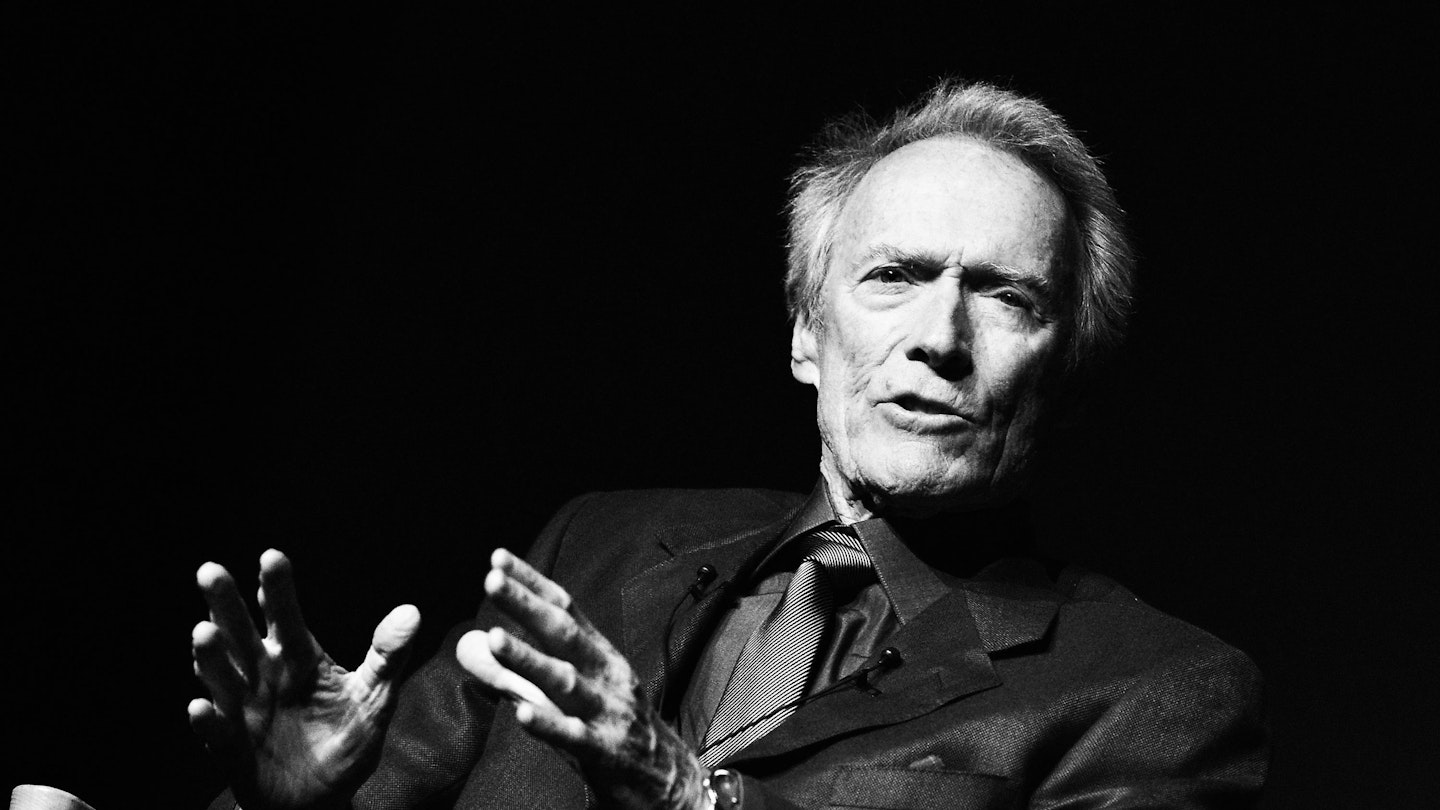

In a rare interview, the great actor-director talks Empire through the films that have defined his career: Westerns, thrillers, politics, humour, romance, mortality, a cop called Harry and an ape called Clyde.

The Good, The Bad And The Ugly

(1966, Sergio Leone)

"Sergio was terrific for me," declares Eastwood. "I was this young man, having done three years on Rawhide, with an Italian director who spoke no English. I thought it was insanity and that insanity was intriguing for me." Thus began the relationship that would shape his entire life, ultimately transforming him into an iconic actor, an uncompromising director, and a master purveyor of the art of the Western. "I thought there will be a whole different approach, but it'll probably just be awful."

I was the young guy who didn't have to worry too much.

In some ways it was awful, even by the last of his Spaghettis, he shared a room with Eli Wallach, alternating use of the single bed. Communication with Leone was minimal and that is exactly what worked. Eastwood's approach to this taciturn killer, all growls, squints and swift draws on a cheroot that made him nauseous, now a tidy witticism: "Don't just do something, stand there!"

"I was a big fan of John Ford, and Sergio was too, but his approach was so different: he had no restrictions, he'd kind of go off and do what he wanted even if it was somewhat satirical. It was certainly different from me."

The Good, The Bad And The Ugly is undoutedly the highpoint of their mysterious bonding: contained within its wild, swaggering style, is a sad cry against the cost of war, with Spain's Almeria standing in for a desert state in Civil War USA. He's never been one for the long haul of production – "it was long, ten weeks on that one" – but still, the result is a gleaming pleasure that enthrals generation after generation. "I think everybody likes to delve into them," says Eastwood, who wriggled free of the terse killer when Leone came calling for Once Upon A Time In The West. "I remember when I was doing White Hunter Black Heart in Africa," he laughs. "We had all these British actors, and almost every actor said, "Hell, I would like to do a Western with you. I grew up on those Spaghetti Westerns.'"

Where Eagles Dare

1968, Brian G. Hutton

"My agent felt it would be a great idea to pair up with an actor senior to me," starts Eastwood as mystified by the ways of agents as anyone. "In this case it was Richard Burton." Based on an Alistair MacLean novel, this brusque, often incomprehensible, but entirely entertaining bit of WWII derring-do seems predicated on the idea good-looking stars look even better in Nazi uniforms. From Eastwood's point-of-view it was a good payday ($800,000) even if he got second billing, and an opportunity to prove himself a on different ground. "It wasn't a role that was very challenging for me," he admits, "but I got to go to Austria and work with a lot of new people. I thrive on those experiences."

Its barrage of nifty stunts and snowy locations, and the ping pong of double crosses that make up the twist ending, have granted the film a bank holiday charm. Although it was a long, arduous shoot - all the fuss Eastwood hates - he and Burton got on swimmingly. "Richard was quite a character," he laughs fondly, "and of course he was with Miss Taylor at the time, they were sort of the couple. I was the young guy who didn't have to worry too much."

