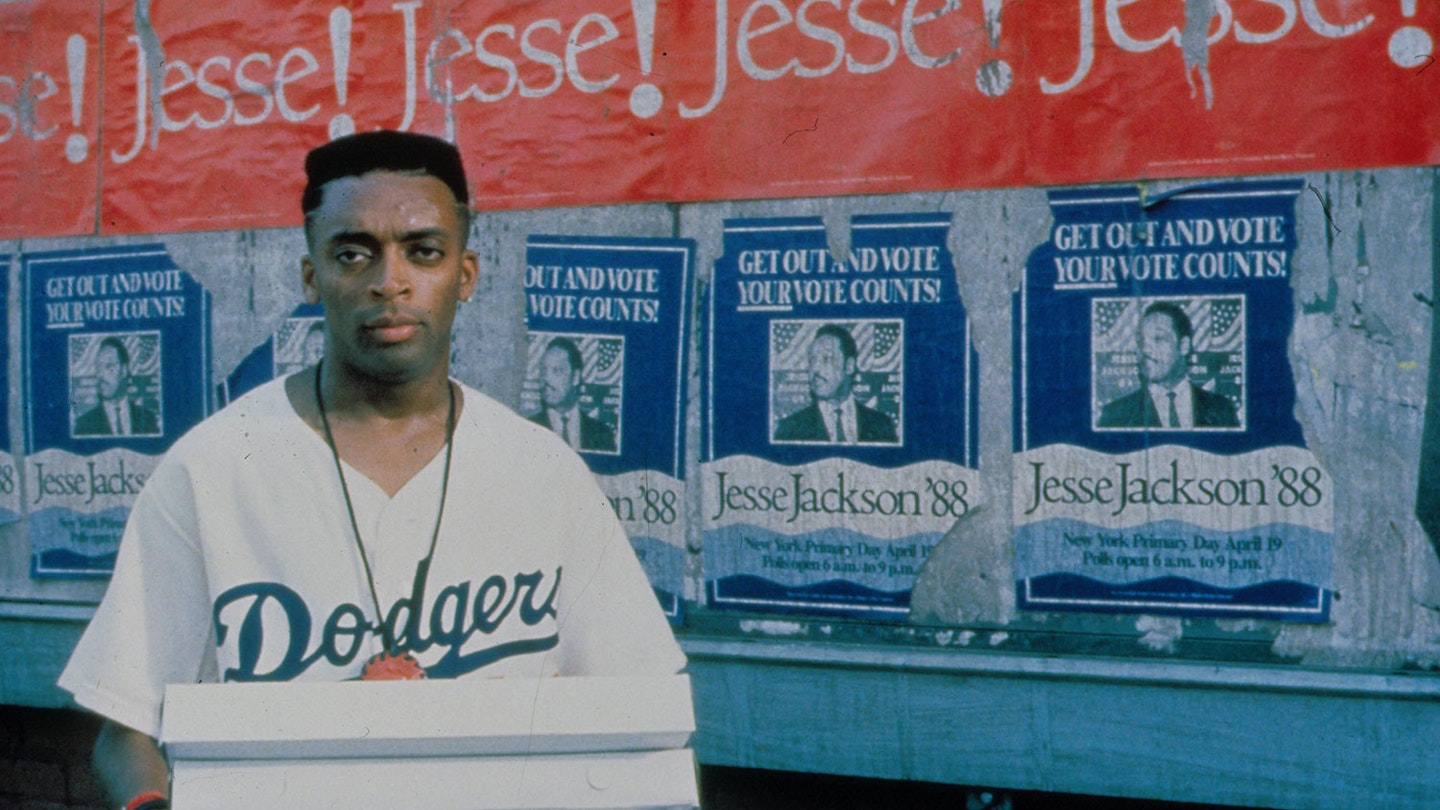

As part of our Empire 30 celebrations, we spoke to the crew behind Spike Lee’s masterpiece Do The Right Thing – including the director himself. Originally published in the October 2019 issue of Empire.

