As part of our Empire 30 celebrations, director James Cameron writes about his love of cinema, what inspired him to become a filmmaker, and what keeps him pioneering into the future of the medium. Originally published in the January 2019 issue of Empire.

Before I ever dreamed of being a filmmaker, I was in love with cinema. As a kid, I knew all of the old B sci-fi films from the 1950s by heart. I’d record them on a little audiocassette recorder I got for Christmas, then listen back to them later and replay them in my mind, because home video was still decades away. Inspired by those movies, I’d draw pictures or build my own robots. Not that they were very sophisticated robotics — they were cardboard boxes filled with paper-towel tubes, and if you turned a crank they would dispense Maltesers. I made them as Mother’s Day presents and things like that. I also built humanoid robotic torsos and put them on top of a remote-control toy tank, which I’d drive around. I guess that was the precursor to the treaded Hunter Killers in The Terminator.

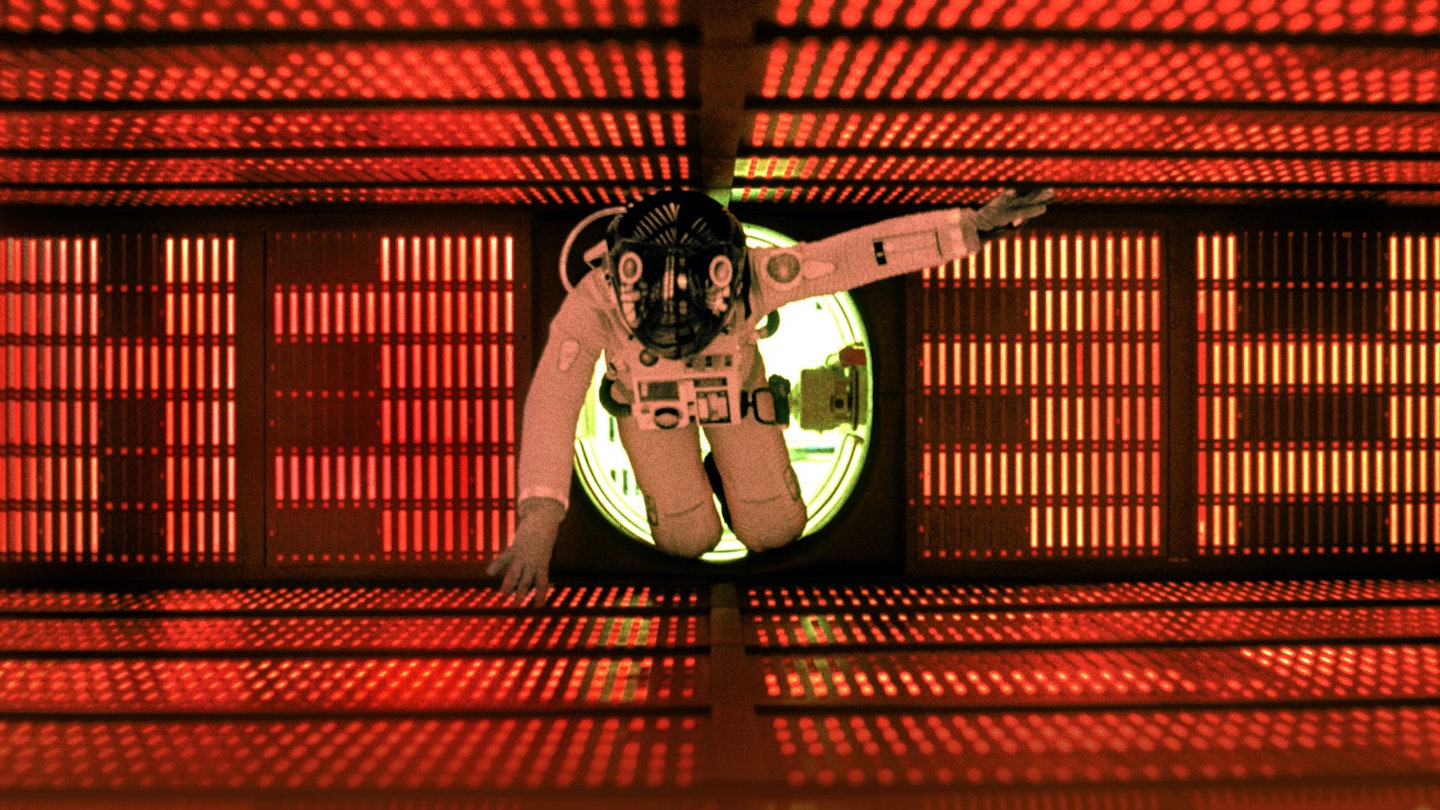

It was 2001: A Space Odyssey that toggled a switch in my brain and turned me into a practitioner. I was 14 and had never picked up a camera before. But now I wanted to know how visual-effects shots were made. So I got my dad’s Super 8 camera and started building model kits of the spacecraft in the movie. I read the 2001 ‘making of’ book probably ten times. And I figured out that if you painted tinfoil black, put a light bulb behind it and poked pinholes in it, you could make a pretty decent star field. My first epic space story had a budget of probably ten bucks. But it got me off my duff.

