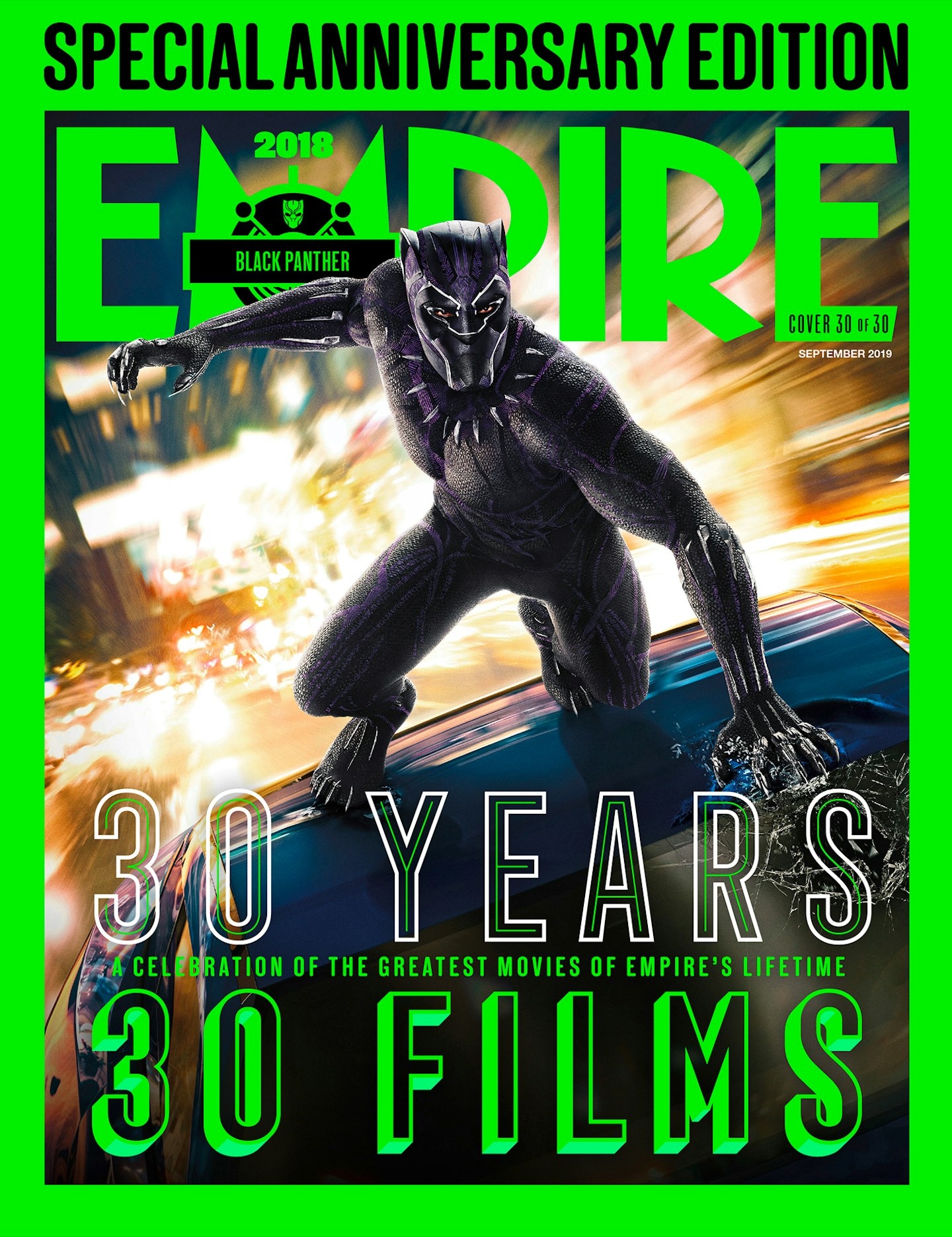

For our 30th Anniversary Special Edition issue, we picked the 30 films from the last 30 years that have defined Empire’s lifetime, but some favourites didn’t quite make the cut. Nick de Semlyen argues the case for Children Of Men.

Gravity was the Alfonso Cuarón sci-fi film that made it onto the 30 list, and I’ve got no beef with the choice — when it comes to ticking-clock, high-velocity thrillers involving Sandra Bullock and metal things exploding, it’s right up there with Speed. But for me the earthbound Children Of Men is just as worthy of a spot. Cuarón’s second UK-set drama (the first was 1998’s Great Expectations, a film with fewer Banksys), it takes our green and pleasant land and makes it look non-stop nightmarish. None of the issues it tackles have exactly improved over the past 13 years, and with Britain poised for an even bumpier time, it’s only getting more relevant by the day. Call it ‘No Deal Brexit: The Movie’.

Even by the standards of sci-fi cinema, a dingy, dread-filled genre at best, Children Of Men is bleak as heck. It rapidly establishes that we’re in 2027 and on a babyless Earth where things are hurtling downhill fast (a newspaper clipping, one of the many bits of printed exposition the camera glides past, states that Kazhakstan has been nuked by Russia). It also sets up that the UK is both the country that’s comparatively in the best shape, and still a flaming shithole. In a superb introductory shot, hungover hero Theo (Clive Owen) wanders out of a coffee shop and onto a London street thick with police, lousy with refuse and with more awful news flashing up on neon screens. Then, as a punchline, a bomb goes off. Later, there are caged immigrants, militarised train stations, lines of riot troopers. The world-building is astonishing — surreal moments of beauty, like a zebra being walked like a dog, are perfectly placed — taking us on a tour, along with Theo and the miraculously pregnant Kee (a terrific, should-be-in-films-more Clare-Hope Ashitey) through locations that are familiar enough to feel real, but alien enough to feel terrifying.

One of Cuarón’s inspirations was grim docu-film The Battle Of Algiers. But wisely he studs his own movie with humour, thanks partly to the sardonic Theo (“Baby Diego? Come on, the guy was a wanker”), partly to Michael Caine’s goofy Jaspar (a political cartoonist turned drug dealer, whom Caine based on John Lennon), and partly to the director’s own visual grace notes (an inflatable pig above Battersea Power Station, a nod to Pink Floyd). Its sheer energy and inventiveness also stops it from feeling like a total downer.

Cuarón’s signature protracted shots (or, as bores as dinner parties like to call them, “oners”), which he’s since deployed on a beach in Roma and in outer space in Gravity, are here at their most dazzling, not least in an inside-a-car scene that electrifies as a horde of maniacs descends on the heroes’ vehicle, assaulting it from all sides. At all times the film’s action feels immediate, vivid, real. Even the bits where Michael Caine pulls his finger and farts.

It’s a dark ride that makes you feel battered and fearful for the future. But it also inspires a sense of elation and, ultimately, hope. As the climactic sequence where Kee gives birth and the baby is hoisted aloft by Theo demonstrates, nothing is ever over. And with Cuarón behind the camera, there seems no limit to the magic that can be achieved. That mewling, blinking, realer-than-real baby, after all, is made entirely of pixels.

Read Empire's list of the 30 films that define the last 30 years.

READ MORE: The One That Got Away – Schindler’s List

READ MORE: The One That Got Away – Star Wars: The Force Awakens

READ MORE: The One That Got Away – True Romance

Empire's 30th Anniversary Edition Covers

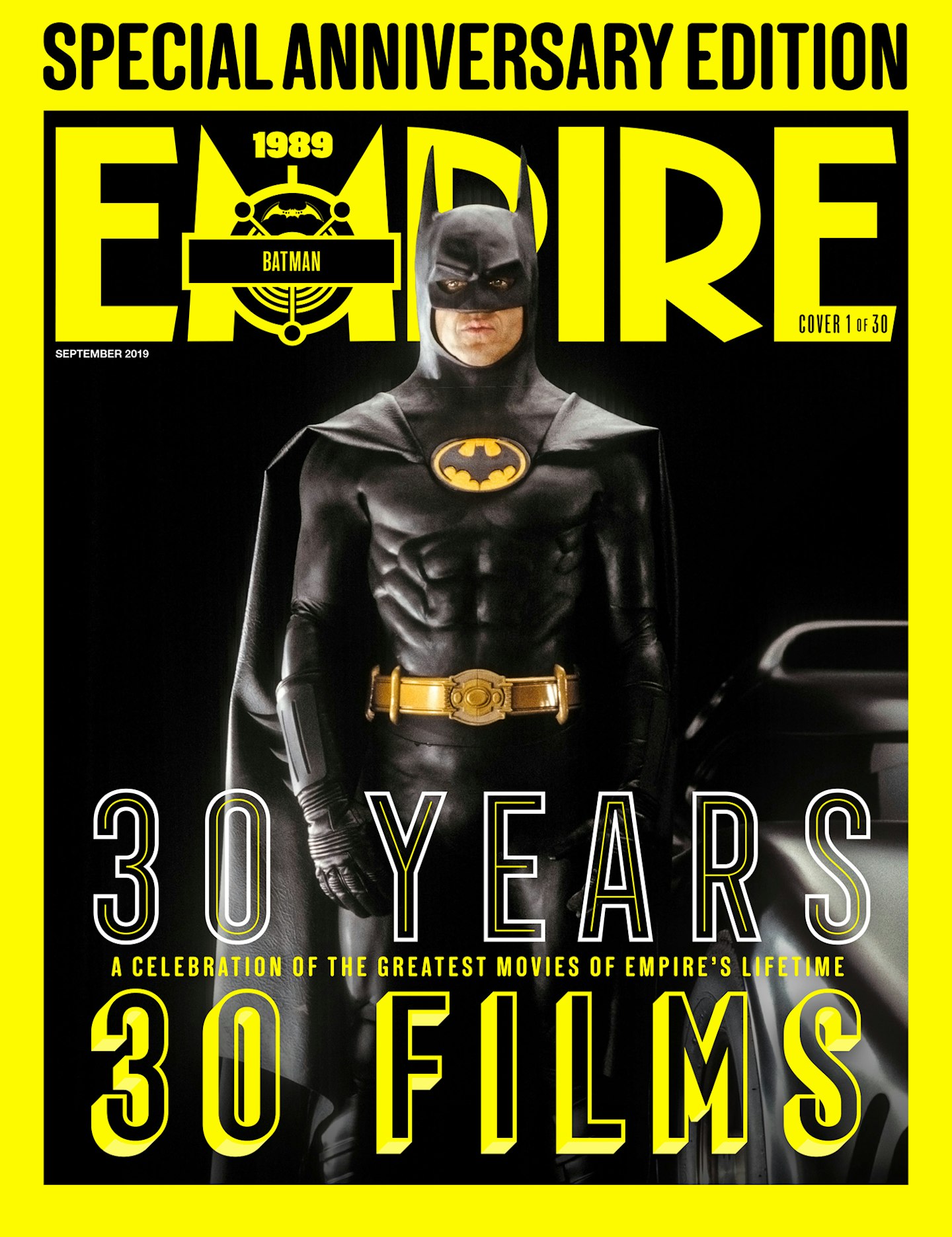

1 of 30

1 of 30#1 – Batman (Tim Burton, 1989)

