This article first appeared in Empire Magazine issue #315 (September 2015).

Far out in the unknown regions of the Moddell Sector of the Outer Rim Territories lies a small, unregarded green moon. Its inhabitants refer to it as any one of a number of bizarre chirps, squeaks or roars, but to the rest of the galaxy far, far away, it’s known as Endor. A long time ago (1983, in fact) it was an outpost of the Empire: the construction base for the second Death Star, which the Rebellion destroyed before its completion in Return Of The Jedi. But Star Wars’ sixth episode wasn’t our only visit to the verdant home of the Ewoks. Even disregarding the multiple further adventures detailed in Star Wars’ ‘Expanded Universe’ of novels, comics, games and animations, audiences were granted two return visits in 1984 and 1985.

J. J. Abrams’ The Force Awakens is heralding a new Star Wars era in which the numbered episodes will alternate with standalone spin-off adventures, making for a film per year. But the Ewok adventures Caravan Of Courage and The Battle For Endor demonstrate that the side stories are hardly a new idea. Made to capitalise on the popularity of the warrior teddy bears among Star Wars’ younger fans, they were also, more sentimentally, a gift from George Lucas to his young daughter, Amanda.

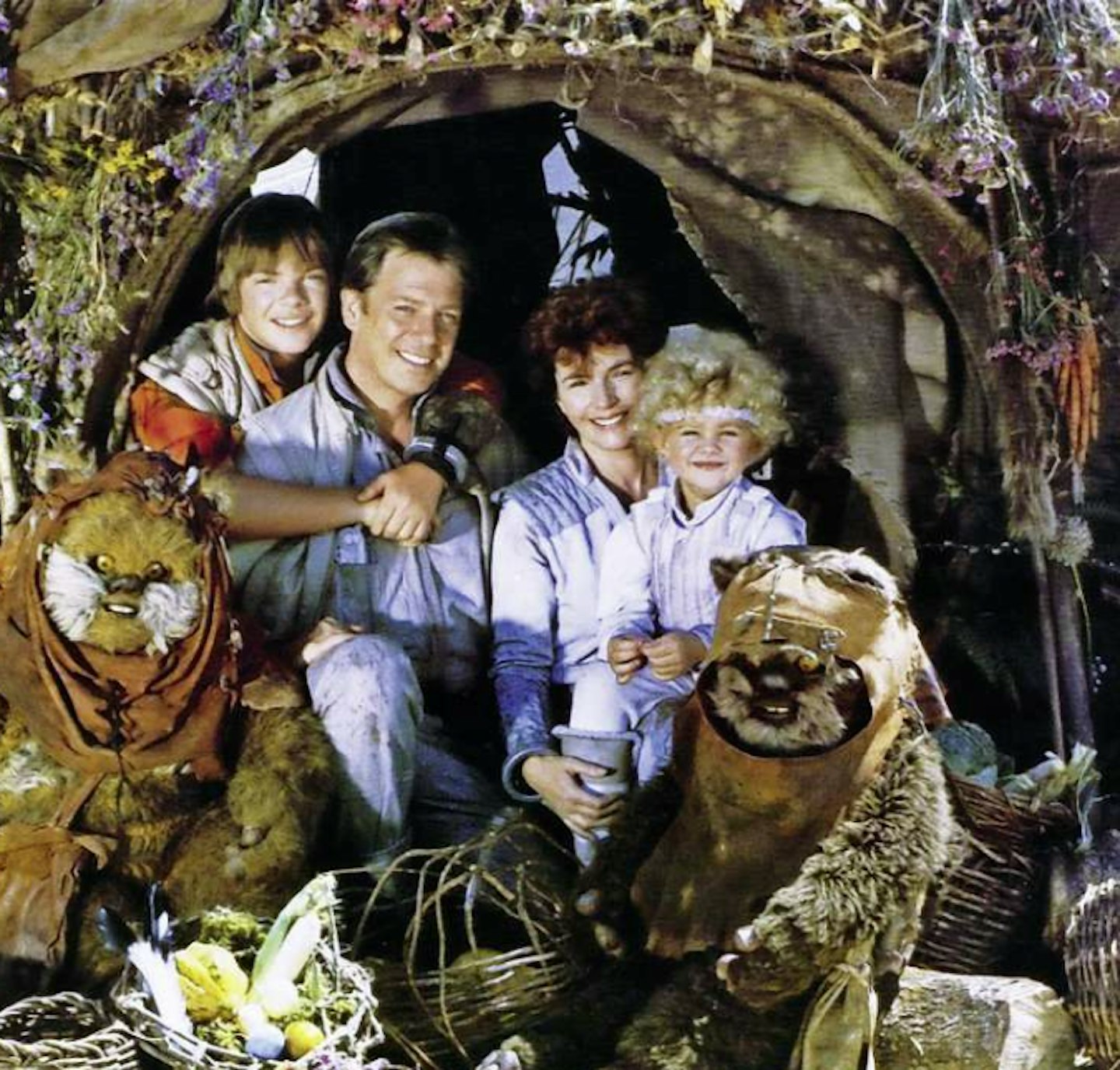

Initially conceived as The Ewok Holiday Special, the first of the films soon found its name changed to avoid any sort of association with the infamous Star Wars Holiday Special of 1978. It was also a story that grew in the telling, expanding from an hour to feature-length. Its focus was the early-teen Mace Towani (Eric Walker) and his little sister Cindel (Aubree Miller), as they joined Wicket (Warwick Davis) and his fuzzy Bright Tree Village companions on a quest to rescue the Towani parents (Fionnula Flanagan and Guy Boyd) from the clutches of the monstrous Gorax. In the second film, both parents and Mace are killed early, leaving Cindel alone with the bears, some evil Sanyassan Marauders, and an irascible hermit played by Wilford Brimley.

Miller remembers little of the experience; understandably, since she was only four years old at the time. For Walker, however, the Star Wars franchise’s first Mace, 15 years before Samuel L. Jackson’s, it remains the role of a lifetime, despite his having discovered the films comparatively late.

“I actually wasn’t really a Star Wars kid,” he says. “I didn’t have Star Wars toys, although George sent me a lot as Christmas presents subsequently. I would’ve been about seven when Star Wars came out, but I was not really going to movies until Return Of The Jedi. I saw that one about ten times!”

Walker was initially unaware he was auditioning for George Lucas. An interview with the casting team led to an on-camera try-out, “but it wasn’t until the final screen test that I realised what the film was,” he laughs. “They brought out an Ewok attached to a stick — it didn’t have an actor in it — to see if Aubree would be afraid of it, but she thought it was cute and hugged it. So they didn’t have a problem there.” Lucas came up with Caravan Of Courage’s story, with screenplay duties going to Bob Carrau, at the time working for Lucas as Amanda’s nanny. The director was John Korty, a veteran filmmaker and animator who’d been an influence on both Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, and for a time rented space at Coppola’s American Zoetrope. Several of the rest of the crew — production designer Joe Johnston, special-effects artist Phil Tippett, many of the Ewoks themselves — came straight from Return Of The Jedi. The redwood forests around Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch in Marin County, California, again played the part of Endor.

