The Exorcist is best known as the 1973 film directed by William Friedkin and starring young Linda Blair as the possessed Regan. Now, some four decades later, the film is being turned into a television series starring Geena Davis as the matriarch of a family dealing with demonic possession, which draws in a pair of very different priests who ultimately find that they have to work together to help this family and stop the spread of evil.

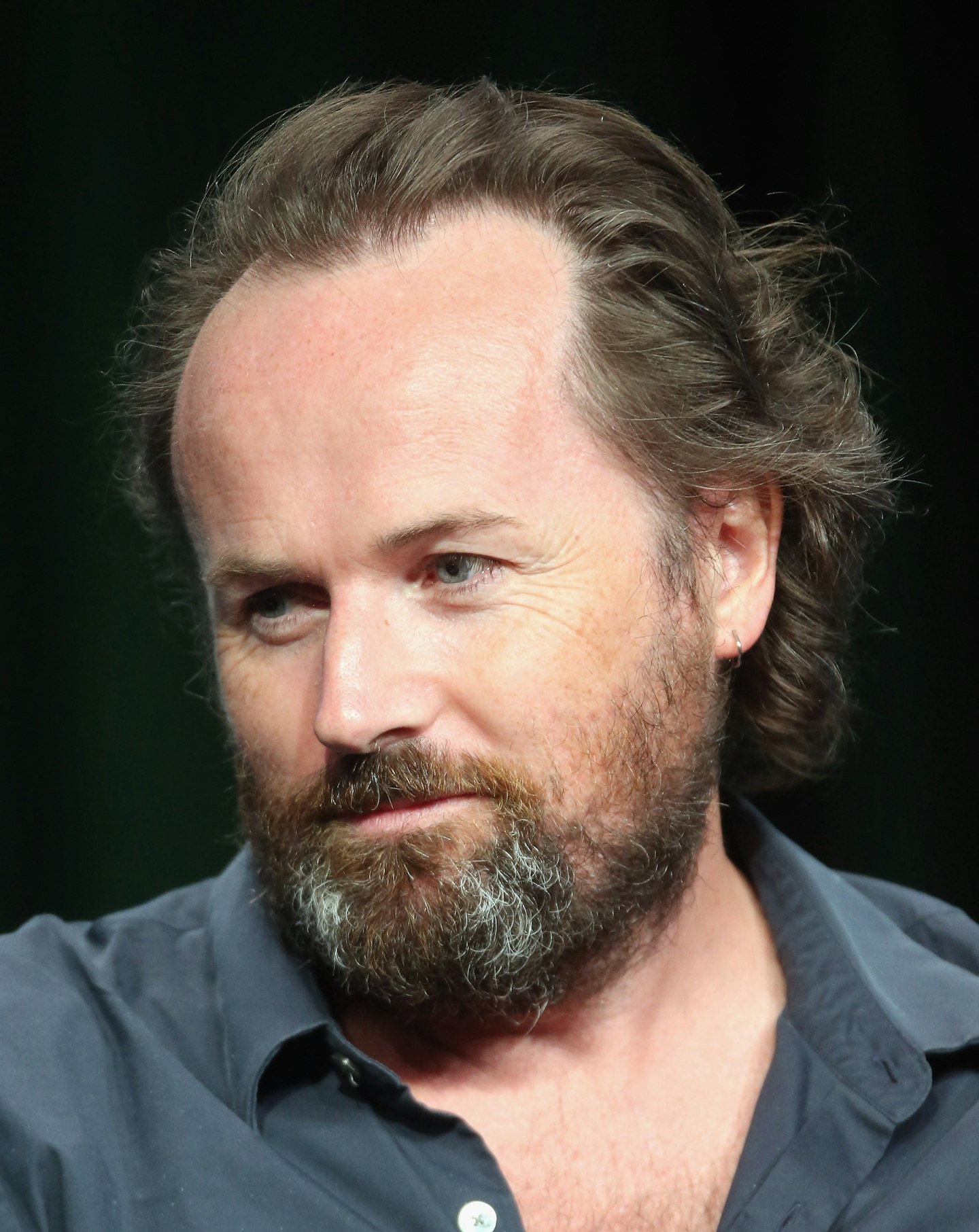

The pilot is directed by Rupert Wyatt, whose film credits include The Escapist, Rise Of The Planet Of The Apes and the remake of The Gambler. Although his name has been attached (before becoming detached) to a number of projects, among them Jurassic World and Gambit, it was The Exorcist that drew him in as both director and an executive producer. In this exclusive interview, he reveals why.

