It seems incredible, but 35 years ago the biggest box-office hit of the year featured no special effects or world-threatening stakes — just a mouthy police officer with cheap sneakers and a crappy car. Beating Ghostbusters, Gremlins and Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom at the US box office, Beverly Hills Cop became a surprise phenomenon, transforming Eddie Murphy from a big star to an enormous one, while inspiring all manner of cop-comedy rip-offs. Even more incredibly, Murphy wasn’t meant to be in it at all — he was cast only at the last moment, when Sylvester Stallone dropped out over script issues. In this excerpt from Empire writer Nick de Semlyen’s new book Wild And Crazy Guys: How The Comedy Mavericks Of The ’80s Changed Hollywood Forever, the unlikely success story of Beverly Hills Cop plays out.

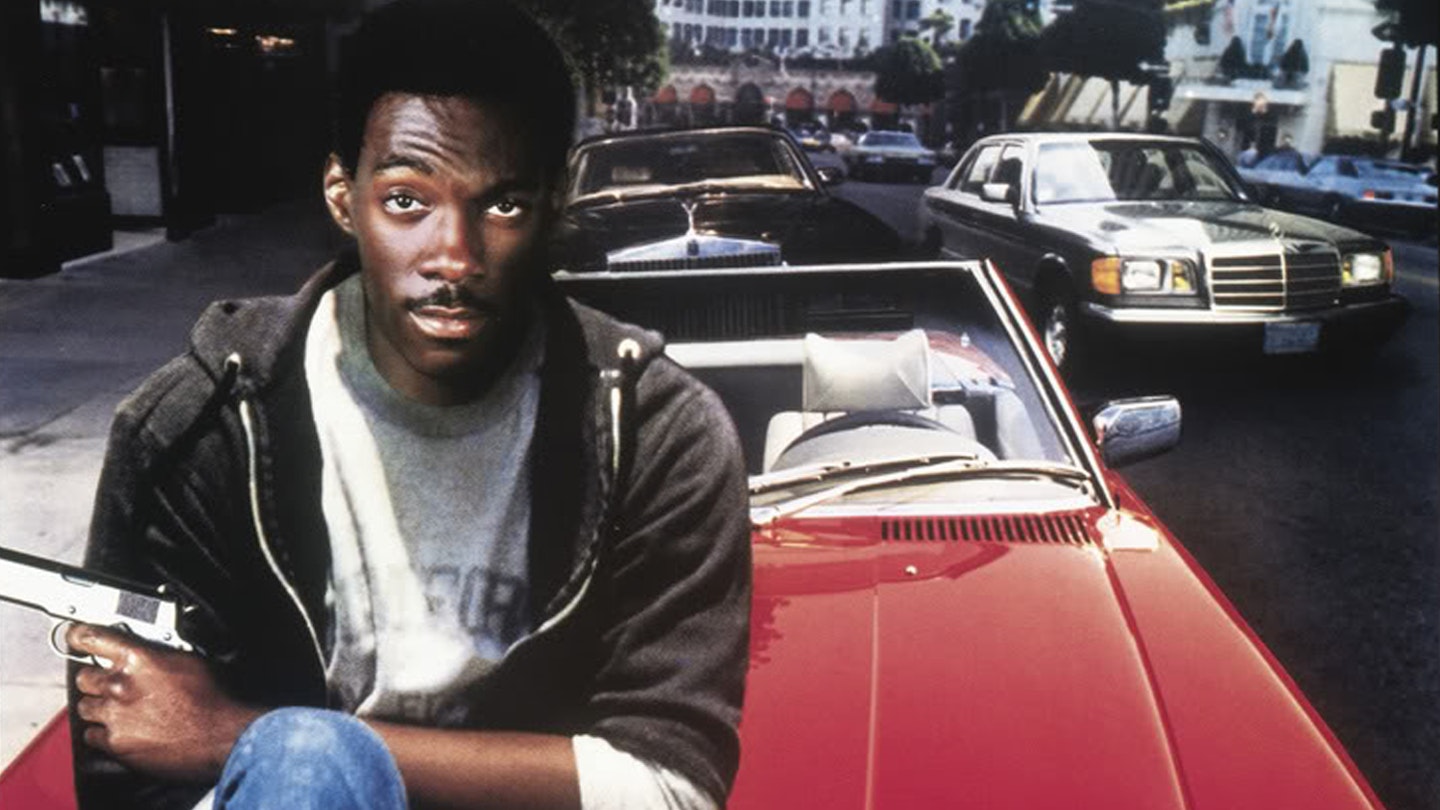

New sets and costumes were hurriedly assembled. New York–born director Martin Brest, himself skittish about directing a big action movie for the first time, got to work with Murphy and writer Dan Petrie, figuring out the whys and wherefores of the lead character, now at last called Axel Foley. Rather than the buffed-up, hardboiled guy he had become in recent drafts, they turned Axel into a scruffy wiseass, always flying by the seat of his pants. “We wanted Eddie to look like a kid,” said producer Don Simpson. Though a law-enforcement officer, Foley was to be an underdog perpetually snapping at the heels of his affluent enemies. And despite the fact the script had been written with white stars in mind, Murphy’s skin color only sharpened the him-against-them dynamic.

Murphy himself rejected the initial outfit that Brest, Simpson, and Jerry Bruckheimer picked out: it was, he told them, “too slick”. Instead, he opted for a pair of squeaky sneakers, a faded T-shirt marked MUMFORD PHYS. ED DEPT., and a shabby sweatshirt; the garments would match the character’s car, a blue Chevy Nova that was dented and covered in rust. “Everything he had was the cheapest, most lowdown possible,” said Brest. “The only thing he had going for himself was his wits.” Rather than keeping his gun in a holster, Axel would tuck it into his jeans — something Brest saw being done by real detective Gilbert Hill (whom he’d cast in the film as Foley’s foulmouthed superior, Inspector Todd) during a research recce to a Detroit cop shop.