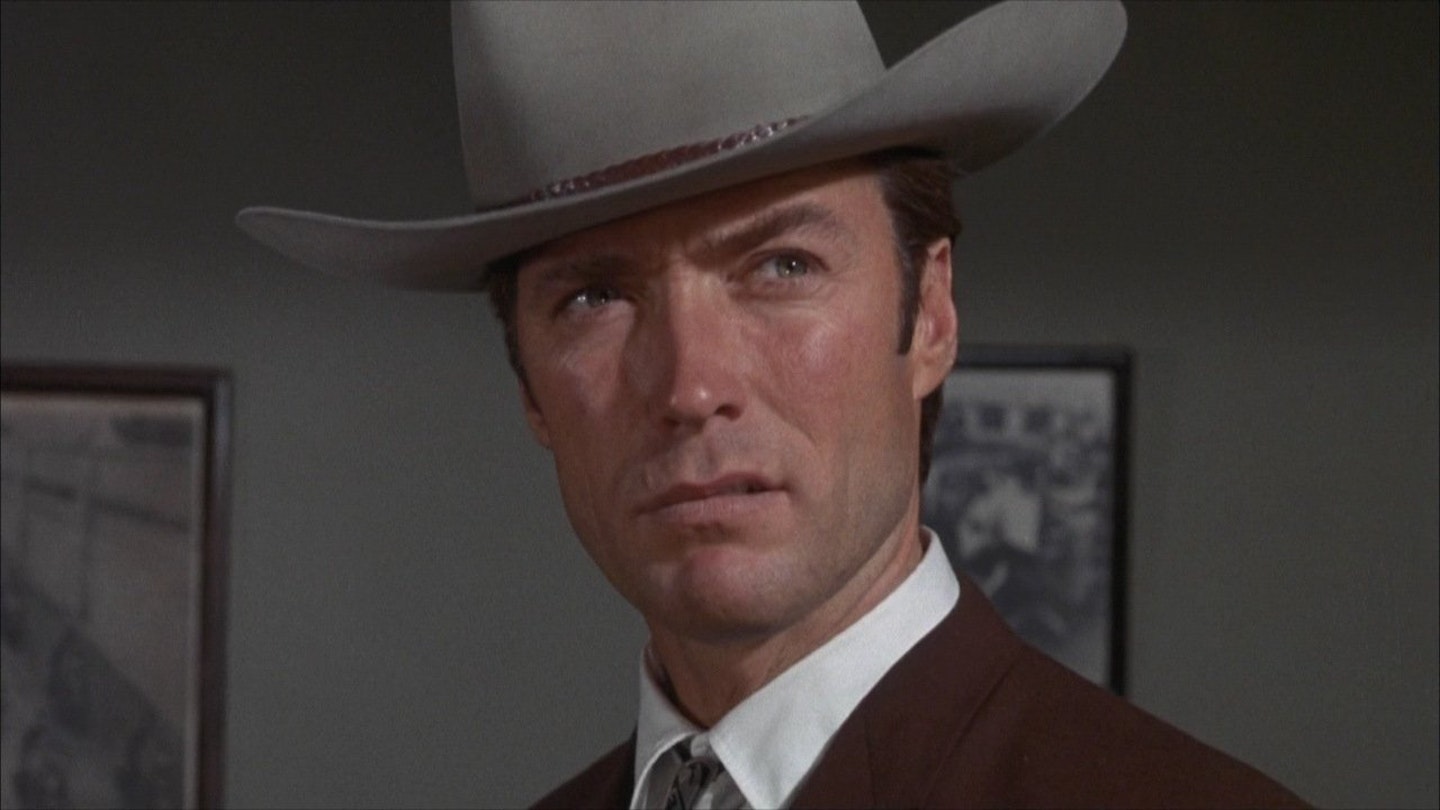

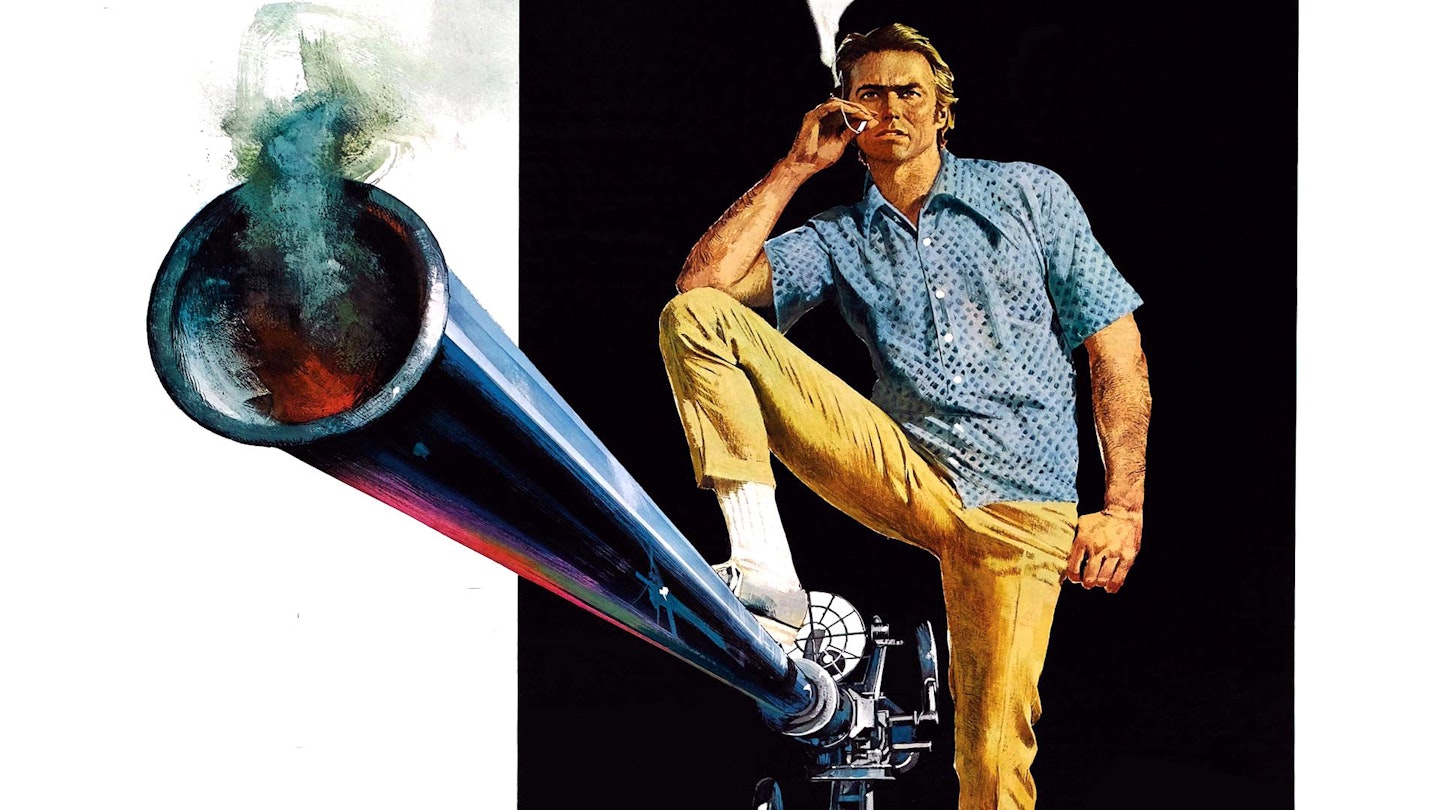

Coogan's Bluff

1968, Don Siegel

"I talked with several actors. Lee Marvin was one, and they all said they liked him, so I agreed to meet him." So began one of the pivotal relationships of Eastwood's career: his friendship and fertile creative partnership with director Don Siegel. "I ended up liking him very much, but we had to piece that script together."

Coogan's Bluff is a key movie in the evolution of Eastwood's star image, catching him halfway between Western bounty hunter and off-the-leash policeman, this also offers a parallel with Midnight Cowboy as the straight-looking, stetson-hatted hero is treated as a joke by kooks, deadbeats and freaks who sneer at his John Wayne values, prehistoric sexual attitudes and faintly camp boots.

It's an unusual film in that it's out of love with its hero, who comes over as a callous, self-centered, unnecessarily brutal bastard, though, by the fade-out, Coogan has softened his dead right values enough to show some sympathy for his battered captive. The cowboy cop-out-of-water theme was reprised in the Dennis Weaver TV series McCloud, but Eastwood and Siegel were headed for Dirty Harry. "We argued once in a while, but most of the time we got on pretty well, " says Eastwood of the director. "We'd sit and bounce ideas off each other. He was a terrific guy and an efficient director and I learned a lot of my efficiency from him. He didn't monkey around much."

Paint Your Wagon

1969, Joshua Logan

"I was crazy enough to try anything," says Eastwood of his one and only venture into the world of the musical (as of yet). "I've always been interested in music, my father was a singer and I had some knowledge of it. Although what I was doing in that picture was not singing."

What I was doing in that picture was not singing.

