Immortalised on celluloid as the central figure of Martin Scorsese’s GoodFellas, Henry Hill lived a cinematic life. As the gangster epic turns 30, look back at Empire’s 2010 interview with the controversial and charismatic guy who, as far back as he can remember, always wanted to be a gangster.

This article was first published in issue 255 of Empire magazine.

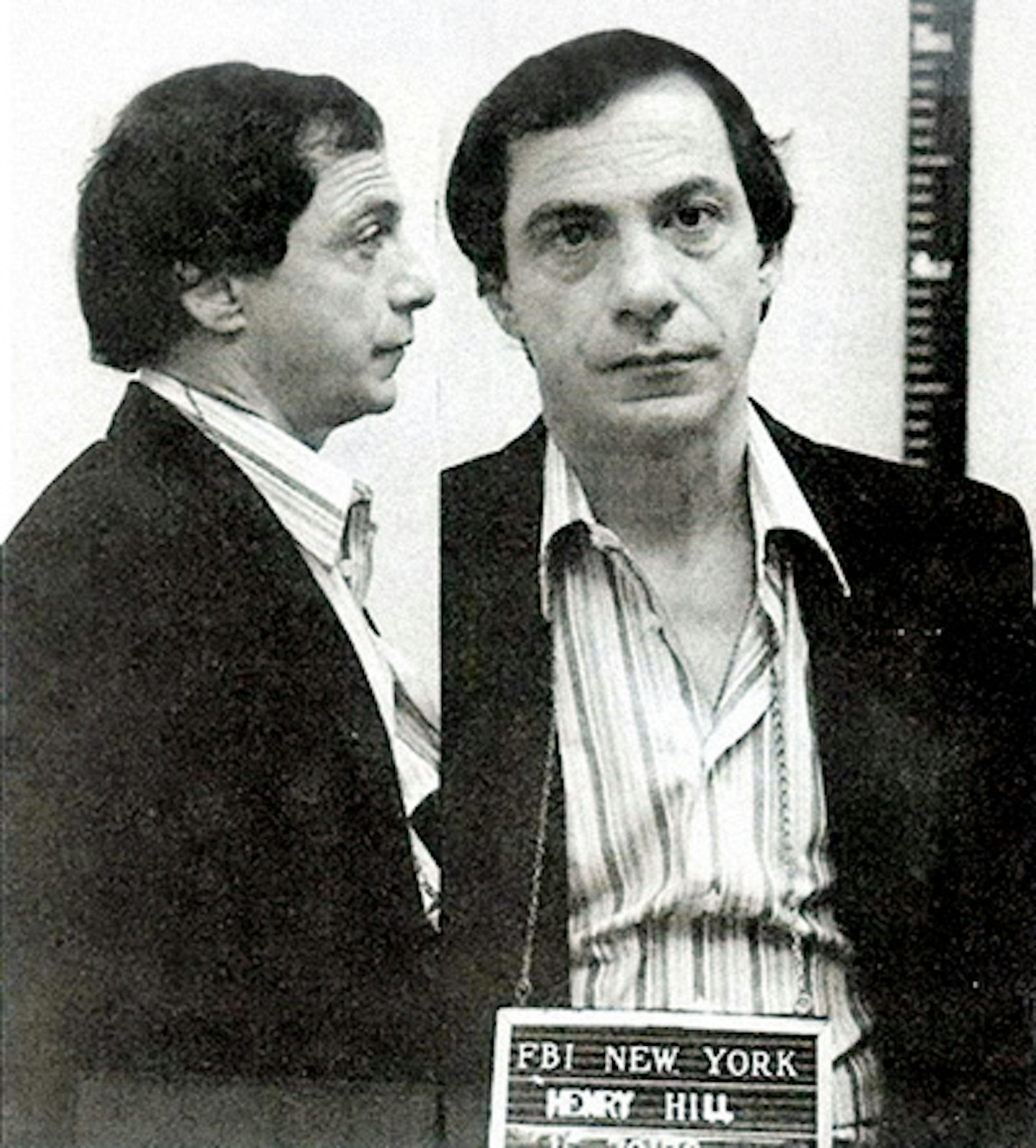

HENRY HILL IS SURPRISED TO BE ALIVE. He’s survived the Mafia, heroin addiction and alcoholism. One day, sure, his organs will give up the struggle. But it will be an empty victory for Death, as Hill has mocked that skeletal angel for decades. It’s “fuckin’ 30 years” since he turned tattletale on his Mafia mates and had a price put on his head. And it’s 20 years since he became the American underworld’s most famous footsoldier, thanks to Martin Scorsese’s GoodFellas. Now, on the cusp of his 67th birthday, Hill sits on the porch of his California home, shaded from the sun, smoking red-label Rave cigarettes and wondering how the hell he is still here. “Who’d a thunk it?” He laughs. “Who’d a thunk it?”

These days, his old conspirators can’t hurt him. Everyone he ran with is dead or in jail. Even Jimmy ‘The Gent’ Burke, the friend, partner and psychotic murderer so potently portrayed (as Jimmy Conway) by Robert De Niro, is gone. The threat comes not from a man who died (of cancer, in prison) in 1996, but from one who passed in 1911: a Mr. Jack Daniel. “I love it! Fuck it... Me and you could put a bottle away in two hours. But I’ll suffer for three days...”

