Like all great masterpieces, the years haven't diminished Apocalypse Now - it's every bit as mesmerising, trippy and poetic as it was when it stunned audiences back in 1979. Thanks to a new digital restoration presided over by Francis Ford Coppola, the Vietnam War opus is back on the big screen. Its epic centrepiece is a 12-minute chopper assault that, with due apologies to Saving Private Ryan, Spartacus et al, could just be the single greatest combat scene in cinema, The attack was meticulously storyboarded by Coppola and production designer Dean Tavoularis. Empire asked Doug Claybourne, helicopter wrangler on the scene, to talk through the shoot.

Easter, 1976. Doug Claybourne, who’d worked on Francis Ford Coppola’s City magazine, found himself sitting in the director’s house in Manila watching early footage of the aerial maelstrom the director was putting together on Apocalypse Now. The scene, which looked for all the world like the climax of a movie, would, unbelievably, appear just shy of the midway point. “That was the first thing I saw when I arrived in The Philippines” he remembers, “I was really blown away. I just thought, ‘Wow!’”

Claybourne was 29 at the time and a Vietnam veteran himself. A couple of days later he'd lent his services to the movie and found himself whisked off as a unpaid production assistant. The destination? The fictional Vietnamese village of Vinh Dinh, better known as Baler - a few hundred miles north east of Manila on the Philippine island of Luzon. "The middle of nowhere," as Claybourne describes it.

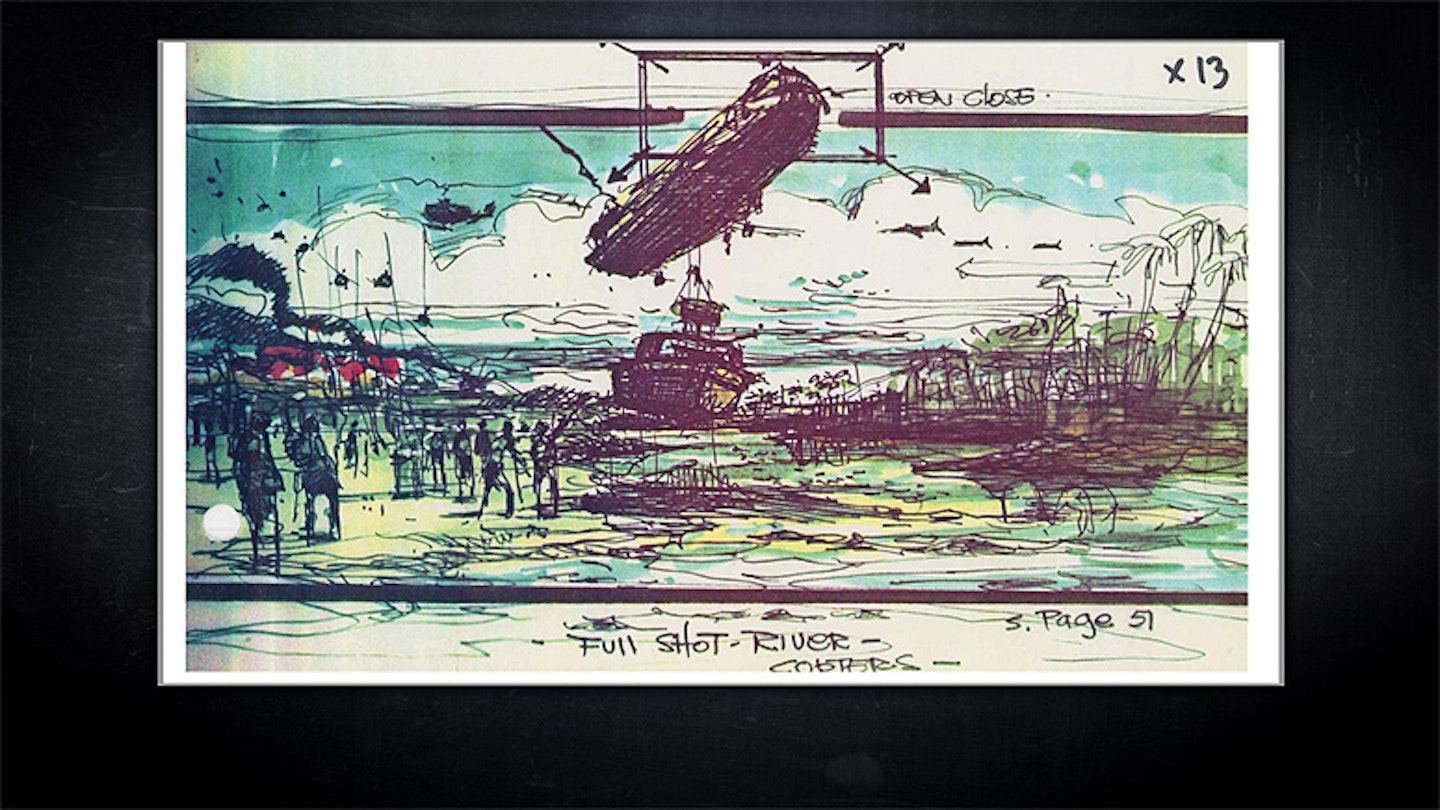

A DC3 and two jeep rides later, Claybourne arrived to find a shoot already bogged down. Two Italian assistant directors had been sacked, leaving the production manager filling in as an ad hoc AD and Coppola brandishing the bullhorn on the beach trying to engineer the film's most ambitious scene - the aerial attack - with as much calmness as he could muster. “There was a lot of chaos,” recalls Claybourne. The US military under Secretary of Defense - and proto bad-guy - Donald Rumsfeld had already refused to lend a single helicopter or pilot until substantial changes were made to the script, changes Coppola wouldn't contemplate. Instead the director and producer Fred Roos went cap in hand to Ferdinand Marcos. The Philippine president agreed to lend the Hueys needed for the scene, although he came up short on Cobra gunships and a Chinook to haul Willard's boat.

