With Carol (in cinemas from today), director Todd Haynes has produced the best-reviewed film of his career. A simmering, sumptuous story of a love that dare not speak its name, Carol features yet more indelible examples of a Haynes character: all memorable, all mesmerising, all fascinating, all flawed.

With this in mind, we sat down with Todd to talk about the most unforgettable characters from across his films, what drew them to him in the first place, and why.

Carol Aird (played by Cate Blanchett)

Carol, 2015

In 1950s Manhattan, Carol Aird has an outwardly perfect life: a rich husband, a loving family, a glamorous place in New York society. But she harbours a love for women, at a time when homosexuality was considered obscene.

Carol is a remarkably frank and uncomplicated character. She never has to be that clandestine about her feelings for women. I mean, she’s not French-kissing in the street, but she never has to do anything out of character. That said, beneath that mostly seamless surface – her manner, her elegance, her beauty – there’s something slightly neurotic.

There’s little hints of someone who’s not happy.

There’s little hints of someone who’s not happy. Some of these moments resound in the background. She looks like somebody who would never get nervous, but then she confesses to always feeling nervous in a department store. I wanted to mark a few places where you sense something unhappy in this woman.

I feel like this is an interesting thing about desire. People find themselves pursuing desire, not only against their better judgement, but against their own taste! You sometimes get a crush on somebody that kind of bugs you. I love that. There’s something so much more interesting about that than the boring, effortless perfect romance. I think there are all these interesting ways that ambivalence gets expressed behind the Carol’s facade.

Carol’s glamour is obviously something she’s learned. She’s a beautiful woman, but she knows how to dress, and move, and behave in a way that has gotten her to this place. In the book, you learn that she wasn’t born into this class; she acquired that discipline and that self-presentation that has a certain societal value. And yet: she’s done all the right things, but it hasn’t led her to contentment or happiness. So she looks elsewhere.

Therese Belivet (played by Rooney Mara)

Carol, 2015

While Carol has come to terms with her sexuality, Therese – a young shopgirl – is still getting to grips with hers. When she unwittingly befriends an older woman, she embarks on a hugely formative affair.

For me, it doesn’t even matter if Therese is genetically gay or could only feel the way she feels for a woman. It seems like it’s also due to circumstance and the accident of life that this affair happens. Who knows? Maybe the only kinds of love she could ever feel was for women. But there’s something unformed about her, and we’re watching it take form, and also watching an incredibly powerful accidental relationship emerge, so unexpectedly. It’s such an unlikely pairing, these two women, of such different ages, different socioeconomic worlds – the tenuousness of it all makes it feel so fragile. But the reciprocal little strands of desire grow, and fortify, and deepen, and all of these things happen almost outside of Therese’s will. This is very much a human predicament.

She has a fascinating arc. She grows up. She gets hurt. She develops defences. She learns about survival and self-protection, and that means she will go on in some direction or other. She won’t just be completely crushed by life. But it also means that she’s not that same person who Carol has simultaneously reevaluated at the start of the film.

Harge Aird (played by Kyle Chandler)

Carol, 2015

Harge, Carol’s husband, represents the old world. But he is also essentially a jilted lover, left to pick up the pieces of a broken family.

He’s not just a stock homophobic villain. This started with Phyllis’s first draft. He’s treated much more harshly in the novel, but Harge is given dimension in the script, which I really liked. You really feel for him, and he is actually behaving fairly decently, given who he is, what his options are, what he might know about the world. It also helped that the performance from Kyle Chandler – with such economy, he’s only in a few short scenes – he is already a changed man from the point we meet him. We already see that his marriage is falling apart, and we see him reevaluating how important it is, and you feel like he’s taken her for granted.

Cathy Whitaker (played by Julianne Moore)

Far From Heaven, 2002

In Haynes’ gorgeous tribute to the classical Hollywood melodramas of Douglas Sirk, Julianne Moore plays the unflappable Cathy Whitaker, a consummate 1950s housewife of a nuclear family. But her perfect homelife comes under threat from a gay husband and her own romantic feelings for an African-American man.