There is no bourbon here today. Lisa Caserta, Hill’s manager and fiancée, is keeping him off the sauce (“Don’t give him nothing!”). Later, if he can swing it, Hill will head to a local bar or a friend’s house to watch the Lakers in the basketball play-offs. A few beers, maybe... It’s been a while since he hit it hard. Even then, he would claim he’s not as bad as he once was. “I don’t get sloppy-assed drunk like I used to, you know what I mean?” he says, in his Brooklyn rasp. “I used to fuckin’ fall down, stumblin’ ass drunk. But I can’t... I don’t come home drunk.” Caserta chips in, her voice heavy with sarcasm: “Oh, it’s been a couple of months, so guess what? That means he’s sober!” She has designated one room a “drunk tank”, where he’s banished to if he comes home insensible. Sometimes, when he’s been drinking and riding buses, she’ll get a call at an ungodly hour. A veteran of Alcoholics Anonymous, sober herself for 29 years, she then provides roadside assistance usually associated with a different AA. “She picks me up in the weirdest places, you know?” says Hill. “‘How the fuck did you get here?’ ‘I don’t know!’”

Of the many words used to describe Henry Hill — gangster, rat, thief, thug, philanderer — perhaps the most apt is ‘addict’. Whether it’s the thrill of a score, a snort, a lie or a lay, Hill has hankered after it. “Oh, man, you know, I was strung out on every single drug that’s humanly possible.” He pauses, to correct himself. “I never was into acid too much. I did acid, but I was never into it much. But every other drug...” He shrugs. “I don’t know what it is. I’m an addict! An alcoholic! If I don’t feel like drinking it’s because, like I say, I don’t want to pay the consequence. I go to a doctor once, twice a month sometimes. They check me out. They can’t believe I’m alive.” He laughs that cigarette-ripened laugh again. “The fuckin’ doctors can’t believe I’m alive!” He looks better than he should. Wiry and worn, about 5’ 8”, he has a few liver spots, his grey goatee nicotine-stained, but he could pass for distinguished or down ’n’ out, depending on the day and dress.