The area between Quincy Street and Lexington Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, used to be known as Stuyvesant Avenue. Today, it’s simply, and officially, known as Do The Right Thing Way. Acknowledgement not just that it was the sole shooting location for Spike Lee’s propulsive, wildly entertaining, poignant and pointed third joint, but of the movie’s immense cultural footprint. A day in the life of a collection of wild and wonderful characters as they go about their business in the midst of a heatwave, Do The Right Thing is funny, profound, profane, and eerily prophetic, as it builds towards a violent confrontation between the Italian-American owners of a local pizzeria and exasperated members of the African-American community.

Along the way it broke all kinds of cinematic rules, introduced characters as indelible as Radio Raheem, Buggin’ Out and Mister Señor Love Daddy, and gave the world, and Black America, a brand-new anthem in the form of Public Enemy’s ‘Fight The Power.’ It also confirmed Lee’s enormous talent and, more adroitly than perhaps any movie before or since, captured and commented upon America’s growing racial divide. Thirty years on, with racism and racial violence on the rise in the US, it feels like a film that could have been made yesterday. Only the absence of mobile phones in the movie roots it firmly in the late ’80s. That, and Radio Raheem’s massive boombox.

Spike Lee (Director): After 95 degrees, motherfuckers lose their mind. The murder rate goes up, everything goes up. I just had this idea of what would happen on the hottest day of the summer.

Ernest R. Dickerson (Cinematographer): I remember when Spike started writing it. We were on a plane together flying to LA to do the answer print of School Daze. He writes longhand on a yellow legal pad. The title was ‘Heatwave’.

Lee: That was a nod to Martha Reeve And The Vandellas. But Do The Right Thing was part of the language. “Do the right thing.”

Robi Reed (Casting Director): I remember him sending me the script with a postcard that said, “For your eyes only,” with a picture of eyeballs. And he signed everything, “Love deep, Spike.”

Ruth E. Carter (Costume Designer): He was very proud that he could write scripts like this in two weeks.

Lee: Ten days.

Carter: Spike was not doing things in the studio system. He would call me in California and say, “Get your ass out of Hollywood. Come back to Brooklyn, we’re going to tell the story of Do The Right Thing.”

Lee: I wanted to do a film that was about New York City at that particular time. The racial climate, the historical hostility between the African-American community and the Italian-American community. It was based on stuff that was happening. The film is dedicated to, specifically, individuals and families who are no longer here because of the NYPD.

Dickerson: I knew it was going to be dealing with a tense situation. I didn’t know where he was going with it until I read the earliest draft. It rang so true. It was in keeping with what was going on in New York at that time. It’s a microcosm of America.

Using many of his regular crew, and the odd cast member, from his previous two movies, Lee and co turned Stuyvesant Avenue into their temporary home for a couple of months.

Lee: That’s not a set. That’s one specific block.

Dickerson: I was able to help select the neighbourhood we were going to shoot it in. I demanded that we shoot on a street that runs north and south. So one side of the street is always going to be in shade. On a cloudy day, it was easier to make that look like the shaded side of a street.

John Turturro (‘Pino’): It was a funky area. But there was a lot of crack. A lot of skinny dogs.

Dickerson: The nation of Islam supplied a security force for us. They called themselves the X-Men.

Giancarlo Esposito (‘Buggin’ Out’): We got strong support from the two families that were left on the block. They were happy because the block was cleaned up. We cleaned up a couple of crack houses. We didn’t feel like heroes.

Dickerson: Just being there helped a lot. It was like having a huge movie lot there in the middle of Bed-Stuy.

Lee: The film takes place on the hottest day of the motherfucking year. I said, “I want audiences to be sweating even though the motherfucking theatre is air-conditioned.”

Dickerson: Spike said, “Hey man, I want you to start thinking about how to get the audience to feel the heat of the hottest day of the summer, visually.” The main technique I used was colour. The warmer colours have the tendency to raise the heart rate.

Lee: That red wall, where the cornermen sit, wasn’t there. It was painted that colour.

Esposito: It was hot. When we were able to open the fire hose as Frank Vincent [Charlie] drove that Cadillac down the street, those were welcome moments. I remember people used to dip washcloths in ice buckets and put them around our necks to keep us cool.

