“Carlo Rambaldi was E.T.'s Geppetto,” recalled Steven Spielberg about the Academy Award-winning special-effects artist who passed away on Friday. Rambaldi’s craft mixed mechanical, electronic and systems design engineering but his art knew limitless imagination, winning Oscars for King Kong, Alien and his most famous creation E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial. In an age of colourless, characterless CGI creations, Rambaldi’s work runs the gamut from sheer terror to benign wonder but always with personality. Here are some of his highlights over his 30-film career.

Born in Vigarano, Italy in 1935, Carlo Rambaldi studied as an artist at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna. He entered the film industry in the ‘60s as a prop man working on flicks such as Barrabas, The Bible and Barbarella, co-creating the vicious mechanical dolls that smack Jane Fonda to life using the kind of cable controlled mechanical devices that became his trademark. His work in Europe saw him work for viscounts of violence Dario Argento (Deep Red — Rambaldi created a scuttling automaton), Andrzej Żuławski (Possession — this time round a tentacled creature) and most notably Lucio Fulci. For A Lizard In A Woman’s Skin (1971), Rambaldi created vivid scenes of dog mutilation so realistic that Fulci was prosecuted for offences relating to animal cruelty. Fulci was facing a two-year prison sentence until Rambaldi showcased his creations to a court proving no animal was harmed during the making of the production. It is the first case of a special effects artist legally proving his work is not “real”.

Italian impresario Dino De Laurentiis was a huge fan of Rambaldi’s work and sought the artist out to work on his US reboot of King Kong. Rambaldi was commissioned to design the title star and ended up building a 40-foot mechanical gorilla. The stats are mind-blowing: a 3.5 ton aluminum frame + 1,012 lbs of Argentinian horse tails (sewn individually into place) + 2 x 6ft across hands + two arms weighing 1,650 lbs each + 3,100 feet of hydraulic hose + 4,500 feet of electrical wiring + 20 operators = $1.7 million. The scale of the creature was dictated by the size of the hands — Jessica Lange had to sit comfortably in the palms — and it remains the largest mechanical creature ever created for a film.

The hands became a beast on their own. Made out of duralumin metal, the monster’s mitts were inserted with bolts in the knuckles to stop them closing too tightly, then covered with rubber and the ubiquitous Argentinian horsetails. In themselves, they took four months to create. When they were finished, De Laurentiis came to visit the set, the crew extended the maws in the producer’s direction, then slowly uncurled the middle finger into the standard Sit And Swivel position. De Laurentiis cracked up but the laugh rang hollow: the mechanical finger froze in the upright position for around five days.

Yet for all the on-release hoopla around the great ape, Rambaldi’s creation only appears on screen in its entirety for under a minute, the monkey business mostly performed by a man in a Rick Baker suit. Still Rambaldi’s work on Kong is a huge stepping-stone in the advancement of animatronics-style effects.

As well as the 40 foot mechanical ape, Rambaldi had mechanically enhanced a series of masks created (and worn) by Rick Baker. Steven Spielberg saw the movie and was impressed by the level of articulation and contacted Rambaldi about creating the aliens that emerge from the mothership at the end of Close Encounters. Spielberg had tried numerous different techniques — chimpanzees on rollerskates, children in alien suits, Muppet-style rod puppets, marionettes — but nothing had come close to providing the level of sophistication needed to deliver his ET emissary, nicknamed 'Puck' by the director. Rambaldi constructed the character in Rome and brought the character to the US when he attended the Oscars to pick up a special award for King Kong.

By this time, Close Encounters had wrapped principal photography, and, on May 20, Spielberg reassembled Bob Balaban and Francois Truffaut on a Burbank soundstage and revealed his alien. Fashioning a skeleton out of aluminum and steel and a skull out of fiberglass, Rambaldi added mechanisms that facilitated arm, hand, head and eye movement operated by fifteen thin flexible cables that run down Puck’s body. Rambaldi added quarter-inch thick polyurethane skin but only just before shooting as it decomposed rapidly. It took a crew of seven operators to bring the ET to life, air pumping through the chest to add realistic esophagus and breathing motions. Puck performed the five hand signals perfectly and, when it came time for him to smile, Spielberg himself operated the levers to produce that beguiling grin.