Other words you could use to describe Henry Hill: funny, beguiling... mischievous. This is a man who can’t believe his luck, good and bad. He’s forever been on the make, forever had an eye for an angle. Ray Liotta may have been bigger, but it’s clear what Scorsese saw in him, as the actor ably captured Hill’s sideways glances, shiftiness and defining, charming, caught-in-the-cookie-jar grin. Adapted from Wiseguy — the Hill memoirs penned by Nicholas Pileggi — GoodFellas closes with him bemoaning the grey world of the Witness Protection Program. Truth is, though, life as a “schnook” didn’t last very long. Hill never completely escaped crime, just as he could never completely escape himself. “I tried to become normal,” he says. “I didn’t know what the fuck normal was. I had no fuckin’ clue.” His troubles with drugs and drink continued, and his tendency to reveal his identity when sloshed meant he was kicked out of the WPP by 1982, a mere two years after enrolling. Still a valuable asset, he was supported by the FBI and continually debriefed, as case after case relied upon his testimony. In 1987, though, he took the stand not as a witness, but as a perp. “I got arrested for drugs.” He sighs.Twenty-three years later and he still exudes a sense of injustice. “I was using drugs,” he says, as if affronted by the suggestion he was dealing again. “But I owed one guy $9,000 and he brought in 50 keys of coke from Peru. He wanted me to help him move it. ‘Henry, you gotta help me, I did you so many favours... blah blah blah.’ So like a jerk I started introducing him to different dealers and they wheeled in a goddamn DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) agent. They said he wanted two kilos. There was something about him, I knew the guy was a cop, I knew it. But he was snorting fuckin’ lines like I couldn’t believe. I thought, ‘This guy can’t be a fuckin’ agent!’ But sure enough, the motherfucker was a fuckin’ agent, you know?”

According to Hill, his fame — or notoriety — had brought him unwanted attention: he says he wasn’t the original subject of the investigation, but the DEA switched targets when they realised who he was. Wiseguy, recounting his Mob exploits, including drug distribution, was a bestseller at the time. “The fuckin’ jurors were reading it. I mean, come on!” They found him guilty of “narcotics-related” charges and his federal pay day was over: the government had had enough. Still, whether through sweet-talking, luck or because of past services rendered, he only got five years’ probation. Fame was a double-edged sword — one he might now live by...

GoodFellas changed everything... and nothing. Scorsese and Warner Bros. paid $500,000 for the screen rights to Hill’s memoir. “That was the beginning of the Hollywood bullshit, you know?” It was probably his biggest pay day since the Lufthansa heist and he could, at least, ask for the money without fear of being shot, stabbed or garrotted. (Hill says Burke never paid him his share of the notorious airport robbery detailed in the film. He was just grateful to be left alive.)

It was his gateway into Hollywood: the chance to rub shoulders with stars again, as he had at the Copacabana, back in the day (Hill still taps his cigarettes into an ashtray bearing the brand of the famous New York nightclub). He knew Scorsese’s work. “I’d seen Mean Streets three or four times. In fact, I took Paulie to see Mean Streets!” Paul Vario — renamed Cicero on screen — was a capo in the Lucchese Family, Henry’s boss, played with heavy-lidded menace by Paul Sorvino. “But he liked the cowboy movies,” says Hill. “He’d always root for the bad guys. He liked the shoot-’em-ups. John Waynes and shit.” Now Hill was taking daily calls from Mean Streets star De Niro. “He wouldn’t even do a scene without talking to me. ‘How did Jimmy hold his cigarette? How did Jimmy hold his shot glass? How many drinks did Jimmy have before he went a little fuckin’ crazy?’”

But Hill’s homelife had fallen apart. Finally, he and his long-suffering wife, Karen (immortalised by Lorraine Bracco), went their separate ways, with her tired of his serial philandering and ongoing addictions. His two children grown, he soon had another son, with his mistress. But it would be another couple of decades before he and Karen officially divorced. “Because she thought I’d come home!” says Hill. He laughs. “She still thinks I’ll come home!” The pair spoke a couple of days ago. They live nearly 3,000 miles apart, yet clearly remain close. She really loved him.

