%20](http://www.empireonline.com/movies/features/empire-80s-month/empire-80s-month?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

“I’m lucky: I have movies that still play,” John Landis tells Empire over the phone from his LA residence. That’s one hell of an understatement. From The Blues Brothers to Coming To America, Trading Places to ¡Three Amigos!, Landis rocked the ’80s, creating a string of terrific comedies that today are cherished as iconic all-timers. The decade wasn’t always a fun one for the director — from a fatal accident on-set of his segment of Twilight Zone: The Movie to a falling out with Eddie Murphy, he had his fair share of misfortune. But it would be remiss to celebrate the period without hailing Landis, still a motormouth film buff with an anecdote for every occasion, as one of its heroes. Read on for his memories of crafting big-budget laughs, coping with Murphy’s entourage and casting an actor everyone thought was dead.

Note: ¡Three Amigos! is not included in this conversation, as it’s covered pretty comprehensively in this reunion piece.

You began the 1980s with a monster of a movie, The Blues Brothers. How did it come about?

My next movie after Animal House was going to be a thing called The Incredible Shrinking Woman. Lily Tomlin, who was then at the height of her success, and her partner Jane Wagner came to me with the script. It was a big picture. We had permission to stage an assassination on the steps of the Capitol Building in Washington. There was a chase with a gorilla through the Smithsonian. It’s really amazing what we could have done. Then Moment By Moment came out, Lily’s film with John Travolta, and it was a disaster. So much so that it killed Travolta’s career; he didn't come back until Pulp Fiction. The studio turned to me — I’m making this $14 million movie — and said, “John, we need to make it for $6 million.” This was a movie where the protagonist is shrinking the whole movie, like Ant-Man! I said, “I can’t.” And they shut it down.

We waited and waited for Danny Aykroyd's Blues Brothers script. Finally he threw it over the producer's garden fence.

What happened in the meantime is that Danny Aykroyd and John Belushi had started this thing where they would perform with blues bands as these characters, John and Elwood. Howard Shore is actually the one who said, “You should call yourself the Blues Brothers.” Steve Martin asked them to open for him at the Universal Amphitheatre in LA; the show was recorded, released as an album and went triple-platinum. So when Moment By Moment came out, John and Danny were the stars of the number-one TV show in the country, Saturday Night Live, John was the star of the number-one movie in the country, Animal House, and they had the number one record in the world. The studio came to me in late 1979 and said, “Can you have a Blues Brothers movie in theatres by August?” I said, “Sure!” But there was no screenplay.

Were you panicking?

I was going crazy, because we were just shot into space. And rather than God, it’s Danny Aykroyd who works in mysterious ways. He went off to write the script, while we all fretted and waited and waited, and finally he threw it over (producer) Bob Weiss’ garden fence. It was huge, like a phonebook, brilliant but insane. Each member of the band basically had his own movie, even though none of those guys were actors. The thing was unshootable. I was like, “Yikes!” So Danny and I agreed that I’d cut it down and rewrite it.

The Blues Brothers became notorious for being an out-of-control production…

Well, there was never a budgetary process. They just said, “Go!” Around this time, there were five Hollywood films in production that broke the $24 million mark in terms of budget. $24 million was a magic number — that was Cleopatra. That’s the number that sunk [20th Century] Fox, that forced a studio to sell its backlot. Those five movies were 1941, The Blues Brothers, Heaven’s Gate, Apocalypse Now and Star Trek. And the story in the press became, “Hollywood out of control!” We were ginormous, there’s no debate about that. We were shooting in downtown Chicago, doing these massive military operations with 110 cars whizzing about at 100 miles an hour. Hundreds of extras and stunt people. Gosh, in one scene we had almost 500 PAs, because we had to make sure there was someone with a walkie-talkie at every possible alley or entrance to this street. So anyway, while we’re doing these things — this is before CGI, so it’s all real — studio head Ned Tanen was being grilled by reporters: “What the fuck’s going on in Chicago?” He said, “Well, the budget’s $11 million.” That got printed in the trades. And I remember Bob Weiss coming up to me on set and whispering, “I think we’ve already spent $11 million!”