It was more talking in a singsongy way as the tunes by Alan Jay Lerner glided through the air. Mind you, co-star Lee Marvin reduced the idea of singing to a basso rumble more akin to Whale song that the Broadway from whence the whole gold prospecting-love triangle nonsense came. Even though the filter of a western, and without the assistance of an orang-utan, it could be the craziest thing he has ever done. As the script went through innumerable rewrites away from the darker story - it originally featured an inter-ethnic romance - that had initially attracted him, Eastwood nearly bailed. "I was away shooting Where Eagles Dare, and they flew over (Alan Jay Lerner and director Joshua Logan) and talked me back," he sighs, nearly 40 years later the film is still not to his liking. "It was much lighter, it just didn't have the dynamics that the original script did. And that was another long shoot..."

Beset with production problems, the film took six months to finish and went wildly over budget. Kryptonite to Eastwood: "That was not as pleasant an experience as I was used to," he growls.

Kelly's Heroes

1970, Brian G. Hutton

"That script had a lot of the depth to it, sadly a lot of that was taken out in favour of entertainment." Eastwood's second movie with Brian G. Hutton, after Where Eagles Dare, may also be set in WWII but is a different beast entirely. It's a goofy caper movie in which a squad of American troops, with the oddball energy of the Animal House frat (significantly John Landis was an assistant on set), track down a stash Nazi gold on behalf of themselves. It's the Three Kings of its day, with Eastwood reduced to playing straight man as the likes of Donald Sutherland and Telly Savalas cut loose. Satirical and amoral, it had the spirit of the '70s (MASH was released in the same year) and feels as much a reflection of Vietnam than the war in Europe.

And it was a blast to make. "We were all in Yugoslavia, this bunch of crazy souls: American, British, French, German, Italian and Yugoslav. All those languages being spoken during the production. It was like being back with Sergio."