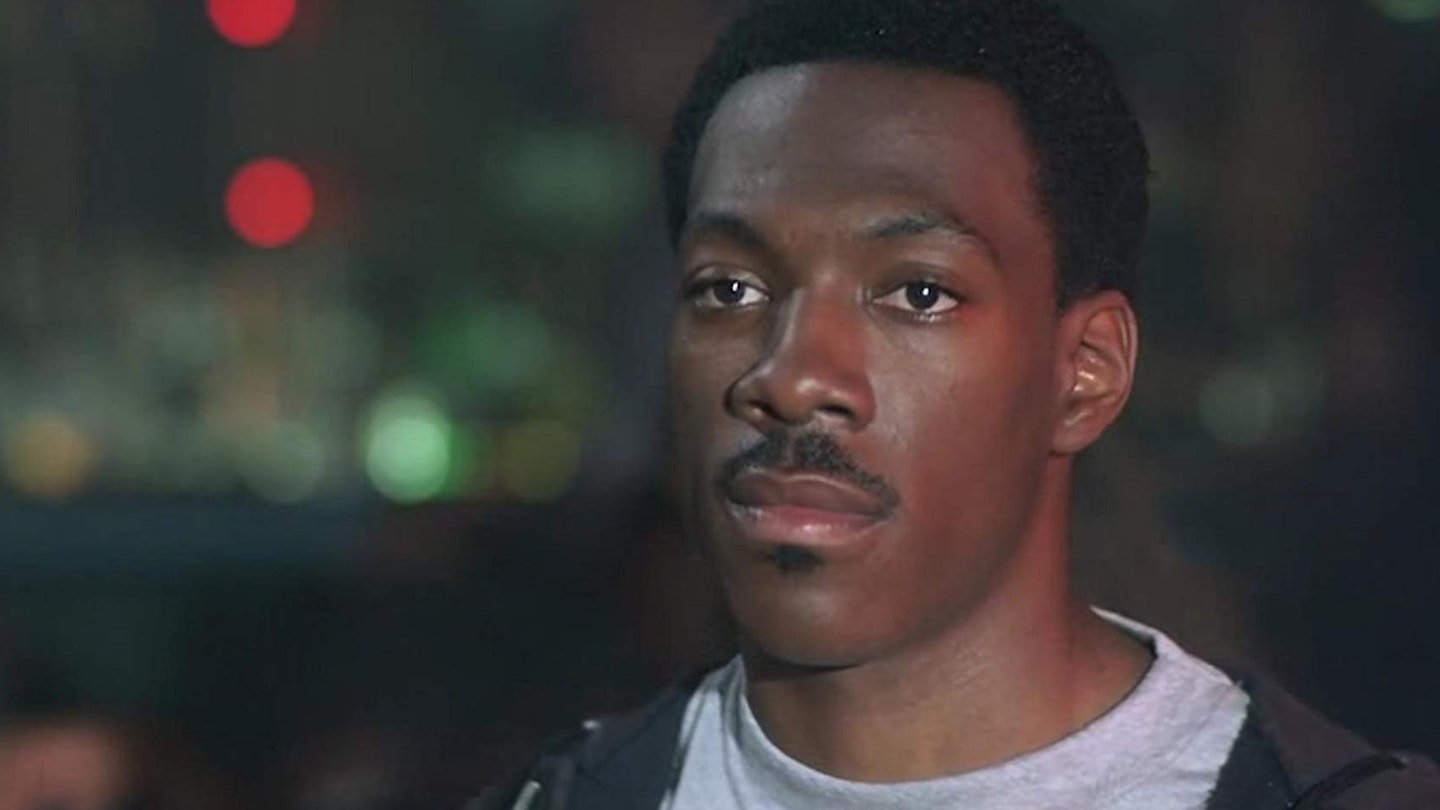

In spring 1983, production began, with final changes to the script completed that very morning. Murphy’s first scene was a tense exchange about hijacked cigarettes in the back of a truck, with dialogue inspired by a Harvey Keitel – Robert De Niro interaction in Mean Streets. Brest’s nerves quickly melted away as he realized Murphy was capable of fizzing up even the most generic of lines. “Every time, he came up with something that knocked me to the floor,” he said. “He’s a director’s dream. He magnifies every bit of work you do by a thousandfold.” The director kept a VHS tape of 48 Hrs. on hand on-set, so he could watch snippets of it for inspiration. But his star consistently delivered footage funnier than he’d imagined. One day Murphy, who never touched coffee, drank a strong cappuccino before improvising a monologue. The resulting caffeine-fueled riffs made Brest laugh so much he had to retreat to a nearby room and listen through headphones, covering himself with blankets to soundproof his giggles.

Foley and Murphy were a perfect fit: both were imbued with super-human chutzpah, waltzing through Hollywood, listening to no-one, making jokes out of everyone. “Of all the characters I’ve played, Axel is the most like me,” the star acknowledged. “He walks like me, he talks like me, he reacts to situations the same way that I do.” Backed up by the Laurel and Hardy double-act