As part of our Empire 30 celebrations, Chris Hewitt interviewed Danny Boyle about his genre-hopping filmography. Originally published in the May 2019 issue of Empire.

The first time Danny Boyle thought about what it might mean to be a filmmaker was in a Bolton porno cinema in the early ’70s. Aged 16, he could pass for 18. Which meant he was the one to get the tickets, then dash round the corner to find his mate, who didn’t look anywhere near old enough to see A Clockwork Orange.

“The width,” he extols of those Kubrickian images. “I understood that a filmmaker wanted us to feel how a film was made. What’s it called? That vanishing point, one-point perspective, where the film disappears into infinity.” He would borrow the technique for Shallow Grave, 28 Days Later and Sunshine.

Since that heady day, with undimmed enthusiasm, he has tackled many genres. There is no area of cinema Boyle won’t dive into — he even once tried to get a new version of My Fair Lady off the ground, with Daniel Day-Lewis as Professor Higgins. But one thing is consistent throughout his filmography: nothing is ever quite what it appears to be. This is the man who directed an episode of Inspector Morse — about rave culture. All of his films fall under the magical aegis of Boyle’s Law: unpredictable, groovy, visually daring and often profound, an inspiring fusion of British instinct and American inspiration.

“The reason that you are storytelling is to take people to places they have never been before, or to experiences that they cherish, or fear,” he says. “You are not running a political party or a church. You are an entertainer. But cinema has power — you are transformed by it.”

The Thrillers

At the end of his first day on Shallow Grave (1994), Boyle walked into producer Andrew Macdonald’s office with a grin. “Well, we’ve started, so we’re going to have to finish,” he told him. He was directing his first feature, letting his ideas loose on a dastardly tale of three flatmates in Edinburgh, confronted with a dead body and a suitcase of ill-gotten cash. Naturally, they elect to do the wrong thing. The result was like a jolt of electricity. A smash hit, rattling multiplexes up and down the land.

Boyle is happy to acknowledge that he was “inspired by great American filmmaking”. He was openly riffing on the Coens, Scorsese, Coppola, maybe a bit of Kubrick too, as his camera glided along corridors, dread hanging in the Scottish air.

“When you went to the cinema, that was the stuff that excited you,” he reasons. “Why make a film that didn’t excite you? What was the point in that? We wanted to make a film that was as exciting, if not more exciting than their films. That was my template. Especially, in the visceral, violent world of the thriller.”

So he never worried that his three lead characters — played by Kerry Fox, Christopher Eccleston and Ewan McGregor, Boyle’s erstwhile muse — were not exactly what you would consider likeable.

Boyle laughs. “It’s like Capra said: ‘There aren’t rules, there are just sins. And the only cardinal sin is dullness.’ Which is absolutely true. In the thriller format your characters escape from being judged. That is one of the joys of it. They are good films to start off with, thrillers, because people are expendable.”

Trance (2013) featured another unlovely threesome, played by Rosario Dawson, James McAvoy and Vincent Cassel, caught up in a Russian doll of plots within plots, stolen art, missing bodies, blackmail and betrayal. Another team-up with writer John Hodge, it turns on the idea of hypnotism unlocking not only unforeseen secrets, but an entirely different film. It is Boyle’s knottiest creation: a heist thriller that spills into a psychodrama about abusive relationships.

Boyle even had his cast hypnotised for the full immersion. “Coming out of theatre, I work hard to make sure actors are believable,” he says. “So I like surprising, shocking and disturbing them.”

The Adaptations

Boyle remembers getting the Central Line from Tottenham Court Road with 18 typescript pages of Trainspotting (1996) in his hands. When the Shallow Grave team contemplated the madness of adapting Irvine Welsh’s stupendously unfilmable novel — a fractured series of vignettes cataloguing the unsavoury antics of a huddle of Edinburgh heroin addicts — Hodge offered to try “writing a few pages”.

“I remember reading those pages and just laughing,” says Boyle. “Because I had read the book, and it wasn’t the book, but it was the book. I remember thinking, ‘This is brilliant.’”

Despite the extreme places the story goes, it felt instantly relatable. “For the actors as well, who are giving very extreme performances… It connected with everything we knew about ourselves and the world around us. Even though it was through the prism of a very particular group of people. Which, I think, is the reason it was a hit.”