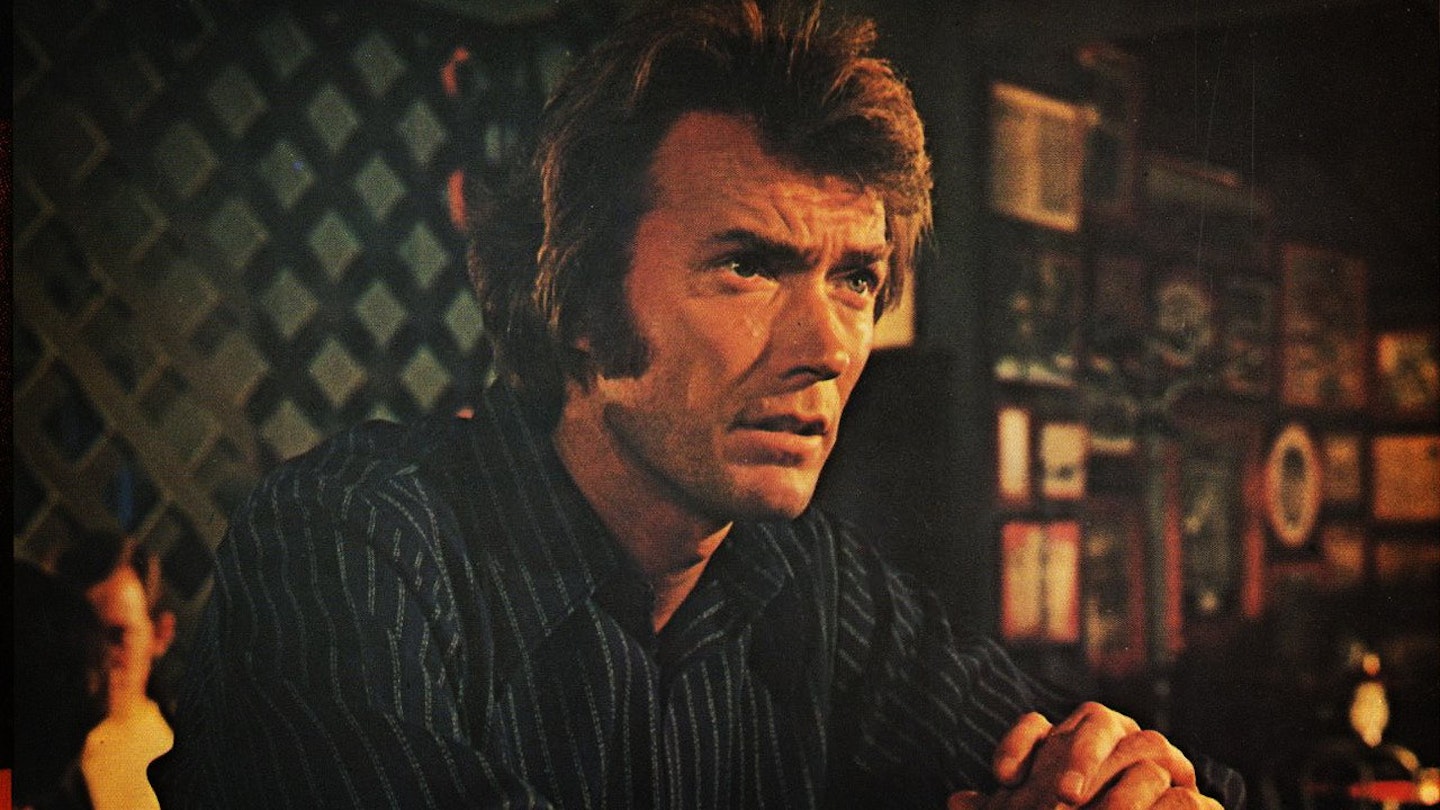

Play Misty For Me

1971, Clint Eastwood

”At sometime in everyone's life, regardless of the situation they are in, they have had some kind of uncomfortable relationship like that. Where one person interprets a relationship one way and the other person doesn't see it that way." A pitch-black psychodrama about a small-town DJ (played by Eastwood) stalked by an obsessive female fan, was an unexpected place to set sail as a director, but Eastwood had known the writer, Jo Heims, when she was a secretary and he an untried actor. When she handed him a 60-page treatment, he was drawn straight in. It just stayed in his head, this dark exploration of sexual obsession and celebrity - perhaps he could relate, fame was soon upon him: "I never had it that bad," he smirks.

Play Misty For Me would stamp the template for Eastwood's modus operandi as director: a personal project, a tight budget, creative focus (he took the setting from LA to Carmel: "It made more sense for the disc jockey to be a bigger fish in a small pond"), and his own rules. "I knew it was small, so I went to Lew Wasserman at Universal and said this is the project I want to make. He looked at me and said, 'Okay.'"

There was a catch. Eastwood was on a good deal at the time, so much a picture, and as it was his baby he could only take a percentage, a back end deal. "My agent was pretty disappointed, but I understood. I could screw the whole thing up, he was letting me prove myself." Eastwood has always been a brilliant player of the Hollywood system, wise enough to see limits as challenges: "I don't believe in pessimism," he shrugs.

The film has dated; it seems so mild compared to Fatal Attraction, which it inspired, but he draws a terrifically creepy performance out of Jessica Walters, making no bones about her character's madness. There is an insinuating, clammy quality to the movie like a knot that keeps tightening. "It was always at the back of my mind there was going to come a day when I would direct," says Eastwood. "But it came simply, I did one picture, then I needed to do a Western picture because that's the genre I was brought up in so I did (High Plains Drifter). Then one thing led to another and 28 years later I'm still doing it."

The Beguiled

1971, Don Siegel

“We did everything we could to make it as true to the book as possible and not sugar coat it," recalls Eastwood of this adaptation of Thomas Cullinan's eerie Civil War set novel. "The script had a little bit more of a up beat ending which was sort of ludicrous considering what comes before."

Eastwood was back with Don Siegel again – indeed he had requested him – but this was opposite the grizzled machismo they usually dealt in. It's closer in mood to Play Misty For Me, a seething interior drama where a wounded Yankee solider is first rescued by the women of a Confederate girls school, and then imprisoned. A situation sending both staff and girls into ever increasing fits of jealousy, ending in an astonishing sweep of grand guignol grizliness. One of his most underrated films, it required Eastwood to be virtually to sole male actor in a cast of full of women: "There's nothing wrong with that," he grins. "They were terrific gals."

Dirty Harry

1971, Don Siegel

"You kind of have a hunch," begins Eastwood on the question of Harry Callahan, tough-talking, rule-bucking, controversy-baiting San Francisco detective, the character who would define his career. "There was a loneliness about the guy, he had an empty life, but he also had this obsession with getting criminals off the street."

Harry was complicated – let's leave it at that.

Famously, the script had bounced in and out of Eastwood's hands, going by way of Paul Newman, Steven McQueen, John Wayne and Frank Sinatra, and directors too numerous to list. Originally written by Harry Julian Fink and called Dead Right, Harry could have been anyone, in any city. "But it was a good script, the writing was there," demands Eastwood. After the rounds and the re-writes, it gravitated back to his desk as if by destiny. "They gave me five different copies. It remained the first one I liked. Then they asked if I would like to do it with Don Siegel." Now it is impossible to see another other face than the glacial features of Eastwood as Dirty Harry. His city was another matter of destiny: "We were looking to make it in Seattle, but decided to stop off in San Francisco. It was this beautiful day. We couldn't go any further."

Harry is a hard guy to figure out. Is he right-wing antihero, breaking through the clutter of liberal values (Pauline Kael deemed him "fascist") or is he a troubled but noble soul, thrusting for a better world? It's the lack of definition that Eastwood loves: "People jumped to conclusions without giving the character much thought, trying to attach right-wing connotations that were never really intended. He was complicated, let's leave it at that."

Whatever its politics, the film, so fluidly made and powerfully written, is an undeniable classic. Sequels were inevitable. The first, Magnum Force, softened Harry's stance - he was gunning for a cadre of even dirtier cops. "I thought it was a good idea to maybe take a different tack," admits Eastwood. "Over the years the studio would call up and ask if I wanted to do another one. I would always say no, then all of a sudden someone would come up with an idea. I ended up doing a series of them."

Thunderbolt And Lightfoot

1974, Michael Cimino

"They said the writer wants to direct it himself." Michael Cimino wasn't unknown to Eastwood – he'd done a pass on Magnum Force the previous year. "So I said, 'Well let's take a shot with him, he writes rather vividly he should direct rather vividly." This is perhaps best-remembered as the film Cimino directed on time and under budget. As the title suggests, it's a light-hearted buddy/caper movie with an underlying melancholy suggested by the very '70s ending in which one of the buddies dies (these days, it would preview badly and be changed). Korean War veteran John 'Thunderbolt' Doherty (Eastwood), who sometimes poses as a preacher, spends his time with his wilder pal Lightfoot (Jeff Bridges) robbing banks. What starts out breezily in Butch and Sundance vein, darkens as it realises just how self-destructive the mock marriage of male-bonding can be.