“She still loves me,” says Hill. And for the only moment during our afternoon together, he is still, soft, a little sad. Does he still love her? He looks up and says, quietly, “Of course.” There is a long pause. Then

— laughter. “But I wouldn’t go back with her!” Hill is a proud parent, though he doesn’t claim to be a good one. “I was a fuck of a father, you know? I mean, I wasn’t a great father... But, ah, I, I know my family loves me. They tell me that every time I speak to them.” Ironically, his eldest son is a lawyer. His daughter has just given birth. His youngest is at university. None can carry his name. The threat of being whacked may have abated, but inherited reputations can be hard to kill. These days, Hill isn’t concerned about being whacked. “I know where the wiseguys hang out in LA. And the Feds tell me: ‘If I were you, I’d stay out of this place.’ I know where not to go. But all the people of my era, that I testified against, are gone, you know what I mean? There’s nobody from my pool left. Nobody has a beef with me.”

“No. They got him for murder,” says Hill, thinking back. “Oh, first they got him for point-shaving. Then they got him for murder.” He looks up, ready for another question.

Which murder was that?

“Er, ah, the murder of...” Hill lights another cigarette, buying time to remember — then forgetting about it. He laughs. “Which murder? That’s a good one! He whacked about 50, 60 people. He was a homicidal maniac! All of them were, every fuckin’ one of my partners or, you know, my associates — they were all sociopaths. To the core. They had no conscience; none of them. I mean, Tommy (‘Two-Gun’ DeSimone, played by Joe Pesci as Tommy DeVito) killed his own brother! I mean, that’s how fuckin’ rotten these motherfuckers were! Believe me, it would have been nothing for them to take my kids and lock them in a refrigerator and drop it in Jamaica Bay, you know what I mean?”

Although he cops to violence and theft and all sorts of “nefarious shit... everything but treason!”, Hill denies ever killing anyone. He did once admit murder, to US radio host Howard Stern, but his ‘confession’ (which you can hear on YouTube) consisted of one line, with reference to stabbing someone with an ice pick — “It goes in easy and it comes out easy” — and it was procured on the promise of a drink. And he did sound desperate, desperate for a drink.

“Oh, that was just to fuck with him,” says Hill now. “Me and Howard are pretty friendly, you know? He knows I never whacked nobody.” He coughs. “It’s good radio, that’s all.”

This is the curious existence of Henry Hill: a man who once had to hide now has to promote himself, extend his 15 minutes, to raise a buck. So, he makes an admission — whether fact or fiction — most should blanch at. And, regardless of whether it was true or not, it’s accurate to say he makes a living remembering and recounting things most of us would pay to forget. But, you know, it “keeps a roof over our heads”.

It was Caserta who saw the potential for Hill to exploit himself. When they met (in the early Noughties — both are fuzzy on the date), he was pretty much wrecked. “I’ve owned a couple of ranches. And restaurants,” he says. “But I always seem to fuck it up, you know what I mean? I used to be a hump, a degenerate: I’d bet on any fuckin’ thing, I’d bet on two cockroaches running across the floor... That’s why I’m fuckin’ painting these paintings now.” The paintings are scenes or riffs on his life. In his front room, with its shelves full of books, CDs, DVDs and memorabilia — from a signed GoodFellas cast photo to a cardboard cutout of Elvis — is the desk where he creates. Caserta got him lessons, got him the paint, then set about selling them on eBay.

She met him when he stumbled into her shop one day. They got chatting. She recognised his name. They became friends. Then, one Thanksgiving, she invited him over — and he never left. She tried to keep a handle on his drinking and also started arranging appearances for him at clubs, where he would give talks and sign autographs. She used to sell second-hand celebrity cars. Then, next thing, she says, “I was selling Henry. It was like the same concept.” This might seem cynical except, living in her house, cared for by her, managed by her, kept as close to the straight ’n’ narrow as he is ever going to be kept, Hill seems content. As for Caserta, a buxom, Italian-American matriarch, clearly smart, clearly strong, well... you don’t stay with an inveterate drinker unless there is love.

As well as the paintings, Hill is working on selling his own Italian cooking sauce — “It’s going to be in gourmet stores soon” — and already has his own ‘GoodFellas Coffee’. The pack he hands over is branded ‘F**K YOU, PAY ME ESPRESSO’, after the attitude of the Mob, as expressed by Hill through Liotta’s GoodFellas voiceover (“Business bad? Fuck you, pay me. Oh, you had a fire? Fuck you, pay me. Place got hit by lightning, huh? Fuck you, pay me”).

