Roger Deakins

The great Roger Deakins CBE is the man who made Skyfall shimmer like no other Bond movie, whose stellar work with the Coens began with Barton Fink ten Joel-and-Ethan movies ago, and who currently has 11 - count 'em - Oscar nominations to his name.

Beloved of directors and all of his fellow cinematographers, it's safe to say he's high on the Christmas card list for most of the actors he's lit, too. "Sometimes you get a cinematographer who shoots something, and you walk into their light, and they're doing 50 per cent of my job," Jake Gyllenhaal recently told The Hollywood Reporter. "I walked into Roger Deakins' lighting in two different movies, and I didn't feel I had to give a performance." The Academy has agreed and included his work on Prisoners in this year's Oscars shortlist.

In short, Deakins is a giant of his field. He spoke to Empire from Sydney, 10,000 miles from his native Torquay, where he was working on Angelina Jolie's wartime drama Unbroken.

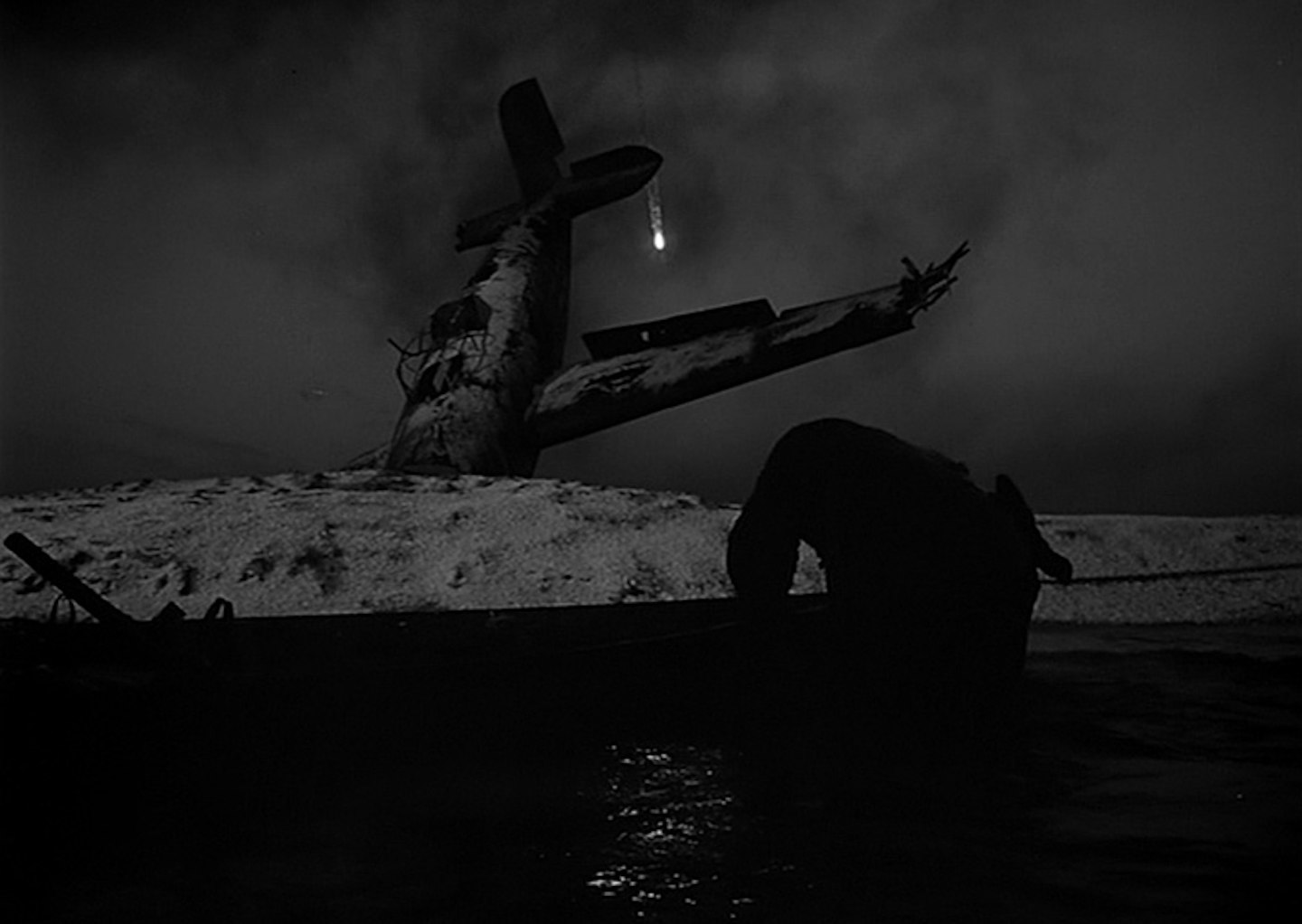

The Shot: Ivan's Childhood (1962)

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

Cinematographer: Vadim Yusov

I don't know how to pick just one shot - I guess it depends on what mood you're in that day - but there's a shot in Ivan's Childhood where the boy is crossing between the German and Russian lines that I absolutely love. It's this incredible black and white landscape, illuminated by flares like a kind of ghostly hinterland, with this downed fighter plane jutting out of the earth. I don't know what camera Vadim Yusov shot with in the water, but I'm sure it was a lot heavier than the ones we use now. He also shot Solaris for Tarkovsky, which is also a remarkable-looking film. Yusov died recently - I was sad not to have been able to meet him.