"Everybody there was on a no-nonsense road," asserts Eastwood. "His extravagances came out several pictures down the line. There was no reason it shouldn't be on time," says Eastwood. "To go in and do one shot after lunch and another one maybe at six o'clock and then go home is not my idea of something to do. I like to move along."

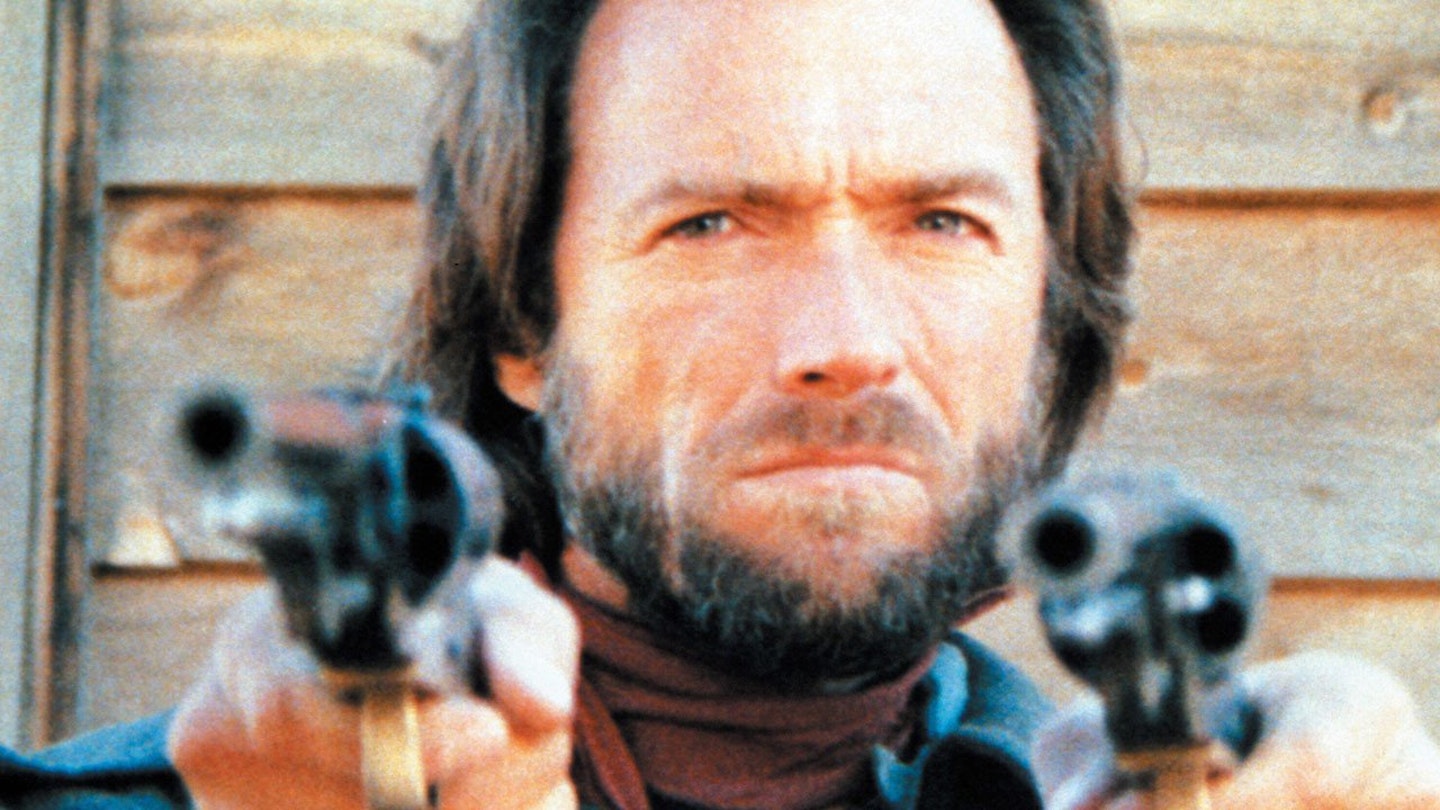

The Outlaw Josey Wales

1971, Clint Eastwood

"When people stop me in the street, it tends to be about Josey Wales," says Eastwood as if the idea of anyone stopping anyone in the street baffles him. "They seem to like that one. I rented it recently, it still holds up."

Alongside Unforgiven, the grand conclusion, The Outlaw Josey Wales is arguably Eastwood's greatest contribution to the Western, the genre he wears across him like a poncho. In fact, alongside the Johns Wayne and Ford, he is the greatest exponent of American folklore on film, but as Josey Wales reveals, he plays the game differently to those classically minded partners. "The Spaghetti Westerns had a very stylish feel to them, and caused some attention and certainly go me started," he explains, "but Josey Wales was the first script I really liked."

When people stop me in the street, it tends to be about Josey Wales.

He had been startled by Forrest Carter's novel (entitled Gone To Texas), a vengeful tale of a farmer who turns guerrilla fighter after his family is massacred in the sunset of the American Civil War, and commissioned Philip Kaufman to write the script. Kaufman turned in an astonishing piece of work, as much a war movie as a cowboy jaunt, at points starkly real at others romantic even mystical. Kaufman was due to direct, but Eastwood replaced him at the eleventh hour. "It was a difficult time, creatively," he says furtively. Perhaps, he finally knew Josey that much better.

"There was stylishness in it too, you felt anything could happen," he says. Josey is on a journey to rediscover his humanity within the psychotic whirl of his life, but rather than mordant the film is lit-up by a Leone-like humour and a Siegel-like edginess. "It's a picture I'm fond of," allows Eastwood humbly. You won't catch him boasting.

Josey Wales is also celebrated as allegory - a direct reference to the shadowy decline of Vietnam, all but a defeat by 1976. "Well, a lot of people write that," he sighs, never comfortable dwelling on potential 'meanings' in his films. "You should be able to read movies I guess, read into them what you see, and this was made in the Vietnam era. I did see it as allegorical, but it is as much about the Civil War, one of the most bloody and impactful in American history because it pitted American against American." He pauses to regulate his answer: "It was about a man with a disappointment about that." Who could put it any better?

Every Which Way But Lose

1978, James Fargo

"It was not quite the thing people were expecting," laughs Eastwood knowingly. Indeed, the two 'ape movies' stand out of his career like a temporary loss of sanity – what the hell was he thinking? "No one was particularly excited about it. It had nothing to do with Dirty Harry."

Which is exactly why Eastwood, at the peak of his box office appeal, elected to star alongside an orang-utan named Clyde (in reality a diffident ape named Manis) in a knockabout comedy originally intended for Burt Reynolds: to confound expectations. "Anytime anybody tells me the trend is such and such, I go in the opposite direction," he explains. "I saw it as some camp deal, there was something about the screenplay that was unusual. I mean it was about this fringe society where there is bare-knuckle fighting."

