Townsend. Right? Err, wrong. The second major hitch arose two weeks into shooting when Townsend was dumped. “Stuart is a huge Tolkien fan,” admits Jackson, honest enough to acknowledge his own mistake. “He said to us, ‘You’re crazy, I’m too young. Aragorn should be a rugged man in his 40s.’ We came to realise this wasn’t the character in the book.” Townsend is less magnanimous about the situation, describing, to the Los Angeles Times, his brief sojourn in Middle-earth as “a nasty nightmare”.

Enter Viggo Mortensen. “I’m a great believer in fate,” the director philosophises, “and fate can either be kind to you or not kind. I do believe there are forces at work. And the moment Viggo became part of this project was marvellous. I’ve never seen a guy became a character more than Viggo; he became Aragorn.”

The principal cast was rounded out by Sheffield stalwart Sean Bean as Boromir, the most complex member of the team (“He is much more susceptible to the powers of the Ring, something he is fighting like an addiction throughout the journey,” says Bean). And the splendid John Rhys-Davies, a barrel-chested thesp with the mightiest voice in Christendom, who plays Gimli, an outspoken Dwarf. Peter Jackson had formed his Fellowship.

“Where do you begin with Pete Jackson? He is a complete enigma. There are elements about him which mean he shouldn’t be a director. He’s just too nice, he’s too much of a family man.” – Dominic Monaghan

Peter Jackson, upon whose broad back this entire, unfathomable enterprise has rested for over five years, owns one pair of shoes and two shirts of identical colour and design.

He wears knee-length shorts no matter what the elements choose to hurl at him. Indeed, the cast members assembled for the Cannes shindig are stunned to see the squat Kiwi actually wearing long trousers.

“He has nothing to do with fashion,” explains McKellen, implying this is the very height of flattery. “The world we live in has a lot to do with fashion. His has to do with basics, getting on with making something work, making something happen. He’s very practical and that’s very reassuring. He was always relaxed. And looked like a Hobbit.”

That Jackson is possessed with Hobbit-like qualities is something on which the entire cast concur. That and the fact that he seems to be some fizzing amalgam of savant, father-figure, genius, husband, warrior and clown. “He’s as cool as an Elf, he’s got the heart of a Hobbit and is as mad as a Wizard,” chimes Bloom with the neat syncopation of the sturdy soundbite. “I mean all these characters are within him. It was his baby, his labour of love.”

Throughout 18 months of a gruelling schedule, Jackson never once lost his cool. He welcomed the thoughts of his cast, but always seemed to have the right answer to every dilemma. Before every shot, no matter how small, he would read the appropriate section from the book to make sure the spirit of Tolkien was there to keep it real. “If he ever said anything twice it was done,” asserts Wood.

Living barely seven minutes away from his own Three Foot Six Studios in Wellington, with two kids and two dogs, Jackson would seem an unlikely choice for this long-awaited adaptation. Born on Halloween in 1961, he began filmmaking at the age of eight, making Super-8 shorts. At heart he was a horror practitioner, splurging the screen with equal servings of comedy and viscera. Bad Taste (1987), Meet The Feebles (1989) and Braindead (1992) speak of a subversive sicko yet a lightness of touch. Heavenly Creatures (1994), which invented Kate Winslet, indicated more was going on; this elaborate, true-life story of matricide revealed a gift with actors and a sweet eye. The Frighteners (1996), a horror-comedy with Michael J. Fox, may have flopped, but its silky computer effects and Gothic style (the hooded reaper is a dead ringer for the Dark Riders) gave the strongest hint that he could be the guy to breathe life into Tolkien’s opus. What does emerge is the entire lack of compromise: all of his films are made in New Zealand, all with his own special effects company, all without the infuriating gaze of Hollywood. Still, for the fans of his gooey, outlandish oeuvre, there is a concern he’s sold out.

“I absolutely want to do Bad Taste 2,” he counters. “I want to go back and do a splatter movie. I’m still that person.” The scale, though, had grown significantly.

“We always had two units shooting and we had miniature units as well. Another two units made four and occasionally we had a scenic unit going out filming boats on the river, or doubles up snowy landscapes.” – Peter Jackson

Take a glance at the stats involved and the enormity is staggering:

The film schedule was 274 days over 15 months, from October 1999 to December 2000. They used 21 cameras, 5 studios and 4.5 million feet of film. There were 350 different sets, some as large as city blocks. A total of 330 vehicles were used, stretching 1 km when parked bumper to bumper. The crew grew to 2,000, with 22 major roles. 30 km of roads were built for the film. At one meal, 1,440 eggs and 160kg of meat were consumed. 48,000 different props and miscellaneous items were created.