If Rambaldi didn’t contribute to the design of Ridley Scott’s xenomorph — that belongs to H.R. Giger — he made huge contributions to the film, creating the creature’s dome shaped head. Rambaldi followed Giger’s designs closely deviating only to incorporate points of articulation for the jaw and inner mouth. Overall the head boasted 900 moving parts, a nexus of hinges and cables operating the tongue that extends from a mouth that played host to a second mouth with a movable set of teeth. Still, for all the sophistication on show, Rambaldi used a simpler process to generate alien saliva: copious amounts of KY jelly doubled as both saliva and the Alien goo that gives the creature its distinctive slimy sheen.

Still, for Rambaldi, the finished film only showcased a fraction of his creature’s capabilities. “They use all the movements, but the head cuts are so quick, and the action is framed so predominantly in extreme close-up, that frequently it's impossible to tell what you are seeing! In my opinion, I gave the director 100 possibilities, and he used but 20.” Still, whatever Rambaldi thought of the film’s editing, it didn’t preclude his creation becoming iconic: his Alien jaw is currently on display at the Smithsonian Institution.

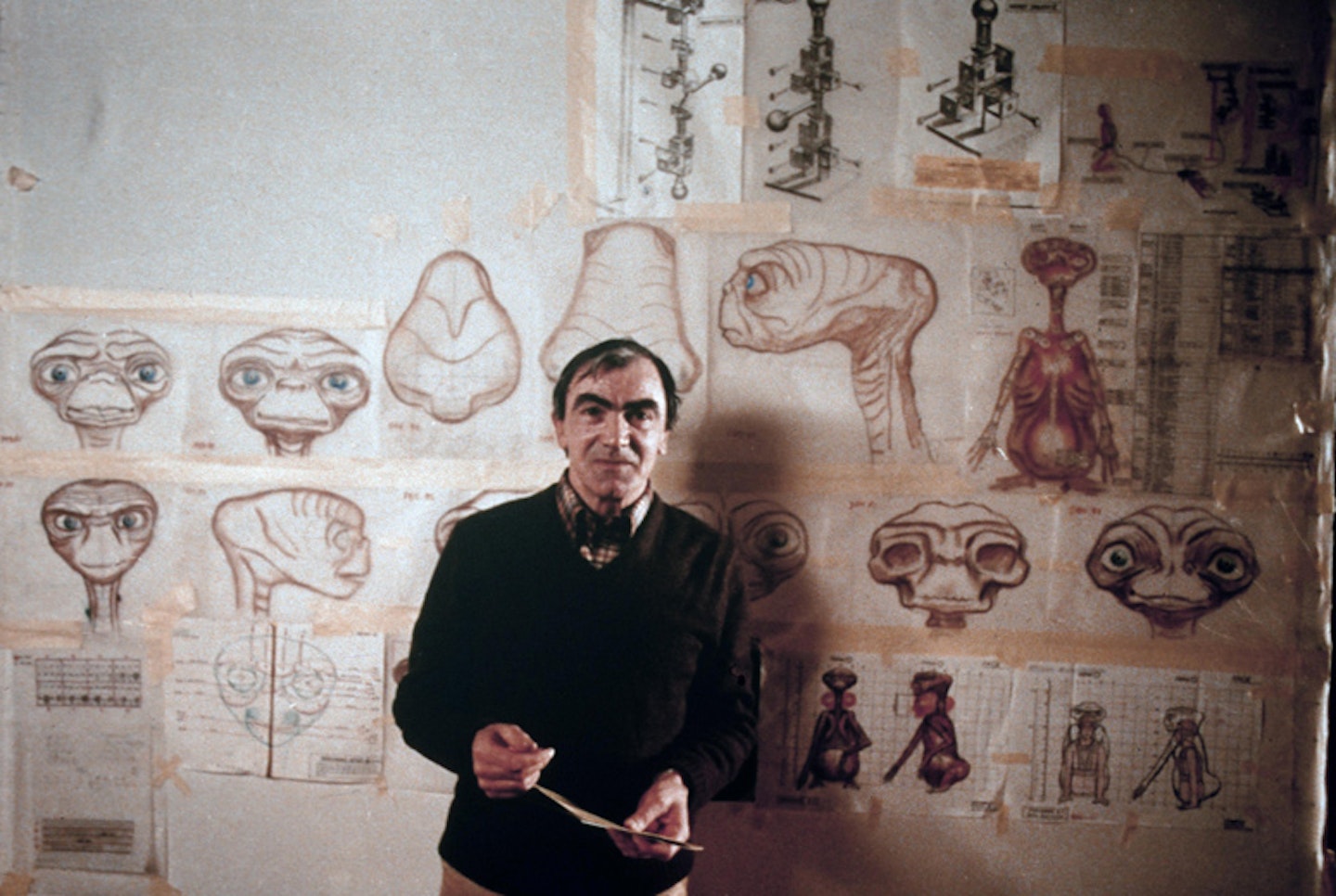

There was never a literal description of what the title star looked like in Melissa Mathison’s E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial screenplay, the final character being a fully-fledged collaboration between director and special effects technician. The pre-visualisation process took in the familiar — concept drawings by storyboard artist Ed Verreaux, ten inch tall prototypes sculpted in clay — and the not so familiar (Spielberg cutting and pasting a picture of the chin and nose of a five-day old baby onto the eyes and forehead of an Albert Einstein image to create a mixture of the innocent and the wizened). Yet Rambaldi’s input into the design process was crucial. The technician had a Himalayan cat whose eyes fed into the creature’s peepers. And most tellingly Rambaldi’s 1952 painting Donne del Delta (Women Of The Delta) portrayed one of its female characters with an elongated face and neck that proved influential on the character’s trademark telescopic neck. Donald Duck was also a key influence — on the character’s tush.

