With its oppressive small-town setting, intense central relationship and serial-killer trimmings, you could be forgiven for expecting Beast to be yet another cinematic remix of the Charles Starkweather/Caril Ann Fugate spree: a Jersey Kalifornia, or Badlands in the Channel Islands. Yet, while that connection’s undeniable (tonally and visually, it’s closest to Terrence Malick’s bucolic debut), writer-director Michael Pearce’s first feature has a distinct heart and identity, rooted in his own upbringing on the island and filtered through the legacy of Jersey’s real-life ‘Beast’, ’60s serial sex offender Edward Paisnel.

Beast’s focus is less on a small, closed-minded community under siege by a murderous stalker than it is on one young woman besieged by her own closed-minded family. It is a thriller tightly bounded around main character Moll’s (Buckley) point of view. Thanks to one violent mistake during her childhood, Moll hasn’t been allowed the normal life her siblings enjoy, and has been reduced to little more than a live-in servant by her psychologically abusive mother (James).

Buckley gives a complex, naturalistic performance.

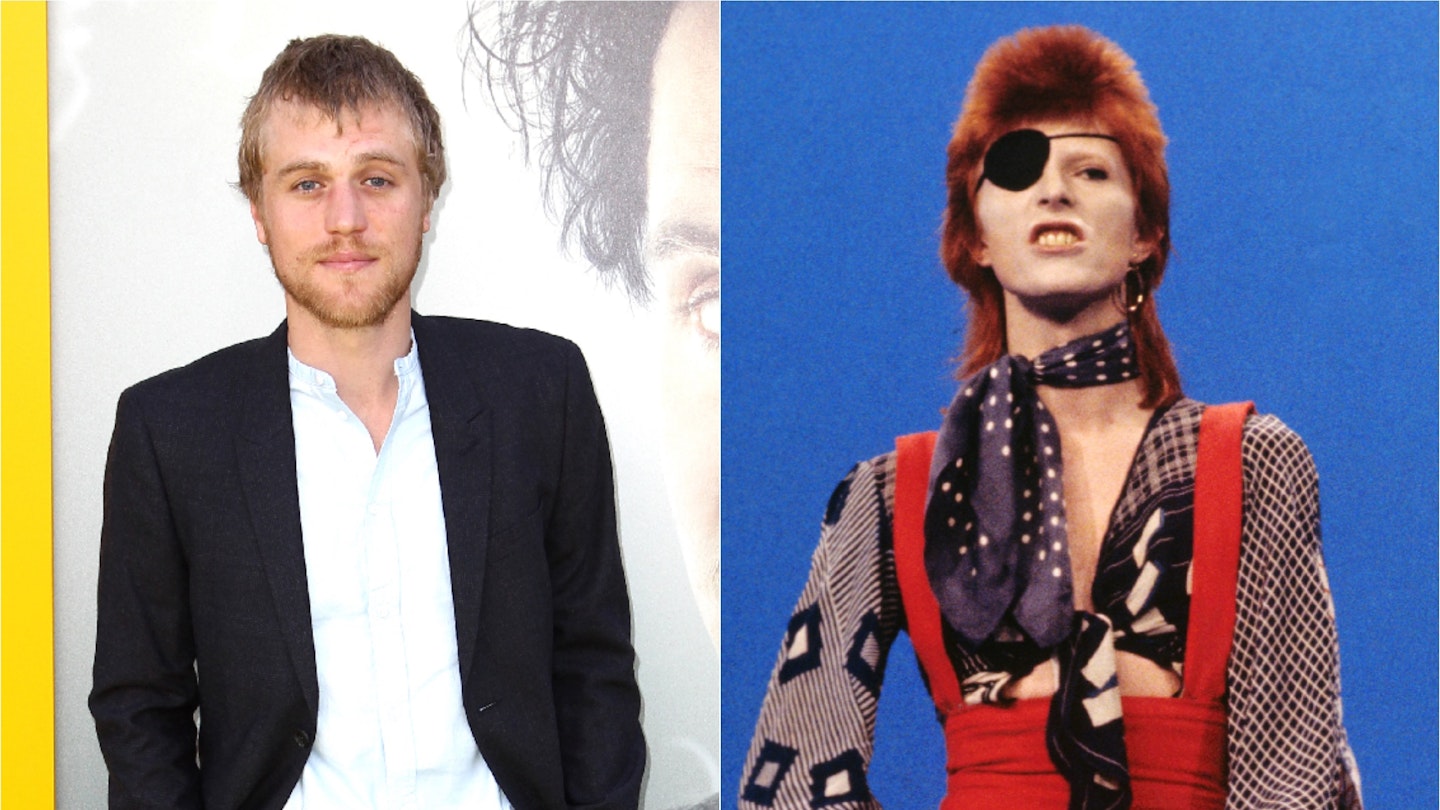

The film couldn’t have worked without a strong lead actor, and Pearce certainly found that in Jessie Buckley. As Moll, she crafts a devastating portrait of repressed expression, existential frustration and dangerously cathartic venting. Her faked birthday-party smiles are almost as disturbing as the primal scream she hurls at a pair of local bully-boys, who later in the story attempt to accost her outside a funeral and are sent into freaked-out retreat. It’s a complex, naturalistic performance which should, by rights, mark the start of a long and impressive career.

Moll’s own internal journey is so firmly the spine of the narrative, it makes her relationship with handsome oddball Pascal (Flynn) feel like a sideshow. But in a good way. This is not a story about a shrinking violet being manipulated by a charismatic monster who drives her to the dark side. It is about how Moll’s own unleashed passions empower her to confront all the bullies in her life, from her politely brutal mother, to her snide sister, to the local copper who fancies her (as long as she remains insipidly pliant). She does go to the dark side, but she’s very much driving herself there — on a journey which begins with faking an alibi for Pascal for the night of the most recent murder.

It’s a journey rendered all the more unsettling by Pearce’s incongruously sun-gilded visuals, which make the setting feel more like Antonioni’s glowing Mediterranean than an island in the English Channel. Like the British-but-not-British Jersey itself, Pearce’s film feels located in the overlap between different realms: both domestic and wild, mundane and necromantic. This gives a fairy-tale-ish edge to Beast: one where the lines between Big Bad Wolf and Little Red Riding Hood become blurred, and a happy ending is by no means assured.