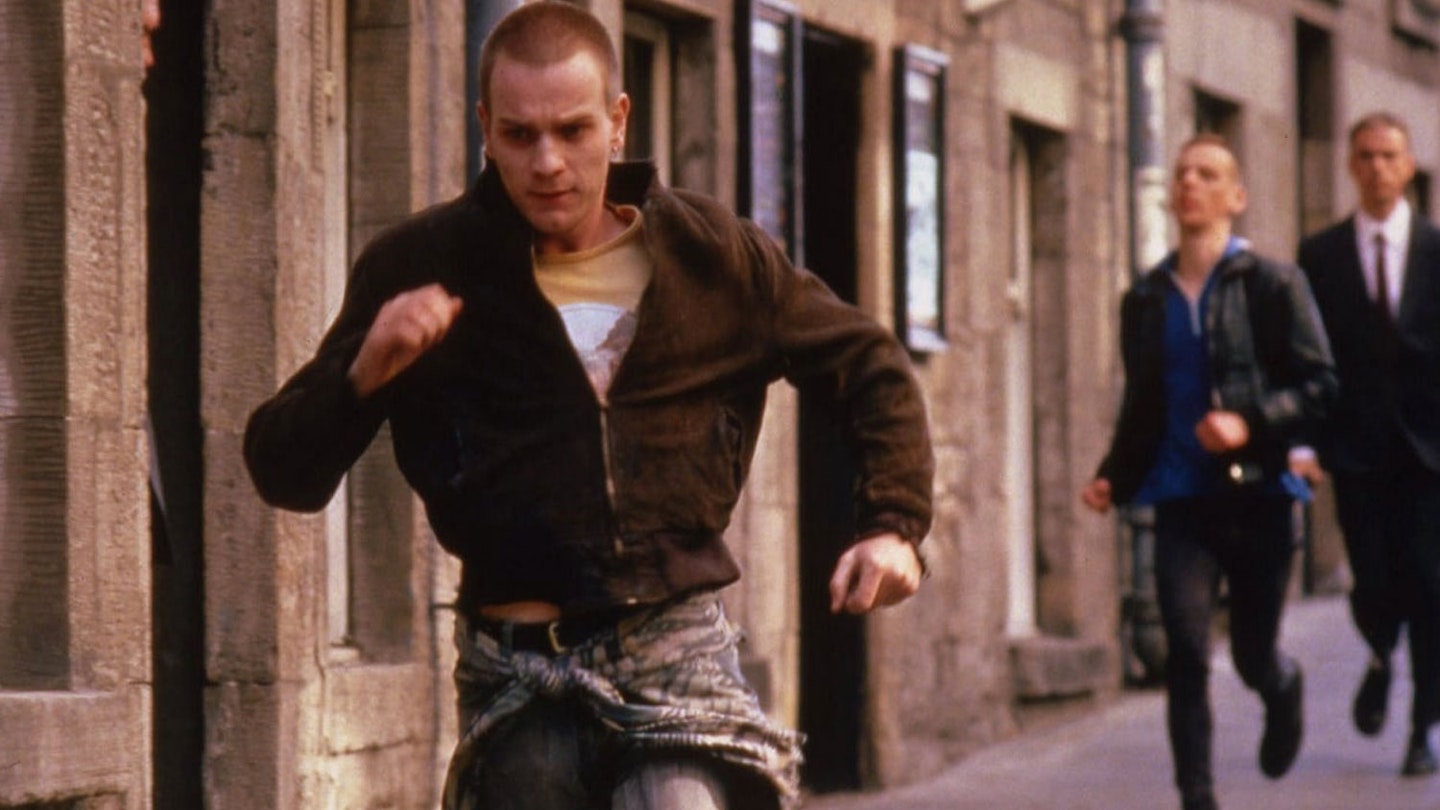

During filming, he allowed room for collaboration, and for chance to play its hand. Take the film’s opening, the most famous scene of Boyle’s career: McGregor’s Renton, rake-thin, shaven-headed, bolting down Princes Street to the pile-driver high of Iggy Pop, bestowing his sardonic-Yoda homilies via voiceover. Choose life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Boyle had planned for that to be the heart of the film.