of John Ashton and Judge Reinhold, as well-meaning but dozy cops Taggart and Rosewood, he made the most out of every gag he got. Not least a memorable bit of business with a banana (replacing the original script’s potato), which Foley stuffs up the tailpipe of a pursuing villain’s car. Like Trading Places, Beverly Hills Cop was ultimately a movie about class, the blue-collar hero cutting a path through a procession of straight men, from a snooty maître d’ to dead-eyed, art-gallery-dwelling villain Victor Maitland (Steven Berkoff).

When rough footage was screened to a test audience, it elicited such rapturous reactions that Murphy, sitting at the back with Brest, exclaimed, “It’s hot!”

What was new for Murphy was the action. On 48 Hrs., he’d been content to wave a gun around and channel Bruce Lee, but here he got to do some bona de stunts, albeit not the steroidal ones Stallone had had in mind. The movie’s opening sequence, in which Foley battles henchmen in the back of a speeding truck, was shot in downtown L.A., with the vehicles running through red lights as a police escort led the way. It was the most dangerous day of shooting Brest had ever been involved in; he sat in a pursuing car, gripping a megaphone with a white-knuckled hand, bellowing at Murphy before each turn so he could hold on tighter. The climactic shootout, meanwhile, was filmed at a stately mansion once owned by gangster Bugsy Siegel.