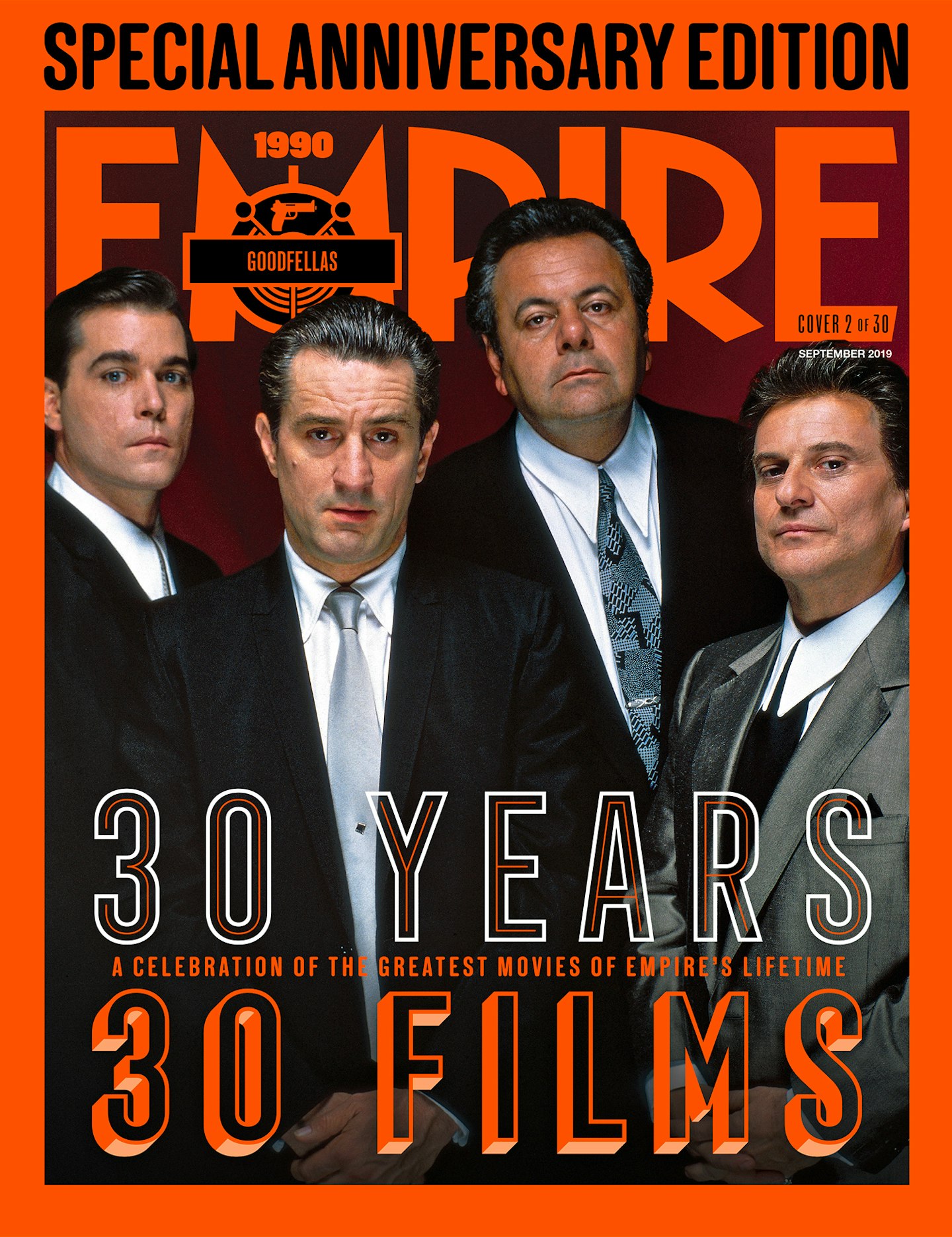

2 of 30

2 of 30#2 – Goodfellas (Martin Scorsese, 1990)

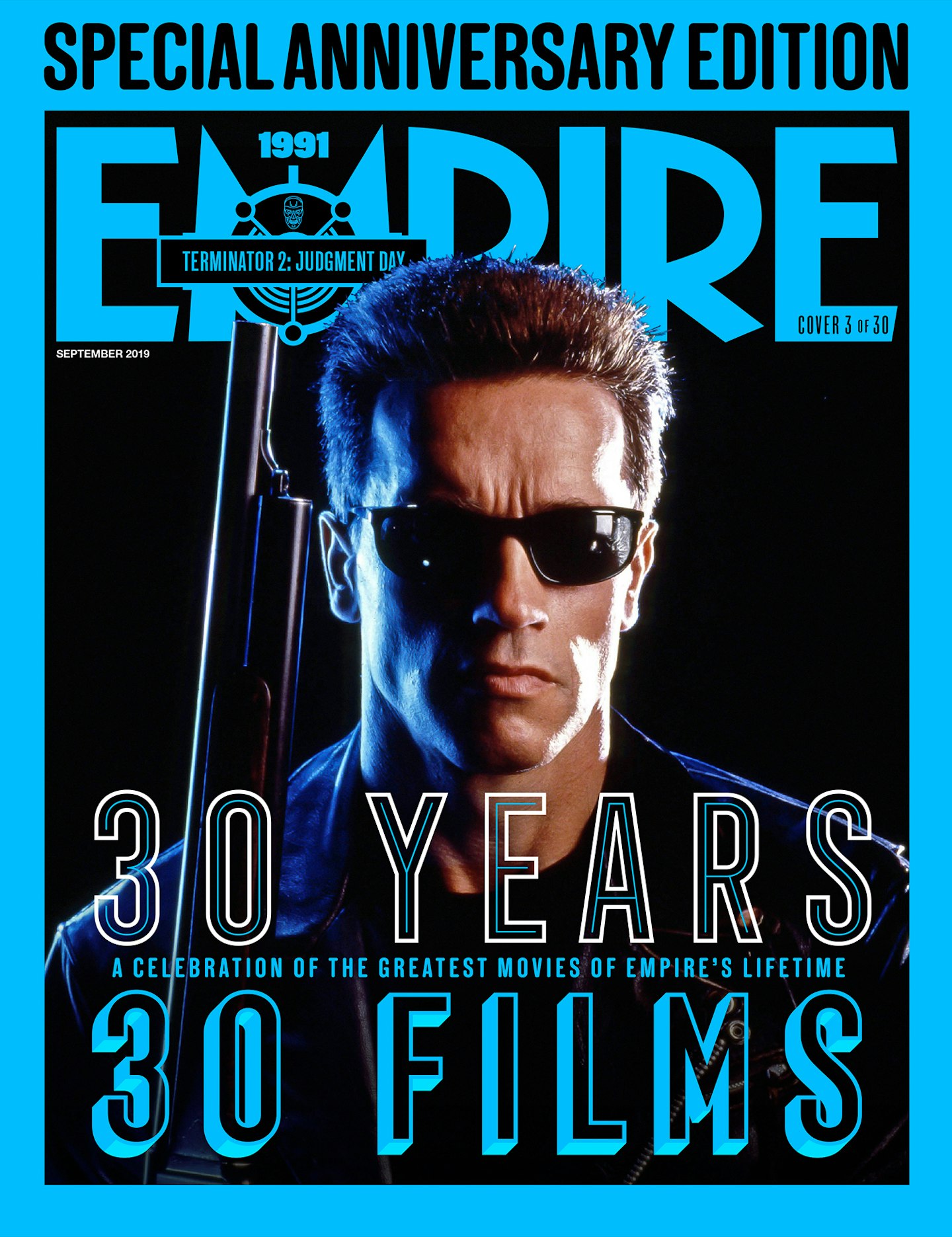

3 of 30

3 of 30#3 – Terminator 2: Judgment Day (James Cameron, 1991)

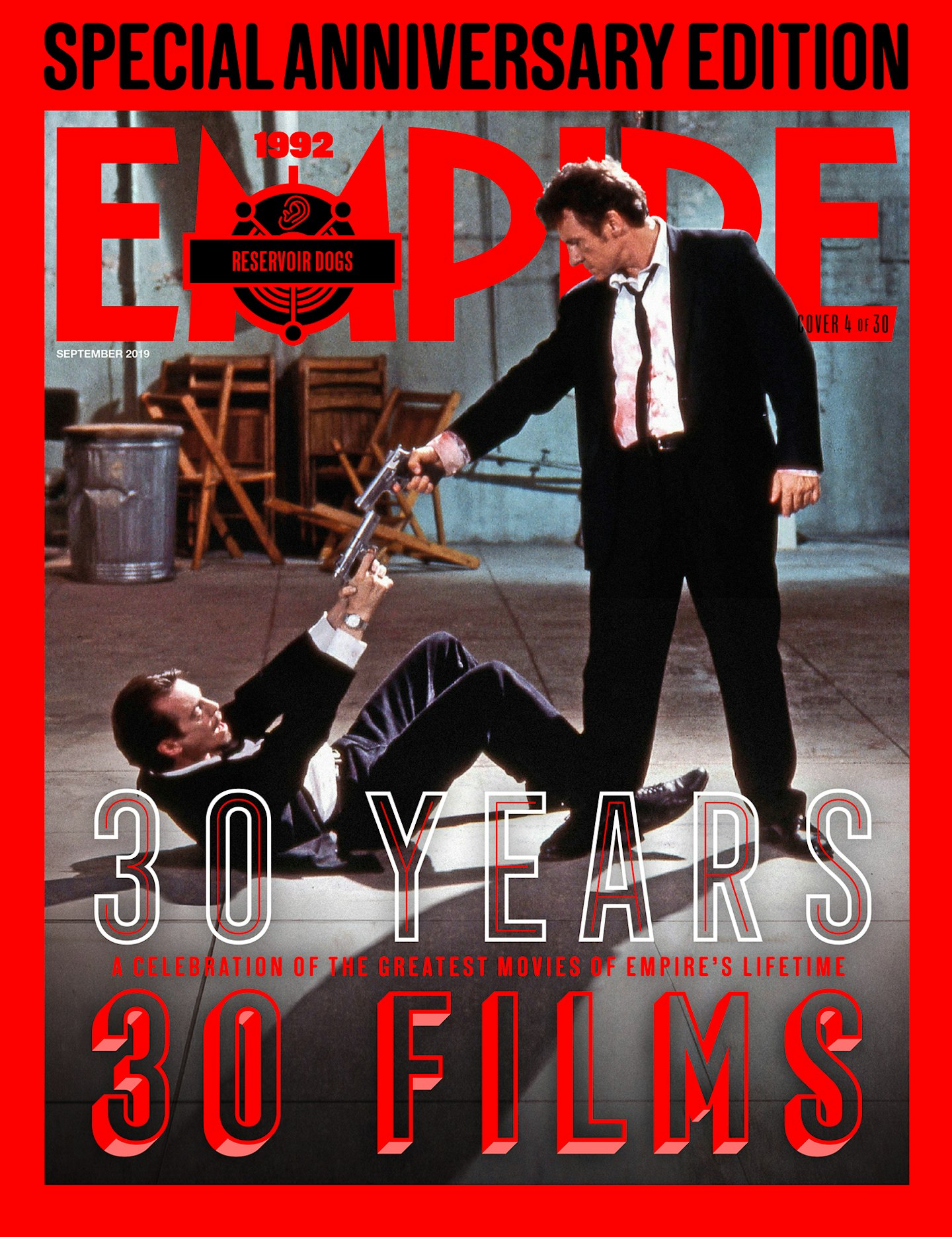

4 of 30

4 of 30#4 – Reservoir Dogs

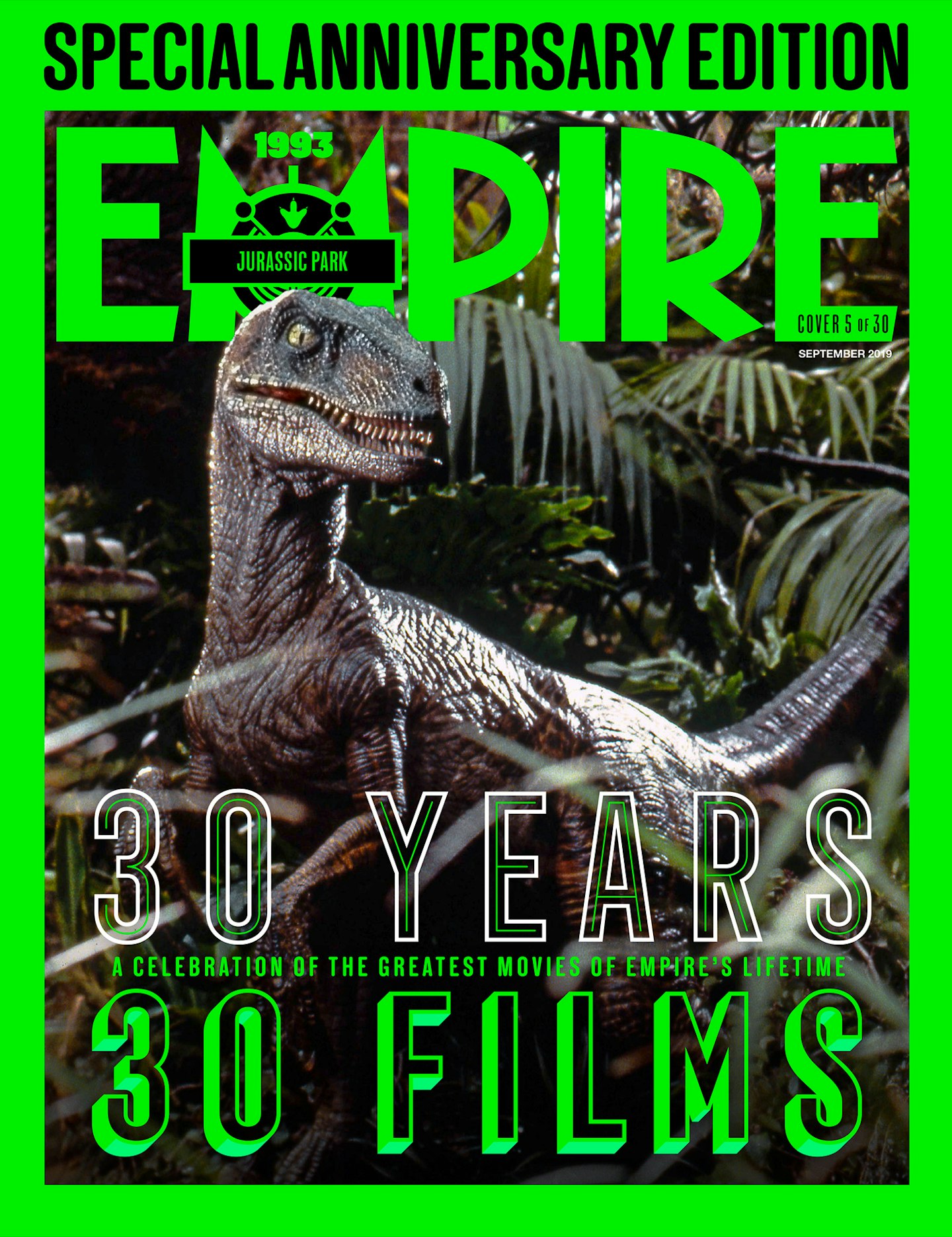

5 of 30

5 of 30#5 – Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, 1993)

