Today marks Event Horizon's 20th birthday. That's two solid decades since Paul W.S. Anderson's space-bound horror took us to the edge of hell aboard a derelict spaceship, made Sam Neill terrifying and allowed Sean Pertwee to utter the immortal words, "This ship is fucked!" To celebrate this day of days we've reached all the way back to 1997 and dusted off Empire's original article, which first appeared in issue 99. Do you see? Do you see?"

"Layman's terms: you're a dead man," hardballs Laurence Fishburne, decked out in a green flightsuit and carrying a big fuck-off gun. He throws a tough-as-nails stare, then moves away, immediately stopping the moment he is off camera. It has to be said, emboldened by heroic lighting, he looks every inch the action icon - bullets would probably bounce off this man.

"Perfect!" shouts director Paul Anderson. "Let's do it again!"

In its heyday, the Event Horizon production covered seven soundstages on the vast backlot that is Pinewood Studios. But for today's additional shooting, they are reduced to the solitary K stage: sections of spaceship scenery are dotted around, each one designed to represent a major set in the movie. As Fishburne tries a number of variations on his hard nut dialogue, Anderson is racking up the take numbers - this is number 27 - shooting film like it's going out of fashion.

"Hey, Paul, are you trying to catch up with Stanley?" jibes Fishburne referring to Mr. Kubrick's legendary penchant for piling up the footage.

Yet Anderson's high shooting ratio has nothing to do with auteurist indulgence. Constantly referring to a video version of the assembled movie, he is trying to capture moments that have to slot seamlessly in with film shot several months previously. While the atmosphere is jovial, the pressure is on: to make the deadline for the film's August 15 US release date, the film has to finish within three weeks - this includes completing filming, editing, final sound mixing, titles and about 25 per cent of the effects shots.

"There's a real battle ahead of me," says producer Jeremy Bolt. "I have to keep the crew moving even though they are exhausted, working seven days a week, and their husbands and wives are leaving them. Everyone is at the end of their tether."

Let's make one thing clear. In traditional Hollywoodese, the phrase "additional shooting" is often a fanciful euphemism for "reshoots", the sure sign a film is in dire trouble (The Saint, anyone?). But in Event Horizon's case, the addendum to the schedule is for much less dramatic reasons - telling close-ups, dialogue and kiss-off lines - and is par for the big budget (in this case $50 million) course. Indeed, the agenda of this shoot was dictated by that great Tinseltown leveller - showing the assembled film to a proper audience in a test screening.

"You spend a year, a year-and-a-half on something," reflects Anderson, "and then in an hour-and-a-half, it's torn apart by some kids from Pasadena who go (Adopts Yank teenage voice), "Yo, that rocks!" or, "Man that sucks!" and it's great because the highs are incredibly high- you've got 350 people clapping - and the lows are, 'Oh God! What was I thinking?' It really helps you fine tune a movie."

The Movie in question is set in 2047. Missing for seven years, the Event Horizon, a prototype spaceship capable of using a black hole to travel faster than light, suddenly sends distress signals from somewhere near Neptune. A salvage crew - Fishburne (captain), Sam Neill (Event Horizon creator), Joely Richardson (navigator), Kathleen Quinlan (technician) and Sean Pertwee (pilot) - is dispatched to rescue any survivors and commandeer the ship. Once aboard, however, they begin to suffer the same hellish fate as the original crew: for the Event Horizon is "possessed", capable of looking inside your head and making your worst fears and dreads manifest...

I saw 20 years ago what the Alien could do and it still does the same thing. I think that's a problem with a lot of monster movies - how do you scare people with it?

The script was the brainchild of first-time screenwriter Phillip Eisner and underwent a spin by Seven scribe Andrew Kevin Walker who, according to Anderson, "punched up the darkness and the yeuch kind of stuff". Yet the screenplay was radically rejuvenated by the director, adding a vision Bolt describes as "a unique combination of reality and fantasy".