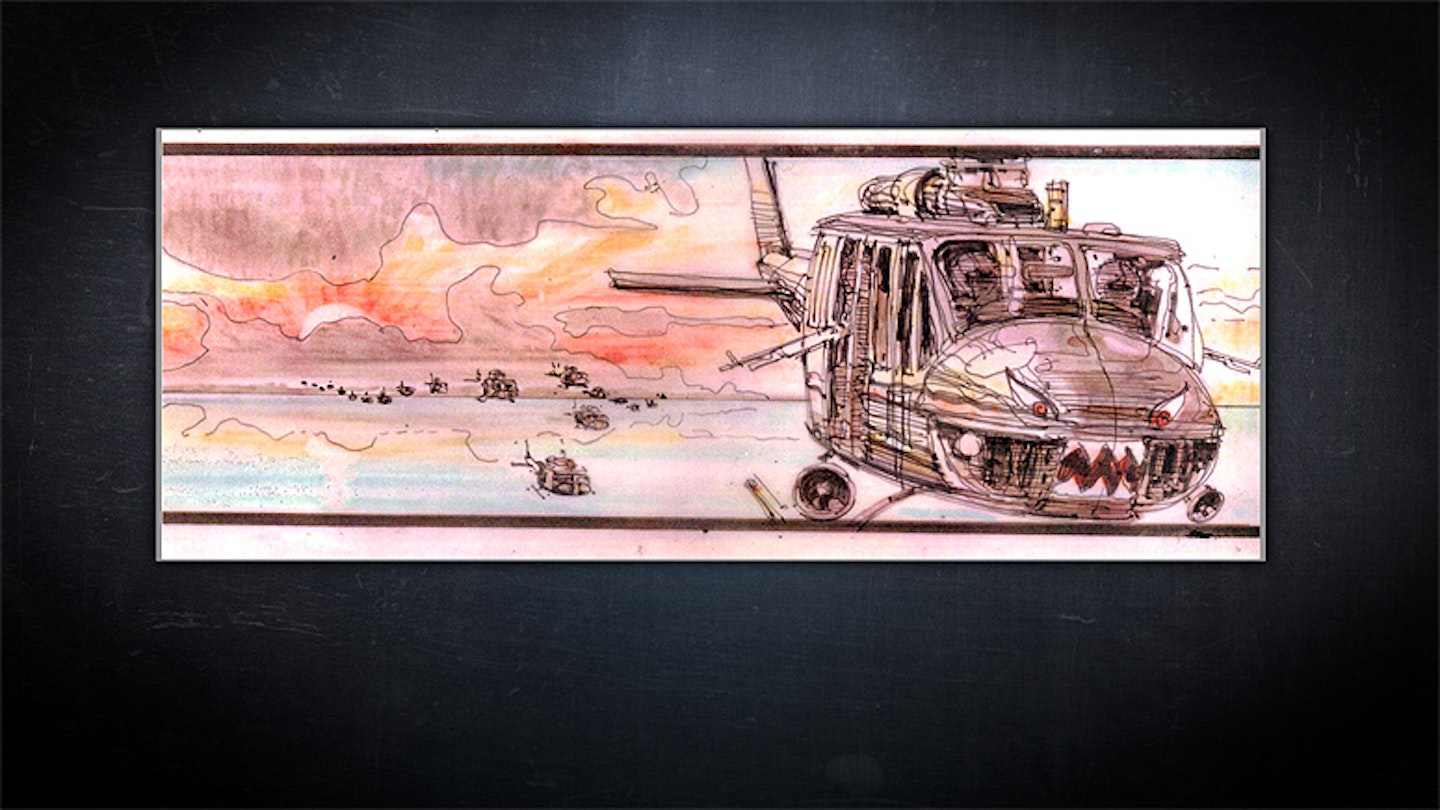

As per Dispatches author and Apocalypse Now narrator Michael Herr's war reportage above, choppers were both the Air Cavalry’s beast of burden and its bird of prey in Vietnam. Apocalypse Now's centrepiece air attack on the Viet Cong-held village would flaunt both: Hueys and Hughes 500s would swoop down on the village bristling with ordinance, while another chopper hauled in Willard’s PBR [Patrol Boat, River]. Well, that was the plan anyway.

The problem was that Marcos was involved in a war of his own. The quelling of a revolt in the south of the country took precedence over Coppola’s needs. “We could never tell exactly how many Philippine Army helicopters were going to come,” remembers Claybourne. “They’d say there were going to send five and they’d send three. Then at the end of the day, they’d get a call on the radio and they’d have to leave because they’d need helicopters for the insurrection.” Usually the US army markings would be hastily painted over with Philippine Army livery before flying into combat, but as Claybourne remembers, the guerrillas would sometimes find themselves under attack from Hueys with the US star still painted on the side. “They’d take off with our markings on them,” he recalls. “That was a challenge.”