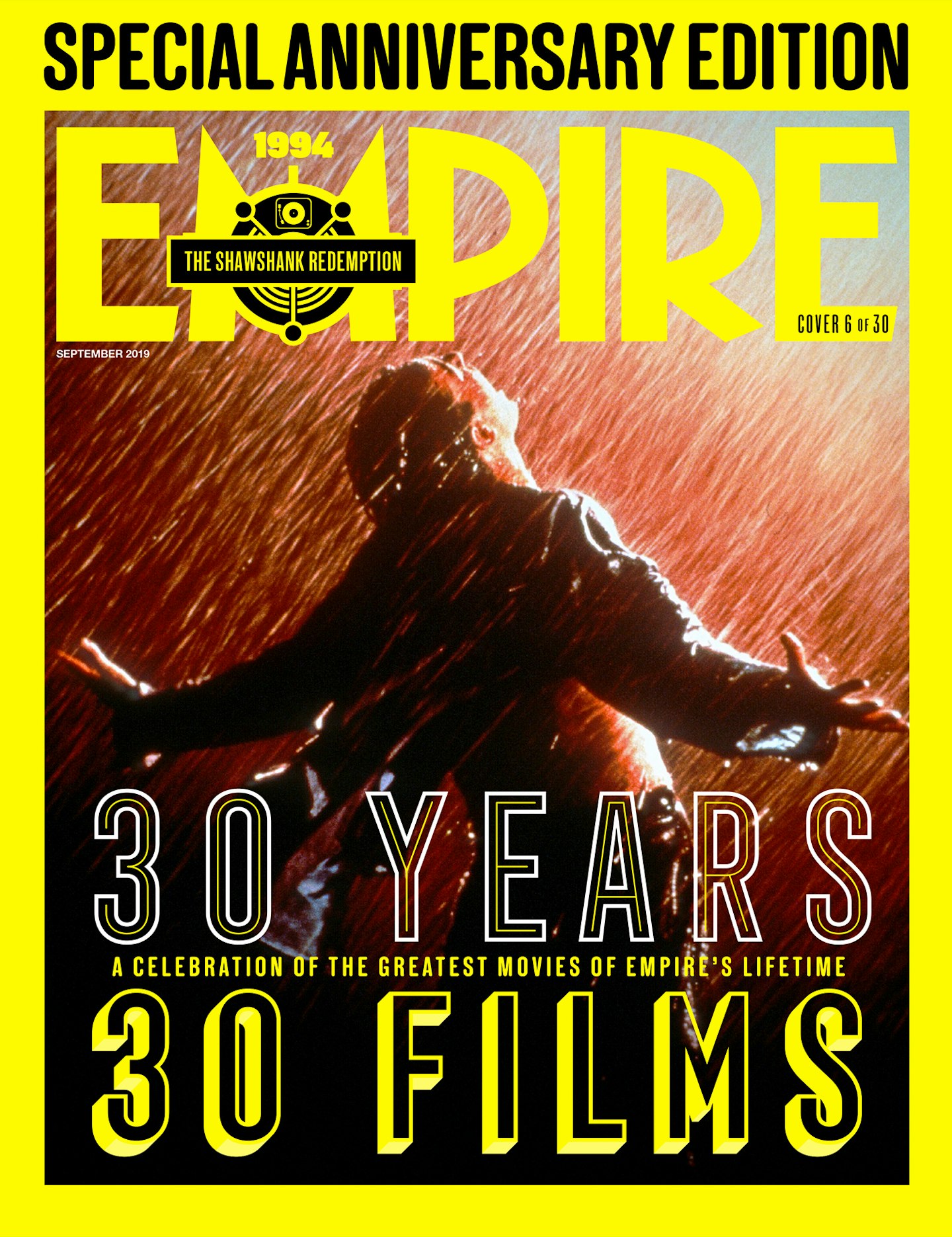

6 of 30

6 of 30#6 – The Shawshank Redemption (Frank Darabont, 1994)

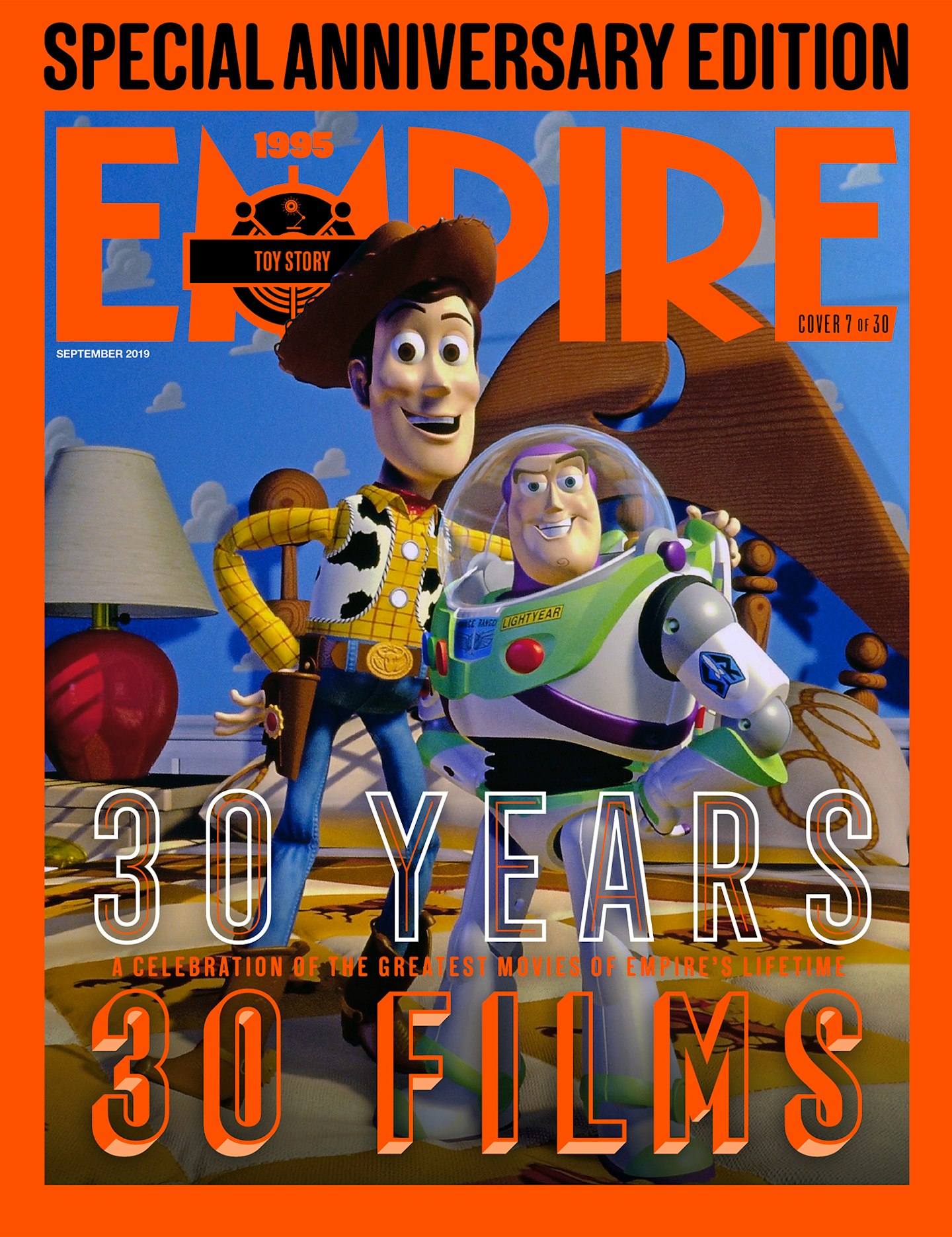

7 of 30

7 of 30#7 – Toy Story (John Lasseter, 1995)

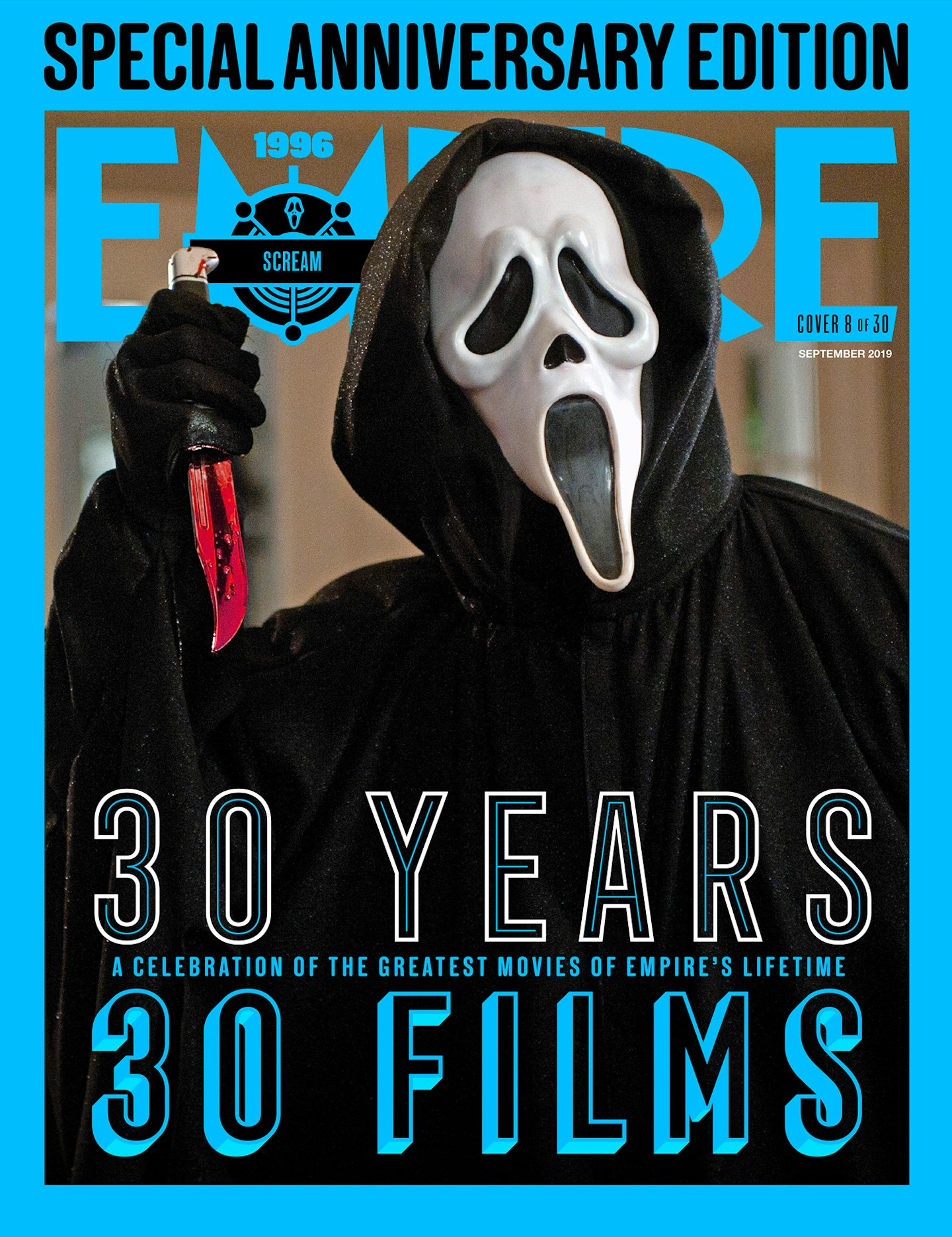

8 of 30

8 of 30#8 – Scream (Wes Craven, 1996)