It all worked out in the end, though. The movie’s still beloved, and there’s not only a sequel but an in-development animated series…

Danny is evangelical about this stuff. The whole "mission from God" thing is me making fun of him, because he was so serious about the music. My favourite line in the original film, which is pure Dan Aykroyd, is when the woman says, "Are you the police?" And Aykroyd says, "No, ma’am, we're musicians." But the sequel was very, very, very truncated and fucked up by the studio. That’s an old horror story, that one. By the time they were done with us, they’d just castrated the whole thing.

You took a break from pure comedy with An American Werewolf In London. Then you made a triumphant return with 1983’s Trading Places.

That was a script originally written for Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder. And then Richard unfortunately set himself on fire. Jeff Katzenberg at Paramount gave it to me and I was excited by it, because it was very old-fashioned in its structure. Essentially it’s a ’30s screwball comedy. All those pictures — My Man Godfrey, the Leo McCarey and Preston Sturges pictures — dealt with class, and Trading Places is all about class. In America, it doesn’t have to do with your ancestors; it has to do with your wealth. The only thing I added to contemporise the movie was the language and nudity.

Ronnie Barker would not work more than seven miles from his house, just outside of London.

How did you wind up casting Eddie Murphy?

He’d just wrapped 48 Hrs. and the studio was very unhappy with him on that movie — they didn’t like the dailies. Then they previewed it and the audiences just loved Eddie. Based on that, they said, “Hey, what about putting him in this dead movie we had for Pryor?” So I flew to New York and met with Eddie, who was on Saturday Night Live at the time. He was terrific, I was very pleased with him. He was 19 or something, just full of beans. What they didn’t like was my decision to cast Danny Aykroyd. John had died and Danny then made a movie called Doctor Detroit, which tanked. So the conventional wisdom was that Aykroyd without Belushi didn’t mean anything. Fortunately, I won that argument. Danny is such a unique and wonderful actor. I mean, look at Elwood and then look at Louis Winthorpe III. They have absolutely nothing in common. They’re from different planets!

Didn’t you have other problems with casting on Trading Places?

I tried to get Ronnie Barker to play Coleman the butler, the part played by Denholm Elliott, but he would not work more than seven miles from his house, just outside of London. What really got me in trouble was Jamie Lee Curtis, because up to that point she had only done horror pictures. But Jamie did a terrific job. She somehow made her part, the hooker with a heart of gold, almost believable! And up until then she’d always had longer hair. My wife Deborah, the costume designer, said, “You know, John, she’d look better if you cut her hair really short.” So that’s where her short hair came from. Which we then covered with that terrible wig for part of the movie!

You also ended up casting two Hollywood legends, in the form of Ralph Bellamy and Don Ameche.

I actually cast Ray Milland in Don’s part, but he couldn’t pass the insurance physical. That was quite a setback, because we were very close to shooting. So I was at Paramount with the casting person, going, “Okay, I need someone who was a movie star in the ’30s and ’40s…” Then I had a brainwave: “Don Ameche!” The casting person said, “Don Ameche’s dead.” So we looked it up and the last thing Don Ameche had done was an episode of The Love Boat, two years earlier. I was like, “Shit.” We called the Screen Actors Guild and they said there was no agent listed for him. They sent the residual cheques to his son in Arizona. Eventually we tracked him down and he was alive. But the studio said, “Why are you paying for an actor everybody thought was dead?” They were so aggravated that they took a couple of million bucks off the budget.

What’s your favourite memory of the shoot?