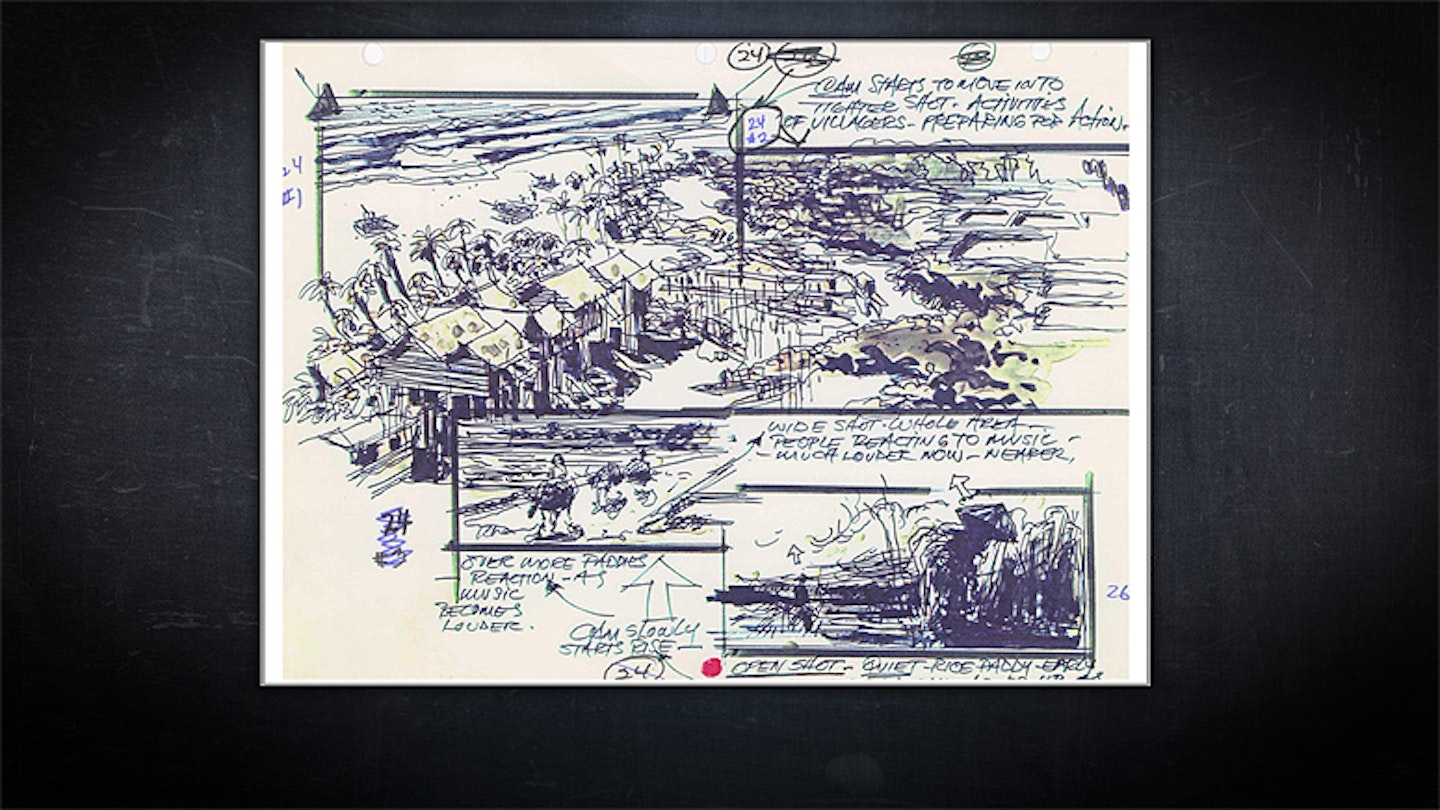

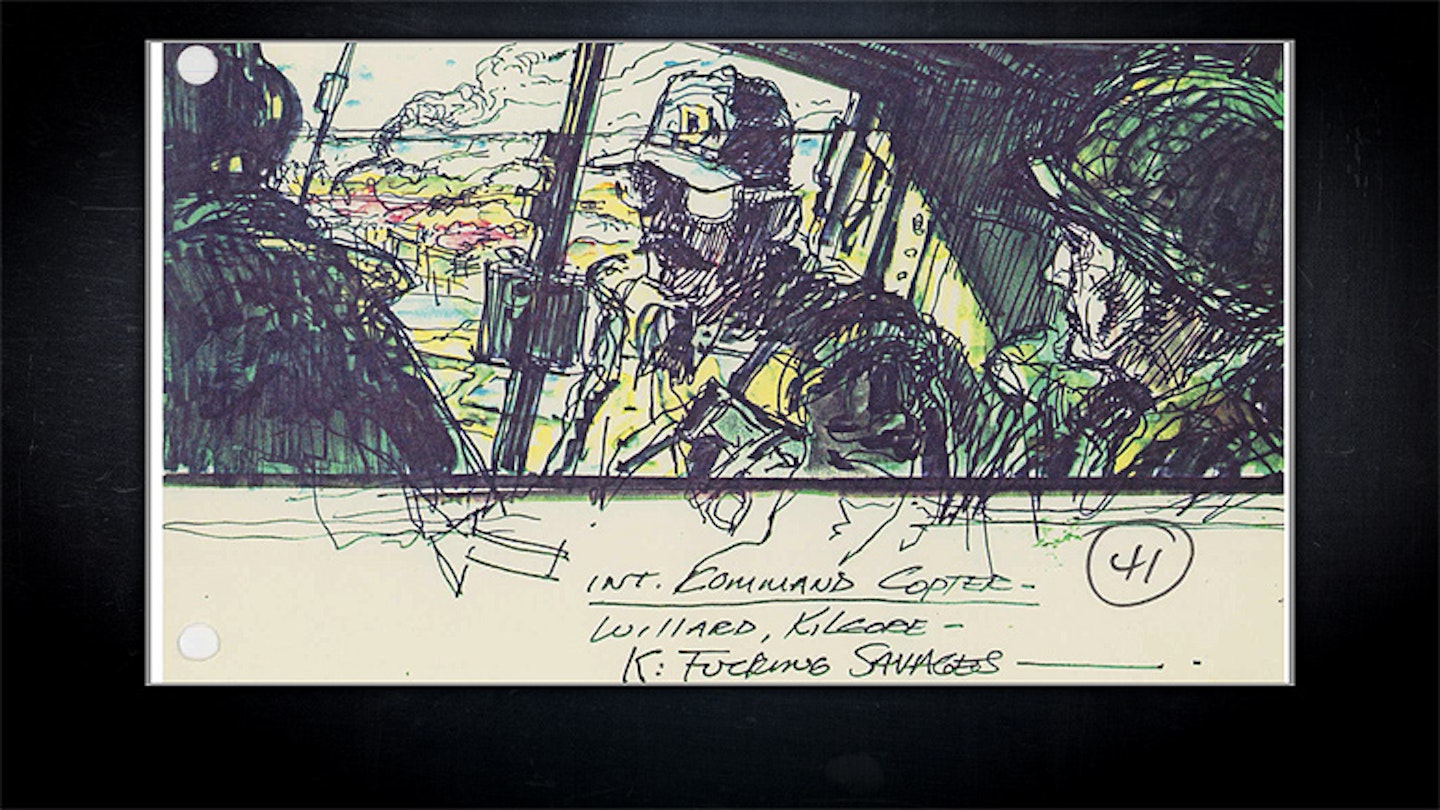

If Apocalypse Now was an "Los Angeles dream of war" as Coppola suggests, this scene went to bed with a head full of Westerns. As Willard wryly observes in voiceover: "The First of the Ninth was an old cavalry division that traded in their horses for helicopters and went tear-assing around 'Nam looking for the shit." All the cavalry props used in the scene were based on the AirCav in Vietnam, right down to Kilgore's Custer-like neckerchief, bugle and the blaring Wagner. "Somebody asked me recently if I’d experienced anything like the Wagner during the war," says Claybourne, "and I heard that it did definitely happen. Dean (Tavoularis) and the props department did a lot of research and watched a lot of Vietnam films. They did their homework."