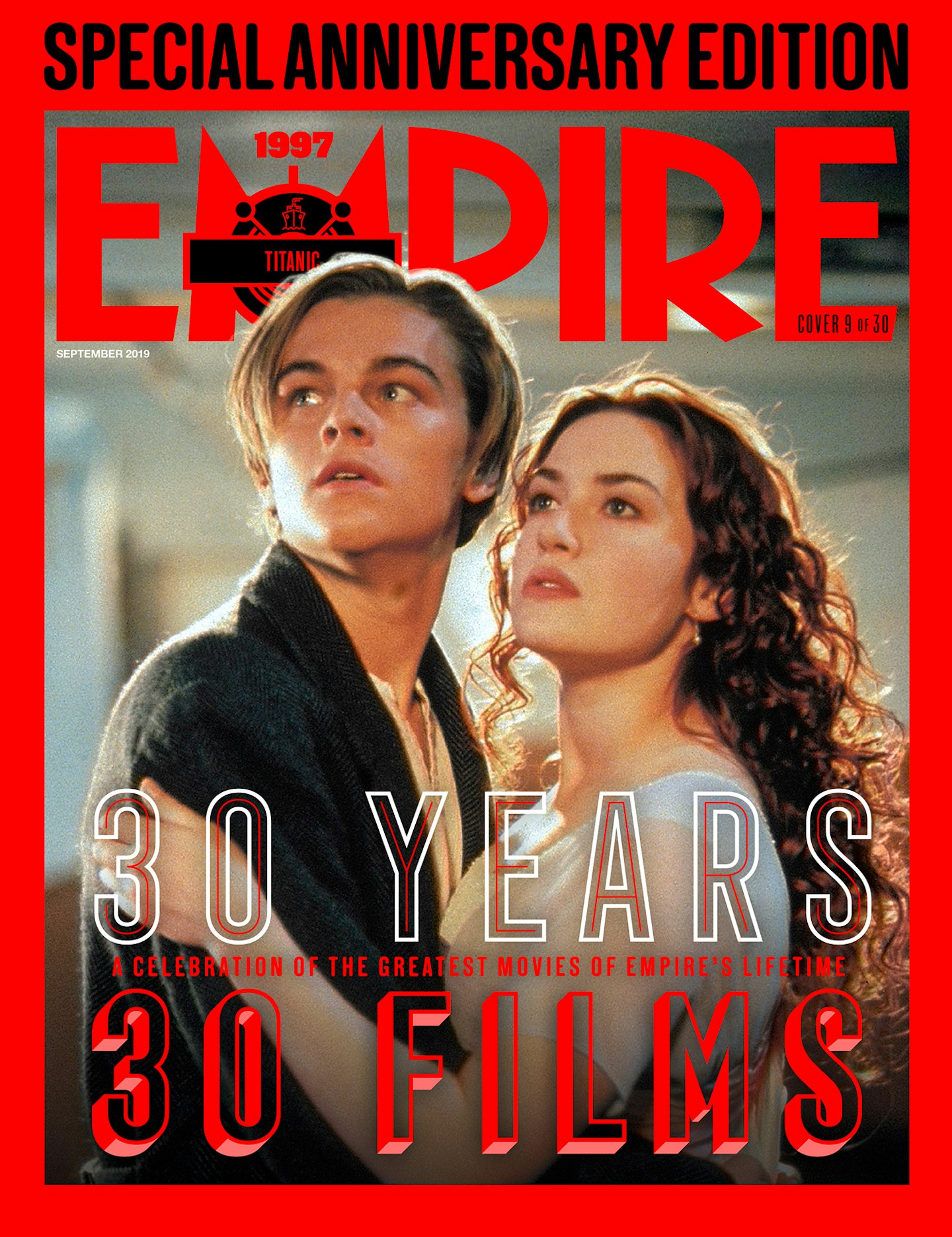

9 of 30

9 of 30#9 – Titanic (James Cameron, 1997)

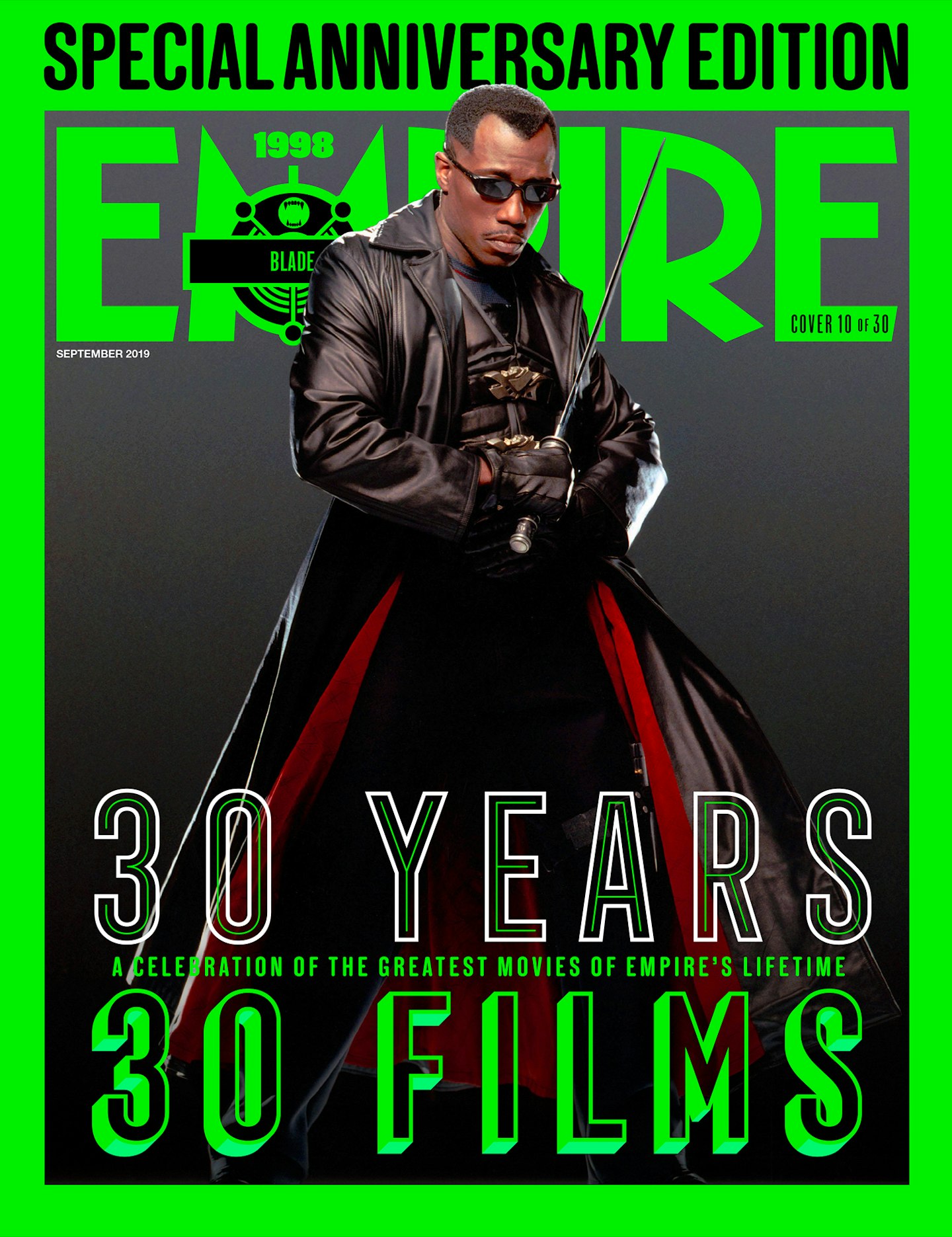

10 of 30

10 of 30#10 – Blade (Stephen Norrington, 1998)

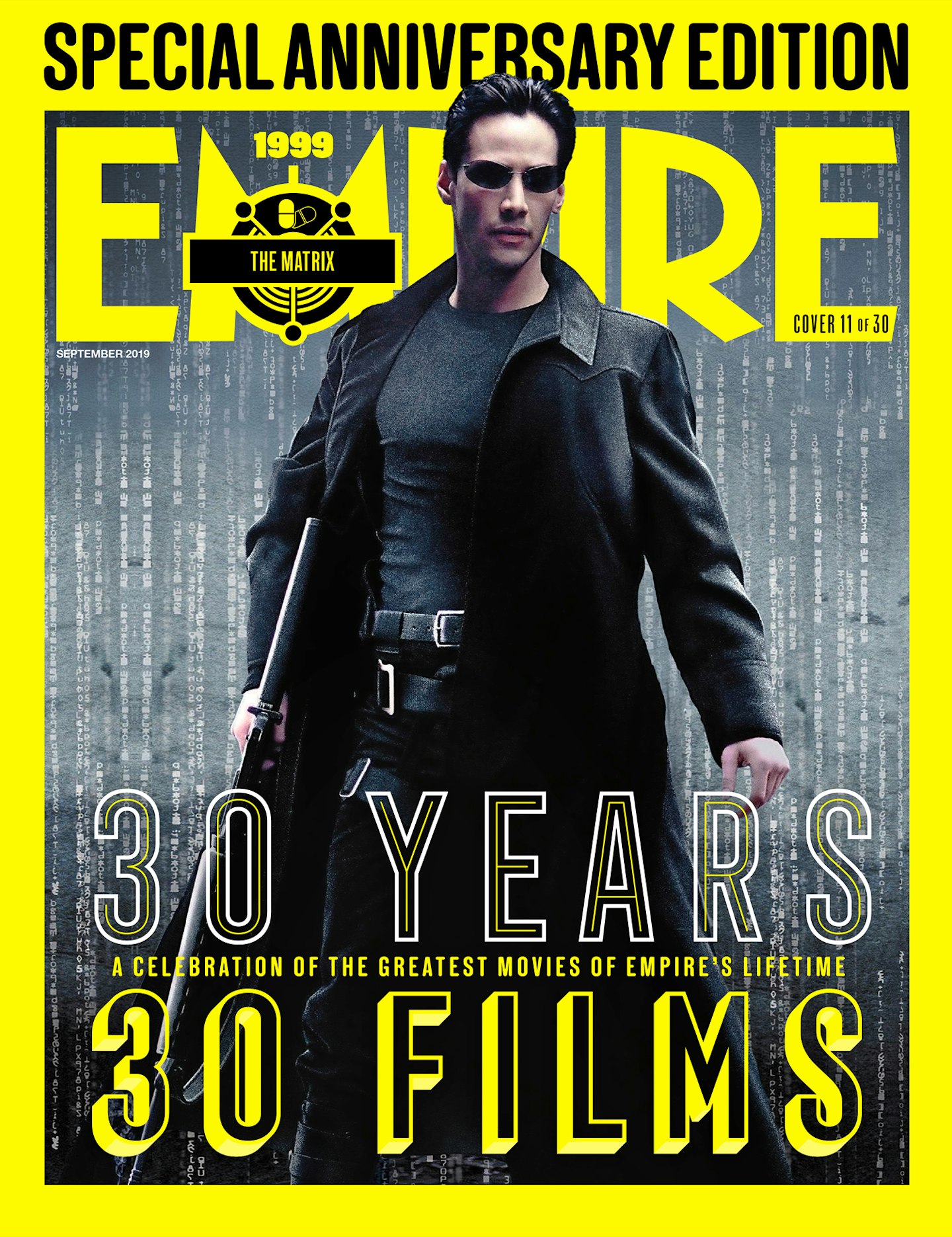

11 of 30

11 of 30#11 – The Matrix (The Wachowskis, 1999)

