Alderson (Ritchings), a nervous, bald man in prison clothes walks through a strange square-shaped room, and is surprised by a descending razor-wire grille that turns him into a man-shaped tower of cubes that fall apart in disgusting fashion.

Before its credits, Cube has shown us the only set we're going to see and established that hideous abuses can befall its human characters. It's an eye-opening kick-start and clues the audience in to who is really behind the vast trap machine in which the cast are struggling. We later learn that every one of the subjects has a predestined part to play in the drama of escape, and poor Alderson's role was to make a dramatic point for us.

Early on, as the characters argue about whether their situation has been engineered by the military-industrial complex ("Only the government could build something this ugly"), space aliens or "Some rich sicko" the canniest of them advises "Take a good, long look-see... because I've got a feeling it's looking at us." Those unseen watchers, who never show up on screen, are — of course — the audience; and the elusive point of the exercise is to provide us with an hour and a half of puzzlement and entertainment as we watch human rats battle a fiendish maze.

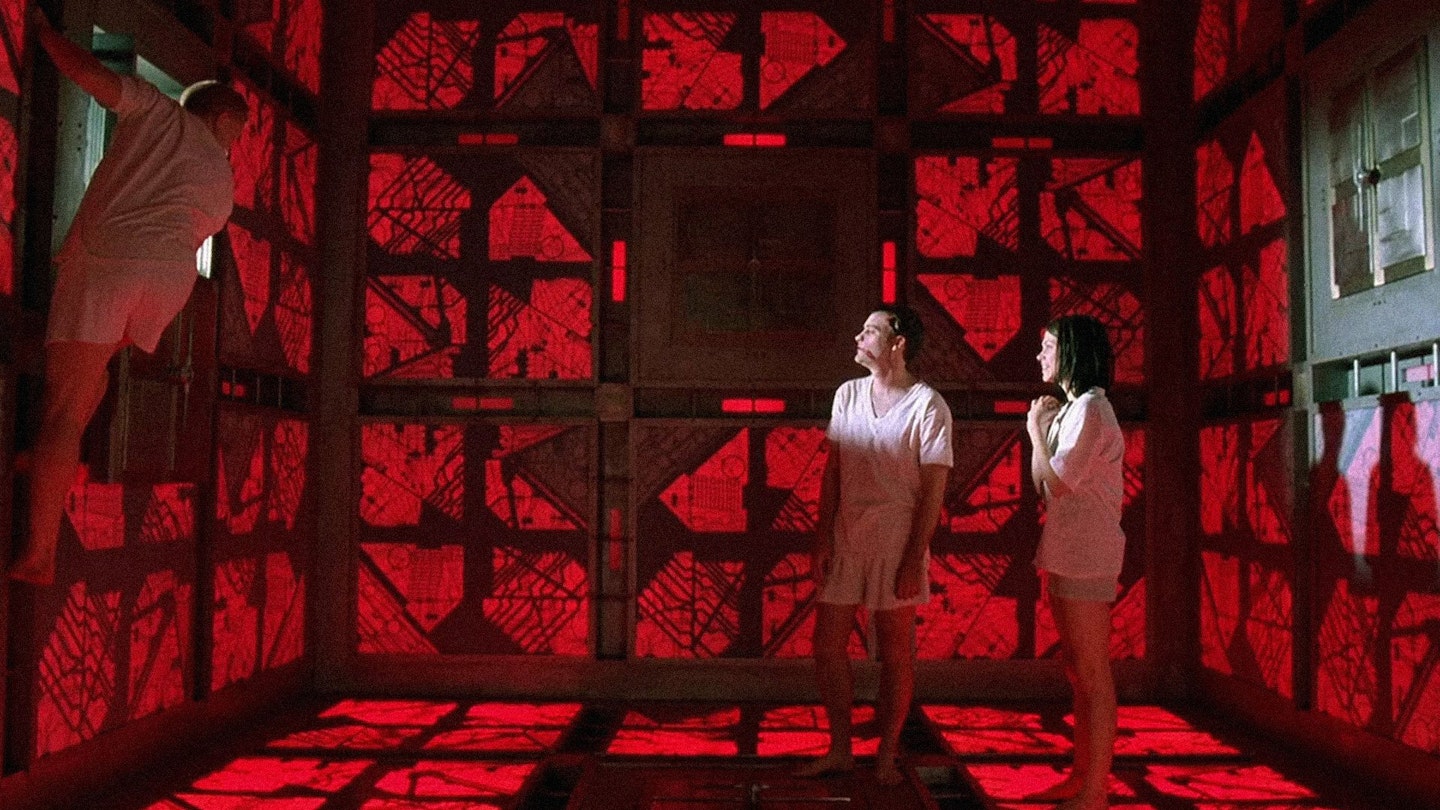

Director-writer Vincenzo Natali warmed up by making Elevated, a short film about three people trapped in a lift. Cube expands the scale with four extra characters and a single set that can be cannily relit to stand in for an assortment of the estimated 17,576 rooms within the master cube.

The plot is simple: seven people wake up within a vast maze that resembles (more closely than it at first seems) a giant Rubik's Cube. Each room is a cube within a cube, with six doors opening to other rooms, but a percentage of the rooms are equipped with deadly booby traps which soon claim the life of renowned prison-escapee Rennes (Robson). Each of the surviving group has a talent: cop Quentin (Wint) is obsessive about making it to freedom, student Leaven (DeBoer) is a maths prodigy; loser Worth (Hewlett) was unknowingly part of the design team who assembled the cube; conspiracy theorist Holloway (Guadagni) is a doctor with the right mindset to expect this sort of thing ("Nobody's ever going to call me "paranoid' again"); and autistic Kazan (Miller) is a savant who can out-calculate Leaven when the stakes rise.

As they try to solve problems, alternating between co-operation and conflict, they gradually make their way towards the perhaps-mythical exit, and learn about their own resources and failings along the way. Cube was one of two 1998 science fiction movies named after three-dimensional shapes, and cost roughly nothing next to Barry Levinson's inflated Michael Crichton movie Sphere, which falls into all the traps that the off-Hollywood effort knows to avoid: Natale sidesteps the big let-down that comes when the purpose of the artefact is laboriously explained in Sphere by simply not explaining who was behind the whole thing, and trusting us to concentrate on the character drama and the mind-puzzle at the heart of the script. It was also one of two 1998 independents to apply itself to mathematics as a well-spring of mystery and imagination, making for a stimulating double-bill with Darren Aronofsky's Pi.

The cast are the sort of faces who show up in Canadian-shot (South Park fans will notice a high "aboot" rate in the dialogue) trash TV like The Outer Limits, Forever Knight and The Hunger, and sometimes aren't quite up to scenes that call for subtlety as well as hysteria. But the non-star ensemble ensures a level of surprise about who of these characters — all named after various prisons — will make it through, with a couple of last-minute, against-the-cliche sacrifices. There's a clever arc as the very qualities — take-charge indomitability, quickness to action, determination to survive — that mark Quentin (the only black character) out as a hero at the beginning then turn him into the psychopathic menace who has to be ditched and bested so that the others can make it to freedom.