Candyman turned 30 years old this weekend. In almost any other circumstance, you’d call the film Bernard Rose’s horror masterpiece… but another name looms larger. Rose may have written and directed the film – but it was based on a short story called The Forbidden, published in 1985, and written by creative force Clive Barker.

Barker had started in experimental theatre in Liverpool in the 1970s, working with a rep company that included his school-friend Doug Bradley. Barker made short films during that period too, and then made a big splash with The Books Of Blood, published in six volumes between 1984 and 1985 (The Forbidden kicks off book five). He wrote screenplays adapting two of those stories – Rawhead Rex and Underworld, both directed by George Pavlou – and was so unhappy with the results that he decided to make Hellraiser himself, adapting his own novella, The Hellbound Heart. The million dollars he needed eventually came from Roger Corman’s New World production company. A strange sort of Faustian, Chekhovian, adult domestic drama about sexual obsession was the result – albeit with supernatural underpinnings, monsters and lots of blood. Hellraiser was very different to the Freddys and Jasons popular at the time. And yet, somehow, it became another of those extended horror sequel factories.

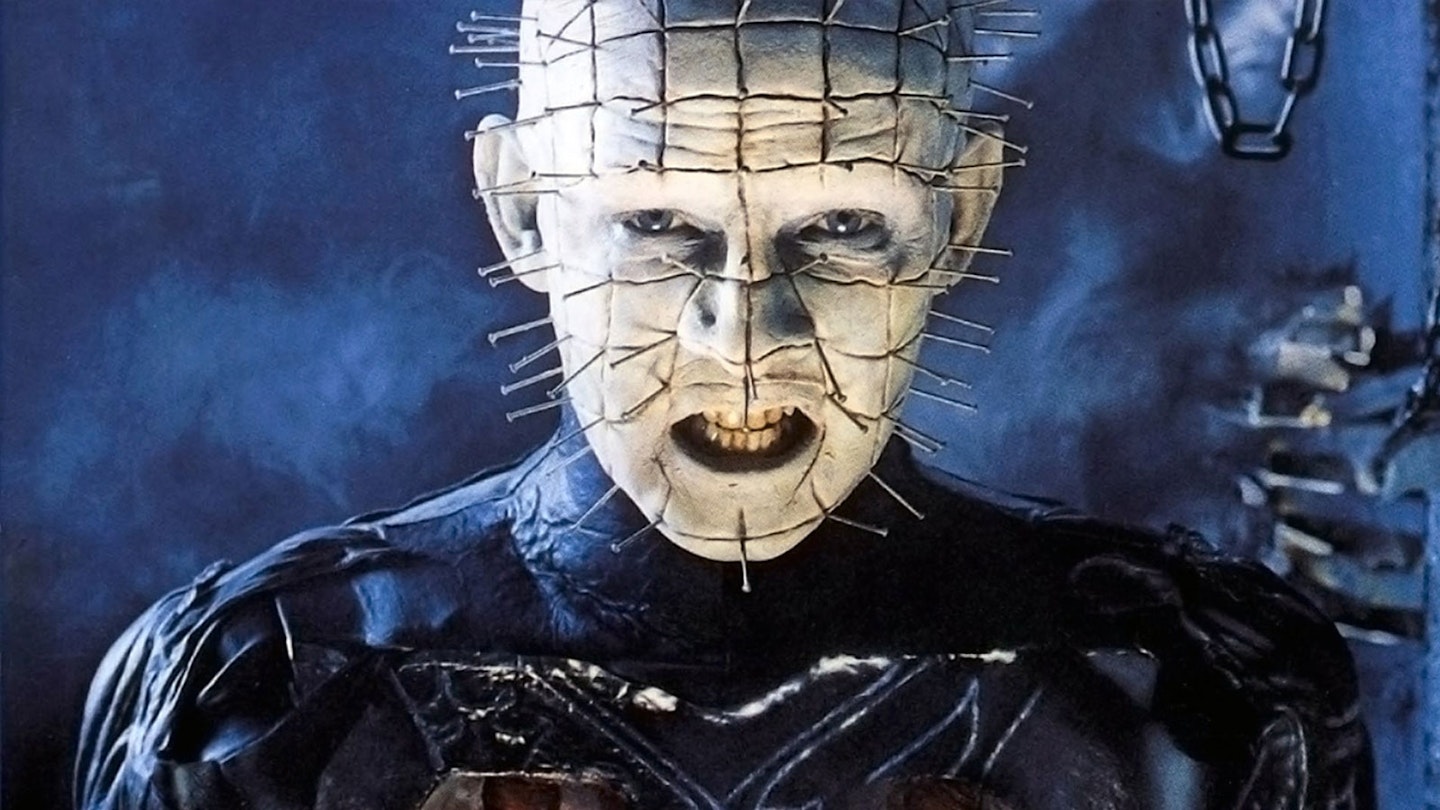

A small, contained film (set in and immediately around a single house in Cricklewood, although maybe it’s supposed to be America, since everyone’s weirdly dubbed) it nevertheless nodded towards a fascinating extended mythology. Bradley played a demon with pins in his head: a minor role on paper, but thanks to the actor’s wry gravitas and a startling make-up, one that audiences noticed. Hellraiser had a pair of fascinating villains in Julia (Clare Higgins) and Frank – a character who, thanks to prosthetic make-up FX and the body-swapping in the story, ends up being played by three actors; principally Oliver Smith, but also Andrew Robinson and Sean Chapman. But “Pinhead" ran away with the whole dubious "franchise".

“I think that’s something that Clive does,” Bradley mused to Empire, back in the September 2012 issue. “He’s great at dropping in these amazing characters that make you go, ‘Woah! Who are they?’, and then at the end of the film you’re still none the wiser. ‘We are Cenobites.’ Okay, and a Cenobite is…? ‘We are explorers in the further regions of experience.’ Yes, but who the fuck are you?!” Films of, shall we say, variable quality immediately followed to explore that question, written and directed by other people who seemed more interested in expanding Barker’s mythology than Barker was himself. He’d already moved on.

Barker’s fantasies were accessible from our own world, his crazy Narnias approached via the threads of a mysterious tapestry.