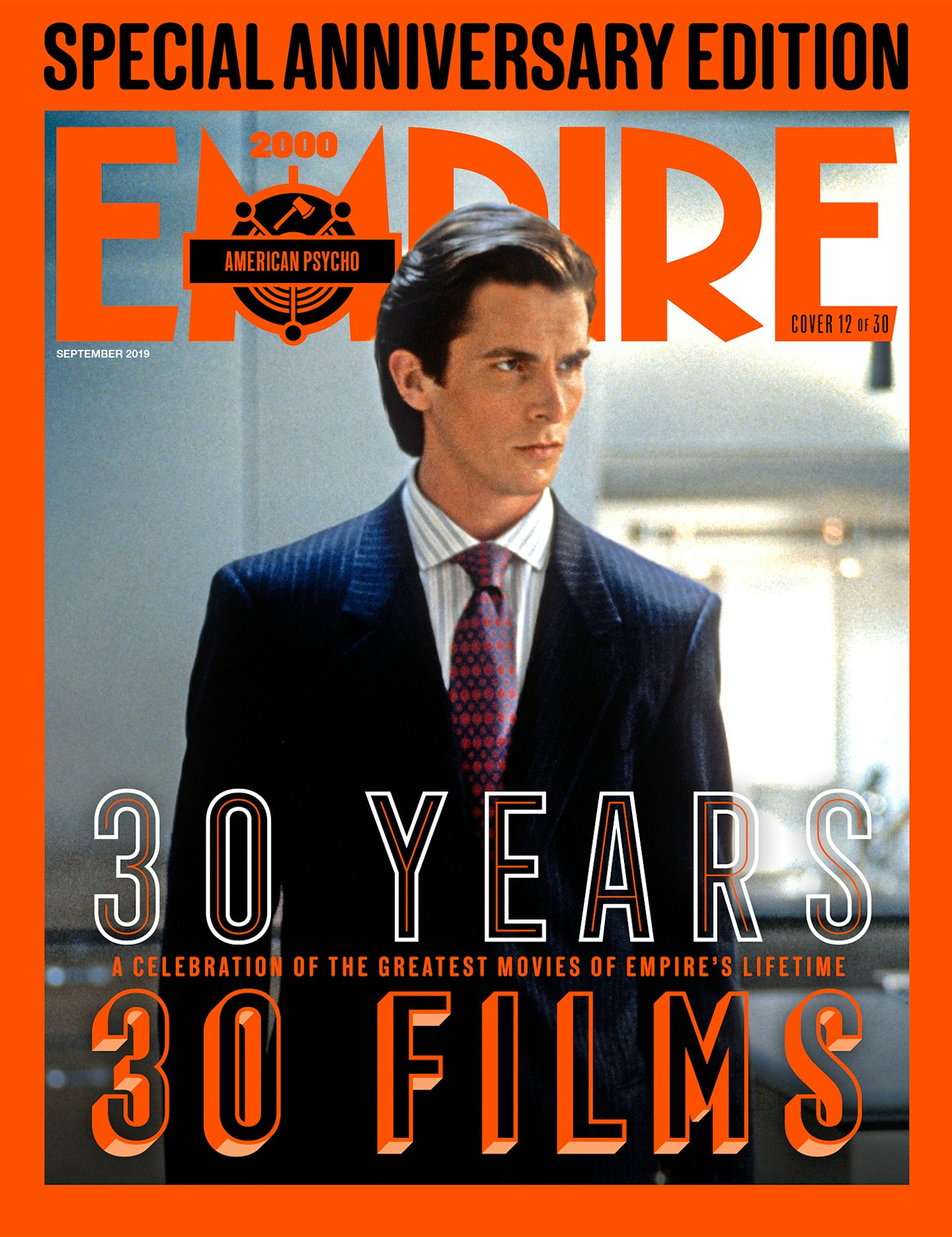

12 of 30

12 of 30#12 – American Psycho

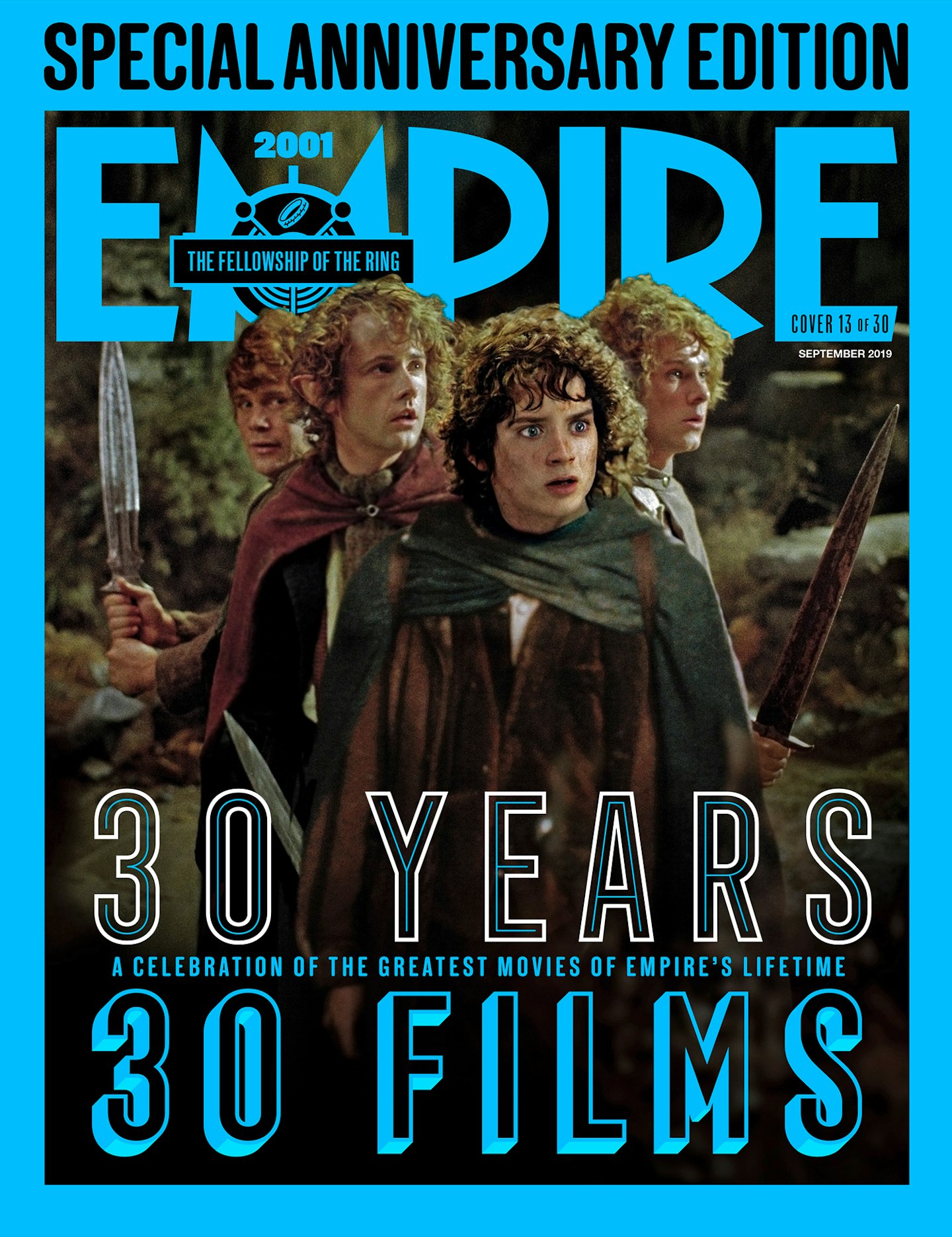

13 of 30

13 of 30#13 – The Lord Of The Rings: The Fellowship Of The Ring (Peter Jackson, 2001)

14 of 30

14 of 30#14 – Spirited Away

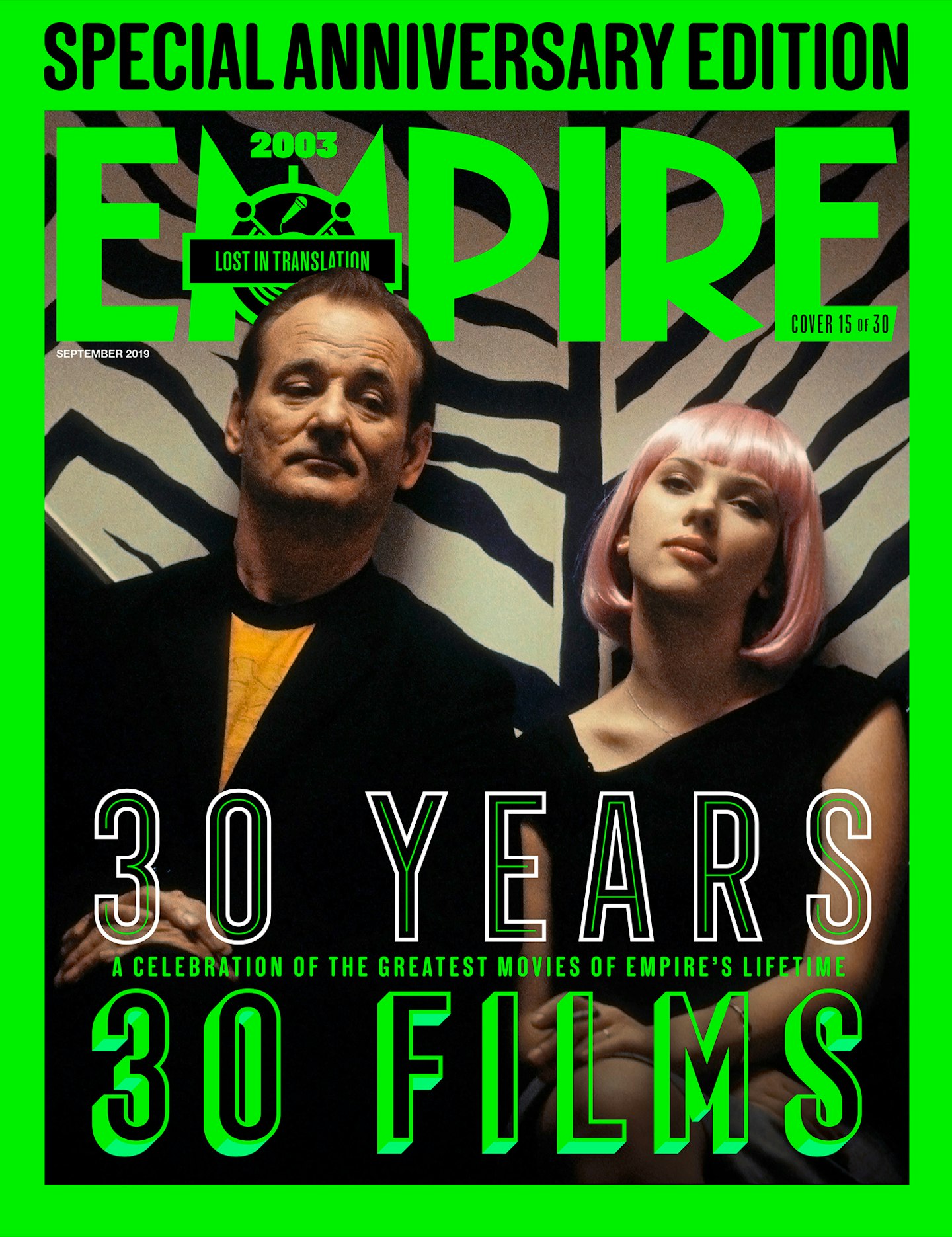

15 of 30

15 of 30#15 – Lost In Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003)

16 of 30

16 of 30#16 – Shaun Of The Dead (Edgar Wright, 2004)