Roger Smith (‘Smiley’): It truly was the warmest August up to that time in New York City. When you saw us perspiring, it wasn’t make-up. They weren’t spraying us down. It was truly earned sweat that was happening.

Carter: We shot from hot summer to fall, so by the end we were buying blankets for people. We added the sweat. Spike was very adamant about us having bottles with glycerin and water spray bottles on set. So now it’s getting cold and we’re spritzing people down so it looks hot.

The film turns on the confrontation between Danny Aiello’s Sal, the Italian-American owner of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, and Esposito’s Buggin’ Out, who becomes enraged that Sal’s ‘Wall Of Fame’ doesn’t have any pictures of black people on it

Lee: On the wall, De Niro. Pacino. Frank Sinatra. Everybody.

Turturro: A lot of those pictures on the wall, they’re my pictures. Wynn Thomas, the production designer, asked me, “Do you have pictures?” I said, “Yeah, some good ones.” I brought in a lot. The fighting ones — Rocky Marciano is one.

Lee: My family, the Lees, were the first African-American family to move into Cobble Hill in Brooklyn. It’s a stone Italian-American neighbourhood, right by the Brooklyn Docks. I grew up amongst Italian-Americans.

Turturro: I grew up in a black neighbourhood and moved to a white neighbourhood. I grew up in Hollis, Queens. I grew up exactly the opposite of Spike.

Lee: I think that animosity between Italian-Americans and African-Americans is because we’re so alike. I knew that we had that. The pizzeria came from the New Park Pizzeria in Howard Beach, where Michael Stewart was chased out by a gang of bat-holding Italian-American teenagers. In trying to get away, he was hit by a car on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. I wanted to explore that love-hate relationship between Italian-Americans and African-Americans.

Turturro: Giancarlo is half-Italian. So when he’s having that fight it’s almost like he’s having that fight with his father. He knows who he’s talking to.

Esposito: Culturally, the movie changed my life. My father’s from Naples. I had that partly Italian heritage. And Danny and I had some very heated scenes towards the end of the movie. What came up was a lot of our own remorse, anger, frustration, and resentment for having to hold this racist attitude on both of our parts. We wound up finishing the scene for the fourth or fifth time and crying in each other’s arms.

Lee: Buggin’ Out has a point. But Danny has another point. “If you want black people on the wall, you can have your own motherfucking business and do what you want.” That makes great drama. We have two opposing viewpoints and both have validity.

The racial tension grows throughout the day, culminating in a stand-off that night which results in the brutal murder, by chokehold, of Bill Nunn’s Radio Raheem at the hands of an NYPD officer. In the aftermath, Lee’s Mookie, who’s worked for Sal for years, throws a trash can through the window of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, triggering a sequence that’s long been referred to as ‘the riot’.

Lee: Not riot. Uprising. If you look historically at the uprising that happened in America, of African-Americans, it wasn’t like black folk woke up one morning and said, “Let’s burn it down.” There’s a tipping point. The tipping point for Mookie was to see his best friend, Radio Raheem, get choked to death. I made that movie in 1989. Then to see a videotape of Eric Garner, it affected me so much I called up my editor, Barry Brown. I said, “We got to do something.” We put together this clip where we cut back and forth between Radio Raheem’s murder — fictitious — with the real murder of Eric Garner. It’s eerie how similar it is. We put it up on the internet.

Smith: At the recent block party for the film in Bed-Stuy, a young family came up to me. Eric Garner’s family. They were very moved that he had been mentioned within the context. The pain of that loss was very tangible.

Lee: It made people think, “How much have we progressed?”

Shooting of the uprising was virtually the last act on Do The Right Thing. Sal’s Famous Pizzeria had been specially constructed on the block, with the clock slowly ticking round to its destruction.

Turturro: The only thing that was really uncomfortable with the end of the movie was the end. There were a lot of people who were inexperienced. It was stomach-turning to do it after we had all worked together well.

Reed: I have yet to experience anything like it. There was such anticipation leading up to it, because we knew what the end of the script was. That beautiful building that had been built for this movie was going to be destroyed.

