The mid-1980s did not represent a golden age of American filmmaking. The great directors of the previous decade were not on top of their game: Marty was drained, Francis bankrupt, Friedkin burnt out, Altman washed up, Roman on the run and Spielberg, seemingly having peaked with E.T., was in his literary adaptation period. Spike Lee and Jim Jarmusch were starting to produce interesting work in the low-budget, independent sector, but the medium was crying out for a figure with a distinctive vision and voice. David Lynch answered the call with Blue Velvet.

Lynch was an unlikely saviour. He'd made his breakthrough in 1977 with Eraserhead, a deeply disturbing, surreal nightmare of a movie. It was a cult favourite on the late-night circuit and with student film societies, and secured Lynch a switch to the mainstream with prestigious period flick The Elephant Man, which in turn earned him a Best Director Oscar nomination.

It seemed Lynch would be assimilated onto the Hollywood A-list, especially when he was given the reins of big-budget, long-gestating sci-fi epic, Dune. The resulting film, however, was a disaster, a turkey as unappealing as the one which came to life and bled all over the table in Eraserhead. Lynch's moment in the sun was over, but Dune did see him establish two key relationships - with producer Dino De Laurentiis and young actor Kyle MacLachlan.

While lesser moguls might have retreated to lick their wounds and blame their director, De Laurentiis hailed Lynch as a talent to rank alongside Fellini (with whom he had also worked) and bankrolled his next film to the tune of six million dollars.

Much happier working from his own script, Lynch delivered the film on time and within budget, without compromising his vision.Blue Velvet established the Lynchian style, introducing themes he would explore obsessively throughout much of his future career. With MacLachlan as his seemingly clean-cut alter ego, the former Eagle Scout from Missoula, Montana, probed the dark heart of small-town America.

Jeffrey Beaumont lives in a neighbourhood of white picket fences and manicured lawns, but when taking a short- cut home from visiting his hospitalised father, young Jeff finds a severed human ear. The model citizen takes said ear to the local police station but, though this satisfies his sense of civic duty, his innate curiosity is awakened and eager to know more. As Jeffrey tells Sandy, the sweet-natured high school girl and daughter of local cop Detective Williams, "I believe there are opportunities in life for gaining knowledge and experience, but sometimes that means taking a risk." Soon, this fresh-faced couple are conspiring to sneak into the apartment of nightclub chanteuse Dorothy Vallens, hoping to find clues that will help them solve the mystery: "Nobody would think two people like us would be crazy enough to do something like this," they cheerily decide.

In fact, Jeffrey's knowledge and experience arrives in the form of sadomasochistic sex with Dorothy and a life-threatening confrontation with her psychotic lover, Frank.