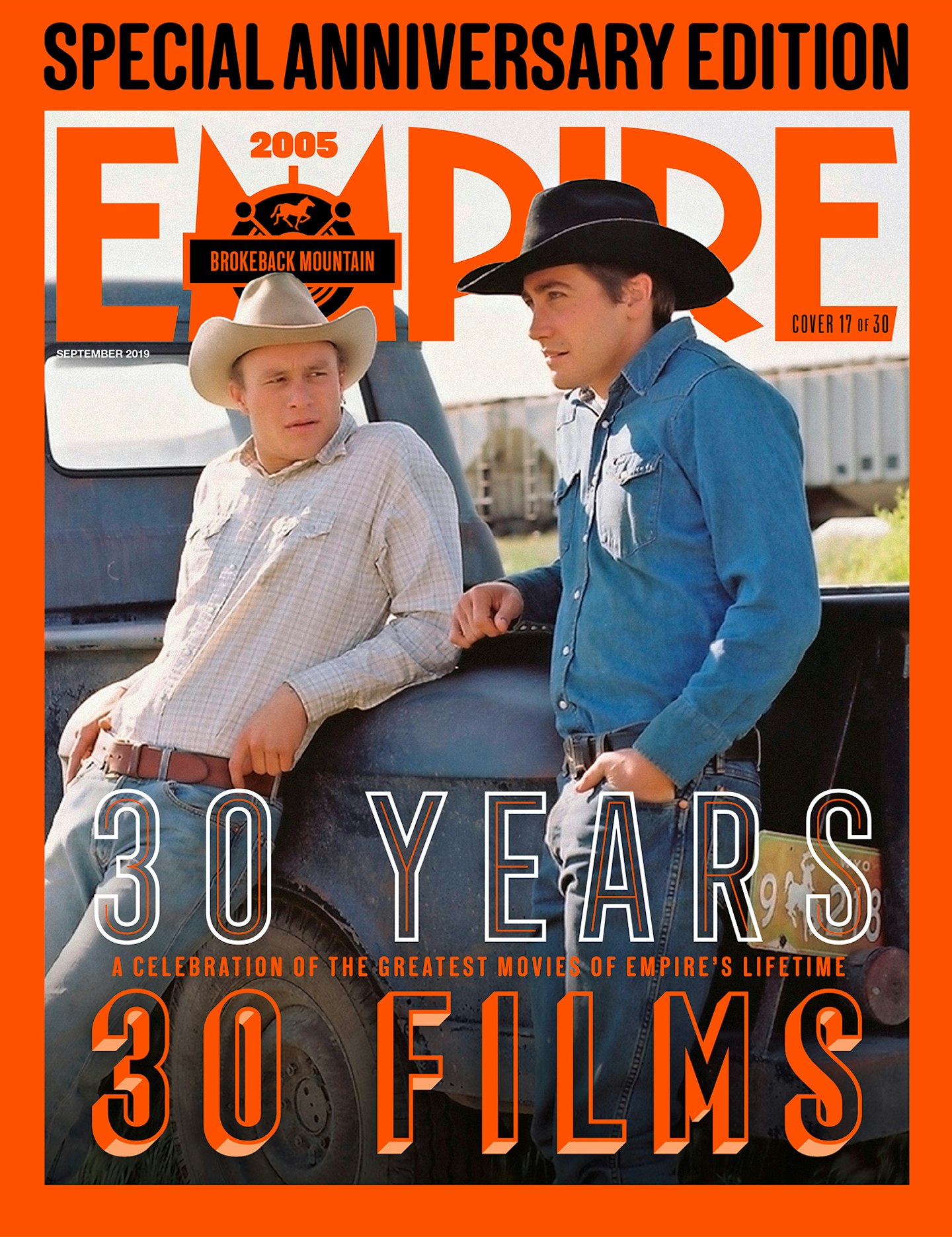

17 of 30

17 of 30#17 – Brokeback Mountain (Ang Lee, 2005)

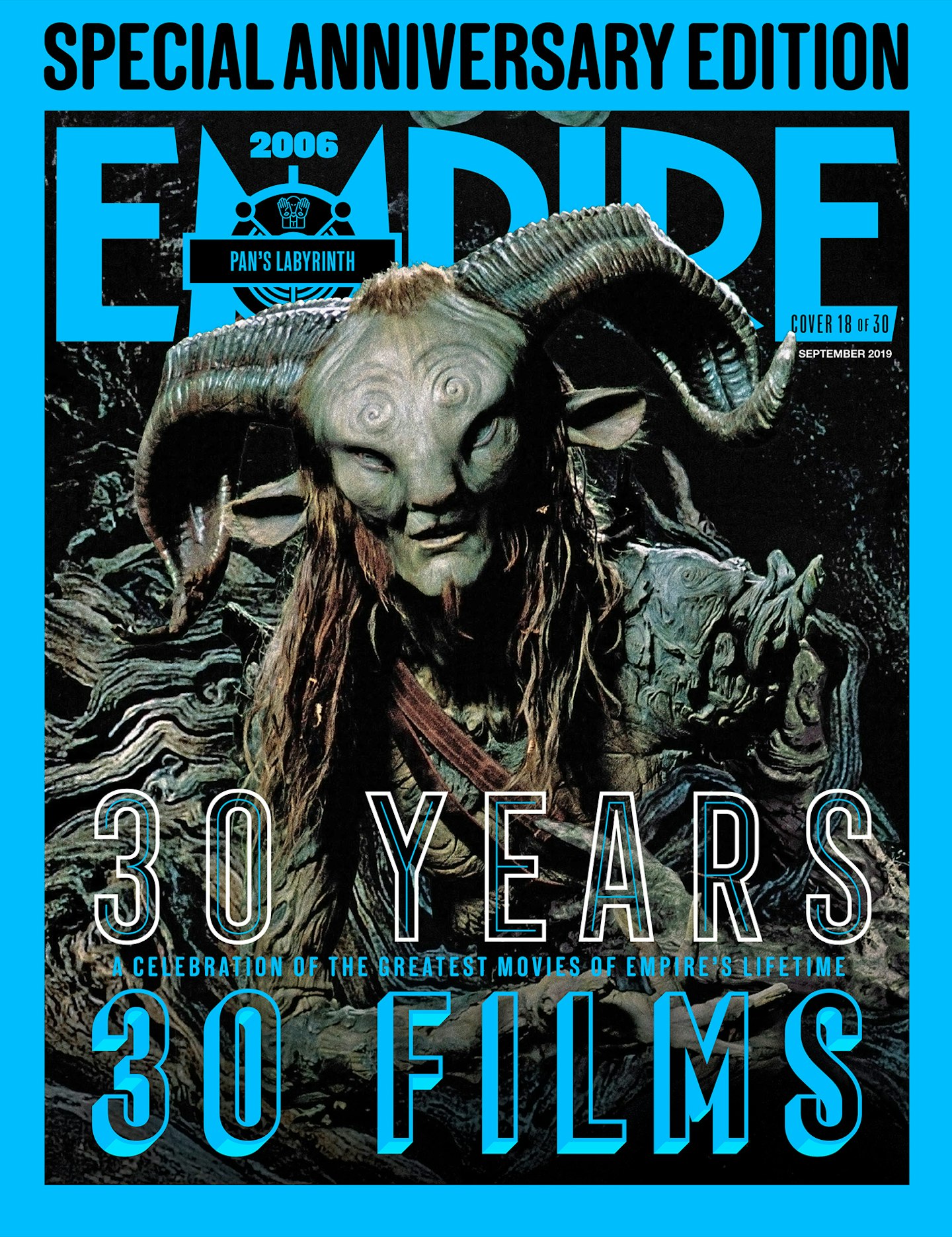

18 of 30

18 of 30#18 – Pan's Labyrinth (Guillermo del Toro, 2006)

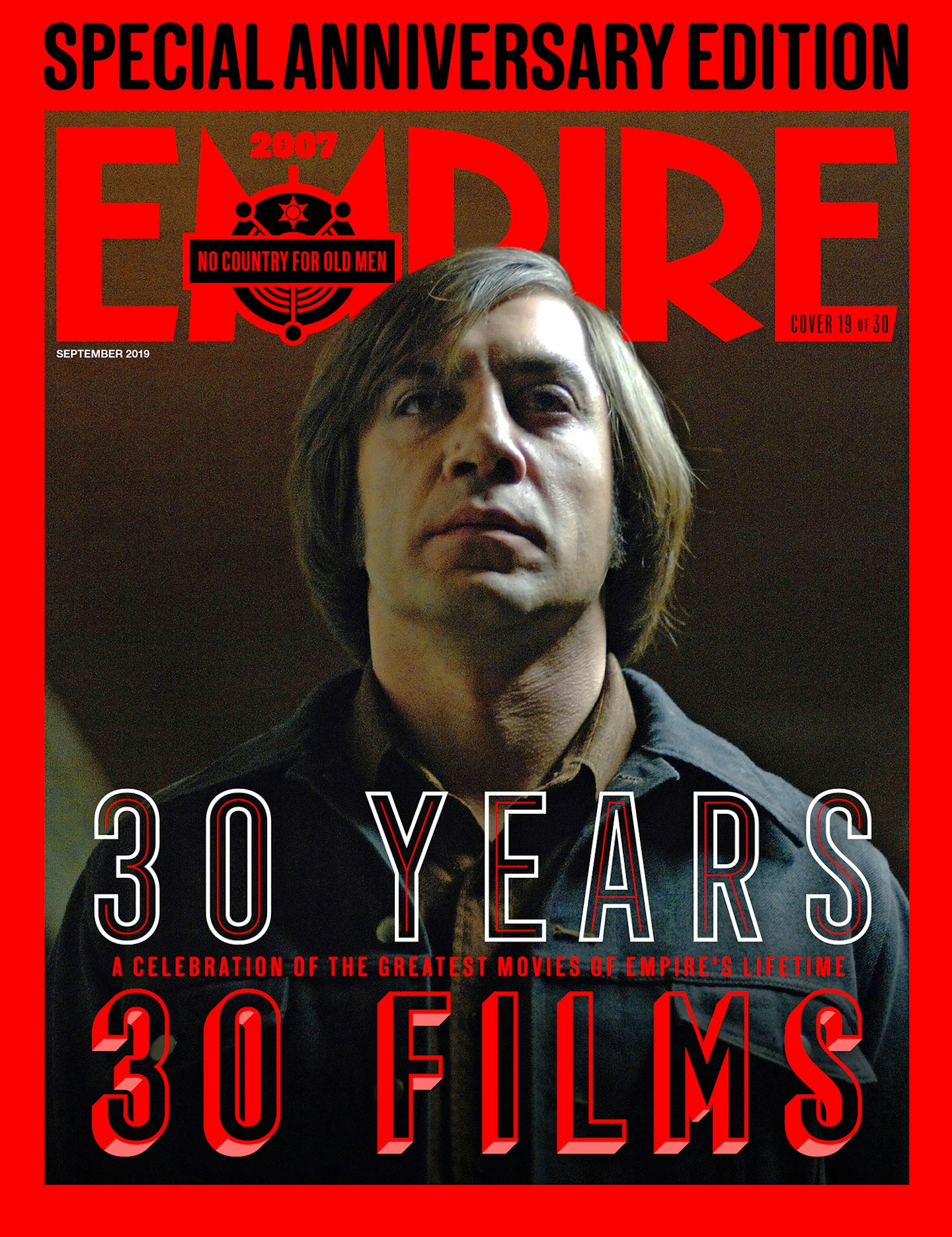

19 of 30

19 of 30#19 – No Country For Old Men (The Coen Brothers, 2007)

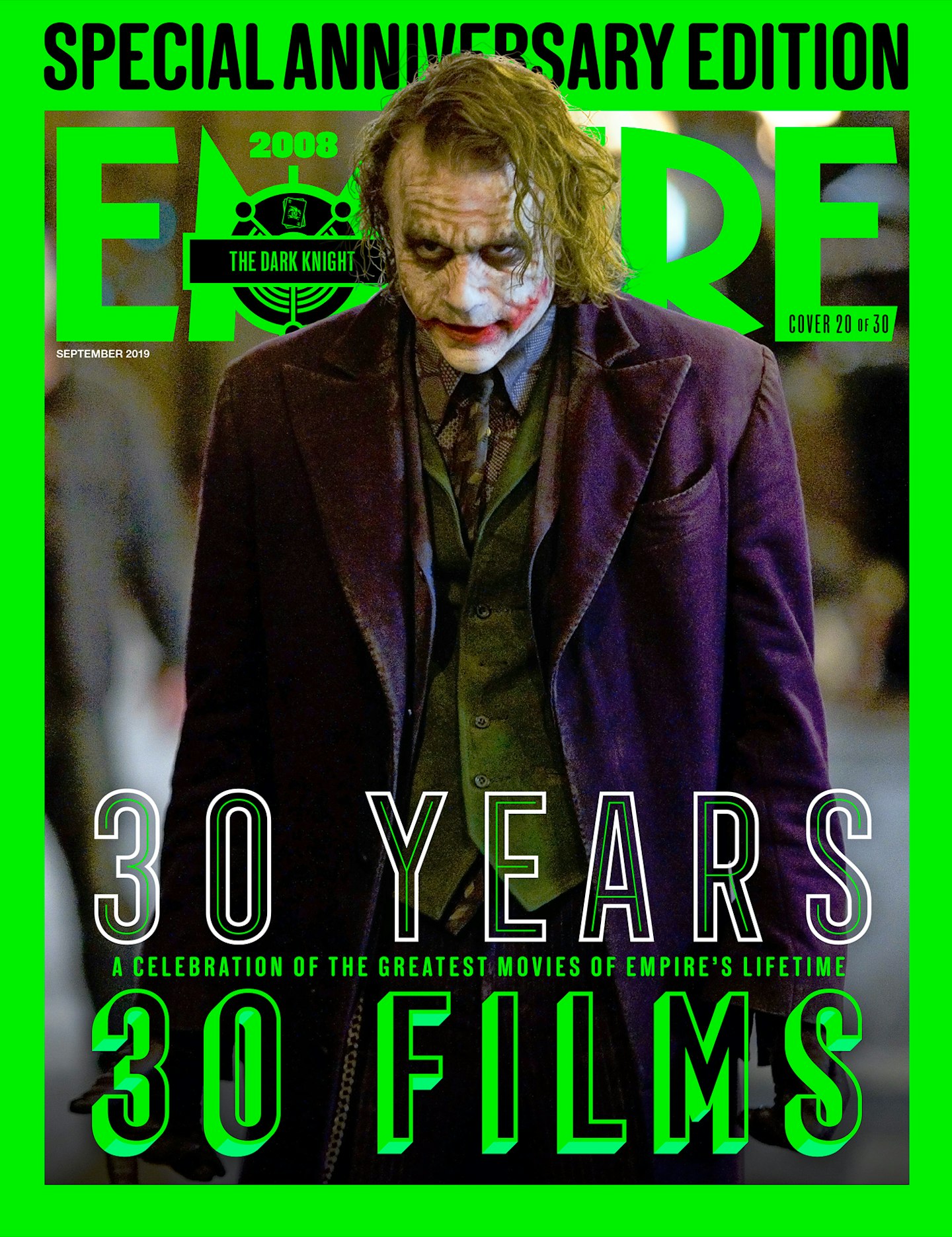

20 of 30

20 of 30#20 – The Dark Knight (Christopher Nolan, 2008)