Once Spielberg gave him the get-go, Rambaldi manufactured three E.T. torsos (plus accessories), hovering up $1.5 million of the film’s $10 million budget. 1. A lightweight electro-mechanical version that was bolted to the soundstage floor, capable of thirty points of movement in the face, then thirty more in the body. 2. A more sophisticated auto electronic body that was brought out for close-ups that had eighty-six separate points of movements. 3 a cable-less suit capable custom designed for E.T.’s walking scenes. Rambaldi also fashioned four separate heads, one mechanical, one radio controlled (for the walking scenes) and two electronic. The hero head was the electronic one, capable of 35 different facial tics at the forehead, lips, eyes, eyebrows and tongue (getting E.T. to taste the potato salad was a bitch apparently — the two operators often mistiming so the poor alien would bite his own tongue).

It took twelve crew members to operate E.T. on set and the director noted it was an “average of three takes per human and 15 takes per E.T.”. “E.T. was treated just like a real actor,” Rambaldi recalled. “Eating and speaking were the most difficult actions had to perform. For example, it was hard to get him to mouth “E.T. phone home.” The mouth is the maximum portion of mobility in the body, because there are so many muscles concentrated in that area. Operating E.T, in those places was very tough.”

Still, compared to Bruce the shark, E.T. worked a dream. He was even capable of pulling off practical jokes like a cable-controlled Jeremy Beadle. At different times throughout the shoot, surprised crew members would catch him smoking a cigar, picking his nose, winking at hot women and waddling around a corner wearing a gauze mask to protect him from the foggy sets. He also pinched screenwriter Melissa Mathison’s derriere. Jokey japes aside, E.T. remains Rambaldi’s crowning achievement: a special effect at the centre of the movie that you never once think of as a special effect. As Spielberg himself put it: “Carlo was the biggest hero of the film.”