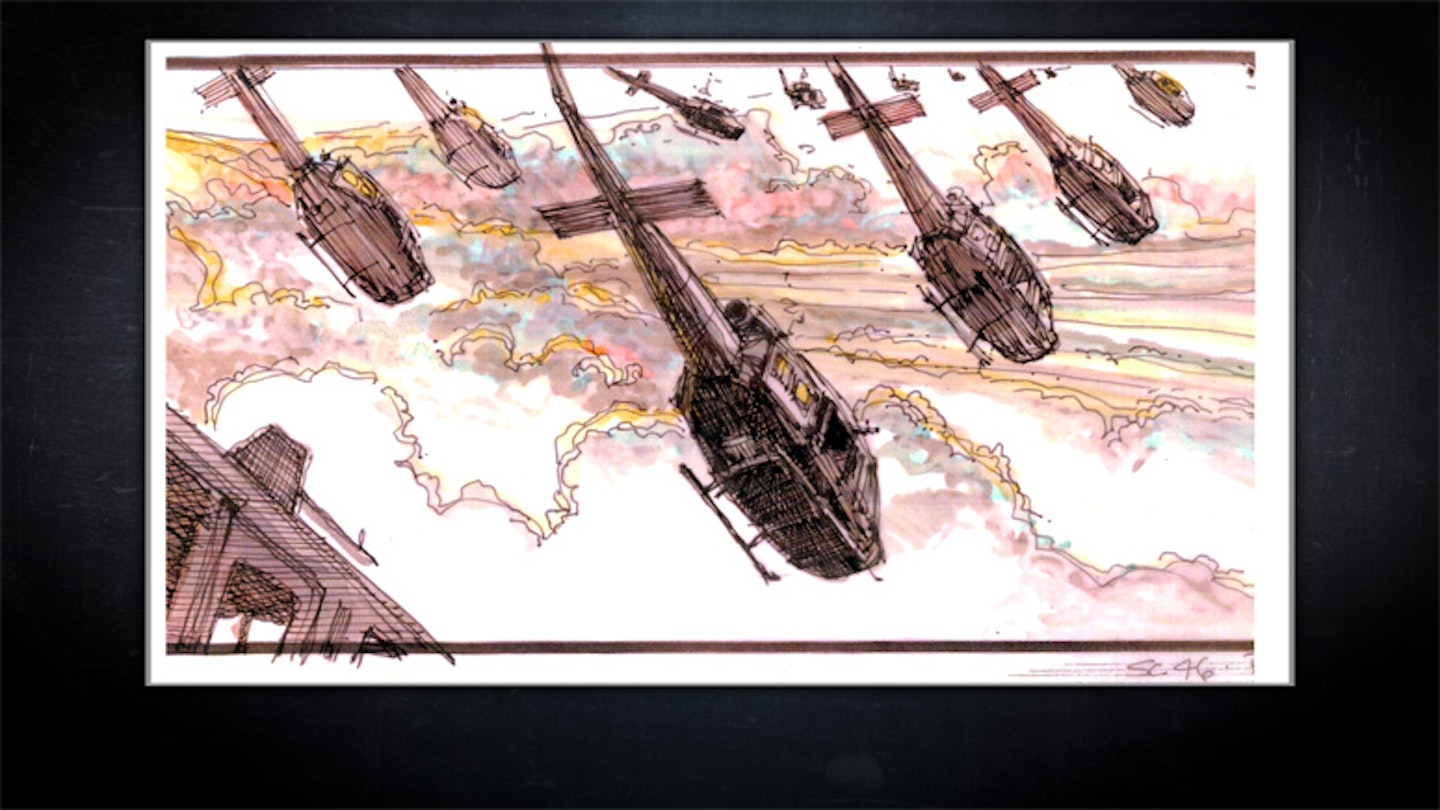

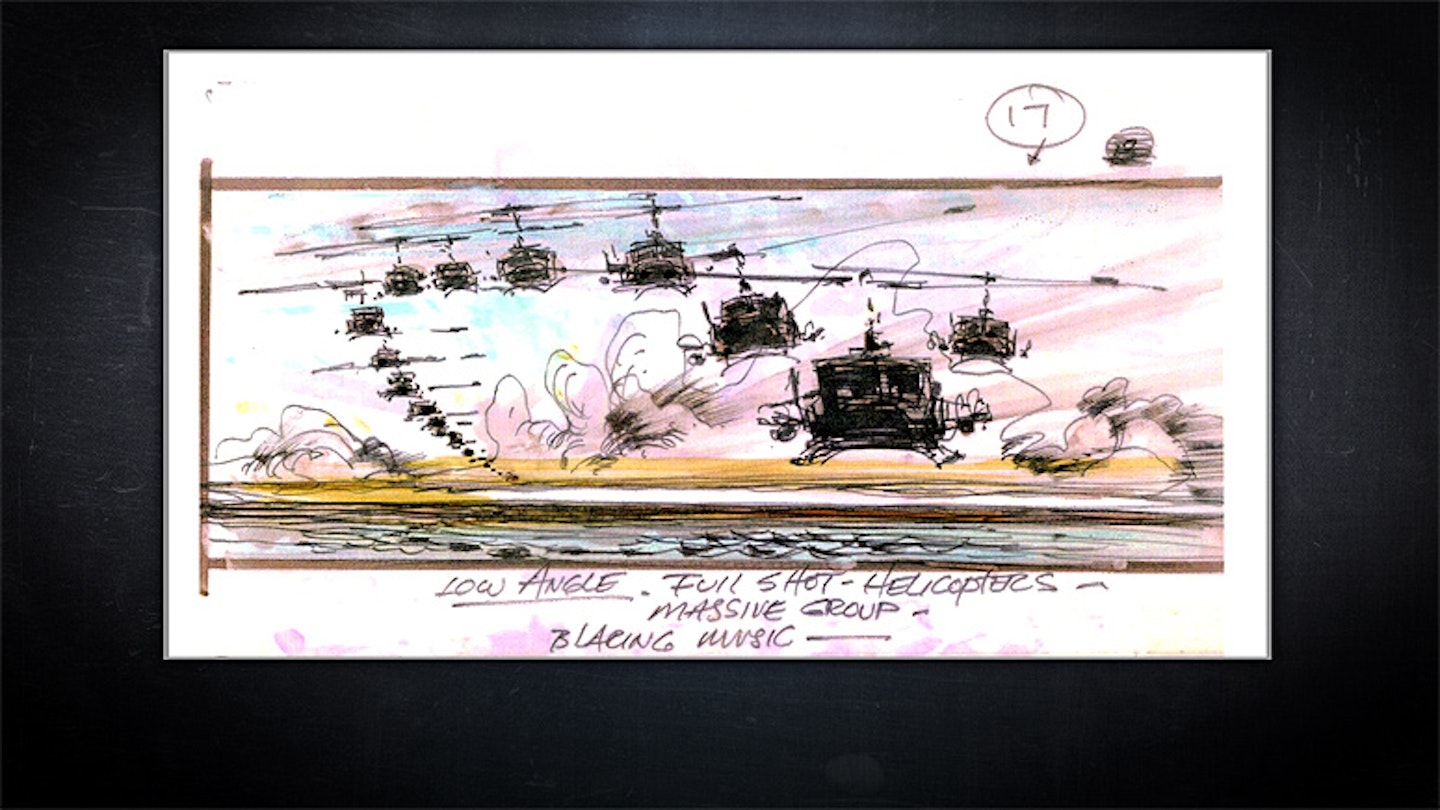

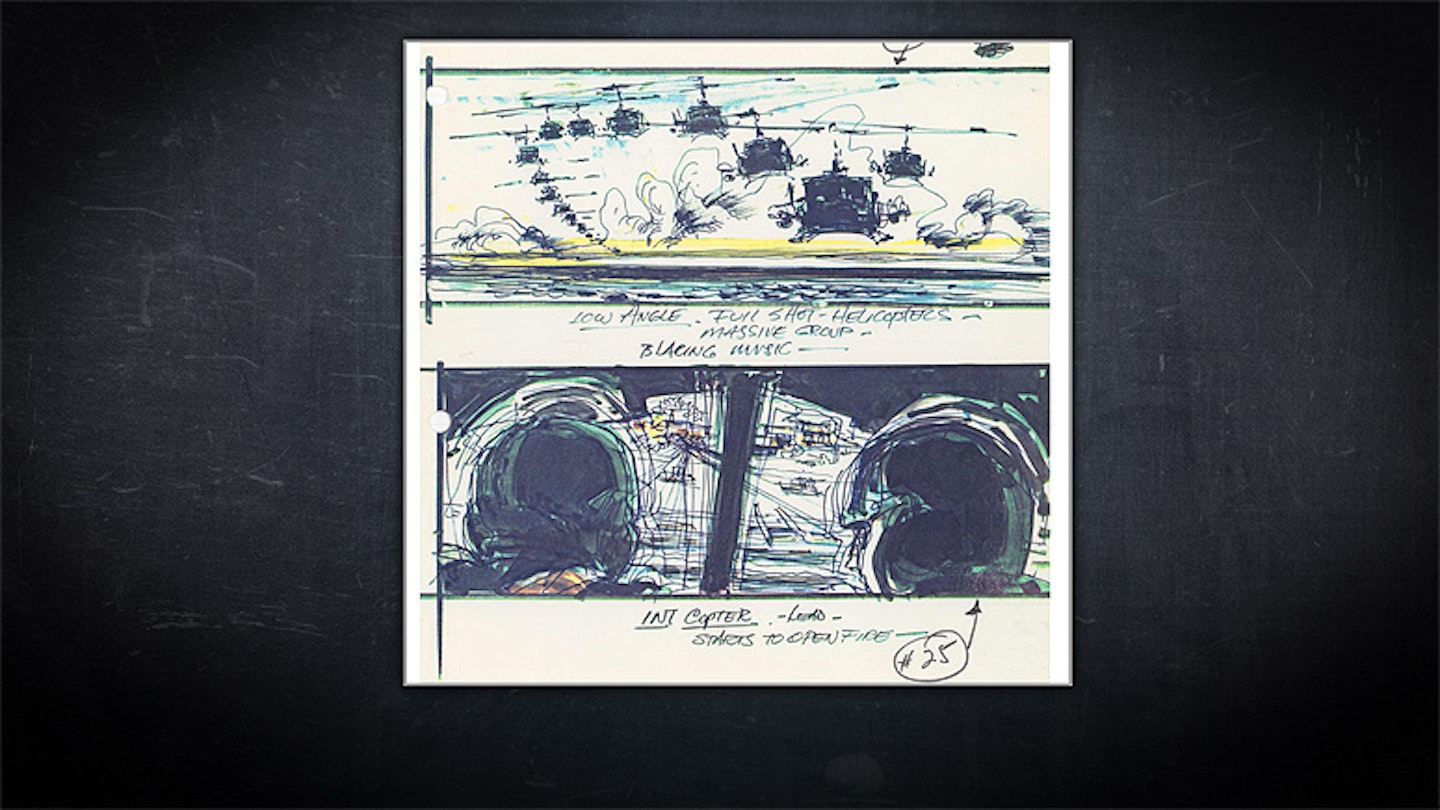

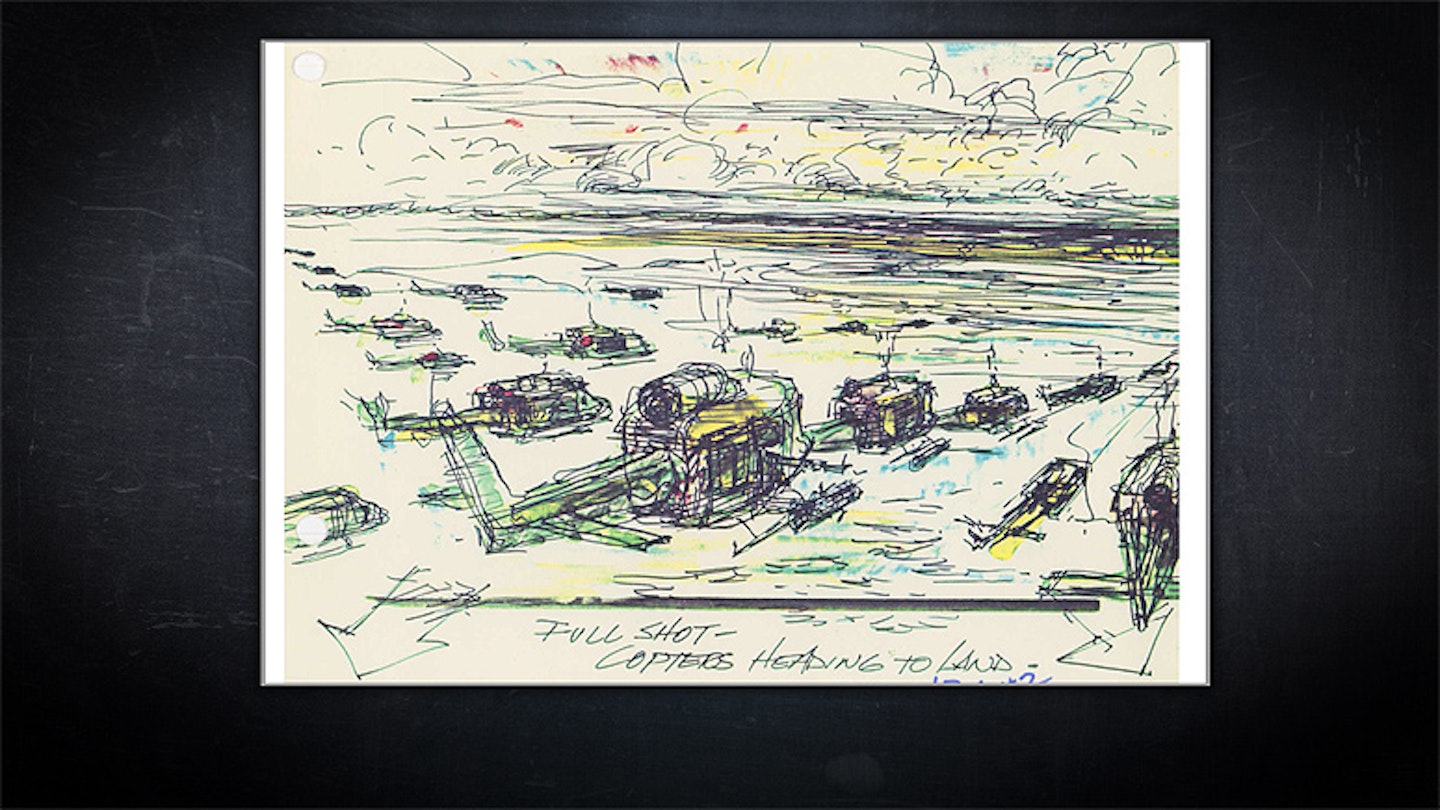

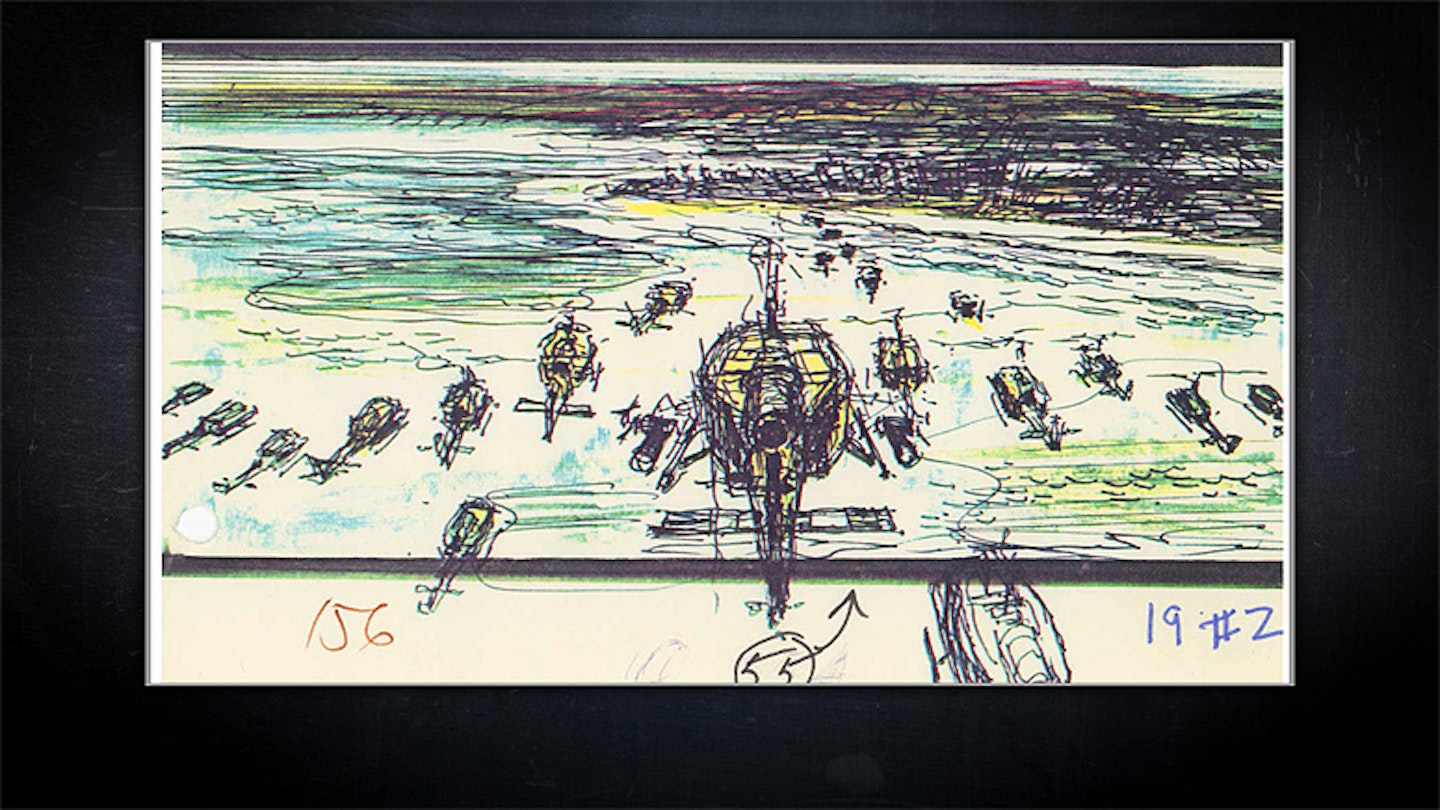

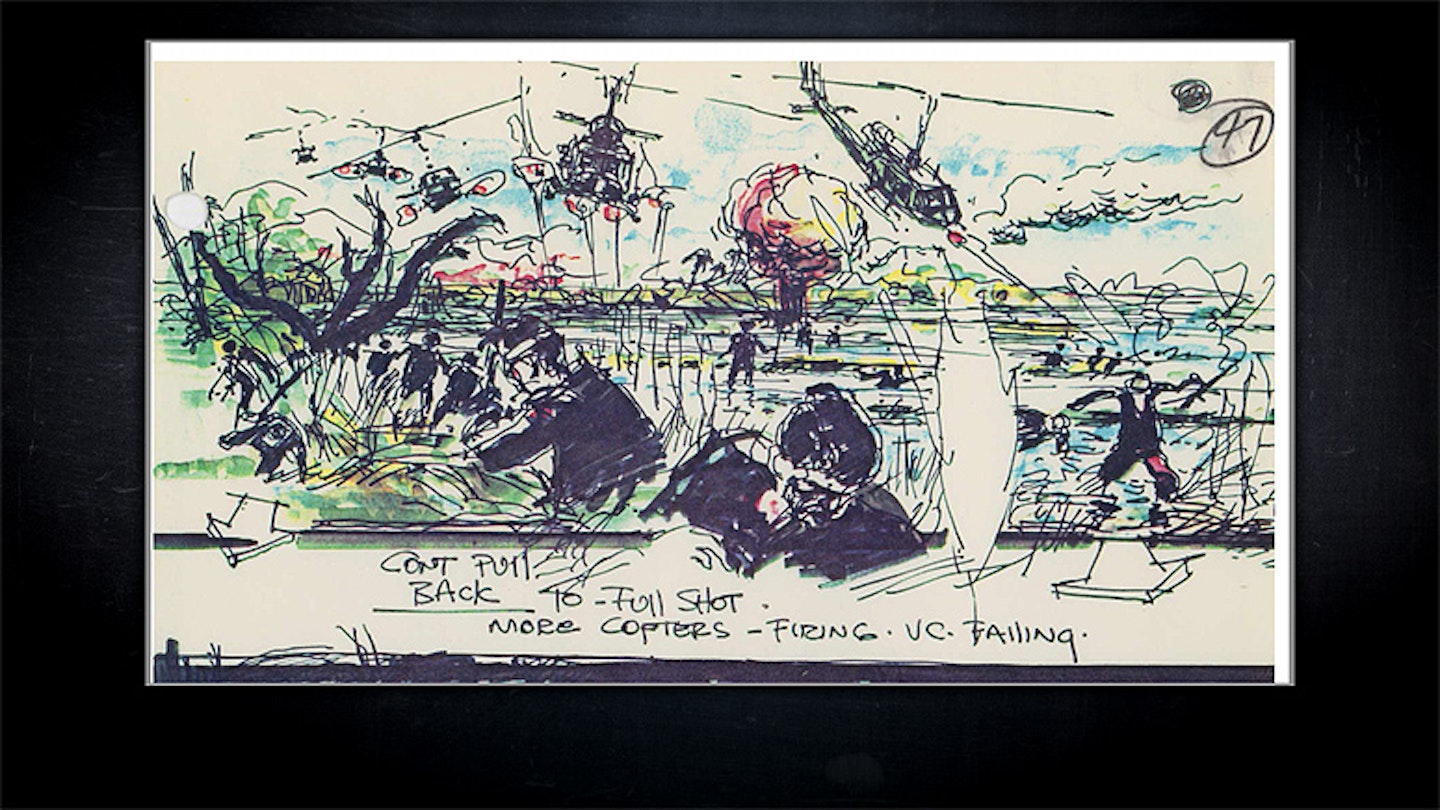

In retrospect, the tightly-packed swarm of choppers on this storyboard looks like wishful thinking. On the rare occasion Coppola could cobble together as many as 15 Hueys, the Philippine Army pilots' habit of flying them out of frame kept causing problems. "They were good people", says Claybourne, "they just weren’t movie pilots. This was a 2:35 frame so it was wider but lower, and it was hard to get them to fly within that frame. We had to drag them down to the