We’re at the midway mark now in Empire’s countdown of this century’s greatest movies – a list of the contemporary classics that have defined the past two decades of cinema. It’s full of favourites – compiled in a combination of lists submitted by Empire critics and those picked by readers, resulting in a definitive rundown of the 100 greatest 21st Century movies.

You can already read numbers 100 – 91, 90 – 81, 80 – 71, and 70 – 61 on the list – and below you’ll find the next ten movies to have found their way into the top 100. Stay tuned to Empire Online as we unveil more of the full list in the coming days, and look out for more information coming soon about Empire’s upcoming 100 Greatest Movies Of The Century magazine issue and podcast special.

60. Carol (2015)

Phyllis Nagy’s screenplay for Carol, based on Patricia Highsmith’s pseudo-autobiographical 1952 novel The Price Of Salt, was in development hell for 20 years. But in the hands of Todd Haynes, and with Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara as co-leads, it was more than worth the wait. Far more romantic than Highsmith’s murderous Ripley novels, it’s no less subversive for its depiction of a lesbian relationship under siege by various representatives of wider "society". And it’s therefore a natural fit for Haynes, whose whole canon has been about exploring non-conformity. Meticulously designed and photographed, its noirish melodrama is a perfect showcase for Blanchett at her most theatrical, the performative Carol all cigarettes and hair-tossing, recalling Blanchett’s knockout turn as Katharine Hepburn in Scorsese’s The Aviator. It’s a note-perfect match of actress and role.

59. Django Unchained (2012)

Having rewritten World War II in Inglourious Basterds, Quentin Tarantino delved further back for his next piece of revisionist history – creating a blaxploitation-inspired hero to fight back against American slavery. With liberal use of the n-word and disturbingly graphic whippings and ‘mandingo’ fights, Django arguably revels in its unflinching depiction of the Antebellum South to an uncomfortable degree. But it also doesn’t sanitise the cruelty – and when Django starts hunting bounties, taking down slave owners and racists with a broad grin, the vengeful violence becomes more appropriately gleeful. Jamie Foxx excels in the titular role (Will Smith famously turned it down, a missed opportunity to rank alongside his rejection of The Matrix), but it’s Samuel L Jackson that registers best – his institutionalised slave Stephen, fiercely loyal to Leonardo DiCaprio’s unrelentingly nasty plantation owner Calvin Candie, emerges as one of Tarantino’s most complex creations. Perhaps more enjoyable than a film about slavery should be, but the Candyland climax is glorious.