Selling coffee, paintings, himself... Hill wishes he’d saved some of the money he made over the years. “If I ever thought I would live to 67, I’d have taken two cents out of every dollar that went through my fuckin’ hands!” Still, his house is pleasant, homey, perched high on a hillside west of Hollywood, on a quiet street in what was originally intended as a retirement community. A compact garden circles the bungalow, while a pond nestles just beyond the two pots — full of butts and fag packets — that flank the stoop where we sit. The view is spectacular. There are two BMWs parked out front, under an awning. And a neighbouring house is on the market for nearly $400,000. So, you know, the goodfella ain’t doing bad.

When he’s not on the road, he likes to cook, to read, to fish, to “bullshit on the phone with old friends”. After sundry busts, he’s now been clean of illegal drugs, he says, for seven or eight years. No more heroin. Now he’s a “news junkie”, and his syringe of choice is CNN. “If I had $16 million in the bank, I don’t know if I’d be living any better than I am now, you know?”

Still, you can sometimes hear the little twinges, memories, of living the high life. Asked if he thinks there’s a danger GoodFellas glamorises gangland, he talks of telling youngsters about the dangers of crime, but soon segues into what sounds like affectionate reminiscence. “I like to talk to kids who aspire to that life... I have kids come up to me and say, ‘Henry, I seen that movie and it changed my fuckin’ life! I straightened the fuck out!’ So I don’t think the movie glorifies that kind of life...” He pauses. “I mean, listen, the life was intoxicating. The good times — which was most of the time — it was great, you know? We got treated special in New York. Everybody knew us. And they knew about us and they didn’t fuck with us. They rolled out the fuckin’ red carpet. When doctors, lawyers, judges had to stand in a fuckin’ line, we never stood in a fuckin’ line. And we always tipped well. We took care of everybody. Money was like confetti back in those days for us...”

Half-Irish, half-Sicilian, Hill wanted to be a gangster, yes, as far back as he can remember. And hearing him talk, you think he must miss it — but he insists he doesn’t. “Believe me, I wouldn’t want to go back to that life. And I tell these kids, ‘I’m the last of the Mohicans,’ you know? There’s no-one from my time around today. They either got whacked or got into penitentiaries. Believe me, if I had one then I had 25 opportunities to get back into shit that could’ve got me a life sentence. I just go, ‘Man, get the fuck away from me!’”He’s a survivor, then, Henry Hill. A pragmatist, a charmer — he did what he had to do, because the alternative was life inside or no life at all. When he says, “I couldn’t forgive myself,” he’s not talking about the crime, he’s talking about the confession, about turning on his collaborators. “Because there was a time when I would have put a fuckin’ gun in my mouth and blown my brains out rather than testify against these fuckin’ people. It was a process for me to forgive myself for being an informant, a rat, you know?”

He still sometimes gets flashbacks to the “horrific shit I’ve seen in my time”. He says he’s “spiritual”, that he prays every day to the Virgin Mary (he re-converted to Catholicism, having taken up Judaism for Karen). “I absolutely believe in God,” he says. “I believe that’s the reason I’m on this fuckin’ Earth today. I mean, I shouldn’t be around. Number one: I must have OD’d a half a dozen times in my life — like, just flatline. ’Cause I have such a tolerance for drugs, I can do an enormous amount! I used to be able to drink that way, too, you know? And when I drank I could even drink more, you know? When I used coke and shit. And then I started slamming that shit.”