The film is an oddity certainly, yet as directed by James Fargo (another regular compatriot) it retains something of the laconic but morally sturdy Eastwood vibe - this offbeat corner of America where a tight knit community rubs up against the system. Even if it does centre on a touching relationship between a big heap of a boxer and a good-natured orang-utan.

"You have to be able to shoot really quickly because the ape has the same concentration as a seven year-old. One take and they are fine, two and their mind is running off somewhere. You have to be ready to roll."

And just to confound the nay-sayers the film, initially deposited in small-town cinemas to make room for Warner's big 1978 release Superman, was a smash hit precipitating a sequel (the rougher, sillier Any Which Way You Can) and defining Eastwood as a star capable of loosening the screws a little and, get this, appealing to kids. "It turned out to be this PG kind of movie," he says approvingly, "one that could reach down to an audience I hadn't been appealing to with the tougher pictures."

Escape From Alcatraz

1979, Don Siegel

“We know from other people inside how it was all planned, you can pretty well retrace the whole story," marvels Eastwood. "What happened to them when they got off the island, of course, nobody knows."

The story goes that no one ever officially escaped from Alcatraz, but in 1962 con Frank Morris and two others disappeared through tunnels hewn out with cutlery and got off the island on rafts made of inflated raincoats. The authorities say they drowned, but no bodies were ever found. One of the strange things about the current enshrinement of The Shawshank Redemption is how rarely anyone recalls that Stephen King lifted most of his plot from this hugely underrated 1979 teaming of Eastwood and Don Siegel, their final work together. "By that time I had known him a long time so we had a good shorthand. He also tended to like the stuff I liked. It was simple."

It's the sparest and hardest of the Siegel-Eastwood collaborations, pruned of all but the most essential detail – we learn nothing about who these characters were before they came to Alcatraz, just as we never find out what happened after the 'escape'. Eastwood, at his most iconic, is Norris, the only man tough enough to beat 'the rock' (he also, in an extreme long-shot, does his only full-frontal nude scene), while Patrick McGoohan makes a subtle megalomaniac who takes steps to crush even the dreams of his prisoners. Siegel - shooting on the concrete, rusting, brutal hulk of the Rock itself - takes things slow and steady. "The authorities were pretty good to us," recalls Eastwood. "The only odd thing was that Indians had occupied the place in the '60s and sprayed graffiti all over the place and they said, 'You can't touch that graffiti, it's part of the history', and I said, 'Wait a second – tourists weren't going over there to see a lot of graffiti, they were going over there because Al Capone and was housed there.'" He got his way.

A Perfect World

1993, Clint Eastwood

"I just like smaller stories and interesting people," says Eastwood without apology. "I thought it was an interesting role for Costner, something he hadn't played before, someone who had a slightly bent personality and he wanted to do it badly and I thought he did a terrific job."

The news that Kevin Costner, neophyte prince of the Western, would be sharing the screen with Eastwood, grand old man of the saddle, was greeted in some quarters like the second coming. Surely it would be a sprawling Western in the great tradition, enhanced by both their qualities. A studio dream of a high profile, cross-generational team up.

Naturally, Eastwood didn't go that way at all. This small, almost leisurely road movie, about a con bonding with the small boy he kidnaps where the two male stars barely share the screen, left most nonplussed. Eastwood only appears at all when Costner suggested he was a perfect fit for old Texas Ranger on his trail, and the director had originally wanted Denzel Washington.

Allowed time to mature, it is viewed as a minor classic. Eastwood is right, Costner is terrific, and the film possesses the warm heart and lean, dusty depiction of small-town America that have become part of the Eastwood aesthetic (to a lesser degree look at Play Misty, Honky Tonk Man, Pink Cadillac and Million Dollar Baby).