Whichever way you look at it, it was one of the most awesome shoots ever mounted — three movies shot simultaneously out of sequence, a process as exacting as it was fulfilling.

As the shoot wore on and the pressure mounted, Jackson could be seen cycling from set to set at the Wellington studio on an old bicycle, eager to save time. Bloom remembers one miraculous day when he traversed the whole country by helicopter to get to his next shot, complete with stick on ears and blonde wig. Promised breaks came and went, six-day weeks of 14 to 15-hour days became the norm. And somehow throughout it all, spinning every plate, Jackson just kept going.

“I’m totally unfit, but I’m the tortoise guy who can keep plodding on. Mentally I had days when my brain would feel like it was mush, I felt I had no imagination left. When your imagination starts to lock, you panic. Honestly, there were days when I was just turning to the actors and hoping they weren’t as tired as I was and pointing the camera at them, hoping we were getting good stuff.”

The cast, too, felt the pressure, sick of sticking on their Hobbit feet, sick of the outdoors, just completely knackered. Working together under such extremes, in an elemental, beautiful environment like New Zealand, combined with the spiritual rub-off of a storyline about a group of disparate personalities uniting for a common cause, was bound to bring them close. But these were friendships cast in stone. “Because of the length of time, the unceasing grind of it,” says Mortensen, “we came to know each other’s good and bad points. You became entangled in each other’s lives in a good way. I felt that I became part of them and they became part of me.”

The Hobbits in particular became their own band of brothers. When not shooting they learned to surf together, they took trips to Thailand and Australia, they went skiing, snowboarding, white water rafting and bungee jumping. They referred to themselves as Hobbits. “We became friends for life,” says Sean Astin, who had his family with him for the duration. “They were like uncles to my daughter. Art imitated life or life imitated art, or something.”

Consequently, away from the camera, much hilarity was to be had. Bean (a devout Sheffield United fan) would find himself frequently nutmegged by Monaghan (a devout Manchester United fan) during on-set soccer tournaments. The pair even enticed Mortensen back to the 20th century to watch England vs. Germany in Euro 2000, via satellite. Monaghan returned one afternoon to find his trailer sealed up with police tape, care of Mortensen. He returned the favour by smothering the front of Aragorn’s trailer in shaving foam and tracing the words, “false king!”.

“We would do this thing that if the Fellowship had to do a scene,” laughs Monaghan, “the last person on set, we would all scream their name. If we were waiting for Ian McKellen, the whole of the Fellowship would start going, ‘Oh, we are just waiting for Ian McKellen!’” To commemorate the experience, the entire Fellowship got matching tattoos of the Elvish symbol for ‘9’.

Naturally, any triumph of good over evil was going to require much pummelling, slashing, stabbing and delivering of ugly enemies unto their makers. Thus the Fellowship were given expert training for months before shooting. For the swordplay, master Bob Anderson (who once taught Errol Flynn, no less) would put them through their paces. Bloom, who had to be a brilliant archer, spent his time firing arrows at paper plates in a unique spin on skeet shooting. As the shoot progressed and relationships developed with the stuntmen, the white heat of battle soon became second nature. “We got to know people’s body language so well that we got faster and faster, took more chances. It was like a dance partner you’ve worked with a long time,” says Mortensen.

But, given Jackson’s previous form, just how bloodthirsty could it get? “We pushed it as far as we could,” says Jackson slyly. Making the Orc blood black rather than red has allowed him some latitude. “It’s a PG, but I am pushing it...”

In December 2001, The Fellowship Of The Ring will be released on 10,000 screens worldwide. The poor Kazak Tolkienists may get their heads kicked in, but John Rhys-Davies, at least, is convinced the biggest opening ever is assured. At the 2001 Empire Awards, he confidently bet Empire a bottle of fine vino on this very issue. Jackson, meanwhile, will not be drawn. He just hopes people partake of some of the joy of his journey. “Hitchcock gave my favourite quote: ‘Where some people’s movies are slices of life, mine are slices of cake.’ I think that sums up what films should really do.”

This time, though, it’s the whole damn dessert trolley on offer.