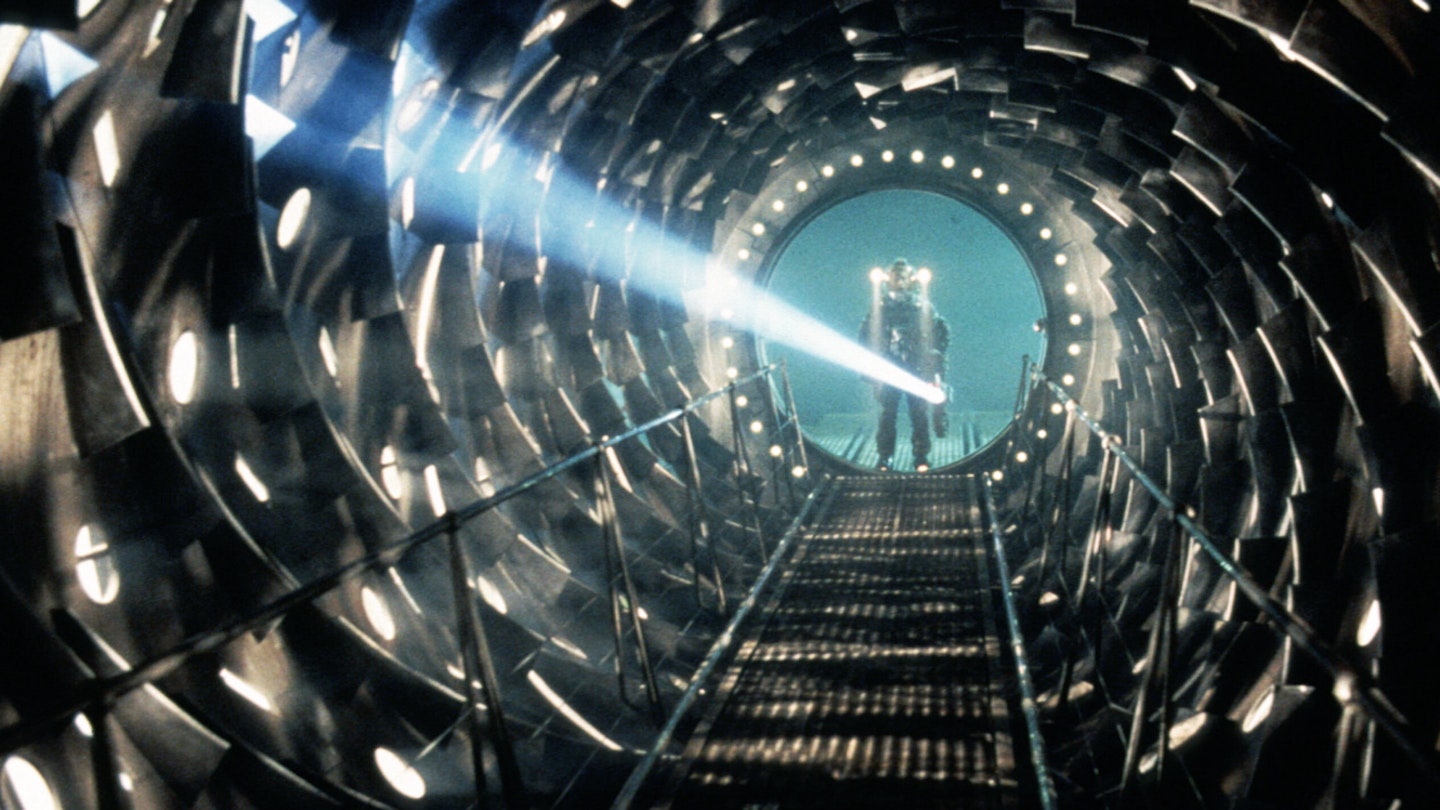

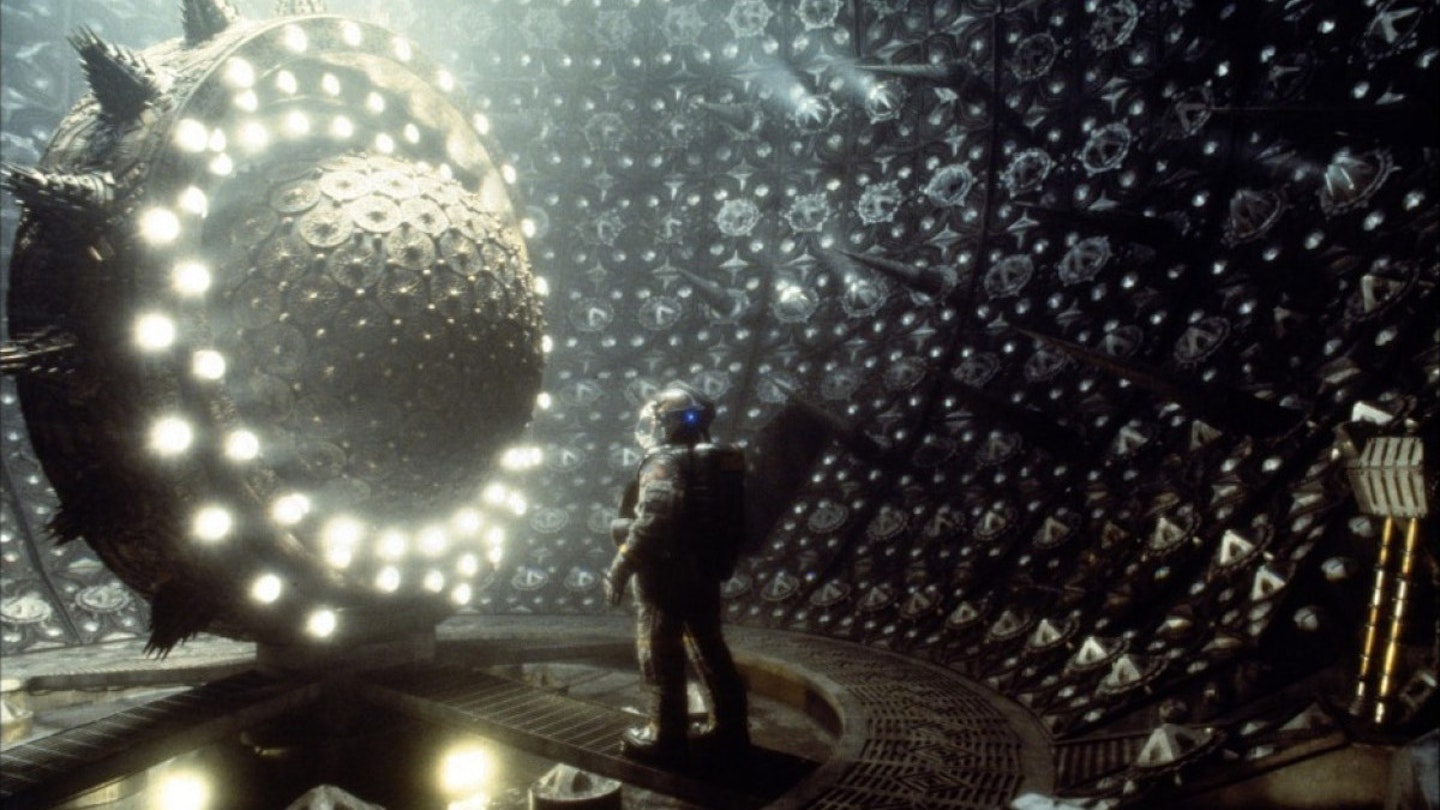

"We really tried to give the movie a special look," elucidates Anderson over the din of set construction, "to have an overall design style to stop it being bits of other space movies cobbled together. For the Event Horizon itself, the design style we came up with is sort of "techno medieval": when the lights are on it looks very technological, very 2001; when the lights go off, it looks like you're in some sort of medieval dungeon, Torquemada's torture chamber."

A lifelong fan of both horror and science fiction, Anderson jumped at the chance to combine his two favourite genres: Following his successful video game adaptation Mortal Kombat (number one at the US box office for three weeks), the young director actively sought scripts with an effects slant. This desire led to discussions about directing the Alien: Resurrection script - "It's got what you want from an Alien movie: guns and lots of Aliens running around" - yet he dropped out over scheduling difficulties.

"In a way, it would have been a great movie to do because I love Alien movies. But I've grown up with the Alien. I saw 20 years ago what the Alien could do and it still does the same thing. I think that's a problem with a lot of monster movies - how do you scare people with it?"