We were in Philadelphia and it was fucking freezing. Oh man, it was cold! I was in a car, wearing a parka and looking like the Michelin Man, towing this giant Rolls-Royce with Don, Eddie and Ralph in the back seat with a space heater, all toasty. And I was listening through a headset to the three of them talking. Ralph said, “You know, this is my 99th motion picture.” And Don said, “Well, it’s my hundreth motion picture.” And Eddie said, “Hey, Landis, between the three of us we’ve made 201 films!”

You went on to make Into The Night. That’s an underrated black comedy, with an amazing cast.

Into The Night was a movie I enjoyed making. Michelle Pfeiffer was wonderful and David Bowie was wonderful. What was weird was that it was a bomb. It was my first real bomb. It was weird, because I thought, "I did everything I usually do." But it was a good experience. I loved working with B.B. King. I had the idea — it's been done since with Eric Clapton and Ry Cooder, but I was the first one to do it — to have B.B. sit down with the movie and his guitar. He watched it twice, then the third time he played his guitar along to it, and the score was written around that. The music videos for the film are B.B. performing in a club with people dancing, but his band is Jeff Goldblum on piano, Eddie Murphy on drums, and the horn section is Michelle Pfeiffer, Dan Aykroyd and Steve Martin. We did two of them and they were very entertaining.

Spies Like Us is a wacky spy comedy, with bit-parts for Sam Raimi and the Coen Brothers. How did it come about?

That experience was in the middle of the Twilight Zone aftermath. (Actor Vic Morrow and two children were killed when a stunt went wrong; Landis subsequently was taken to court.) It’s a horror story. Warner Brothers, who made The Twilight Zone, were acting despicably, but there was this project, Spies Like Us, which Danny had originated and which the studio sent to me. I was thinking, “Warner Brothers? Fuck them.” But my attorneys said, “You have to make this movie. Because many of the studio’s positions will be obviously false if they give you $20 million to go make a film.” So that’s what happened. I was sort of reluctant. But then I read the script, and realised here was an opportunity to do a road picture. In fact, Bob Hope’s in the movie!

Given Aykroyd and Chevy Chase are hoping to work together again, we’re guessing they had a good time?

They were both big stars and obviously had known each other for a long time. It was funny, because Danny had starred in Trading Places, Ghostbusters and The Blues Brothers, and all three of those movies were big hits in the UK. So when we got to Pinewood to start filming with a British crew, everybody knew who Danny was, but nobody knew who Chevy was. It sort of drove him crazy. But he was fine. The picture was pretty low-budget, but we went around the world: we shot in Norway and Morocco and Washington DC and Palm Desert in California. What’s more fun than to be in the Sahara desert or the beautiful fjords of Norway? And I got to work with Derek Meddings, one of the legends of special effects, who did all those Gerry Anderson miniatures. There's tons of stuff in that movie that I don't think you'd even realise are miniatures.

The Paul McCartney theme tune is one of the film’s more peculiar elements. Was that your idea?

Not at all. The movie was finished, when I got a call from Mark Canton, the studio executive at Warner Bros., saying, "John, guess what! Paul McCartney's going to write the title song for Spies Like Us!" I said, "What are you talking about? It's finished. We have answer print. It's done." He said, "No, no, John, you don't understand. Paul McCartney is going to write the title song for Spies Like Us!" Well, what had happened is Paul had contacted Warner Brothers and offered a song for free. I think he’s a genius — I saw The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl when I was 15 — but it was so out of the blue. An hour later, the phone rings and my secretary answers it. She comes into my office and she’s literally shaking with excitement: “John, Paul McCartney is on the phone!” I picked up the phone, feeling giddy but determined to talk him out of it. But he was so friendly and said, “Let me just do one and you decide if you like it. How’s that, mate? Is that fine?” And I just folded. My voice went high-pitched, like the bit in Fantasia where Mickey goes, “Thanks, Mr. Stokowski!” When it came in, I thought the song was silly but it had a rocking chorus. So I ended up using it over the end credits, arranged so the chorus is first and the regular song only starts up as people are leaving the theatre. It’s one of the most remarkable things in my career: I've worked with David Bowie and Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles and Erykah Badu and BB King and Eric Clapton... It's kind of extraordinary, the musicians I've worked with. I'm very lucky.