Back then, however, I didn’t know if I wanted to be a writer or an artist or a physicist or an astronomer or a sculptor. I was all over the map — my brain was just firing in all directions at once. And I didn’t really focus on the idea of being a filmmaker for real until I was in my mid-twenties. In my mind I had all these images for hyper-kinetic space battles, with aerobatic motion and energy weapons firing and ships exploding. Then I went to a movie theatre and saw a little thing called Star Wars. And I felt like one of those paranoid-schizophrenic people that puts a little bit of foil underneath a wig to keep the CIA from spying on their thoughts. Because the images I had in my brain were up there on the screen. For me, it wasn’t the shock of the new — it was the shock of the familiar. And I thought, “If the world rewards this film as resoundingly as it has, then there’s a market for what’s in my brain.” It was time to get busy.

A year on, in 1978, I was on a set with two friends making Xenogenesis, a proof-of-concept reel for a complete science-fiction feature. We managed to talk this girl who wanted to be an actress and another friend of mine who was a writer into starring in it, as a young space couple. It was wildly ambitious, completely impractical and pretty dreadful, but the imagery is actually not that bad. And I learned an awful lot. How to run a 35-mm camera, how to do in-camera matte paintings, how to rotoscope. And I got to say “action” and “cut”. That’s when you become a director. All you have to do is shoot something and say “action” and “cut” a few times. Everything after that is just negotiating your price.

Forty years on, the bug is still there. The only thing that’s going to stop me from making films is getting hit by a cement truck or the inevitable march of time. But I think now I have Hollywood more in perspective. There was a time when making a film was the most important thing in the world to me. Now, it’s not. It’s a thing that I love to do. But I know how important my family is. And some of my activities around food and sustainable agriculture and exploring are equally important. So I have it in perspective, and that’s a very, very healthy place to be. Otherwise you can be bruised and damaged psychologically by Hollywood in general.

We can do anything right now. With digital tools and enough money, there are no limitations. And that makes it even more important that we’re disciplined.

That said, I have enough of a work ethic that it’s not like I’m ever phoning it in or slacking off. My schedule is as intense now as it ever was. And I like that just fine. I don’t know what to do with myself if I have a day off, so I just work continuously. I think my wife would prefer that I took a little time off from time to time. But I get nervous and pace around and think about all the things I could be doing, so it doesn’t really work for me.

I still get a buzz from filmmaking on a fairly regular basis. I get it every time we lock a scene for the new Avatar films, because the process is piecemeal. You don’t have dailies and all that sort of thing — it’s all done with capture. So all you see is people in spandex tights for a long period of time. And then there’s a moment where you walk into what we call a ‘camera session’ and actually see the colours and characters and so on. It’s all whacked together and suddenly you’re watching a scene that’s taking place in a bioluminescent ocean, or flying in the air with some fantastic creatures. That’s when I think, “I have the coolest job in the world.”

All filmmakers create a sort of reality bubble around their characters, whether it’s an apartment building in Florida or a far-flung planet. It’s really just thrilling to create something from nothing. And although every single atom of the fabric of filmmaking has changed — as of the first Avatar, we’ve even done away with the physical camera — the basic principles are the same. All the different styles and ideas that were pioneered throughout the age of the physical photochemistry of film are still extant now. It’s just that we’ve gone far beyond that in our ability to create another reality.

We can do anything right now. With digital tools and enough money, there are no limitations. And that makes it even more important that we’re disciplined. Now, once I capture a scene with actors, I can put it on the moon, or underwater; I can play it all in one master shot or do it in 30 close-ups. Having infinite choices, it forces you to really understand the creative decisions you’re making at every second.

I feel very positive about what’s possible. If you look at all the big movies of the last decade, there’s very little in the way of original IP that gets to inhabit the billion-dollar club, or even the half-billion-dollar club. But I still believe it can be done. Titanic didn’t fit any mould of its time. It’s a big no-brainer now when you look back at it, but at the time it didn’t make any sense as a film done on that scale. Everybody knew that the ship sank and the people died. It wasn’t going to be part of a franchise. It certainly didn’t have a feel-good ending. As for Avatar, that was practically pronounced dead by the powers that be before it was released — I remember the head of the studio at the time saying, “Avatar’s just a word. It doesn’t mean anything to people.” I guess what I’m saying is that you don’t have to play by the rules if you don’t want to.

In terms of the world at large, it feels like we could be heading for another Dark Age. That’s what I look around and see. The film industry tends to be very liberal, and we pride ourselves on being the pioneers that are going to show everybody a better way when it comes to civil rights and gender issues and so on. I look at the political landscape right now and think, “Well, guess what, guys? That didn’t work. We’re just as benighted and fucked up as we ever were, if not worse.” It used to feel like we were always moving forward, even if only in small steps. I never thought we’d suddenly wind up losing so much ground.

But I still like to think that film and television is a shining light, where we get to have a sense of communion as people. We get to celebrate human nature. We get to walk in the shoes of other people. We get to have an empathic reaction to the plight of others. Even if that doesn’t seem to be enough anymore, it doesn’t mean I’m going to back off the throttle. Not one iota.