Your name has been associated with so many projects over the years, but this one went forward. What was it about The Exorcist?

Have you got all day? First of all, The Exorcist for television is very different. Ostensibly, as far as other projects are concerned, I have long been saying to myself that I’ve wanted to work with actors and projects from the ground up. That’s how I made my first film, and it took … God, ten years to get my first film off the ground, and I was at a place in my life where I was able to do that. I had no family commitments, and I was able to just grind it out, and eventually one day, it got the green light and it happened. Life gets more complicated and projects get more complicated after that. I think after doing Planet Of The Apes, and without going into too much detail, I was under certain obligations to continue down that path … From the perspective of what the studio wanted me to do, and what my agents wanted me to do, and to a certain extent what I wanted to do as well.

In terms of working on larger Hollywood films rather than pet projects?

I love Hollywood films and when they’re done right, they’re great. At the same time, I think it’s always hard to come on to something that preexists. Now I’m not necessarily saying this is the case with all these projects, but I would say that, sometimes when you’re trying to come in and segue into something that preexists, certain people don't want you to go back and rebuild from the ground up, because there’s a track already laid and there’s real estate. That’s totally fair enough, and so it can get very hard, and that’s not because of its creative voice, it’s to do with budget sometimes, it’s to do with circumstantial … There are so many reasons why, ultimately, a project won’t go. I think I’ve not been able to build my own projects for the last year, and now I am, and so that’s what I intend to do.

As far as The Exorcist is concerned, it was a television pilot. As we say in English, it does what it says on the tin, so it was as simple as, here’s the script, and you want to notice what the budget is for a television pilot on a network channel. I knew the elements involved, I knew my line producer, who I know is terrific; I knew the location we were going to shoot, which was Chicago. But for me, it always comes down to the most important thing, which is the script. Whilst when I first was approached about it, I said, “Why on Earth would anybody want to remake The Exorcist? No, thank you,” I was pushed to read it. I did and very quickly realized that this was by no means a remake, it was much more. It’s not a reboot. It’s not trying to dismiss the mythology that comes before. The events of the original film are tied into the mythology of the world that we’re in, but we are in the modern day, we are dealing with a wholly different story, different characters. Therein lies the great challenge to then try and create what is essentially, I think, the most interesting thing in modern film and TV today, which is visualizing the long-form novel. It’s why I think television is in its Golden Age, because people are approaching it like that. That’s what Jeremy Slater, the writer and creator, wanted to set out to do.

But because it is a novel for television, you’re essentially only writing the first chapter. Is that fulfilling as a director who might want to know how it all ends?

There’s all sorts of reasons to do pilots, and one of them, when it comes to being able to establish a particular tone and approach that will be carried forward. I am going to come back and do other episodes, but at the same time, I met with the showrunner, Rolin Jones, and very quickly had a real understanding that the steward of the whole process and the series was really strong, and had exactly the same sense of what could be that I did. I mean that in the sense of what it should be, which is one weird, visceral real world. We approached it like agnostics with no real desire to approach it in the hocus-pocus sense. That would be the challenge going forward, because we're faced with whether or not or how soon to reveal the Devil’s hand. That is Rolin’s job now, as the showrunner, to make sure that doesn’t happen. It’s really like a thriller or conspiracy.