That Barker was able to get Hellraiser made speaks to the name he’d made for himself so quickly. Stephen King famously called Barker "the future of horror", although that endorsement quickly soured for an artist who didn’t want to be the future of horror at all; even The Books Of Blood themselves are often wittier than their reputation as purely grisly and terrifying. He followed Hellraiser with the botched Nightbreed in 1990, and the less-seen Lord Of Illusions in 1995, but has never directed since. Film seemed not to really work for him. His imagination was too huge for the frame. Budgets, technology and studios hindered what he was trying to achieve.

Rose’s Candyman arrived in 1992, the same year that Anthony Hickox’s Hellraiser III turned Pinhead into a full-on slasher, complete with maniacal cackle, kiss-off kill lines and nightclub bloodbath set piece. Candyman was altogether more classy, transposing Barker’s story from a derelict housing-estate in Liverpool to the destitute projects of Chicago’s Cabrini Green. In the process, it ran with Barker’s theme of class inequality but added a strong thread of racial politics, and an entire mythology – rooted in America’s 19th-century plantations – for its iconic, tragic “monster”. An instant classic and a critical and commercial hit, Rose had achieved what even Barker never had: a creatively uncompromised Clive Barker adaptation that was universally acclaimed.

Barker, meanwhile, was enjoying the creative and commercial heyday of his career in print. Alongside the short Books Of Blood came his first full-length novel, hardcore horror The Damnation Game. But he subsequently swerved into a sequence of huge books that were as much fantasy as horror. There were still monsters, and frightening things still happened, but, beginning with Weaveworld (1987) and continuing through The Great And Secret Show (1989), Imajica(1991), Everville (1994), Sacrament (1996) and the raging family saga Galilee (1998), there was also an unmatched sweep and breathtaking vision: a sense of wonder to balance the darkness; a torrent of subversive, gender-fluid erotica; a collection of extraordinary spheres of existence and the liminal spaces between them. As in works by authors like CS Lewis, L. Frank Baum or Stephen R. Donaldson, Barker’s fantasies were accessible from our own world, his crazy Narnias approached via the threads of a mysterious tapestry, the ocean of Quiddity or the chaos-space of the “In-Ovo”. A frequently recurring theme is the return and preservation of forgotten magic, or exotic creatures hidden among us. Imajica, the biggest of them all, is a road trip across four intricately drawn “Dominions” parallel to Earth (the fifth), by a human and his alien “Mystif” lover, to confront God.