I was thinking a lot about how that tradition of the Sirkian melodrama works. What Sirk did so beautifully was to create an entanglement of conflicts, where there’s no villain, where one person takes one step towards their desire, or one step out of prescribed behaviour, and everybody suffers as a result, and you just feel the constraints of society tightening on them as a result. That was what I tried to construct in Far From Heaven – it’s almost like a diagrammatic crisis where people’s lack of freedom is shown in a diagram.

It’s really the story of a woman trying to maintain the institution and the integrity of family.

I was very interested in taking the less predictable position with Cathy. Frank is a somewhat distant character – we only get little glimpses of what’s happening to his life. If we spent any more time with him out on the prowl, it would have just tipped the movie into “gay man coming out in the ‘50s” territory. It’s really the story of a woman trying to maintain the institution and the integrity of family. You don’t really think Cathy is going to run off with Raymond. There’s a limit to how far she’s going to go. She’s just looking for some kindness, and in her world, it’s very hard to trust anybody to understand what’s going on with her and her husband. Even Raymond never gets the full story. People try, in these really tiny ways, to just survive basic human dilemmas. You ultimately watch them buckle under the pressure of it. They’re not being heroic – they’re people compromising. as best they can.

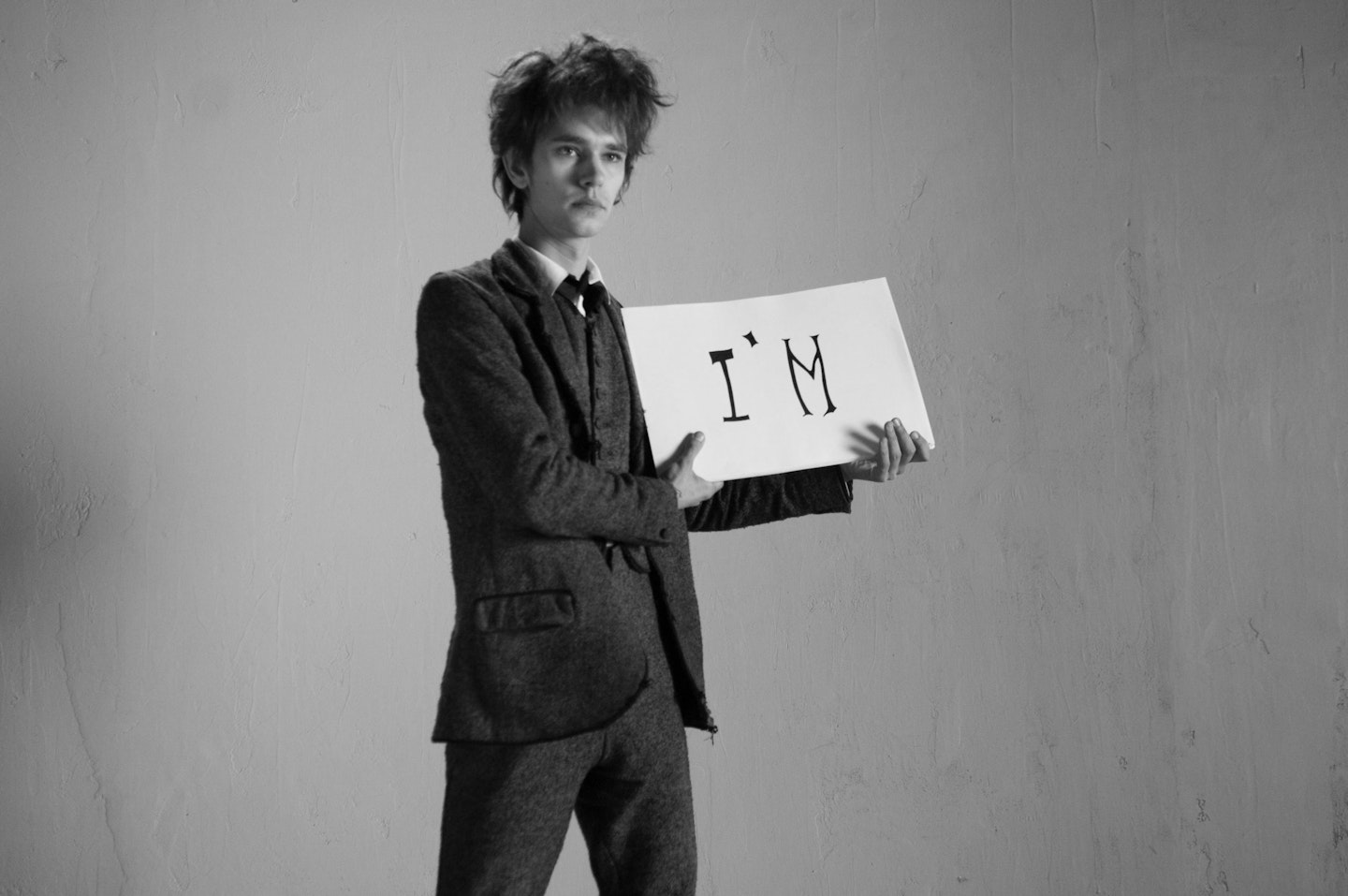

Bob Dylan (played by Christian Bale, Cate Blanchett, Marcus Carl Franklin, Richard Gere, Heath Ledger, and Ben Whishaw)

I’m Not There, 2007

The mythology of Bob Dylan is expressed in six separate characters, portraying six key eras of the folk hero’s career, in this unique, impressionistic experiment.

I read a lot about Bob Dylan. Every account I read of him from the 1960s said that he would plummet deep into an idea, create all of this iconic work that everybody loved, and then, as soon as everyone loved it, he had to move onto something else. In the hyper-condensed climate of the 1960s, under that extraordinary burden of success, he sometimes he had to do some really radical things to keep the air fresh around him. Ultimately, he just needed to keep making things and keeping himself interested. He didn’t need to prove himself anymore. He just had to keep feeling excited by the work. That meant continually upsetting his followers.

