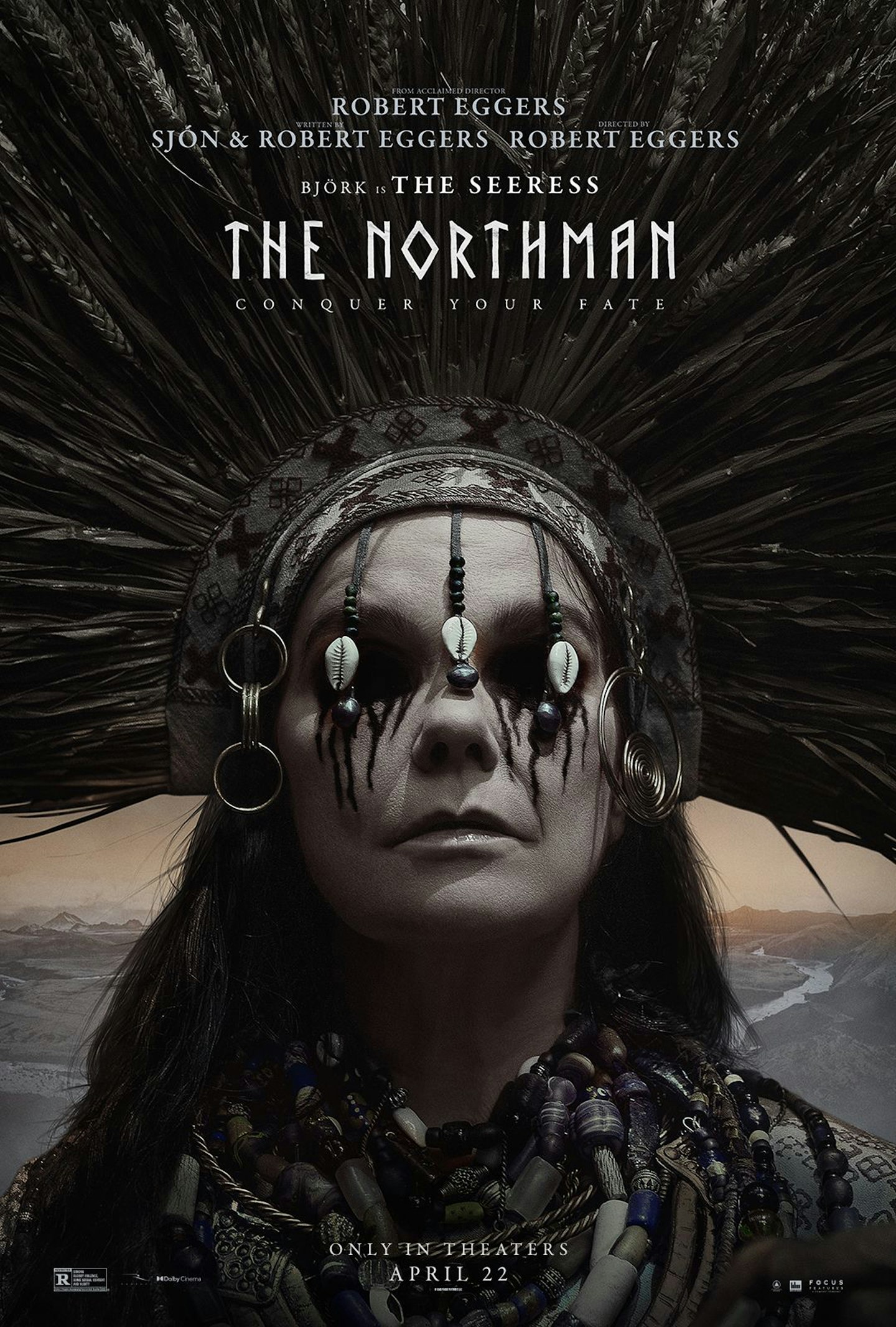

Björk gets her own character poster for The Northman. She’s only in it for two minutes, but she gets a poster. ‘BJÖRK IS THE SEERESS’, it announces. There are actors who are in practically all of The Northman who do not get their own poster. But they are not Björk. Of course she gets a poster.

The Seeress is given an arresting reveal. Up to this point in Robert Eggers’ Viking epic, Alexander Skarsgård’s Amleth has lost his way, having forgotten the oath he made as a child: he’s forgotten to avenge his slain father, to save his stolen mother, to kill his murderous uncle, instead opting for life as an animalistic berserker, bludgeoning people’s faces to bits. Here, though, in a burnt-out barn, he finds this blind mystic. She begins the scene with her back to us, turning around slowly, unsettlingly weaving wool, whispering, her face shrouded in shadow before, finally, the light hits her. And she lifts her head.

There are small shells where her eyes used to be, dangling over blackened pits. Below them, her cheeks are stained with… black tears? Black blood? She is wearing perhaps 20 necklaces, a ring on every finger and an imposing wheat-sheaf headdress which, according to Eggers, is a ninth-century wedding crown signifying that she’s married to the gods. You can believe it. Having appeared out of nowhere, she chides Amleth’s nihilistic brutishness, reminds him of his mission – and then vanishes. That’s your two minutes. Björk has been summoned, and has served her purpose. She has provided magnificence. Majestically.