Still, the near brush with the exclusive Scott-Cameron-Fincher club brought into sharp focus how he should approach his latest opus. By describing the film variously as "The Shining/The Exorcist/The Haunting/Dante's Inferno... in space", Anderson and Bolt have very deliberately placed Event Horizon away from the man-in-a-suit scares of the Alien trilogy into a more psychological arena of horror - chiefly the haunted house movie.

"The strong thing about Event Horizon," he continues, "is that the monster is the ship, the thing you're afraid of is the dark inside everybody. In a conventional monster movie, the monster can only do what it can do. But with this film, if they're surrounded by the horror all the time, it can burst out at any moment."

"People willing to go through shit," says Anderson with admiration of his very co-operative cast. Indeed, putting as many top-flight actors through the mill as possible was high on the Bolt/Anderson agenda.

"It's rare that you get good actors in a science fiction film," he continues. "It's usually the last thing on a director's shopping list; great special effects, good sets and then actors are way down there with good catering."

Now after lunch, today's extracurricular filming has little of the gruelling nature of the original shoot - having said that, Fishburne is now submerged in a pool of not exactly bath temperature water, enveloped in smoke and dazed by lighting flashes - which also encompassed spinning Kathleen Quinlan around in a 65lb spacesuit on a giant steel fishing pole.

"Paul always did it with such a charming smile on his face," recalls Quinlan. "He had a good attitude and it made one willing to jump through whatever hoops he put in front of you."

There was also The Joely Richardson Bloodbath Incident.

"It's a major first for the British Film Industry," chuckles Anderson with relish. "Taking a Richardson and dumping nine tons of blood on them. Joely keeps saying, 'They never trained you for this at RADA. Sword fighting - yes. Hand-to-hand combat, strangulation and having blood dumped on you - no.'''

We actually used medical photographs and scanned in real beef steak and a cabbage leaf.

You have to be equally hardy to work on the film's visual effects. Laced up on the editing machine is one of the many visceral visions induced by the Event Horizon - a horrific close-up of an actor with his eyes gouged out. As well as being a job for prosthetic make up, VFX house Cinesite enhanced the shot by modelling computer generated cavities which were subsequently added to the eye sockets - instead of just seeing a flat contact lens, there are now depths, shadows and reflections inside the head."

"We actually used medical photographs and scanned in real beef steak and a cabbage leaf," says Cinesite's Helen Arnold, watching the images flicker on a small screen. "We were sitting in dailies completely serious saying, 'Do you think we should have a blood dribble here.' Once you sit in front of it, for so many hours a day, it loses its shock value."

Equally grisly is the image of a walking, talking man - affectionately known to the crew as "The Crispy Man"- licked and caressed by flames.

"An actor was obviously made up, then we had a mannequin made from a body cast of the actor," explains Bicknell. "We then pumped fire through the mannequin and then matched the two moves together: pulling the flames off the mannequin and pasting them on the actor." While bearing strong testament to Anderson's ability to create powerfully perverse imagery, such startling material did not go down too well with the American censors — a rough-cut version was recut after initially receiving an NC-17 by the MPAA ratings board, tantamount to box office poison in the US — yet Anderson believes the decision to hack back the horrors may have unwittingly contributed to a more unsettling experience.

"Sometimes what we found is actually trimming the gore down - making it faster - makes it more powerful. People talk about Seven like it's the most horrific, gory thing they've ever seen but what it does so cleverly is that it's very suggestive. That became our approach on this movie: show something that was just horrible then cut away from it so people could make it even more horrid in their own imagination."

"You sir," Laurence Fishburne tells Empire, in mock thesp tones, "are about to see a master of yelling and screaming."

Following the day's filming, Fishburne - coolly clad in pale blue jeans and orange polo shirt and moccasins - lifts himself off the black leather sofa where he has been stretched out for the last ten minutes and stands in front of a lectern, stretching and limbering up like a 100 metre sprinter. The reason for Fishburne's warning of extreme vocal activity is ADR - Automated Dialogue Replacement, the process by which actors post synchronise their lines to a scene in the serenity of a studio either because the original sound was unusable or to change an emphasis in performance.