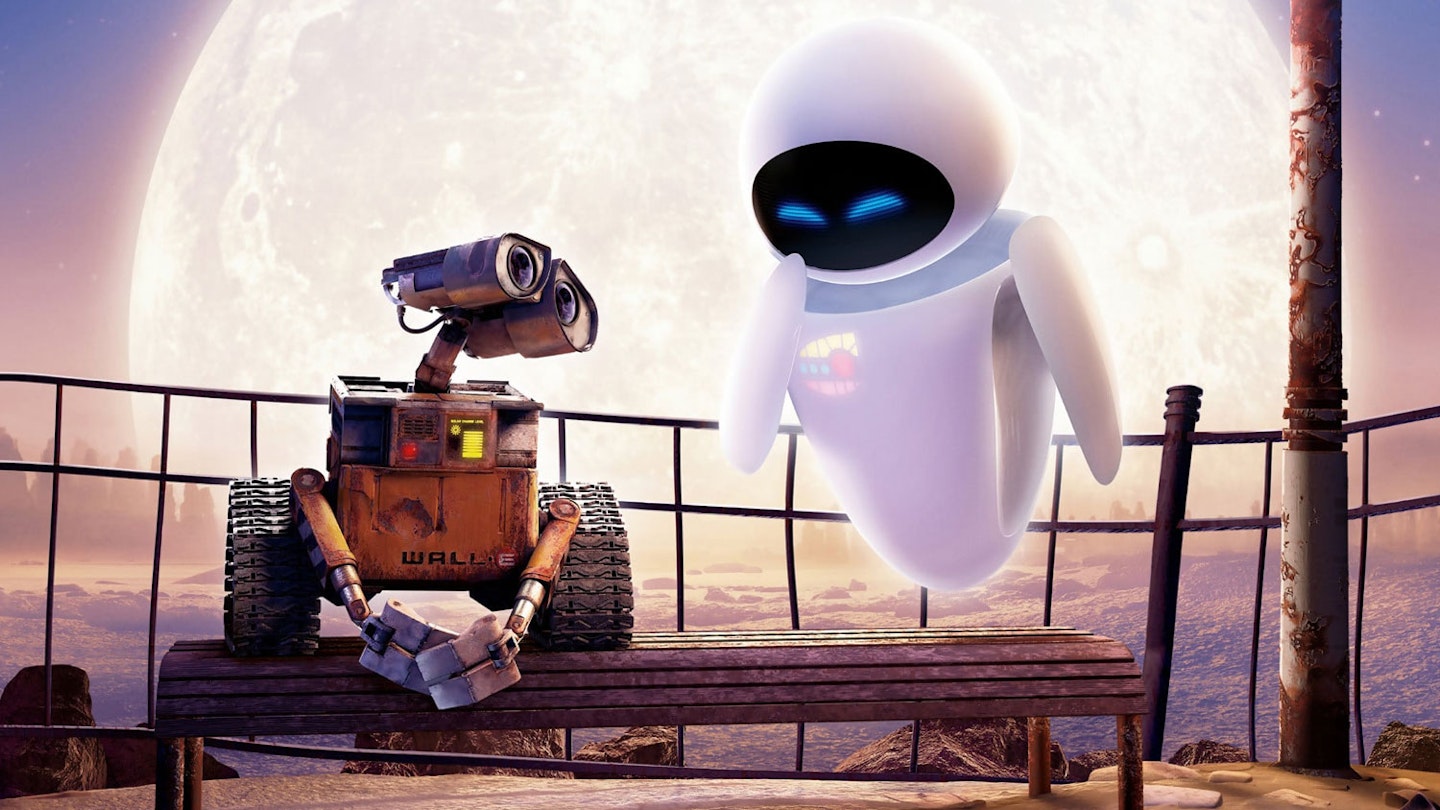

58. Wall-E (2008)

The opening act of Wall-E might be Pixar’s greatest feat – a stunning piece of near-wordless post-apocalyptic science-fiction, setting playful Chaplin-esque slapstick against a spectacularly bleak future Earth. As the titular trash-compacting android trundles through the mountains of waste left behind by a long-gone human race, he delights in the oddities he discovers (a Rubik’s cube! A bra! A fire extinguisher!), while we despair at the logical endpoint to our wasteful consumerism. A ridiculously charming romance with Apple-esque advanced robot Eve balances the bleakness – the pair’s interstellar dance is astonishing in its beauty). If its adventure-quest second half feels a little safe following that brave opening, the mission to save a single viable piece of plant life taps directly into fears around global warming a full decade before it became the leading issue of the 21st Century.

57. Drive (2011)

The same year that brought Fast Five also delivered its tonal opposite – an arthouse car movie that’s an exercise in pure style. Easily Nicolas Winding Refn’s most accessible work, there’s a clarity of vision that coheres through everything about Drive: the music, the stylised costumes (who hasn’t dreamed about pulling off that silver scorpion-patch bomber jacket?), and the intentionally-muted performances. Ryan Gosling’s stoic gearhead is an intentional void at its centre, his emotions awakening when Carey Mulligan’s struggling mum Irene brings much-needed humanity to his world (and the film itself). The perfectly-picked soundtrack– from Kavinsky’s ‘Nightfall’ to College’s ‘A Real Hero’ – feel integral to its success and enduring appeal, so much so that an experiment from the BBC to re-score the film to alternative songs couldn’t help but feel redundant. Ice cold and neon-lit, Drive plays it utterly cool – and even years later, it remains utterly cool.

56. Before Sunset (2004)

Nine years after that night in Vienna, Celine and Jesse reconnect in Paris; Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke slipping effortlessly back into their respective romantic personae in an unforced, entirely organic sequel. This time it’s more complicated: the pair come with a decade more baggage, and Celine isn’t entirely impressed by the post-slacker autobiographical novel Jesse has written based on their original encounter. As before, the narrative takes place almost in real time: in this case in the couple of hours before Jesse has to catch a plane. And as before, a generation of viewers is willing them not to go their separate ways at the end. As indelibly seductive images go, Delpy dancing in her apartment to Nina Simone is up there with Anita Ekberg in the Trevi Fountain. The subsequent Before Midnight, another nine years on, confirms that Jesse thought so too.

55. Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014)

Through his first two MCU outings – Captain America: The First Avenger and Avengers Assemble – Steve Rogers was faced with clear-cut enemies. But there are no overt Nazis or marauding aliens in The Winter Soldier, a film which forces Cap to face the complexity of 21st Century America. Revealing the ‘good’ of SHIELD and evil of HYDRA to be intertwined, the film is effectively a blockbuster political thriller that challenges its central hero to stay pure and true when surrounded by corruption and concealed villainy. As a superhero film, it’s thrillingly grounded – incoming directors Anthony and Joe Russo (then best known for helming sitcom episodes) delivering hard-hitting hand-to-hand combat fight scenes that pushed the limits of 12A. From the close-quarters lift scrap to the Nick Fury car chase, it delivers in a completely different way to the more fantastical end of the MCU spectrum. Plus, its warnings around dormant forces of fascism came years before the rise of the alt-right in the late 2010s.

54. Brokeback Mountain (2005)

A film about gay cowboys had the potential for parody, but Brokeback Mountain sidestepped that to earn massive festival buzz and an ultimate awards frenzy – testament to its deep sincerity, the empathy of its writing (by Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana, from Annie Proulx’s short story) and direction (by Ang Lee, rehabilitating himself after the ordeal of Hulk), and the committed, heartfelt central performances of Jake Gyllenhaal and Heath Ledger. Lee says he just pointed the camera and let his actors work. That’s giving himself too little credit, but it’s true that there are no stylistic tics, no dramatic posturing or grand gestures, nothing lurid or gratuitous. It’s purely and simply a film about closely observed characters and breathtaking landscape, and it never feels less than truly, emotionally authentic.

53. The Lord Of The Rings: The Two Towers (2002)

Being the middle part isn’t easy. And yet, without a definitive beginning or ending, The Two Towers excels in every way the central part of The Lord Of The Rings trilogy needed to – broadening Middle-earth, and challenging the fractured Fellowship in new ways as the sheer weight of their monumental task becomes apparent. If the Frodo and Sam story sometimes gets bogged down in the marshes, the thread that sends Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli to Rohan is utterly compelling. On a technical level, it saw the dawn of motion capture with Andy Serkis’ iconic Gollum – a visual effect that still largely holds up today, especially when seen on original 35mm prints, carried through on the weight of Serkis’ captivating performance. And then there’s Helm’s Deep – the astonishing climactic battle sequence that stands as the trilogy’s best. It redefined what big-screen fantasy clashes could be, masterfully blending miniatures and epic sets for a tangibly rain-lashed siege. Try to imagine Game Of Thrones existing without it.

52. Inglourious Basterds (2009)

After Grindhouse disappointed financially, Quentin Tarantino hit back with a World War II epic that ends on a ballsy brag: “I think this just might be my masterpiece.” Whether or not that’s the case, his Inglourious Basterds (pinching the name of largely-unrelated 1978 Italian war movie The Inglorious Bastards) increasingly grows in stature – a film of distinct extended chapters, many of which don’t even feature its titular Nazi-hunting Jewish soldiers. Whether it’s focusing on Christoph Waltz’s mesmeric, ruthless Nazi colonel Hans Landa (a contender for the all-time-great QT character) or devoting half an hour to a wrenchingly tense barroom game behind enemy lines, Basterds is 150 minutes of pure entertainment – a middle-finger to the history books that allows French cinema nerds and Southern-twanging American heroes to win the war. It’s Tarantino at his most playful, endlessly quotable (“That’s a bingo!”), with brilliant writing even by his standards, and great performances to boot (Waltz, Brad Pitt and Mélanie Laurent, to name but a few). Hell, it could be his masterpiece after all.

51. Paddington 2 (2017)

“If we’re kind and polite, the world will be right.” Paddington 2’s central adage couldn’t feel more necessary right now, perfectly encapsulating the optimism, pure-heartedness and beautiful simplicity that make Paul King’s sequel such an unalloyed pleasure. Doubling down on everything that made the first film so delightful, Paddington 2 is a film whose cuddly exterior perhaps disguises its astonishing craft: the Wes Anderson-esque pastel-perfect palette, meticulous toybox aesthetic, and carefully calibrated slapstick. Boasting excellent turns from Sally Hawkins, Brendan Gleeson, and particularly Hugh Grant – at his very best playing villainous luvvie Phoenix Buchanan, earning himself a BAFTA nomination in the process – it’s an embarrassment of riches on every front, made all the more endearing for its utter lack of cynicism. Like the first film, it gives a hard stare to regressive attitudes around race and immigration, and revels in simple acts of love and kindness. And marmalade sandwiches.