Also, Chicago for me as a city was a great land to do that, because it is such an extraordinary city filled with so many complexities and contradictions in a certain way. It's not controversial to say that there's history of corruption within politics there, there's obviously the violence in Chicago, there's all sorts of reasons why the Devil would take a look at the city and say, "I have the opportunity to get under the skin of humanity and build from there and grow this pandemic, this Legion" into maybe where the show is headed. I'm speculating here, I'm not the creator, but if you imagine The Walking Dead but in The Exorcist sense, whole towns are possessed. That could be/should be where it's going.

Which is a fairly unique approach, the idea of a demonic possession spreading like a pandemic.

I think so.

Oftentimes with pilots the director will stick around to help set up the palette, so to speak, for other directors coming in. Are you involved in that capacity?

I remain as an executive producer, and actually I'm in Chicago this week to do exactly that. They're shooting right now, and I'm going in just as they're finishing up to be on the ground. I did this once before, directing a pilot for AMC, this show called Turn, but that was simply coming in to do the pilot and then really just moving on — the showrunner really felt he had it, and clearly he did, because they're four seasons in. But there was a little frustration from my part, I would say, as a filmmaker. My instincts are to want to tell the whole story, and be part of that. With this, that's something I'm enjoying the opportunity to do, for sure.

Despite your initial skepticism, what was it about the script for The Exorcist that changed your mind?

I think it all comes down to what I think I can do well. I love genre. I'm a massive fan of genre. I'm not a massive horror buff…Interestingly, this is my first horror anything, frankly, aside from a short film I made years ago. Rob Zombie and those directors are going to be way across and have a real understanding of how to jump scare. To me, I didn't know how to approach it in that way, so therefore I didn't attempt to approach it in that way. I used the frame, certainly, to be able to tell the story like I would across any genre. But I also used it in terms of the lighting and the blocking to really try and fully explore how to create a tone, a sense of unease. It goes back to what I was saying earlier about what we wanted to do with this. We didn't want this to be in the pantheon of modern horror. We wanted this to stay within, I guess, something like The Witch recently did so effectively. There aren't that many shocking moments in The Witch, but the pervasive sense of unease and creepiness in that film is remarkable. That's how I wanted to approach this. I knew I could do that, because I read the script and I very quickly visualized it in my head as I was reading it. I jumped on it immediately, as a result, because if there's a script that comes my way and I'm coming on to something that preexists, the only way I realize I could do a good job is if I see it, and in fact I did.

Without blowing anything, there are certainly key moments in the pilot that are genuinely frightening and that have absolutely nothing to do with shocks.

I guess it's always the things that feel the most plausible and feel the most accessible to an audience. We all have nightmares, we all wake up, we all have certain ideas of something that could be hiding around the corner and the question of does that really exist, but we get on with our lives. That's what we were trying to convey with these characters. In particular, Father Tomas, in terms of him walking away at the end, the James Dean shot I called it, because it's just his hands in his pockets walking through Times Square. I felt that I wanted to bring him back very quickly to the real world. Again, I think that's what the show is attempting to do throughout the entire season, is just keep everybody grounded in that place, rather than it all be malevolent evil and supernatural goings on.

To go back to the script, it was a very powerful piece of writing and the structure was great. Jeremy and I have very similar tastes in terms of the films that we love and that are our touchstones. It was clear to me when I read it that he loves Hitchcock’s The Birds. Cut from the pilot was a great scene where one of the girls sat on a fire escape at the back of the house and she finds herself surrounded by cats all staring at her. It was a great homage to Hitchcock's The Birds there with Tippi Hedren sitting on the school playground and they're all landing on the climbing frame.

How did that get cut?

Oh, man. With these things — and I wish it wasn't the case — the script's coming in around fifty-five minutes and you've got to get it down to forty-three minutes to get it out to network with commercial breaks. So you've got to kill babies, and it's only things that are really vital to the story that invariably stay. The fifty-three minute version was much closer to the version that I approached as filmmaker, because it has pacing in a way that you just can't necessarily achieve with network TV. But that said, some might argue that it's a hell of a lot tighter and more propulsive when it runs at that time. That's me being a director.