Murphy arrived each morning in a stretch limousine, filled with friends and hangers-on. It was his first time shooting a movie in California and he partied nonstop, paying frequent visits to a discotheque called Carlos ’n Charlie’s and on one occasion getting into a fight there that ended up as a wrestling match on the dancefloor. But despite the late nights, his co-stars were impressed by his focus. Berkoff marvelled, “He is the perfect Brechtian. He stands outside his character and works it like a puppeteer… When you do a scene with Murphy, he really listens to you, like he’s studying you… as if he was absorbing you, sucking your molecules.” Berkoff was even more impressed when the comedian caught him studying the stretch limo one afternoon, then let him have it for his journey back to his hotel.

Long before the picture wrapped, it had become evident that Beverly Hills Cop would not be another Best Defense. When rough footage was screened to a test audience, it elicited such rapturous reactions that Murphy, sitting at the back with Brest, exclaimed, “It’s hot!” And that was before the ludicrously catchy theme tune, a synth number recorded by Harold Faltermeyer on a Roland JX-3P and Yamaha DX-7, had even been added. So confident were Paramount that they decided to open it on Wednesday, 5 December, rather than the planned Friday, December 7, and wider than usual. They also front-loaded their advertising campaign, splashing out $5 million pre-release rather than the standard $3 million.

The result was delirium for the studio and calamity for their rivals. “This is the year the Grinch stole Christmas,” lamented 20th Century Fox’s president of distribution, Tom Sherak, as he watched Beverly Hills Cop stick bananas up the tailpipes of its expensive competitors, the likes of the Clint Eastwood–Burt Reynolds team-up City Heat, the sci-fi epic Dune, and the well-reviewed Starman. A staggering one in three ticket buyers was opting to see the comedy; half of those polled coming out of it said they wanted to see it again. It became the first Eddie Murphy film to do gangbusters not just in cities, but in America’s heartland and across the globe. Having cost just $15 million, its receipts soared up and up and up, eventually surpassing $316 million worldwide, about $20 million more than Ghostbusters had made.

Unlike that film, it had zero in the way of visual effects. Unless you counted Eddie Murphy’s grin, a huge, infectious thing the Washington Post described as a “Studebaker-grille smile.” It helped make Beverly Hills Cop that rarest of things: a fun movie about a cop. “In most films the cop wakes up alone in a shitty apartment, has a cup of horrible coffee, then gets served divorce papers by his wife,” says Petrie. “But in this one you can see the enjoyment pouring out of Eddie all the time. Even though he’s at odds with all the people around him, he charms them all.”

That charm wafted off the screen like a love spell, intoxicating all who took a sniff. “Everybody seems to love it. Old folks, young folks, men, women. I imagine that even cops in Beverly Hills love it,” wrote newspaper columnist DL Stewart. “When it first came out, friends used to call me in the middle of the night to urge me to go and see it. Strangers stopped me on the street to tell me how great it is.”

Fans kept going back and back and back. “Me and my friend Fred Barton, we saw Beverly Hills Cop three times the first day it came out,” says Chris Rock, who would make his movie debut in the sequel. “We just wouldn’t leave. Doing a movie twice was normal. We did 48 Hrs. twice, we did Trading Places twice, but this one we did three times. It was like, ‘Whoa!’”

Faltermeyer’s theme became a number-three hit on the Billboard chart. Even Axel Foley’s shabby sweatshirt became must-buy merchandise. Samuel C. Mumford High School, picked as the source of Foley’s signature garment because producer Bruckheimer was a graduate, got a flood of phone calls, asking where the sweatshirt could be bought. The school eventually commissioned Kansas company Artex Manufacturing to make up 24,000, sold for $10 a pop.

The promotional tour was intense; for the first time Murphy was the sole front man, deployed not just to Saturday Night Live but all over the country. The day after the movie opened, he drove alone to the shopping mall in his hometown of Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, utterly exhausted. Instead of exiting the car, an unremarkable older model instead of the Porsche or the Jaguar, he turned around so his face was pressed against the seat, and took a nap. He was woken by the sound of a group of people walking past the vehicle, yelling, “Bum!” and “Get a job!” He stayed there facedown, just listening.

Two days later, he returned to the same mall. This time, people in the parking lot, immediately recognising him, greeted him with high-fives and shouts of “Hey, brother!”

“Both days,” Murphy reflected of the dissonant experiences, “were really cold for me.”

Wild And Crazy Guys is out on 6 June as hardback, e-book and audiobook.