Filming was relatively straightforward, barring some tweaks to the script to soften Walker’s character. “He was way meaner as written,” Walker says, explaining why Mace is introduced as a problem child, but for the most part seems perfectly reasonable. Walker got to wear a Luke Skywalker- style orange flight suit and crash into the Ewoks’ hut wielding a blaster, an experience he describes as “awesome”.

When Korty’s prior commitments made him unavailable for re-shoots, however, Lucas himself stepped in for a week of filming at the end of the schedule. “A lot of people don’t realise that,” Walker says. “The official line is that George didn’t direct after Star Wars until The Phantom Menace, but that’s not quite true.” The re-mounted scenes included one in which Mace is trapped underwater (“Pounding on a sheet of Plexiglas!”), and another where his hand is bitten when he unwisely sticks it into a tree. In the original version his assailant was a flower, but in the new scene it became a creature: actually the same puppet used in The Empire Strikes Back for the giant asteroid worm.

The official line is that George didn’t direct after Star Wars until The Phantom Menace, but that’s not quite true.

“I still have the call sheet from the first day of reshoots that lists George as the director,” Walker tells us. “I think the assistant director got in trouble for that!” For the rest of the week, Korty’s name reappeared to maintain the secret of Lucas’ hands-on involvement.

Caravan Of Courage premiered on American television on November 25, 1984 (it was also released theatrically in several countries, including the UK, over the next few months). Star Wars fans anticipating a grand new adventure were disappointed by the kid-friendly tone and slow, episodic pace. It resembles a Star Wars film less than a fairy-tale quest

to confront an ogre in a castle, with sentimental narration by the singer Burl Ives papering over the narrative cracks. Nevertheless, it was an enormous success, pulling in an astonishing 65 million viewers and garnering Emmy nominations for Outstanding Children’s Programming and Outstanding Special Visual Effects. It won for the latter. Arriving in the very early days of VHS, it was one of the first massively home-recorded events in television history. A follow-up was inevitable. The slightly more uptempo Battle For Endor was broadcast a year (less a day) later.

The Battle For Endor’s story was the result of a handful of brainstorming sessions between Lucas, Johnston, Tippett and writer-directors Ken and Jim Wheat: Lucas protégés who would go on to start the Riddick franchise with Pitch Black. Since Amanda Lucas had been distraught at the death of Chukha-Trok in the first film, no Ewoks would be offed this time, although the Towanis were apparently fair game, much to Walker’s disappointment. He returned for a single scene, battling Marauders until he’s blown up. During the writing and designing process, Joe Johnston provided Lucas with three rubber stamps: “Great”, “CBB” (could be better) and “86”. “He was like a kid with a new toy when he saw those,” Ken Wheat later recalled. “There was no way anybody could ever be confused about his choices.”