It’s frankly an injustice that, 30 years and more later, we’re still only really talking about Hellraiser and Candyman, as if Barker was a two-hit wonder.

In between the big books there were smaller works like Cabal (1988, which became Nightbreed) and The Thief of Always (1989 – y’know, for kids!), and it’s startling to realise that Barker’s career as a major novelist only lasted a bit more than a decade, with Galilee marking the end of that era. There were novels afterwards, but it often felt that Barker’s heart wasn’t in them. Coldheart Canyon (2001) was a short story that got out of control and ended up at a rambling 700 pages. Tortured Souls (2001) was cobbled together from short pieces he wrote for a set of Todd McFarlane action figures. The Scarlet Gospels (2015) felt like Hellraiser tie-in fiction rather than a genuine Barker work. Notably, there’s also the Young Adult Abarat sequence (2002-2011… so far), where the story feels in service to the hundreds of lavish oil paintings that accompany the text. You get the feeling that these days, Barker would rather be at his easel than a desk.

Many of his big projects remain unfinished. In spite of his occasional protestations that they will happen eventually, that seems likely to remain the case. There probably won’t be a third Book Of The Art (to complete the promised trilogy begun with The Great and Secret Show and Everville) or a fourth Abarat. If you’ve been tapping your fingers since 2011 waiting for George RR Martin to write The Winds of Winter, imagine what it’s been like waiting 25 years for the second half of Galilee.

But Barker was never hugely enthused about revisiting even positive experiences. Perhaps he was burned out each time by the maniacal focus he gave to his projects. Imajica, he claimed, was written in 16 hour days, seven days a week, for 14 months. That doesn’t even sound possible, but if there’s even a shred of truth in it, it illustrates the sheer energy and obsession of the younger Barker. Fourteen months of laser focus, but then done, done and on to the next one. “His mind moves [so] rapidly," Bradley told Empire. "Even while he was writing Cabal and directing Nightbreed, he would have been planning another eight novels and films. Everything he’s ever done has always been the first in a cycle of 36. He was always like that.”

So, Barker’s was an imagination that other people ran with, in comics, spin-offs, video games and sequels; Rose’s Candyman unquestionably the high-water mark of the Clive Barker works that Clive Barker wasn’t actually involved with. Barker remains a presence, a name, a brand. The days of a thousand-page novel every two years are behind him, but he paints, he designs, he advises, he oversees, and pops up now and again to talk up a TV series or a film project – or occasionally to excoriate one. He said of Hellraiser: Revelations, “If they claim it’s from the mind of Clive Barker, it’s a lie. It’s not even from my butt-hole.”

As that exasperation perhaps testifies, it’s frankly an injustice that, 30 years and more later, we’re still only really talking about Hellraiser and Candyman, as if Barker was a two-hit wonder (with one of those hits largely by somebody else). Regardless of the lower profile he’s kept this century, the books he wrote during the 80s and 90s are still an incredible body of work. And yet, while it’s easy to source imports and second-hand copies thanks to the internet, not all of those books are even currently in print in the UK. He’s due a huge revival; the sort of attention and adulation that Neil Gaiman enjoys.