He sat cinematographer Brian Tufano down and told him they needed a Steadicam. “Which I really didn’t know anything about,” he admits. Tufano knew better. They needed a quad bike.

“We didn’t get permission to have a quad bike,” laughs Boyle, back again in his unstoppable youth, fuelled by sheer cheek. “We pretended it was just going to be a service vehicle, but actually it was ploughing up and down the pavement of Princess Street.”

Then weeks later, in the dark of the edit, Masahiro Hirakubo, the editor, asked to try “putting that voiceover at the beginning”.

“And there you go,” grins Boyle. The entire film came alive in an instant.

When it came out, Trainspotting flared as bright as sunshine. Boyle was anointed the figurehead of a generation. “You get a glimpse of what it must be like to be one of those pop stars who hook into the moment,” he recalls. “They are the taste for however long it lasts.”

Looking back, it’s not the cultural spasm, or all the posters the colour of orange peel, that springs to his mind. Rather a single scene: his four leads — McGregor, Ewan Bremner, Robert Carlyle and Jonny Lee Miller — sitting in the pub with a bag of life-changing money.

“They were just there, mates distrusting each other. It was perfect. And then Bobby glassing that guy. You just think, ‘This is proper acting.’ It was a nothing scene but it is absolutely mesmeric. And it sums up that film: ‘What’s it about? What is it actually about?’ But you can’t stop watching them.”

They would all return for the sequel, 20 years later, middle-aged men. Boyle struggled with the idea of going back for T2 Trainspotting (2017). “You don’t have a healthy relationship,” he says, “because it is constantly being commented upon by everybody.” He had a set of jokes ready for what had become of those guys. Only the joke got real and the film started to “manifest itself” around a simple catalyst: “Let Renton have a heart attack and see what happens.”

It is a frighteningly honest sequel, a ghost story haunted by the fervour of the original and its thrilling moment. Between the jokes was an abiding sense of loss. “McGregor walking back into his bedroom, and seeing him dance…” sighs Boyle. “They are declining. So there would be a regret.”

Like Trainspotting, Alex Garland’s The Beach was a paperback du jour. Another clique of outsiders turning on one another. In this case, backpackers communing on an idyllic Thai beach. The sort Renton would consider wankers. Which was partly the point.

The Beach (2000) was Boyle’s first true studio picture. And with it came Leonardo DiCaprio, a bigger budget and all these expectations. “It was all about the cost of making the film,” he groans. “That we’d need a bigger star than Ewan... Ewan was about to do Star Wars!”

It was a difficult production; the studio kept talking him out of things. As his finale, Boyle had planned a massive, symbolic storm, nature’s reckoning. “We got talked out of that because of expense,” he laughs. “Yet when you look back, you think, ‘Hang on a minute — the reason we cast Leo is so we could make the film exactly as we wanted to make it.’ You learn. If I could go back, I would approach it in a different way, I suspect. ”

The Rom-Coms

When it came to madcap, on-the-lam romantic comedy A Life Less Ordinary (1997), which had the unenviable task of following the life-changing one-two of Shallow Grave and Trainspotting, Boyle admits he was trying to break America.

“How ludicrous is that?” he declares. “But there is proper damage done. John Hodge’s script, originally, was less trying to be a romance. It was very brutal. This road trip between France and Scotland. There were no Americans in it. We changed all of that.”

They relocated to America to shoot in LA and around Salt Lake City. They cast Cameron Diaz as the rich bitch who falls for her fumbling kidnapper (McGregor). They added the angels (Holly Hunter and Delroy Lindo): a touch of the metaphysical that harkened to Boyle’s love of Capra. The result was an off-kilter mix of wit and whimsy, a bit Coen, but off the Boyle.

“We wanted to do something so different from Trainspotting,” he admits. “That is a good thing, but it is not necessarily what you should be doing. I had grown up on American films. When they get it right, there is nothing like it. It mobilises the whole world to look at a cinema screen. And you are tempted by that.”

After he finished shooting, he happened to read the script for the more conventional Notting Hill. “I thought, ‘This is why A Life Less Ordinary won’t work,’” he recalls. “We are just going to piss people off. Which we duly did.”

The Horror

28 Days Later (2002) is archetypal Boyle, a gritty synthesis of ’70s British science-fiction tropes (principally, John Wyndham’s The Day Of The Triffids) with George A. Romero’s zombie movies. Another example of him plugging a British film into an American socket.