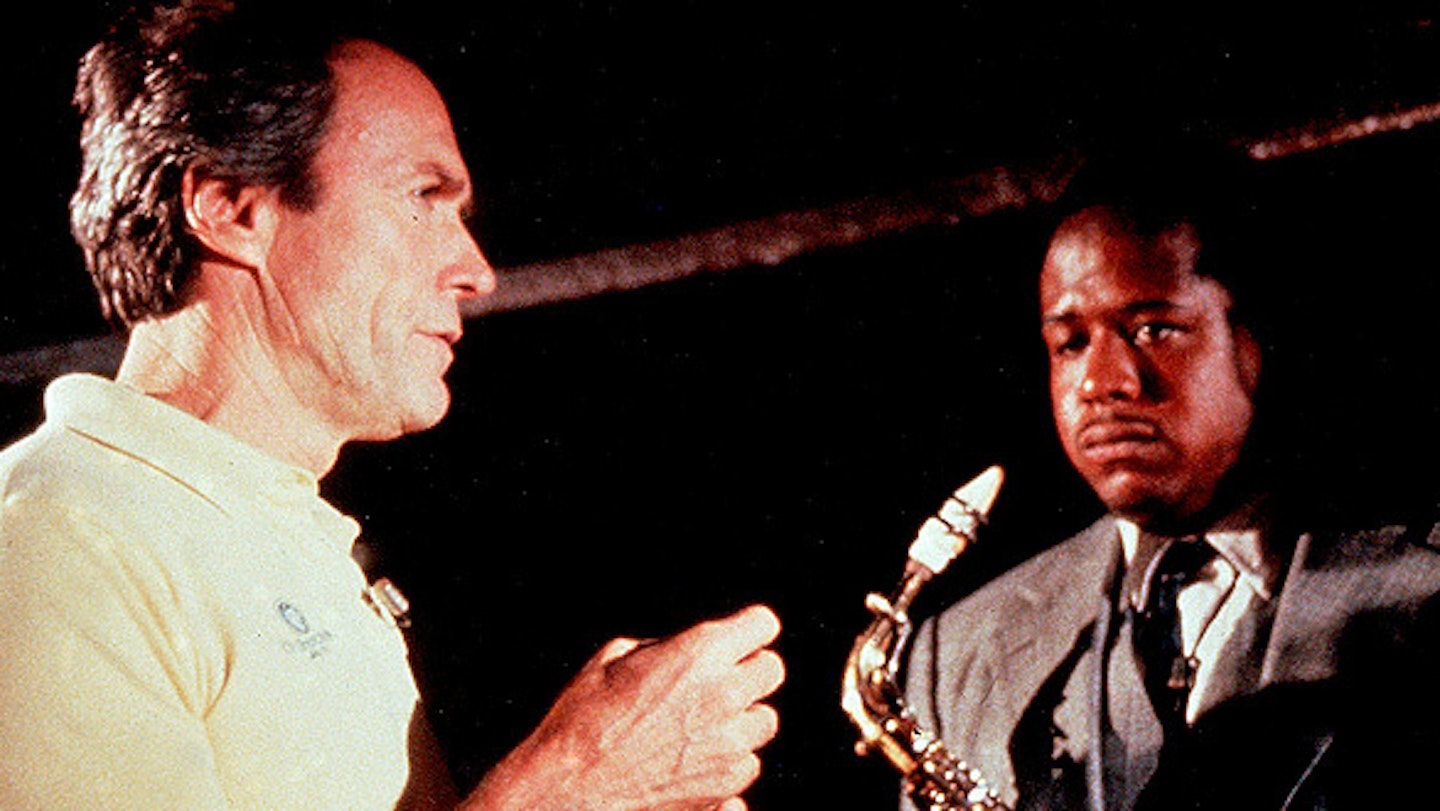

Bird

1988, Clint Eastwood

"I always remember seeing Charlie Parker when I was a teenager growing up and how impressed I was with his playing and I've read a lot of material about him over the years, so I had some insight into his life."

Eastwood opens his biopic of jazz great Charlie 'Yardbird' Parker with a quote from F. Scott Fitzgerald, 'there are no second acts in American lives.' When Parker died at 34, from the effects of decades of heroin use, the coroner assumed he was a man in his sixties. Folks who had caught too many orang-utan movies were surprised to learn that Eastwood the director had even heard of F. Scott Fitzgerald, let alone Parker. It seemed in 1988 like an astonishing break with his previous career to make a movie, only the second film (after Breezy) he directed without taking a star role, with more saxophone solos than gunshots on the soundtrack. However, Bird was a personal project, and indicated that the life of Clint Eastwood the director was entering a second, if not a third, act.

"I went in regardless of what it was," he says, never perturbed by immediate commercial issues. "I was interested because of my love for the jazz of that era. The '40s saw one of the great harmonic changes in the music – a lot of the audience had to work hard to catch up to it and appreciate it."

A lifelong jazz buff, Eastwood had seen Parker perform in Oakland in 1945 and took great steps to obtain the rights to Joel Oliansky's script. It was originally set up at Columbia as a Richard Pryor vehicle, but when that fell through the studio gave it to Eastwood and Warners in exchange for Revenge, which Eastwood had been set to direct. Bird follows the chubby, charismatic hornman (Forest Whitaker, who won Best Actor at Cannes for the role) through a stormy interracial non-marriage to Chan (Diane Venora), upon whose memoir the script was based.

The film also demonstrates a sensitivity and depth of feeling that had always been present in his work as a director, as well as that streak of individualism that makes him unique. "I didn't know how commercial it'd be, but I knew I could make a decent movie out of this. The studios I work with, all I can promise them is the best movie I can make. What life it has after that depends on fate."

Unforgiven

1992, Clint Eastwood

"I can give you a pseudo-explanation, loading up a bucket of psychobabble," groans Eastwood, forced into taking a deeper look at his Oscar-winning masterpiece. "I felt like that was the genre I became known in, it had been so good to me, and that this would be the perfect last Western for me, and so far it had turned out that way."

He might hate the reading of his movies, but you can feel the hand of destiny on Unforgiven - it was the perfect swansong to a genre. Grafted into David People's rich, multi-faceted study of an ageing gunfighter dragged out of retirement, only to unleash the demons of the past, was a commentary on Eastwood's own career as if it had been written solely for him. Within his wire-frame William Munney carries the soul of Leone's Blondie, of Josey Wales, and all the other pale riders of Eastwood's history.

Without sounding like a pseudointellectual dipshit, it's my responsibility to be true to myself.

When he picked up the script in 1980, even then he couldn't miss its resonance, and promptly sat on it for decade until he was old enough to make it live. "It had been in preparation with another director, but he couldn't get it off the ground, so I dropped in on the auction and put in a drawer. I remember calling the writer all those years later, he thought it'd long been dead, and I asked for a few rewrites, made a few suggestions."

It's a trait of Eastwood to obsessively circumvent potential bullshit. He talks everything into the humdrum - how he'd been skiing with his son in British Columbia and thought it would make a good location for the movie; how everything slipped into gear so easily. "We put the town there and went ahead and shot the film." Just like that, one of the greatest Westerns ever made.

A year later, under the lantern gaze of the Academy Awards, he was rewarded with Best Director and Best Picture victories. Trust Hollywood to be so late in awakening to the gifts of one of their masters. "It was very nice," understates that master. "Westerns are not known for being Oscar winners historically; a lot of great ones have not got recognition, so that made it doubly gratifying." Not coincidentally, the film was dedicated to Don and Sergio.

In The Line Of Fire

1993, Wolfgang Petersen

"I'd just finished Unforgiven and didn't want to direct a picture so soon, but I really liked the material," recalls Eastwood. "So I said, 'Well, let me pick a director and I'll do it. I had just seen a picture by Wolfgang Peterson called Shattered. I thought I've always had good luck with American subject matter using European directors and, of course, Das Boot was a wonderful movie."

Coming so shortly after Unforgiven, this excellent thriller, given genuine punch by Peterson, was by chance a perfect companion piece to the elegiac Western. Again it focuses on the issue of age, of a presidential bodyguard who has got wind of a possible assassination attempt being cooked up by John Malkovich having a ball as the psycho with a personal vendetta. And it is Eastwood's last great turn as an action star that sticks with you: huffing and puffing alongside the motorcade, a superstar revealing an unusually vulnerable side.