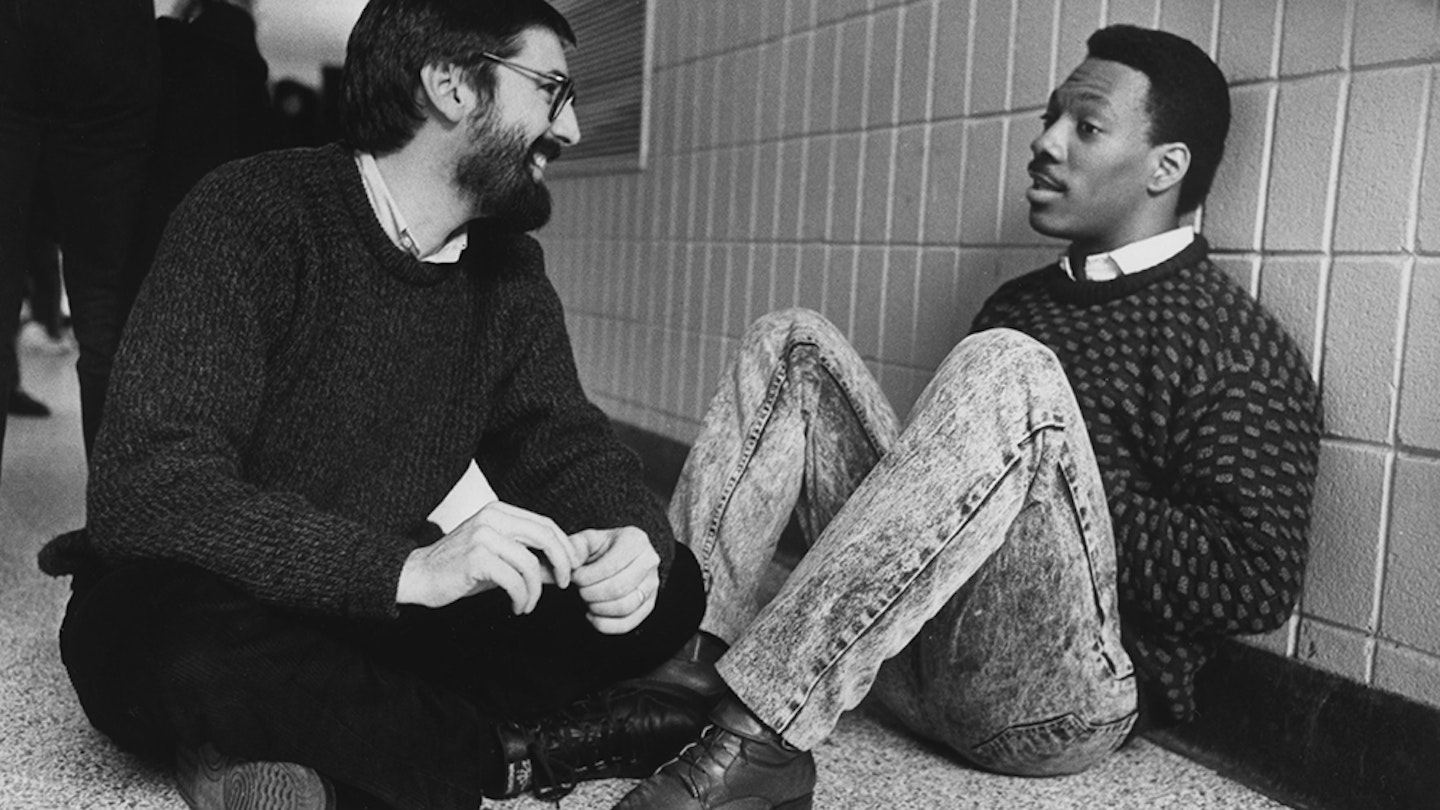

Finally, at the tail-end of the ‘80s, you reunited with Eddie Murphy to make Coming To America. Was he a different person at that point?