#21 – Avatar (James Cameron, 2009)

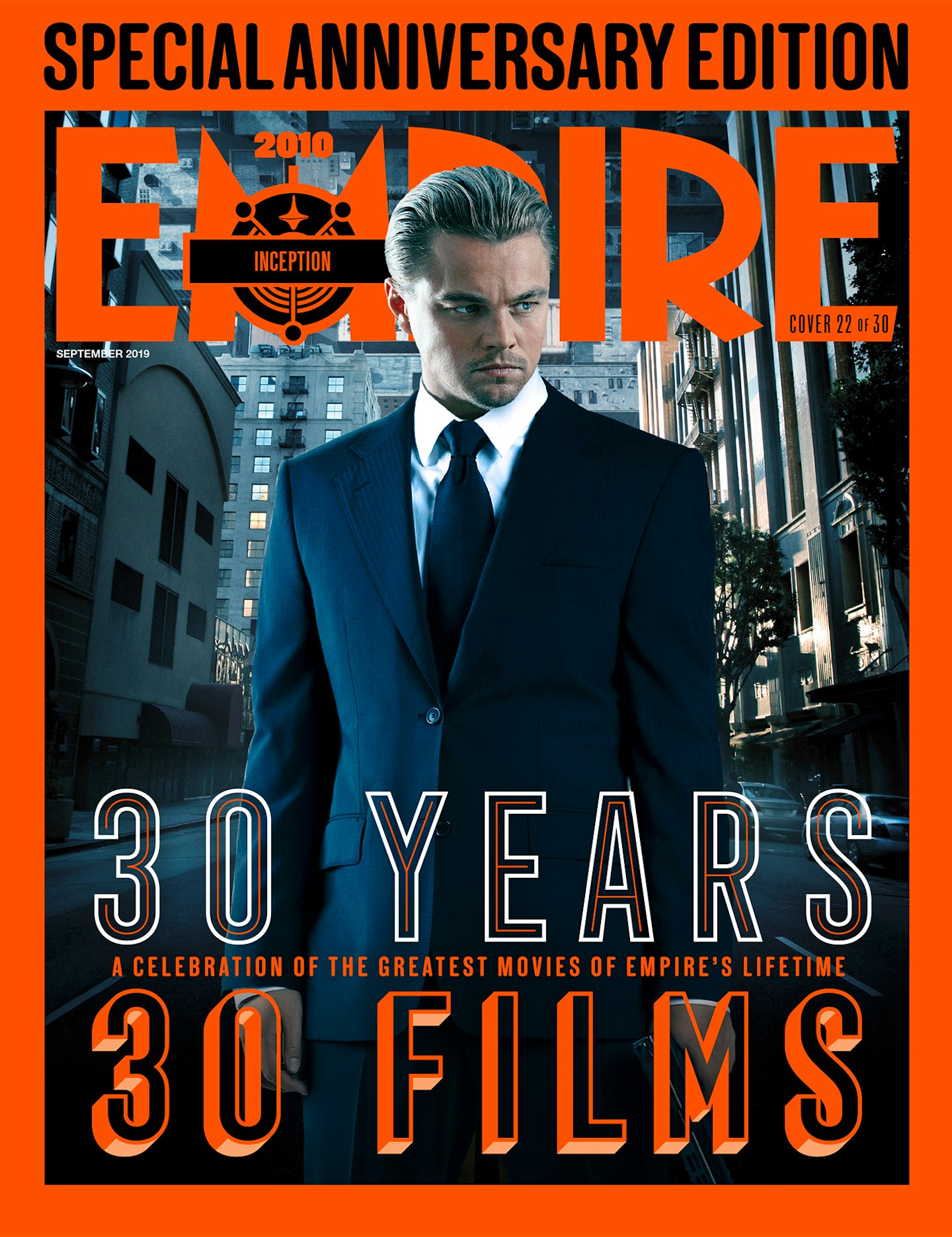

22 of 30

22 of 30#22 – Inception (Christopher Nolan, 2010)

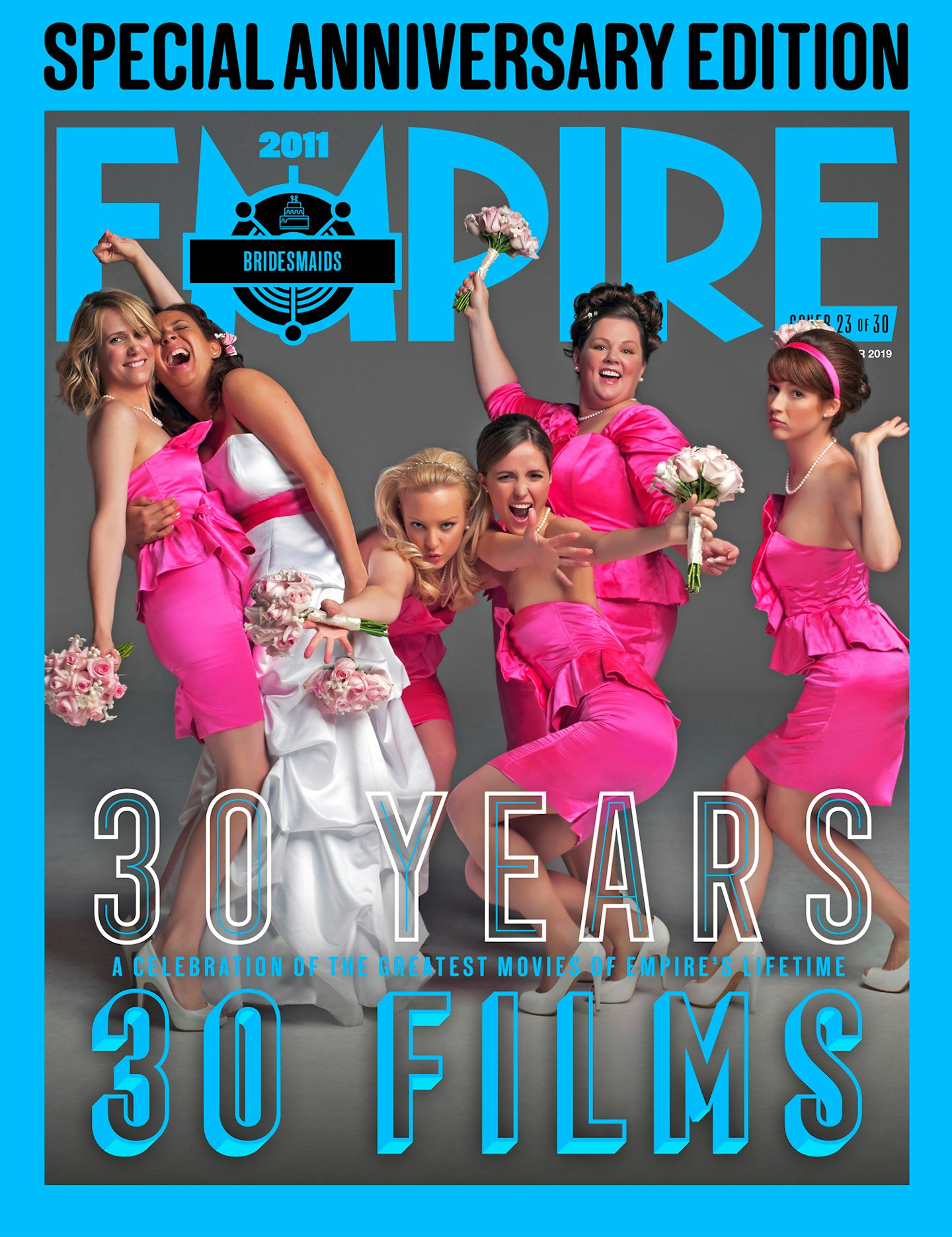

23 of 30

23 of 30#23 – Bridesmaids (Paul Feig, 2011)

24 of 30

24 of 30#24 – Avengers Assemble (Joss Whedon, 2012)

25 of 30

25 of 30#25 – Gravity (Alfonso Cuaron, 2013)

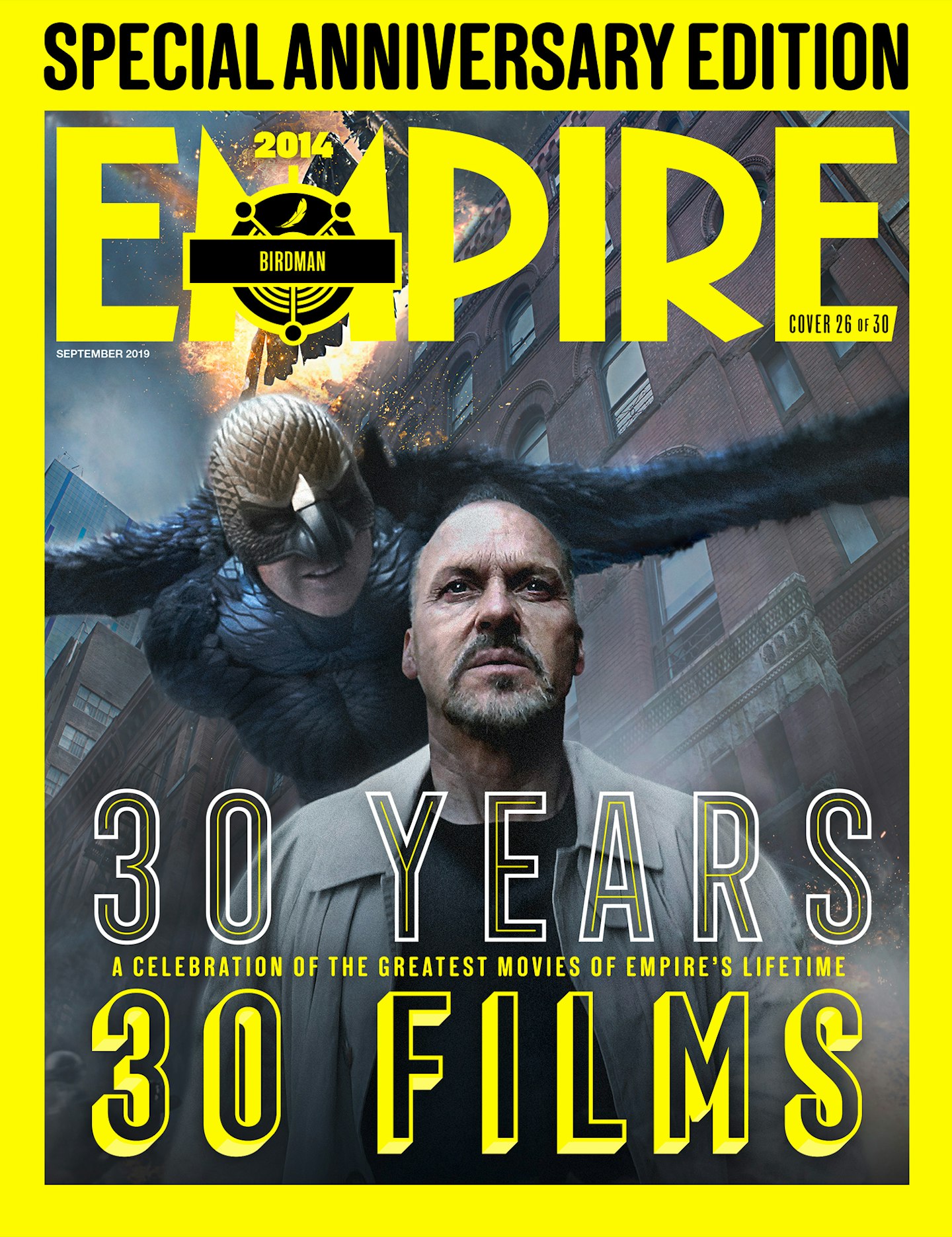

26 of 30

26 of 30#26 – Birdman (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2014)