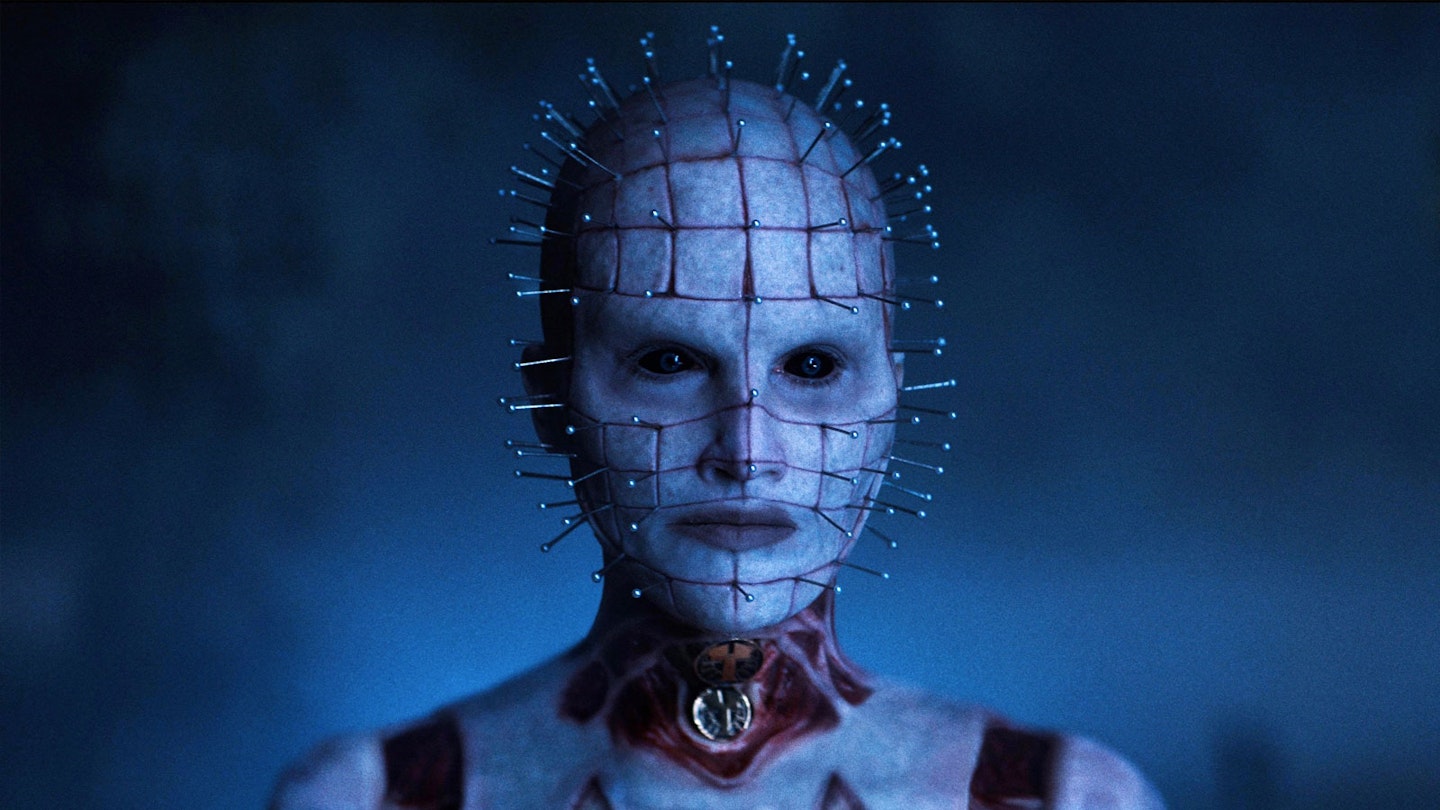

The titles he’s most associated with keep coming back. Nia DaCosta’s 2021 Candyman – co-written and produced by Jordan Peele – returned to Cabrini Green to deal with the politics of urban gentrification, as well as to unpick some aspects of Rose’s film that now play as racially problematic. David Bruckner’s recent Hellraiser ‘requel’ (to use Scream parlance), remixed elements of Hellraisers 1 and 2 through a story about the cast of Friends running around the set of Thirteen Ghosts. And those are all very well, but where’s the huge Netflix series of Weaveworld, or the mega-budget Prime adaptation of Imajica? When those novels were written, translating them to the screen would have been unachievable, but we’re now in an era where anything is possible through digital effects, and ten-hour-plus run-times are the norm. Let’s stop talking about Hellraiser and Candyman – great as they are_–_ and start championing the others. They have such sights to show you.

Want to get the most from Empire? Sign up for Empire Membership!

Get exclusive content, new member-only rewards, access to the latest issue of the magazine plus our back-issue archive, and much more.