"We have to do a lot of ADR," explains Anderson, "because the sets are obviously wooden so whenever anybody walks, no matter how good they look, it always sounds like someone walking on wood. So anytime there's been dialogue with any type of movement, we've had to loop all of that so we can replace it with clanking metal noises."

Watching Fishburne work is a spellbinding experience: hunched over, peering through squinted eyes, he screams, moans, pants and yells along with the picture; twisting and turning, buffeted by pretend air gusts then pulling himself up, hand over hand, on an imaginary rope, he recreates the onscreen action. Even more remarkable is the nonchalant way he snaps out of the frenzied activity, before calmly picking at the bunch of grapes laid on for him by the caterers.

Waiting for the take to be played back, Fishburne spins circles in a swivel chair and discusses with Anderson the security surrounding Kubrick's nearby Eyes Wide Shut set - "It's like Fort Knox 'round there," Fishburne quips. Suddenly, his hollering and howling fills the air, a little stark to the untrained ear without the other effects and music.

They go again - Fishburne instantly accessing the same level of intensity - until all are satisfied. Indeed, as the session proceeds, things begin to get a bit more playful: expertly matching his dialogue to the lip movements on screen, Fishburne begins to deliver his line ("Take me and leave my crew alone!") with a spot-on John Wayne impersonation ("Take me and leave my crew alone... you son of a bitch!"). The whole studio cracks up.

"That's on the end of the movie," jokes Anderson. "A little treat for all those who stay in the cinema for the end credits."

Standing beside a wickedly unflattering caricature of himself in the guise of a dictator, senior producer Alex Bicknell peruses a board where every effects image is reproduced in miniature to tracking the state of play of any given shot. The finished shots are marked "FINAL" ("It's very satisfactory stamping these babies," he notes) yet there are many more not yet completed. With so much riding on the quality of the effects and with time rapidly running out, the potential for stress is massive.

"We live at the bleeding edge of technology," admits production manager Courtney Vanderslice. "Sometimes Alex and I are at each other's throats. There is quite a bit of pressure."

In this respect, they are helped by their director.

"What Paul has," remarks Bicknell "is a very unique level of pragmatism and understanding which you don't generally find in that many directors. He knows what can be achieved and what buttons to press. And, also, he's very reasonable."

Still if the tension gets too much, the visual effects wizards have some orthodox ways to unwind (Bicknell mockingly calls the nearby boozer "the Cinesite Annexe,") and some unorthodox means, occasionally littering the frame with sly in-jokes.

"Apparently there is an X-Wing fighter from Star Wars on the side of the Event Horizon," laughs Bicknell. "Also, there's a floating book in a couple of shots, the Paul Anderson Autobiography By Cinesite Books Inc. He didn't ask for this by the way - he's not an egotist like that."

One guy dislocates his arm and forces it down his throat and rips out his stomach through his own mouth.

A few minutes out of the Twickenham sound studio, Anderson is stuck in traffic, watching the back of Fishburne's head in the car in front. It's edging towards nine in the evening and Anderson is travelling to

Cinesite to approve special effects shots, before returning to the cutting room for some witching hour editing. Yet he shows no sign of flagging, obviously in love with the whole process.

"I just think it's like the best job in the world," he enthuses. "I still can't believe I get paid for doing it. I'm not gonna be one of those directors who's gonna go (With feigned torment), 'Oh my life... my art!' I'm lucky to be doing this so I am going to enjoy it."

Later, in between making various calls on his mobile, he reflects on how Event Horizon has impinged on his social life ("You have to have very hardened friends. You don't see them very often"), retells the film's horrific-sounding orgy scene directed by chum Vadim Jean ("One guy dislocates his arm and forces it down his throat and rips out his stomach through his own mouth") and begins to pitch his next project, Soldier ("It's a futuristic Western starring Kurt Russell").

Moments later, Anderson notices that Fishburne is also on his mobile phone. This quintessential LA freeway moment - movie star, hotshot director, mobile phones, chauffeur-driven cars - now incongruously taking place on a suburban British A-road forces Anderson to send up the unreal mollycoddling granted those within moviemaking.

"Film people," he notes, now off the blower. "We're crap, aren't we?"

This article first appeared in the September 1997 issue of Empire.