Even now, he keeps reinvigorating himself. I thought that pattern exposed a practice around notions of being fixed - about identity as something that stays stable. and that through artistic expression, you’re supposed to keep affirming something, returning to something, or proving yourself to be something authentic, and the result, whether intentional or not, was that nothing stayed authentic. In a brilliant way. Authenticity is not the point. Americans, in particular, get hooked on this idea.

Brian Slade (played by Jonathan Rhys Meyers)

Velvet Goldmine, 1998

Earlier in his career, Haynes took another fablistic look at a musical icon, with the fictional character of ‘Brian Slade’ acting as a proxy for David Bowie, told in a surreal, hypnotic flashbacks.

It was always key to keep a sort of mythological distance here. That’s why the Citizen Kane structure made the most sense to me. I just thought: he has to be an object of everybody else’s projections, and distortions, and differing points of view. When you presume to be intimate with a famous person, you get bogged down in trying to tell the truth, trying to reveal what really happened behind closed doors. There were plenty of men who had affairs with Bowie, but what’s so interesting about him is that it doesn’t really matter whether he really was gay or not.

What’s so interesting about [Bowie] is that it doesn’t really matter whether he really was gay or not.

That’s what he used in his art. That’s what he used as a language, to distinguish himself at the time, to completely shock and astound people, and to set up a whole new set of conventions that all of a sudden became the norm. By doing so, he completely rewrote the narrative of masculinity and heterosexuality in rock ‘n’ roll.

In a way, the traditions around gay articulation like Oscar Wilde and others who preceded him were all about elevating artifice and illusion, and again rejecting the notions of stability authenticity, in the most witty, colourful, artful sort of way – whether through literature, or rock ‘n’ roll, or theatre, or film. When I approached this story, this character I just thought: wow, not only someone whose work I admire, who changed my life, but what a radical narrative to bring into popular culture, even for one little moment.

Carol is now showing in UK cinemas.