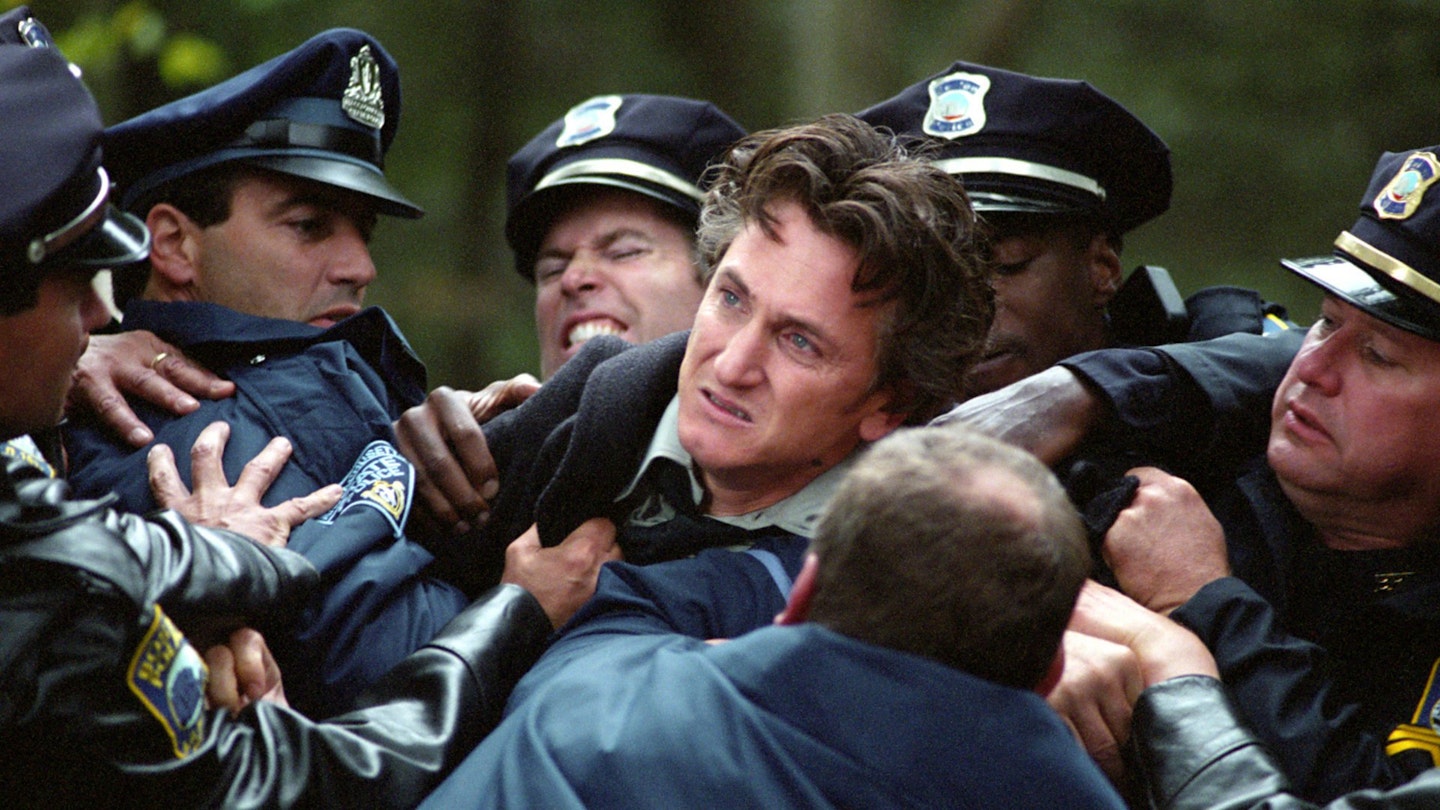

Mystic River

2003, Clint Eastwood

"No one was too excited about Mystic River – they thought it was too dark, they couldn't see it." Even for the those committed to the Eastwood cause raised eyebrows when he chose to adapt Dennis Lehane's grim tale of child abuse and murder in a backwater district of Boston. It didn't feel, well, very Clintish, and he wasn't going to be in it - Sean Penn (who one Best Actor for his performance as a local hoodlum), Kevin Bacon and Tim Robbins were the three friends who share a painful past, which echoes into the present.

Eastwood, however, could feel the reach of the material - it spoke as much about America's insular communities as it did about cops and crime and it remains possibly his darkest piece. "You can't second guess yourself," he says of his own determination. "You can find a million reasons why something doesn't work. Without sounding like a pseudointellectual dipshit, it's my responsibility to be true to myself."

Million Dollar Baby

2004, Clint Eastwood

"I gave it a read and I liked it right away, so I called up Paul Haggis and said, 'Yeah I'd like to direct it and I'd like to act in it, and if you could set that up I'm ready to go.'" Indecision, something of a plague in Hollywood, has never exactly afflicted Eastwood. He is a man of certainty. And having read F.X. Toole's gripping short stories set amongst the seedy world of amateur boxing, and then Haggis' gritty adaptation of this poignant tale of a female boxer trying to better herself, well, that was that. "People often say I'm a fast director," he laughs softly. "I'm just decisive."

However, Warner, his home studio, were lukewarm. They were loathe to let him down, but did it have to be this? "They said, 'No boxing movies have done well in recent times and a woman boxing has never done well,'" says Eastwood. "I said, 'You know it's not really a boxing movie at all. It's a love story about the father that she never had and the daughter that he never had - two people alone in the world, that becomes a love story."

Eastwood, unbowed by Warner's reluctance, did a tour of the other studios where he was uniformly met by polite reluctance. Boxing? Female boxing? Are you sure? "They would be like, 'Uh, we were thinking more in terms of Dirty Harry coming out of retirement.'" Finally, with a mind to the legacy of their relationship, Warner agreed to a budget of $30m. Off Eastwood went, accompanied by Morgan Freeman and Hilary Swank, and with typical lack of fuss made his movie. " Then it was like, 'Well why don't we just put it out and see if anyone likes it. It kinda found its own life."

This savagely emotional drama, featuring among its many pleasures Eastwood's finest performance, ended up beating the hot favourite - Martin Scorsese's The Aviator - to the big Oscars. The film took home Best Picture, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actor and Eastwood's third directing nod.

Changeling

2008, Clint Eastwood

"It's a story that takes place in Los Angeles in 1928 about a woman who's child goes missing so she tries to get the police department, which was very corrupt at that particular time, to do more," says Eastwood. Loosely based on real events, the drama hinges around the point the child is found, when, amid a media frenzy, she realises it is not him. "They keep telling her she's crazy. They try to sort of bend her mind, to tell her that she's hallucinating. Remember the picture Gaslight? (an atmospheric George Cukor drama of 1944, starring Ingrid Bergman), I've gone for that feel. It's quite dramatic."

This was new territory for the ever versatile director, a noirish period drama with shades of LA Confidential (its overriding theme is police corruption) but perhaps with a more thought-provoking attitude as it examines the sexual politics of the Prohibition era - a time when women were not supposed to be outspoken. The distraught mother (Angelina Jolie), becomes the subject of a campaign of slander fomented by a secretive police department.

Having Jolie as your lead certainly gives it a provocative edge, and Eastwood couldn't be more thrilled with the outcome: "She's wonderful, she's wonderful," he beams like a proud father. "To me it's like she's a throwback to the women in film of the '40s. Not to say the women today aren't great, but back then there was more individuality, all the faces were different, they didn't have to same Botox look. Angelina has that great individuality, her own look and her own style and she's a terrific actress besides. I think she would have been just as big a name in that era than, the same as Katherine Hepburn and Bette Davis and Ingrid Birdman." In her turn Jolie found working with the esteemed Clint Eastwood a stimulating experience: "You've got to get your stuff together and get ready because he doesn't linger...which I think is wonderful. He expects people to come prepared and get on with their work."

This article first appeared in Empire magazine issue #229 (July 2008).