Antonioni's films always had beautiful cinematography - L'Eclisse, Red Desert, The Passenger. There's this beautiful sequence in L'Avventura where Monica Vitti and Gabriele Ferzetti stop in an abandoned town and the camera tracks down this deserted street.

I'm in Australia at the moment and have rewatched On The Beach (shot by Italian great Giuseppe Rotunno), which is set here in the aftermath of a nuclear war. There's a shot where Gregory Peck, an American submarine commander, surfaces off the coast of San Francisco to see what's left and it's just nothing. Emptiness. It's simple but beautiful.

Ben Seresin

New Zealander Ben Seresin has shot for Tony Scott (Unstoppable), Michael Bay (Transformers: Revenge Of The Fallen) and Gore Verbinski (Pirates Of The Caribbean: At World's End), which means he's probably filmed more explosions than we've had hot dinners. More recently, he photographed World War Z for Marc Forster, a production he describes with Kiwi understatement as "challenging", and Pain & Gain for Bay. Picking a single shot for this piece is a task he likens to choosing his favourite food. "I have a million favourites, and all for different reasons!"

The Shot: I Am Cuba (1964)

Director: Mikhail Kalatazov

Cinematographer: Sergei Urusevsky

What most interests me is the power of cinema and the opening shots of I Am Cuba have an authenticity and beauty that's unique. In some ways, it's a pretty inaccessible film - it's 50 years old, culturally very different and super-stylised, but the opening sequences show the power of filmmaking to transport you. There's no acting, and when the acting does start it's pretty flawed, but you really feel like you're there. You can touch and taste the atmosphere. It's visceral.

The opening is a fairly straightforward helicopter shot over the treetops, using almost a fixed camera locked in a three-quarter angle. Then the camera is mounted on a boat and it's a guy heading downriver, with the camera rigged at foot-level. It's a very wide angle, almost fish-eyed but not distorted, and it's beautiful considering how old the technology is. Then it's on a rooftop with a band playing, and the camera goes down in a crane or lift and follows people into the swimming pool and underwater. The filmmakers spent days and days building these complex, Heath Robinson contraptions to transport the camera, and apart from that opening shot the camera is always very close to whatever it's shooting. I have no idea how they did it, but it's very powerful. If a shot doesn't connect you with the story or move you in another way, it hasn't done its job.

Is Michael Bay a fan of I Am Cuba? No, he would 100 per cent not be a fan of I Am Cuba. He's a fantastically talented guy and I've talked to him about films and references, but in the context of work they have to fit into his very particular style. He's not someone who sits around talking about old movies.

Laurie Rose

It's always a challenge," Laurie Rose says of his filmmaking partner-in-crime, Ben Wheatley's, fast-and-furious MO. "He pushes me to do my best." The results, a four-film run of twistily brilliant Brit flicks, kicked off with the week-long Down Terrace shoot in their native Brighton ("A bit mental," laughs Rose of a feature film that was virtually miracled into existence) and, most recently, offered the stark, monochrome beauty of A Field In England.

Most recently he shot Nick Frost salsathon Cuban Fury. "I've never made a decision to be a 'cinematographer' as such," he told Film Doctor. "It's a peculiar word that I don't entirely identify with and never call myself. It sounds way too grand for me.

The Shot: Hunger (2008)

Director: Steve McQueen

Cinematographer: Sean Bobbitt

No single shot defines cinema for me. That's the joy of it - the possibilities. On a technical level, I love and appreciate the sense of achievement of the 'impossible' shot, that 'how-the-fuck-did-they-do-that?' moment made possible by the evolution of technology - the 'toys' - combined with choreography and intense planning. The car interior in Children Of Men or the flying shots in Hugo. But most of all, I love the simple shots that anyone might achieve with a bold idea. Jaws' contra-zoom, dating back to Vertigo, is a mind-blowingly simple optical effect that throws your world into disarray, creating a moment of epiphany, of fear. By contrast, I Am Cuba defies these ideas. And to achieve those shots at that time? It's inspiring.

I'm fascinated by a performance that can be so strong it defies the received grammar of an edit, even cinema itself. Does that make it theatre? Hunger's 20-minute prison dialogue between Michael Fassbender and Liam Cunningham is a triumph. The performance carries the scene, it doesn't need an edit. It's really bloody bold. We're in that room, but we're not taking part in the dialogue - it's their conversation. But I'm not sure this shot, or any single shot, can really exist in a vacuum outside of the context of the story. You need to have a relationship with what they're talking about, and perhaps to know a little of the characters and their relationship to each other. If Hunger consisted of just that scene, it would be theatre. As one scene within the whole story? That's cinema.