The London sequences that open the film needed to be shot months before the body of the script, which pitched survivors against maniacs infected with the Rage virus, like a battalion of Begbies. “We shot it in July, because we wanted to shoot at 4am, before London woke up,” says Boyle. Over six days, for a couple of hours a day, holding back the occasional grumbling early commuter, he assembled those haunting, dreamlike scenes of Cillian Murphy wandering alone past London landmarks.

With 28 Days Later, it turned out, Boyle was bordering on the prophetic. Britain, today, is a country afflicted with rage. “I know,” he winces. “There is at the moment such intolerance of each other. We made it because of road rage, which was a microscopic example of what has become, through social media, a kind of a fashion of intolerance.”

The Fables

Boyle might be an atheist, but God keeps butting into his films. His Catholic upbringing has something to do with it, he likes the idea of something mystical out there in the universe. Sunshine (2007) was ultimately a trip to meet our maker, while Millions (2004) had a small Liverpudlian boy converse with the saints.

Making a straight-up kids’ movie, written by playwright Frank Cottrell Boyce, is possibly the most shocking thing Boyle has ever done. We should have noticed that he was essentially remaking Shallow Grave with a seven year-old: the bag of stolen cash, the ethical dilemma, a fellow in the attic. Only Damian (Alex Etel) tries, delightfully, to do the right thing.

“Right from Shallow Grave, we were seeing values shift away from the social classes,” says Boyle on why his films are so often set in motion by a pile of cash. “It was becoming about money. That is what gave you a position in life.”

Who wants to be a millionaire? That is surely the key question in all of Boyle’s work.

For Boyle, Mumbai was like a drug. And Slumdog Millionaire (2008) became the scene of his Oscar triumph. He fed off the city, lived it, absorbed it, and poured it into his thrilling, realist fable of a boy (Dev Patel) rising from the slums to win the girl (Frieda Pinto) via that famous TV gameshow. It was Boyle doing Dickens by way of the Maximum City. “Mumbai is this inside-out world,” he extols. “The insides are all visible, literally. It is very intoxicating. You went out there and let it breathe into the film.”

Boyle has few memories left of Oscar night. He can recall the build-up, as the film passed between festivals and talk grew that here was another sensation, like Trainspotting, but more crowdpleasing, more universal. But his great night?

“Reese Witherspoon, who presented Best Director, grabbed my hand,” he remembers. “As you step off stage they watch for you fainting. Because the adrenaline is so high, but as you step off the stage it collapses. People faint. I never knew that — stars buckling.”

The Sci-Fi

Science-fiction didn’t suit Boyle, though there is a lot to be said for Sunshine, his dalliance in Kubrickian bigness. Ironically, it was the detail that nearly killed him. He felt trapped in the claustrophobic sets, reminiscent of Alien, equally stocked with decent, expendable actors like Murphy, Chris Evans and Rose Byrne. He was maddened by the glacial pace it took to create CGI for this journey to kickstart a failing sun. He let the big ideas get the better of him. At the end, he had Murphy’s physicist touching the face of God, or the sun.

“Alex and I fell out about that, because Alex is a proper committed atheist,” he smiles. “His ending of the film was they play chess as they hurtle into the face of the sun. Whereas mine was he literally reaches out and touches something — that you can call whatever you want to call it.”

The Biopics

If you want an American equivalent to Boyle, then it is David Fincher. There are huge differences, of course, but their careers have meshed in strange ways. Fincher fell into the abyss of Alien 3, while Boyle swerved Alien: Resurrection. Boyle turned down Fight Club before Fincher grabbed hold. And Steve Jobs (2015), Boyle’s biopic of Apple’s titular savant, fell his way because Fincher departed.

“You read a script like that and think, ‘If I’m not going to do stuff like this, what is the point being around?’ Then you find an actor with the courage to do it, like Michael Fassbender.’

Fassbender was channelling unknowable forces, delivering long, long takes of Aaron Sorkin’s Shakespearean jive. “He didn’t look like the guy, but there was something about him that got close to the furnace that this guy was — this furnace of pure ideas.”

Interestingly, both of his biopics are about Americans. Which might be a red herring. They are really about obsessives. You might say, addicts.