This single scene is Björk’s first appearance in a traditional feature in 22 years. It was a role Eggers wrote specifically for her. “Björk as a seeress is a no-brainer,” he tells Empire. An Icelandic seeress, no less. Of course it was written for her; the scene looks like a Björk album cover that never was. How glorious it is to see her on film again. “Look,” says Eggers, “if you're doing something with Icelandic subject matter, many roads lead to Björk.”

When she came into her own as a solo artist after her band The Sugarcubes split in 1992, it was clear that making moving images was never an afterthought for Björk. She never took music videos for granted, each one an adventure. For her debut single, ‘Human Behaviour’, she employed director Michel Gondry, who would continue to work with her for two decades, creating fantastically absurdist gems for the likes of ‘Army Of Me’ (in which a gorilla dentist pulls an every-growing diamond out of Björk’s mouth) and ‘Bachelorette’ (in which she is consumed by a forest).

Björk thought that I would get along with Sjón, and she was correct. – Robert Eggers

She has always sought out singular artists, who have relished the chance to collaborate freely with her. The list boasts Spike Jonze, who made three videos with her (most notably ‘Triumph Of A Heart’, where she enjoys a drunken escapade after having an argument with her boyfriend, who is an actual cat), and Chris Cunningham, who directed her in the heart-crushing ‘All Is Full Of Love’ – a sensual, sexual, gorgeous masterwork in which two Björk robots make out with each other, white fluids gushing, sparks literally flying.

In all of her videos she goes for broke, pouring her heart out, baring her soul – just as she does in her music. There is not a shred of artificiality, of phoniness, of cynicism, in anything she does, and that unrestrained, unaffected purity comes through, cuts through, every time. So it wasn’t a revelation to see how devastating she was as the lead in Lars von Trier’s 2000 musical drama Dancer In The Dark, about a woman spiralling into merciless tragedy. Her performance – upsettingly raw, free from affectation – won her the Best Female Performance award at Cannes; the film won the Palme D’Or.

She later said that it was the most difficult thing she’d ever done, although disputed the fact that her decision to not act in a film again was because of it. She never wanted to act in the first place, she said, and simply made an exception for that (as she did again in 2005 for visual artist Matthew Barney – at the time her husband – in his project Drawing Restraint 9). On Facebook in 2017, she wrote that she was sexually harassed by Von Trier during the production of Dancer In The Dark (the director ‘declined’ her accusations). “Having no ambitions in the acting world,” she wrote, she walked away from the industry.

So the reports of her casting in The Northman were a surprise. Björk, though, was a key player in the film’s development. Eggers and his wife, clinical psychologist Alexandra Shaker, went to Iceland on holiday in 2016, and The Northman’s co-composer Robin Carolan – a musician friend of Eggers who had worked with Björk over the years – put them in touch. She invited them to her cabin, along with her novelist/poet friend Sjón and his wife, cooking salmon for them. Eggers didn’t realise Björk was matchmaking him and Sjón, who has written some of her lyrics over the years. “She thought that I would get along with him, and she was correct,” he explains. Eggers later tore through Sjón’s work, loved it, and when he began formulating The Northman, asked him to script it with him. Naturally, they ended up writing a role for Björk. It’s a coup, as much as Eggers might downplay it. “Well, I'm very fortunate but I think because of the familial atmosphere of all of these relationships, she felt it was something she'd want to be a part of,” he says. “And she's not in the movie very much at all – I also think that that made it easier for her to say yes!”

She was only on set for a day, but made the character her own. It was her idea that her eyes would be covered, and that she’d have a third eye; Eggers had discovered in his research of the period that certain proto-Ukrainian tribal women had cowrie (sea snails) shells in their headgear, so hung them over Björk’s eyes (and where her third would be).

Björk wrote on Instagram last week that she was “proud to be a part” of the film, mentioning that it felt good “to finally see one’s roots treated with imagination, intelligence and quality (omg i LOVED the mjötviður mær passages)” – she’s referring here to the Tree of Destiny sequences, borrowed from Scandinavian mythology, deployed to give Amleth visions of his family dangling from branches. Yet this is unlikely to herald a cinematic comeback. “I sort of did it as a favour for a friend,” she told the Los Angeles Times in January. “It’s not really my thing.” Like her previous two roles, it’s a mere exception – a blip.

But what a blip. As with all of her screen work, there is that purity in her performance – and, as always with her, boundaries blur. You never forget that you’re watching Björk. She is not Meryl Streep. She’s not a chameleon. She doesn’t need to be: she is only ever herself, and no director with any sense would ever try to change that. Throughout her Northman appearance there’s the hint of a smirk, as if she was giggling between takes, which she may well have been. A bit of a laugh before going back to the recording studio, to get on with her real work. Still: nobody does Björk better than Björk. She vibrates with honesty. “You want somebody who is just in the moment and completely alive, because that just makes you all the more alive,” said her co-star David Morse while promoting Dancer In The Dark. “And Björk is about as alive as people come.”

The Northman is out now in cinemas.