From spirituality to the spirit to slamming that shit (one of the few things Scorsese changed from page to screen was that Hill eventually dealt in heroin, rather than cocaine)... It’s a journey Hill’s answers often take: from the present reality of what is good for him, to reflecting with relish on what was bad. “I try to be a little bit better today than I was yesterday,” he says. “Listen, if I don’t pay my dues, I’ll wind up with the rest of those guys... [in Hell].” Death, he says, doesn’t bother him now. “Hey, I’m going to get what I got coming, no matter what.” When he’s gone, he figures he’ll be remembered “as the guy in a movie, you know?” And he wants everyone to have a party. “I used to say, ‘Buy a couple of ounces of coke and mix it with my ashes and get high,’” He laughs. “But that’s out! So, have a good Irish wake when I die.”

While life goes on, though, it’s appearances, paintings, talks, autographs, drinks... People often want to buy him drinks. Bottles will be sent over or shots bought. He says he sometimes says no. But he more often says yes.

“Being the alcoholic I am, sure, I’m not paying for it — fine!” He still gets in trouble occasionally, for drinking in public or drunkenness, but, “I don’t commit felonies, I commit stupid misdemeanours, you know? I know better, but when I get a few drinks in me...” He smiles. He seems resigned to his life, his nature, but not depressed. And he’s a very likable guy. Someone you’d like to go out on the town with, if your conscience would allow it.

This Friday, he intends to take a trip to Sin City, where Caserta will let him off the leash. He grins. “I’ll be hitting some Jack Daniel’s on my birthday in Vegas!” A few days ago, he was at the Spike TV Awards, where Liotta and De Niro were inducted into the ‘Guy Movie Hall Of Fame’. From the stage De Niro joked, “Henry, stay down there, I don’t want to get hit with anything meant for you!”, while the joshing of Liotta — “Be ready!” he warned the audience, as he gave a shout-out to Hill — showed a warmth not blind to past experience. Hill doesn’t often see them, but “occasionally they send a message, you know? I know where to find Ray if I have to... if I’ve got something I want to pitch or whatever!” Liotta and Pileggi have both paid for him to go through rehab before, but after multiple attempts, he doesn’t imagine he’ll ever give up alcohol. Not that, he insists, he is drinking to forget. “I don’t think so. I enjoy it! I fuckin’ enjoy it! Believe me, I don’t feel bad. I’m proud of what I done — those people I put in prison, I saved a lot of fuckin’ lives and I saved the government millions upon millions.”

He’s right. He saved lives, he saved money. Most of all, though, whichever way you cut it, Henry Hill saved himself.

--

## True Crime

Henry Hill talks us through GoodFellas' classic moments, and how far reality drove the drama...

"You had to be on edge with Tommy. He was a homicidal fuckin' maniac! He used to put notches on his fuckin' pistol and tell everybody how he tortured a motherfuckin' guy. I don't want to hear that shit, you know? I was so fucking relieved when he got killed. You ain't got no idea. You ain't got no fuckin' idea." THE DRIVEWAY BEATING (0:38:55)

"That's just how it happened... I just fuckin' busted his head wide open. They called an ambulance and cops came. I had bullets in the glove compartment and I threw them under my fuckin' car. I said, 'I didn't hit him with a gun! I hit him with a fuckin' rock or something...' They bought it." SHOOTING SPIDER (1:08:02)

"Tommy was crazy — just on impulse. Jimmy was the same fuckin’ way. He was another fuckin’ loose cannon. And he had a list. If somebody wronged him, he’d say, ‘I’m putting that cocksucker on my list, I’m going to whack that guy.’ Sure enough. It may take him six months, a year, but he whacked the motherfucker." KAREN COCKS IT (1:10:22)

"That was exactly how it happened! She cocked that fuckin' thing, she cocked that motherfucker and her hand was shaking like this and all I could see is those fuckin' bullets, you know, of this revolver, .32 snubnose. That happened just the way it happened." THE LUFTHANSA KILLINGS (1:41:47)

"I'd just got out of the can, and the Feds kept coming to my house. They'd wait for my kids to go to school then bang on the fuckin' door. They kept showing me pictures [of the bodies]: 'Henry, you're gonna be next, you gotta co-operate.' I didn't then, but they put the seed in my head."