He was different. He was still wonderfully talented, and working on the floor with him was still a lot of fun, but otherwise he was distant and removed. I’ve worked with a lot of people who have experienced that level of fame, and it’s a very surreal and difficult thing. He had a big entourage on Coming To America, his posse. He actually got mad at me when we were shooting in Madison Square Garden. There was ice down ready for an ice-hockey game, with a board three feet wide laid across it. And at one point I looked down and saw 15 guys trying to all walk across the board together, with Eddie in the middle. It looked so funny that I started laughing, but he wasn't amused. I never found out what inspired it, but later there was one moment where he exploded at me. It’s blown over, though. We made Beverly Hills Cop 3 together and he now lives up the street from me.

Wasn’t Coming To America his idea in the first place?

Eddie had this idea — basically Cinderella, an African prince comes to America to look for his bride and goes to Queens. When he pitched it to me, I went home and said to Deborah, my wife, “What do you think about this?” What she got right away was that it’s a fairy tale, a Maurice Chevalier/ Jeanette MacDonald movie. And Deborah's really responsible for what Zamunda is. She designed all those beautiful, elegant costumes. The exciting thing was that up until that point, in every studio film that starred people of colour, their colour was a plot point. Eddie is “the black guy” in 48 Hours. Sidney Poitier was always “the black guy”. But with Coming To America I realised that the colour of their skin has fuck-all to do with the story. It’s a fairy tale. There are only three or four white people with dialogue in the movie, yet people don't think of it as a black movie, and that's wonderful, because they're just people in it, this silly little romantic movie.

It was the first time Murphy played multiple characters in a film…

By the time we were finished, I think Eddie played seven characters or something. There are scenes in that movie where there are six people and three of them are Eddie! That whole thing started because in pre-production I happened to see an African-American filmmaker on TV, talking about minstrel shows and blackface, and he said some things that were very ignorant. He said blackface was a Jewish invention, done by Jewish comedians. So I came in the next day and said, “Eddie, can you do a Yiddish accent?” I knew he could do anything. I gave him some tapes to listen to and he got the accent down. Then I called Rick Baker and said, “Hey, Rick, I’ve got a challenge for you.” He did a cast of Eddie’s face and a make-up sculpture and we did a test that was so fucking funny, with Eddie just improvising. Once Eddie saw that he could physically play the role, he said, “I want to be the old barber too!” And it went on from there. I used Eddie’s brother Charlie, who really resembled Eddie from the back, as a double. The make-up freed Eddie in some way, because from then on it became a gimmick. And fascinating, because if you look at The Nutty Professor, which he did soon after that with Rick Baker again, when he’s the fat professor he’s wonderful. But as the alter ego he’s not very interesting. It’s like Bowfinger — when he’s the brother he’s fabulous, but when he’s the movie star he’s boring!

This business is strange: you have very involved relationships with people and then you never see them again. It’s like summer camp.

Do you keep up with any of the ‘80s comedy stars you worked with?

I see Eddie around occasionally. I drive by, we wave. He seems happy these days. He’s certainly rich! Danny, I’m still talking to all the time. I saw Steve Martin the other day. This business is very strange: you go to some place and have this intense experience and very involved relationships, and then you go home and may never see the people again. It’s like summer camp.

And finally, when are we going to see another John Landis film?

I’ve got several things cooking, but the truth is nothing is real ’til it’s real. I had a very aggravating time in post-production on Burke And Hare, fighting with the producers about the film, and at this point in my life I’m only going to do something for fun, or if it gives me the opportunity to do something really good. I did just do a secret thing that’s really cool that you’ll see next year. But what really excites me these days is television. I have one idea, something I really want to do, that’s based on a famous book by a famous author. With a mini-series, you can really do a book justice now.