“I’ve always worried about doing stories that are too embedded in American culture,” says Boyle. “So the two I’ve done, in 127 Hours he is trapped in a kind of a mythic place, and [Steve] Jobs is trapped inside the launch of three products. They are very interior worlds, rather than big social worlds.”

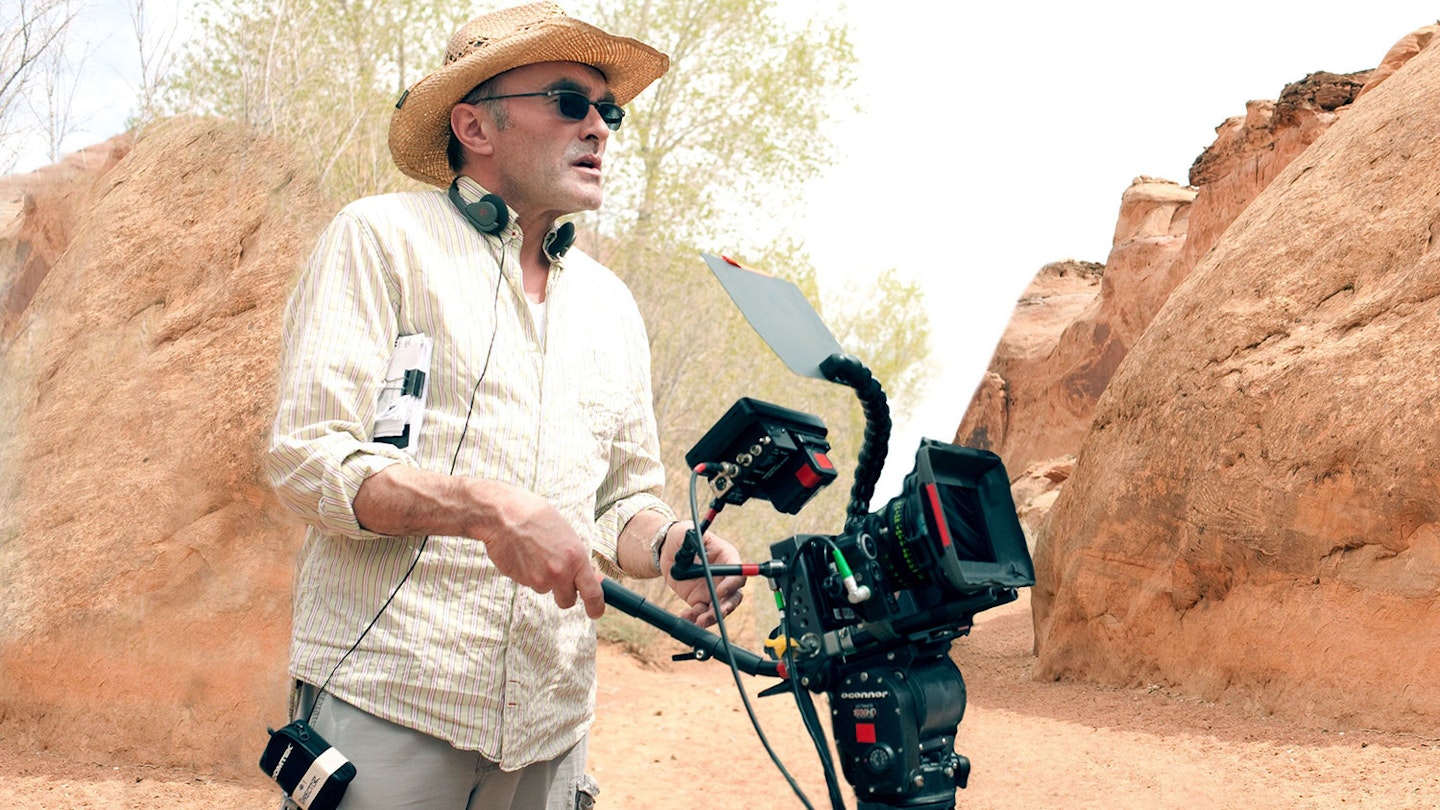

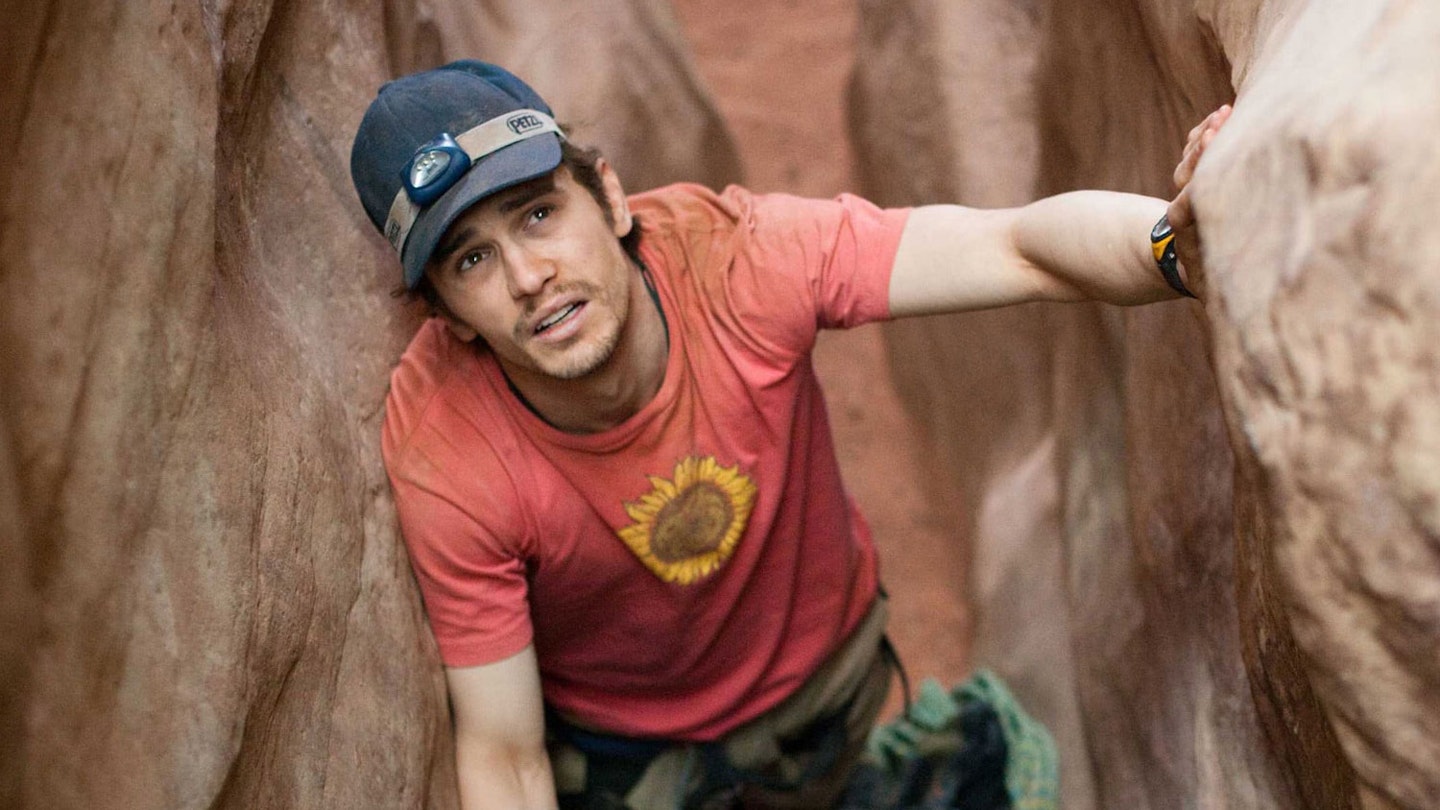

127 Hours (2010) sees Aron Ralston (James Franco), adrenaline junkie, his arm pinned by a boulder in the Utah wilds, face the ultimate test — are you ready to cut up your own body?

On location, Boyle had to draw heavily on his own reserves of ingenuity. “I’ve always loved a box,” he says. “I don’t want limitless resources. I much prefer to have a small bunch of people and work out how we can do it.”

It may be the purest Danny Boyle film there is, the kind of visceral experience that you can only get from cinema. “It was about trapping you in there with him,” he concludes. “So that when the moment of release came, you would feel it too.”