The eventual story saw the orphaned Cindel (Miller again) and Wicket (Davis again) forming an uneasy new family unit with the crashed and stranded spacefarer Noa (Brimley).

The hulking Marauder antagonists, lead by Carel Struycken (aka the Addams Family movies’ Lurch) in Grinch-esque prosthetics, are looking to harness the power of a unit from Noa’s old ship, which they’re under the impression is a magical artifact. Siân Phillips plays a Nightsister who can turn into a crow with the aid of a magic ring.

Ken Wheat recalled the experience as “more like play than work”, but did concede a period when “things got completely crazy”. This is a veiled reference to problems caused on set by Brimley, who began railing against being expected to act against puppets; dubbed the Wheats “the Idiot Brothers”; and eventually refused to be directed by anyone other than Joe Johnston, still on board as production designer.

“The Wheats would have to discuss what they wanted with Joe,” says cinematographer Isidore Mankofsky, “and then hide behind a set or around a corner or something while Joe directed Wilford!” The character of Teek, a speedy, buck-toothed Endor creature who lives with Noa and gets on his nerves, was hurriedly re-worked to be played by actress Niki Botelho rather than puppeteers. But even given that concession, Teek and Noa still share the same frame in the finished film conspicuously rarely. Some later shots during the castle sequences, where Brimley’s face is obscured, even seem to suggest that the actor was occasionally replaced with a body-double. Mankofsky, however, maintains that it is always Brimley: those were simply the days when he was being especially cantankerous, refusing to even lift his head or hat brim for the camera.

“I never did find out what was between him and the Wheats,” Mankofsky says. “They were new directors, but they were good; they certainly weren’t lost. I’d give them a B-plus or an A-minus!”

“It might have had to do with Wilford just wanting to work with Joe Johnston, who everybody knew was George’s heir apparent,” unit production manager Frank Simeone muses. “But Joe didn’t like being brought into this drama that he had nothing to do with. He was minding his own business and all of a sudden he was being told he had to direct Wilford.”

Far from having Lucas on-hand for reshoots, on this occasion the production had a directive not to bother its overseer with any day-to-day problems. “He had a few months there where he’d decided he was going to just chill and race cars,” says Simeone. “But when Wilford started acting out we had to bring that to George’s attention, and George and (producer) Thomas G. Smith basically read Wilford the law. From then on he behaved; it went forward after that!” In Brimley’s defence, Walker recalls Brimley taking all the children (principals and stand-ins) for dinner and to the premiere of Cocoon. So he wasn’t grumpy all the time. The Battle For Endor, however, played to a smaller television audience than Caravan Of Courage, and while the actors’ contracts had been drawn up for a trilogy, a third film never materialised. We last see Cindel and Noa flying off in his repaired ship, but Brimley, probably to his relief, wasn’t required for further adventures.

Posterity hasn’t been kind to the Ewok films. Their television roots obviously render them smaller-scale affairs than the trilogy that spawned them, but The Battle For Endor, in particular, compares favourably to Lucasfilm’s theatrical Willow, released three years later. And it’s a lot better than Howard The Duck. What’s odd about both films, however, is that they don’t feel very much like Star Wars. The magic and mysticism of this Endor feels at odds with the rest of the universe; even one where the Force is at play. There’s none of the films’ iconic sound design, and the production design too contains little that’s familiar, bar some of the Ewoks’ contraptions, the odd costume and weapon, and some creatures in the second film that look like Dewbacks.

Those films had heart, which I don’t think you can really say about the prequel trilogy.

There’s a certain amount of confusion about when they’re even set. Walker says that, during production, the understanding was that they’re more than a century on from Return Of The Jedi: Ewoks are long-lived! That makes sense of Wicket’s ability to speak English (or “Basic" in Star Wars parlance) and his interest in “Star Cruiser!”: something he would remember from his youth. But subsequent official edicts have placed the two films between episodes V and VI. Michael P. Kube-McDowell’s novel Tyrant’s Test, set just a decade or so after Jedi, contains a brief mention of Cindel, and reveals she grew up to be a journalist on Coruscant. It’s the Expanded Universe’s sole callback to either of the TV movies.

The core Star Wars films have all seen multiple lavish home-releases and infamous FX overhauls (including CG eyelids for the otherwise glassy-eyed Ewoks), but the Ewok adventures have only received a single bare-bones DVD release, long out of print. These days, they’re barely even considered canon.

“It’s a shame, those films had heart,” shrugs Walker, “which I don’t think you can really say about the prequel trilogy. I’m hoping J.J. Abrams brings that back. It looks as if he has, and that Star Wars is in excellent hands. I still meet and talk to people that like Caravan Of Courage and The Battle For Endor and remember them fondly from their childhoods. Other people don’t like them because they don’t like the Ewoks. There are a lot of Ewok haters out there. But we weren’t as bad as Jar Jar!"