Was there anything from the Friedkin film that impacted you that you wanted to include, or did you go completely independent of the movie?

This really does not go anywhere near the narrative of the original film, other than thematic similarities and dealing with a family. But it certainly wasn't lost on me, the reason for the success of that film, which in my opinion lies so much within the filmmaking aspect of it and how it was approached. Friedkin's documentary background clearly played a huge part in how he approached things. When you watch that film now, obviously certain aspects of it you can watch and they feel of that period and no longer of our world, because so much has come in between. One has to remember that audiences at that time had never seen anything like that before, they'd never experienced the jump-scares, if you want to call them jump-scares. I hate the notion of gags and things like that, but the jump-scares in that film played out in these amazing moments. Like, you remember that shot where Chris MacNeil [Ellen Burstyn] runs up the stairs into the bedroom with the doctor, and then right in the middle of this exorcism, Linda's levitating over the bed? Chris suddenly gets smacked in the face. It just shocks audiences, because they'd never seen anything like it and of course now….

They've seen everything.

Exactly, pretty much. So it doesn't have quite the same effect today. Just from a sensible point of view, we're not attempting to repeat something that came forty years ago, but I do think what is timeless is how Friedkin approached the notion of belief in the real world. They’re having to explain something supernatural to another person who is invariably cynical or doubtful about it and unbelieving, because that’s how our world is. If you or I experienced anything that was supernatural, our audience after the fact would not really believe us. They would require firsthand experience. I think the Exorcist films that came after the original lost hold of that. They played to the stylization of the genre and the idea that we all live in this horror world when in fact we don't. We live in a very real world, and that's what I think makes it so effective. That's how I tried to approach this one.

What do you think the show is saying about faith and about the battle of good and evil in the world?

It goes without saying that there's a great deal of evil in the world, and there's a great deal of benevolence or good in the world. I think the choices that people make and the paths that people take in terms of how they explore their lives ultimately is what dictates which side of the coin you fall on. It sort of plays into the idea of those that become possessed. We met with this Catholic priest who gave us a great deal of insight into what possession really is, which is when you allow a demon into you. That is invariably when your world is broken. Those who have experienced a great deal of violence or committed a great deal of violence themselves, those who are existing in their own world of sadness and malevolence, essentially those are the ones that are most prone to possession. You don't just walk down the street and suddenly you get possessed. It creeps up on you.

When you hear it said in that way, it starts to take on a certain plausibility. I think people who are horrifically abused as children and then start to repeat the same thing to their own offspring or to others, you start to see evil inherent. That's what the Catholic Church feels is necessary to exorcise, to cleanse. It is in very basic terms a form of community outreach and a very practical form of therapy, in a really hardcore sense. I guess that's what we're trying to show. It's not hocus-pocus. Yes, there are instruments and tools to the Catholic priests. The exorcist's bag of tricks, the holy water, the stole he wears around his neck, those kind of actual things that he carries with him. But at the end of the day it's all about belief and belief in being able to cleanse somebody and make them better and purify them. That's how I saw it and that's how the actors I was working with approached it.

From the show's point of view, it's a question of "can they be cleansed? Can this be fixed? Can good triumph over evil?"

Right. And what’s interesting, and I didn’t actually know this, is that the Catholic Church doesn't believe in the Devil, i.e. Lucifer or whatever you call him. That’s a bit of a Christian phenomenon. They believe in demons. They don't think there is a yang to God's yin, so their belief in demon possession is actually just malevolent spirits inhabiting you. There is no single entity that's guiding them or directing them to possess beings. Now, when you know that, what's kind of interesting — again, without giving too much away — is maybe if an exorcist starts to think, “Hang on a second, no, there is a single evil entity that is directing this, that is creating his Legion,” and his belief is completely counter to his own church, then he suddenly becomes an outsider and very isolated in this conspiracy that, holy shit, there's a war coming.

In America, The Exorcist airs on Fox and in Britain on Syfy UK