ground and tell them that they’d have to go up and do it again'. Remember, there were no digital effects: if you see 14 fourteen helicopters, that’s how many there were. It wasn’t like Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor."

The AirCav attack was filmed a few weeks before Typhoon Olga struck, but with Martin Sheen freshly arrived as a replacement for Harvey Keitel (ten days after Keitel left) and the movie already over budget, things were stressful on set. “We were working six days a week and Francis was going through this really tough time," reflects Claybourne. As production assistant he'd received what he likens to a series of battlefield commissions and was soon working closely with the director. He had a box-seat view of the strain on Coppola. "It’s like as an artist reaching a point in a watercolour where it looks like you’re going to fuck it up and you have to paint through it until you reach the other side. He reached that point in the movie.”

While Claybourne prepped the choppers on the ground, dishing out helmets to the cast and extras before they mounted up and fixing M60s to the side of the Hueys, Dick White, the movie’s military advisor and one of the half dozen Vietnam veterans on set, took charge in the air. “Dick was a Cobra gunship pilot in Vietnam,” explains Claybourne. “He had a radio and would speak to me on the ground and talk to the jets, and I was next to the camera on the ground talking to guys on the ground. Depending on the day, we had a couple of ‘loaches’ [Hughes 500s], and we had US pilots to fly them, because American pilots were a little looser.”

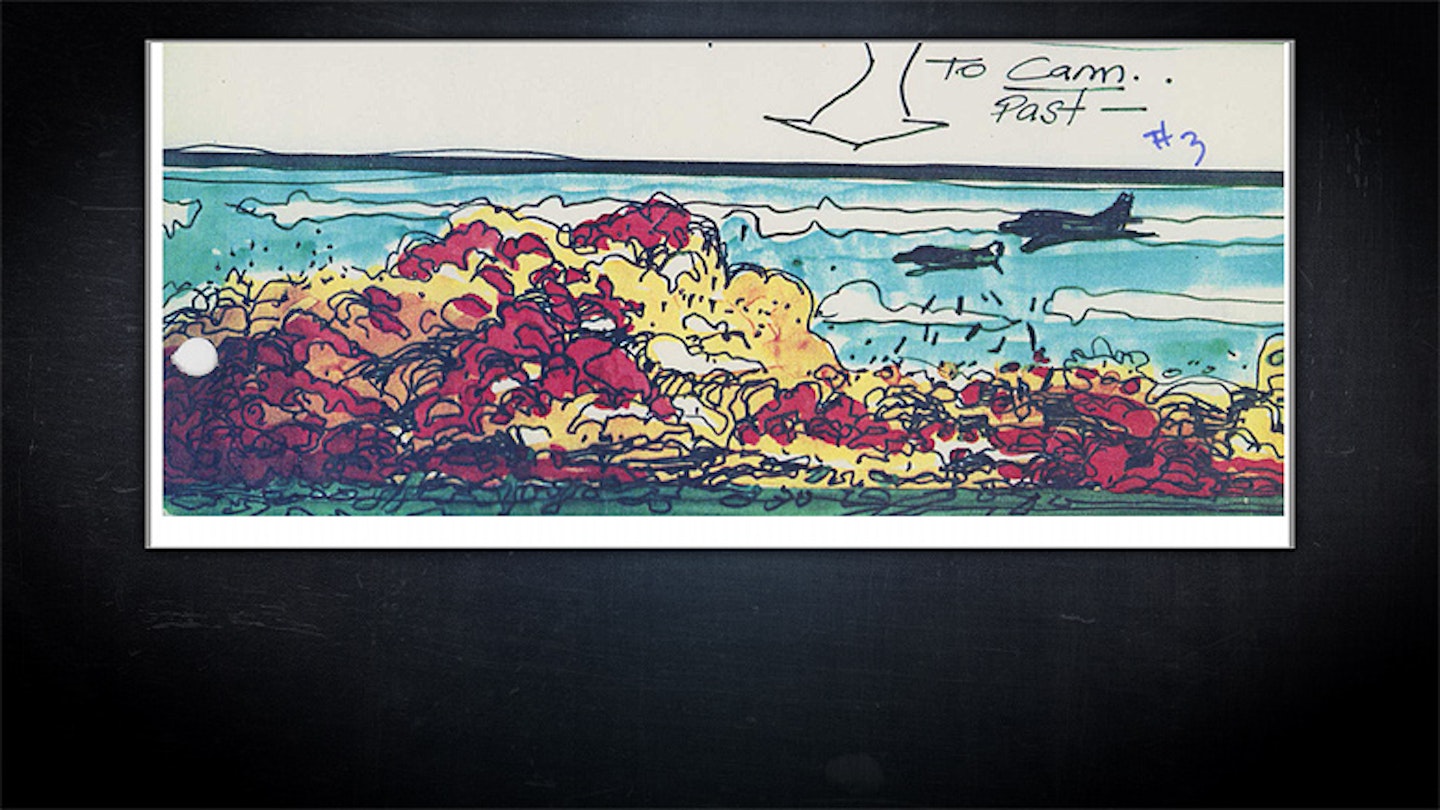

Effects guru A.D. Flowers, another Godfather alumnus, laid down more than 1200 gallons of gasoline in a ditch at the tree-line to prepare for the coup de gras, the napalm strike Kilgore calls in to take out the Viet Cong mortars and pave the way for his surfing safari. On May 7, four Philippine Air Force F-5s flew over, dropping dummy canisters and the whole lot went up in a fiery inferno. Thankfully there was no Tropic Thunder-style snafu. Across the lagoon Coppola “felt a strong flash of heat”.