Esposito: We’d had to act as if we hated each other. By the end of the film there had to be a release of some energy. That energy, thankfully, could be filmed.

Turturro: Sometimes things got a little hot with certain people. Some of the people were jumping on top of me and pounding me. They were young actors. I said, “Hey guys, you can’t really hit me. You have to pull. Otherwise you’re gonna really kill me.”

Lee: Danny Aiello III [his son] was Danny’s stunt person. There was a scene where everyone comes flying out of the pizzeria onto the sidewalk. For some reason Roger Smith was spitting. It could have gotten ugly, to say the least. It was heated, though.

Roger Smith: After Spike said, “Cut!”, Danny’s son jumped up and said, “Who the fuck is spitting on me?” I had to explain that Smiley is disabled. It was a character choice.

Dickerson: In the burning pizza parlour, showing the flames engulfing the pictures on the wall, I remember there was glass in the frames exploding, and being hit with hot glass. It got a little warm in there, but it was all safe.

Reed: You had to get it in the first take, because there wasn’t going to be a second one.

Lee: There was supposed to be more than one take in the burning of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, but the extras destroyed it the first take and that was it. There was no way to go back and rebuild that. They tore that motherfucker apart.

Smith: It was extraordinarily cathartic.

Lee: So, I’m getting ready to do Jungle Fever, and I want to use three Frank Sinatra songs. I got told, “You have to speak to Tina Sinatra.” She said, “Spike, I really like your films, but my father’s mad at you.” “What did I do?” “He doesn’t like the fact you burned his picture in Do The Right Thing!” I said, “I’m sorry! I love Frank Sinatra!” She said, “You need to write my father an apology.” I wrote a lengthy apology. I got those songs.

Do The Right Thing debuted at the Cannes Film Festival in May of 1989, and when it opened in the US on 21 July, around the same time as Tim Burton’s Batman, it created something of a kerfuffle amongst a certain type of film critic (back then, pretty much the only type of film critic).

Lee: When Do The Right Thing premiered in Cannes, there was pressure put on Tom Pollock, who was then the president of Universal Pictures, not to release it. Especially in summer time, because this film would incite black people to riot and run amok.

Turturro: One of the people who said that became a political writer. I was a little bit worried about it because I’m the racist character. Some people who had never worked on a movie before would look at me on set like I was that person. I said, “Spike, you gotta put me on the cover of Ebony magazine with your arm around me when it comes out!” He would laugh. But I have not had one incident in all these years.

Dickerson: A lot of critics were just trying to find something incendiary to write about. It was pure ignorance on their part. Nothing ever came of it, of not really knowing what African-American film is, and what it’s capable of. It’s not something that will cause the destruction of American society, but actually contribute to a better America. Best thing you could ask for, to have that last laugh.

Carter: We were like radicals in that we were brave enough to present this point of view. Critics who were used to Hollywood — watered-down, Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air, non-threatening views — were trying to protect everyone from something that was way too reality-based, and way too heavy.

Lee: Research the articles by David Denby, Joe Klein, and Jack Kroll. Basically, what they said was, blood was going to be on my hands because black people were going to riot and it was going to be my fault. It was very racist reviews. If you write that, you’re saying that black people don’t have the intelligence enough to distinguish between what they see on screen and what’s real life. Not one of them has apologised or said what they wrote was wrong, with a capital W. I’m upset 30 years later.

Esposito: I saw a cut not very long ago. I felt like the tension in the film was palpable. You feel people’s anxiety. You feel their helplessness in many ways. You feel the heat take a toll on their actions and emotions and you feel like they’re screaming for justice. And I think this is still going on today in our society because the gap is still getting wider.

Turturro: I think progress has been made, but it’s incremental. It’s not like something changes in a big way, I think.

Lee: For their first date, Barack and Michelle [Obama] went to see Do The Right Thing. The joke I add to that is, “Good thing he didn’t take her to see Driving Miss Daisy, or that would have been the last date!” She would have said, “What is wrong with this brother?”

Do The Right Thing is out now on Criterion Collection Blu-ray.