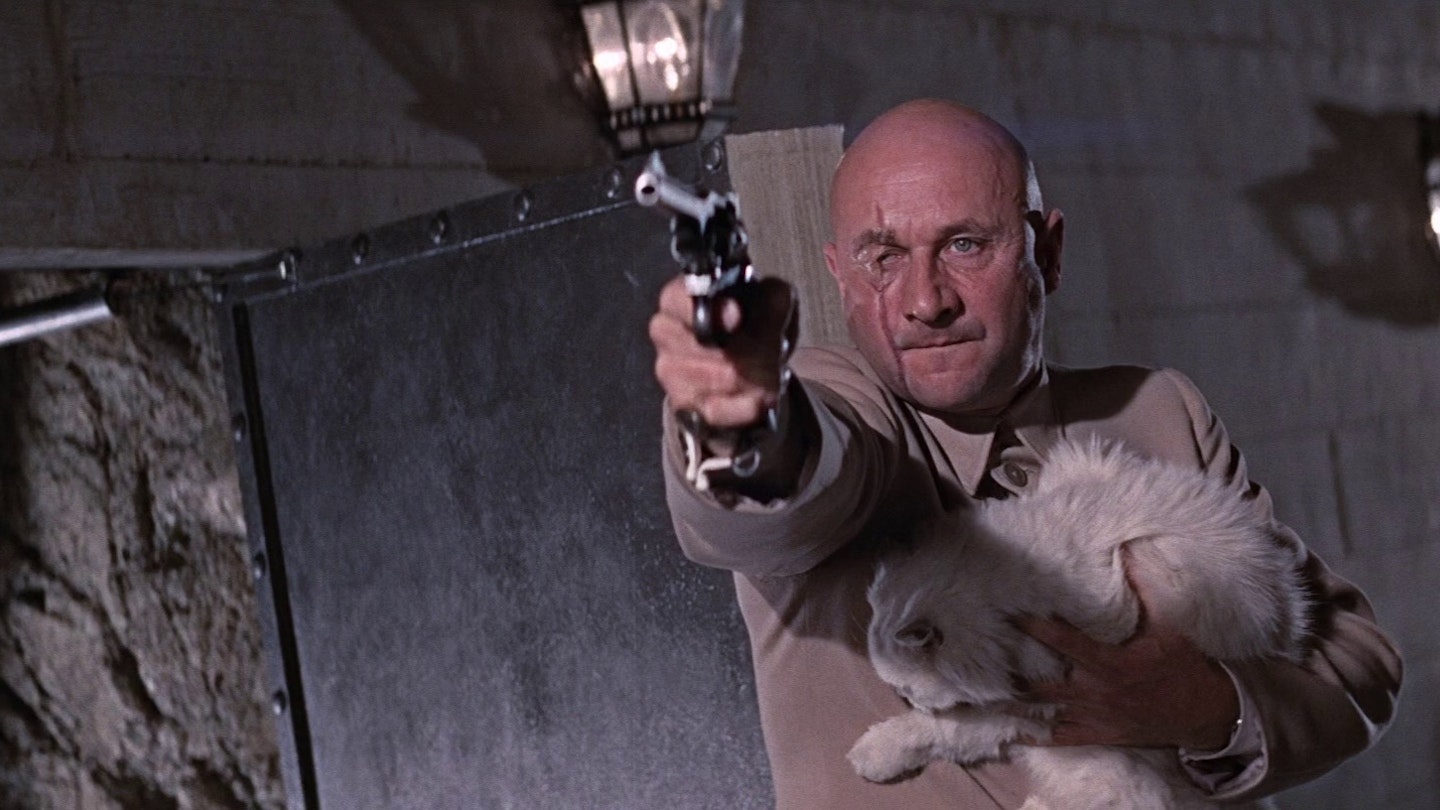

In a film of extreme characters and daring performances, no-one is wilder than Frank, no characterisation more "out there" than that delivered by Dennis Hopper. Nearly two decades on, and with a string of self-parodic rent-a-nut job gigs from Hopper to taint the viewer's perception, Frank remains an astonishing creation. He is a terrifying individual, perverse and brutal, with the attention span and tantrum capacity of a small child. Hopper seizes the role with relish, somehow avoiding going over the top despite screaming lines like, "Let's fuck - I'll fuck anything that moves," or responding to Jeffrey's request for a particular brand of beer with the immortal riposte, "Heineken? Fuck that shit! Pabst Blue Ribbon." After many drug-addled years in the wilderness, this represented a significant comeback for Hopper, and his work was honoured by festivals and critics' circles around the world (though the good people at the Academy preferred to bestow a Best Supporting Actor nomination on his far more heart-warming performance in the period basketball movie, Hoosiers).

The Academy couldn't ignore Lynch, however, and he was given his second Best Director nomination. Film-lovers the world over breathed a sigh of relief - finally, in a time dominated by such eyesores as Top Gun and Flashdance, here was a great film made by a great director, we thought.

But watching Blue Velvet again two decades on, itís clear we were only half right. The truth is, Blue Velvet isn't perfect. Yes, it's compelling and exciting, and were it not for Raging Bull and GoodFellas at either end of the decade you could make a case for it being the best American film of the 1980s.

You can watch it now and, alongside terrific stuff from Hopper, MacLachlan and Laura Dern, marvel at Isabella Rossellini's heartbreaking femme fatale, or drink in the heady cocktail of cinematography and production design.

The problem with Blue Velvet is David Lynch or, more specifically, the fact that David Lynch went on to do better work. Twin Peaks is a more inventive subversion of small-town Americana, and in Leland Palmer possesses a villain more threatening than Frank since he hides his own corruption, rather than glorying in it.

If Frank walked into a bar you'd walk - or run - out; if Leland Palmer asked you to pass the beer nuts, you'd probably strike up a conversation with him. The good citizens of Lumberton only get into trouble by straying into the wrong neighbourhood, getting mixed up with the wrong kind of people; in Twin Peaks - and this is a far more chilling notion - evil lurks in your home, your family.

As for the other Lynchian chords first struck in Blue Velvet - sexual obsession, ideas of identity, electrifying musical numbers - these would all resurface to more satisfying effect in his masterpiece, Mulholland Dr..

Having said all that, you should still own Blue Velvet on DVD (and the images are beautifully presented on this slick disc), but maybe not because it's the definitive David Lynch movie; instead, think of it as the best Hitchcock movie Alfred himself never made.

Many Hitchcockian elements are present and correct: the lush, Bernard Herrmann-esque score Angelo Badalamenti provides over the opening credits, the MacGuffin of the severed ear, the small-town milieu lifted from Shadow Of A Doubt. The curious, voyeuristic hero comes straight out of Rear Window, only to take a shift into Vertigo territory when Jeffrey becomes sexually obsessed with Dorothy Valens.

When Sandy looks across the table in the diner and says to Jeffrey, "I can't figure out if you're a detective or a pervert," she is basically articulating the question that underscored Hitchcock's finest cinematic hours.