Finally the surfers would be the chance to show their stuff... only, well, not so much. "There’s a great story about the surfing," Claybourne laughs. "We couldn't shoot the scene when we wanted to, so these two surfers we had on weekly contracts had to hang around for weeks and weeks, only when we finally got around to shooting the scene the guys couldn’t surf! We had to get a couple of the stunt guys to do it."

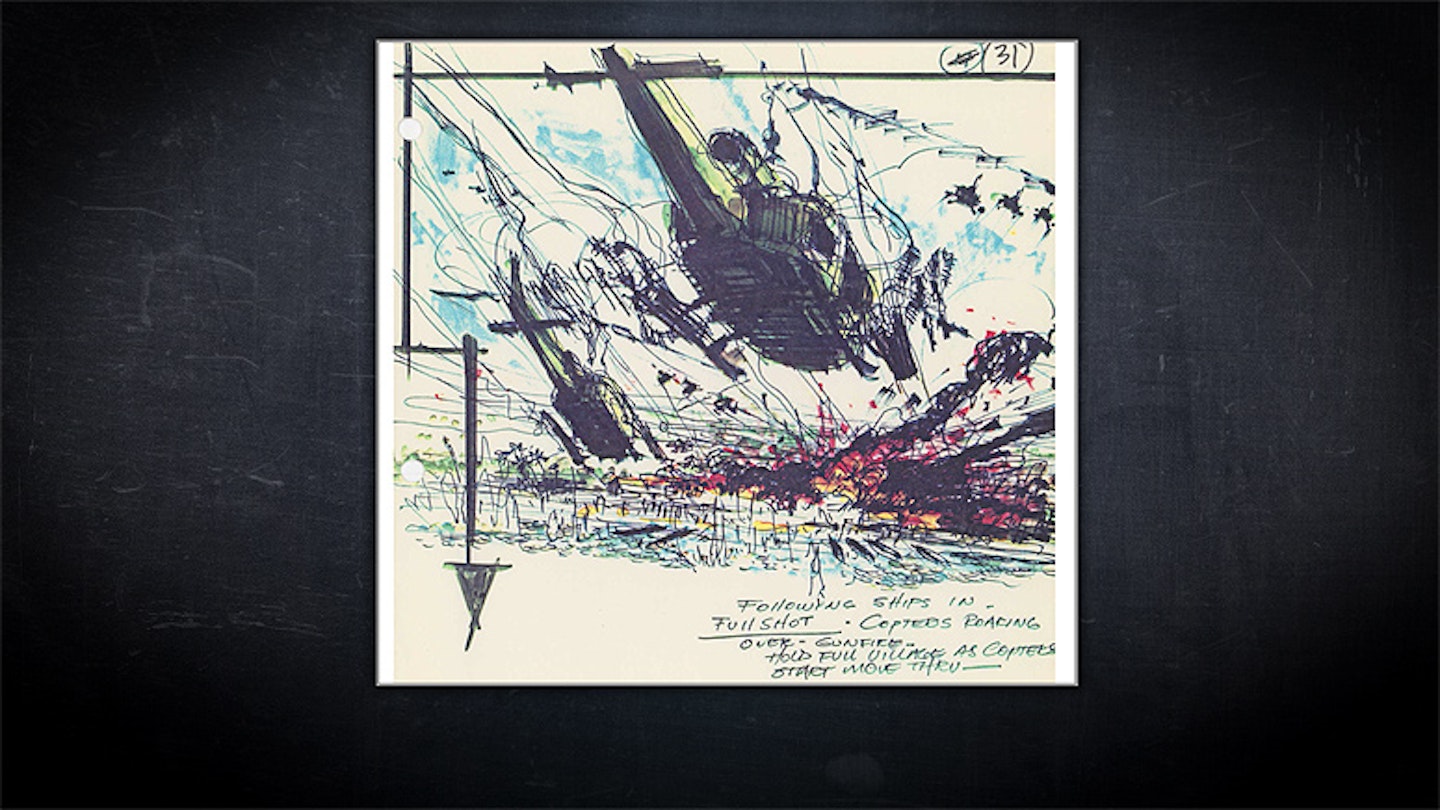

For all the pyrotechnics involved, the most explosive element of the scene remains Robert Duvall's Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore. He was a composite of several characters, including John B. Stockton, Colonel in the 9th Cavalry Airmobile in Vietnam (sample quote: “You wanted every member of the unit to start believing that he’s in the best unit in the United States Army. We’re different. We’re different because we’re better.”) and legendary infantry general James Hollingsworth (call name: 'Danger 79er'). They'd have done well to be quite as nutso as Kilgore - surfboard, neckerchief and all. This storyboard post-dates his original incarnation as 'Colonel Kharnage' and plots the moment just after the Viet Cong grenade incinerates a grounded Huey.

The 'copter explosion was arguably the most dangerous stunt in the sequence but the cast and crew were on edge throughout. “What I remember about the village shoot is that even though they weren't shooting real bullets, it was dangerous," remembers Claybourne. "The good news was that we shot the movie for 238 days and nobody got killed, but we had some pretty close calls." Dick White had a particularly close one when a stone narrowly missed the rotor blades of his Hughes 500. "Jerry [new assistant director Ziesmer] and Larry [new second AD Franco], did an amazing job working with Dick on those big first-unit helicopter scenes."

Of course, Lance Johnson never got to surf. Willard and the PBR street crew escaped (with or without Kilgore's surfboard, depending on which version you're watching) and the shoot moved on, bringing far more than its share of pinch-yourself moments for the Vietnam vet. "I realised that ten years previously I'd been in Vietnam trying to kill these people and now here I am here filming them," Claybourne tells Empire. "It was a bizarre moment – an out-of-body experience. I'd never dreamed in a million years that I’d make a film about it in that time period. [When Apocalypse Now was released] I watched it in a theatre in New York – the name of it slips my mind – and I sat there in tears. It’d been so long, we’d worked so hard and it was just hugely emotional. It must have been extraordinary for Francis. He didn’t realise he was making a great movie. He kept saying, “I’m making a piece of shit...”

Apocalypse Now is in cinemas on May 27