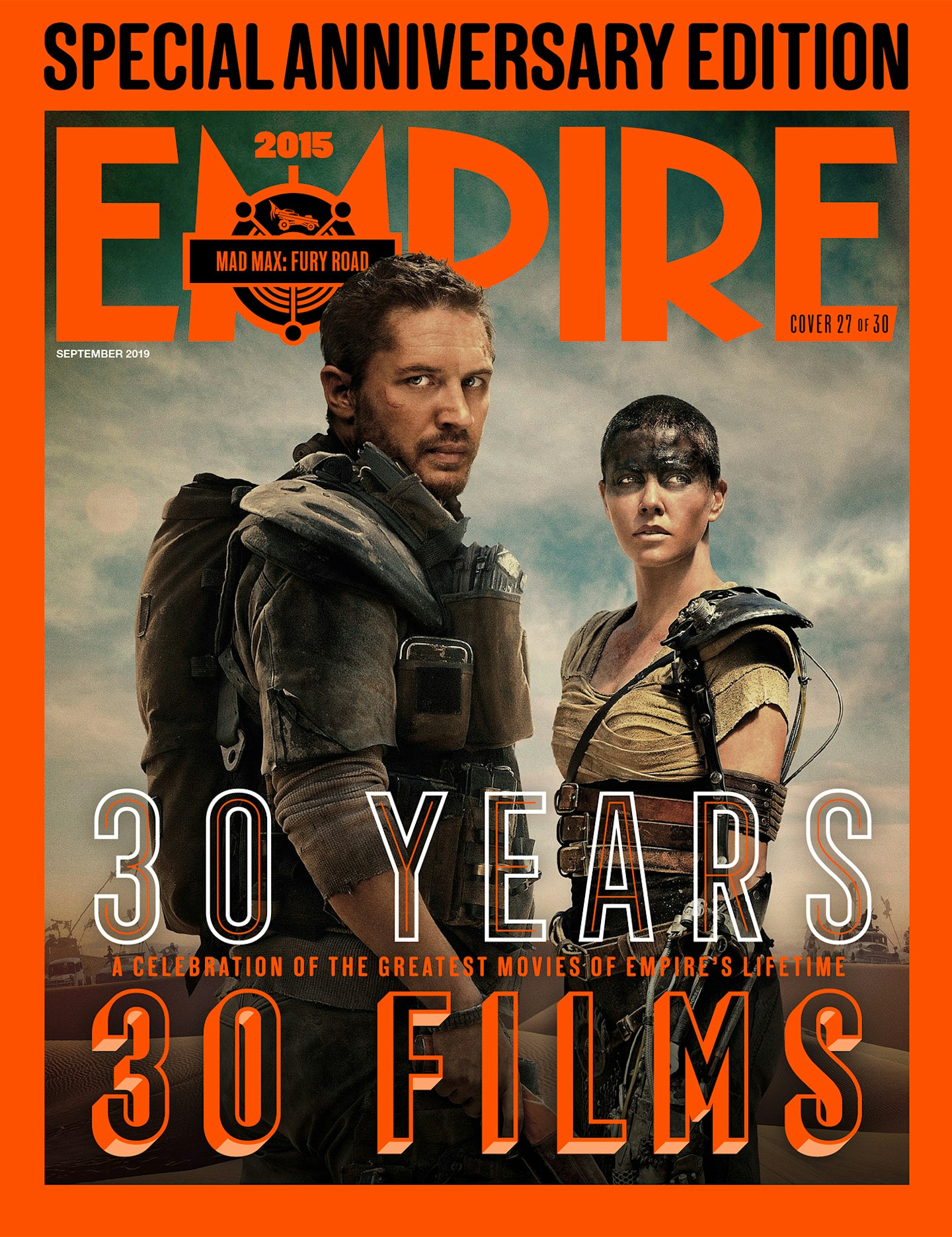

27 of 30

27 of 30#27 – Mad Max: Fury Road (George Miller, 2015)

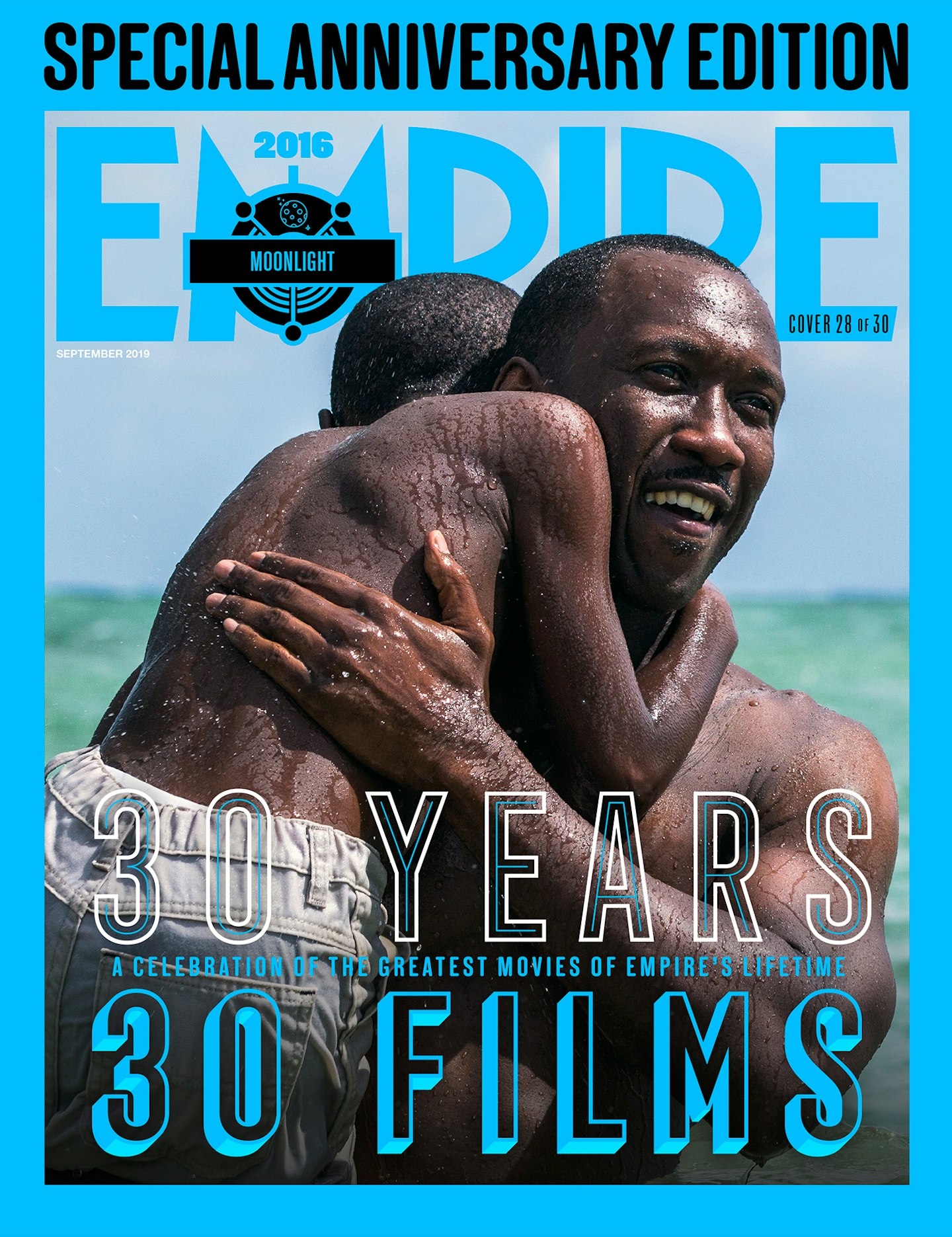

28 of 30

28 of 30#28 – Moonlight (Barry Jenkins, 2016)

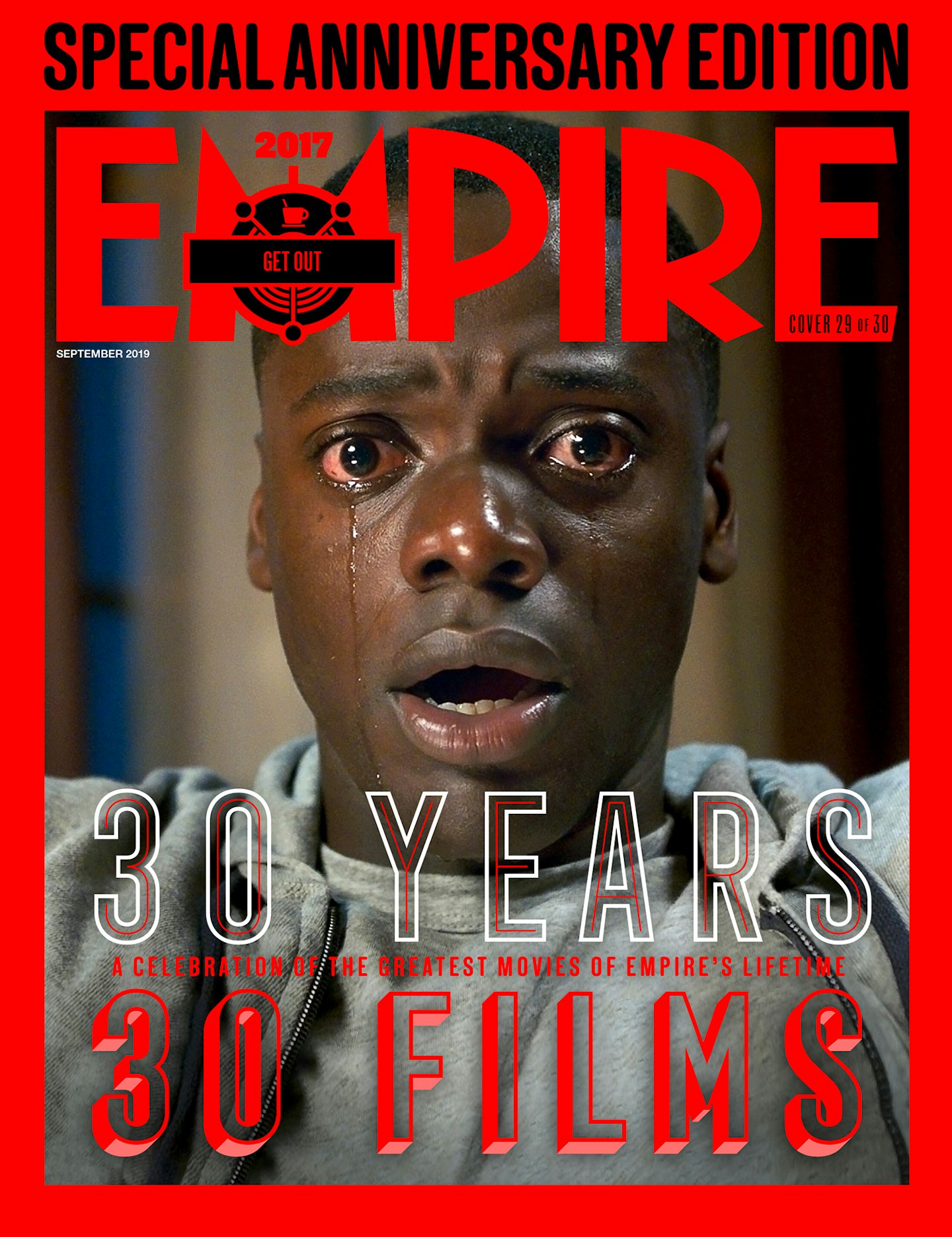

29 of 30

29 of 30#29 – Get Out (Jordan Peele, 2017)

30 of 30

30 of 30