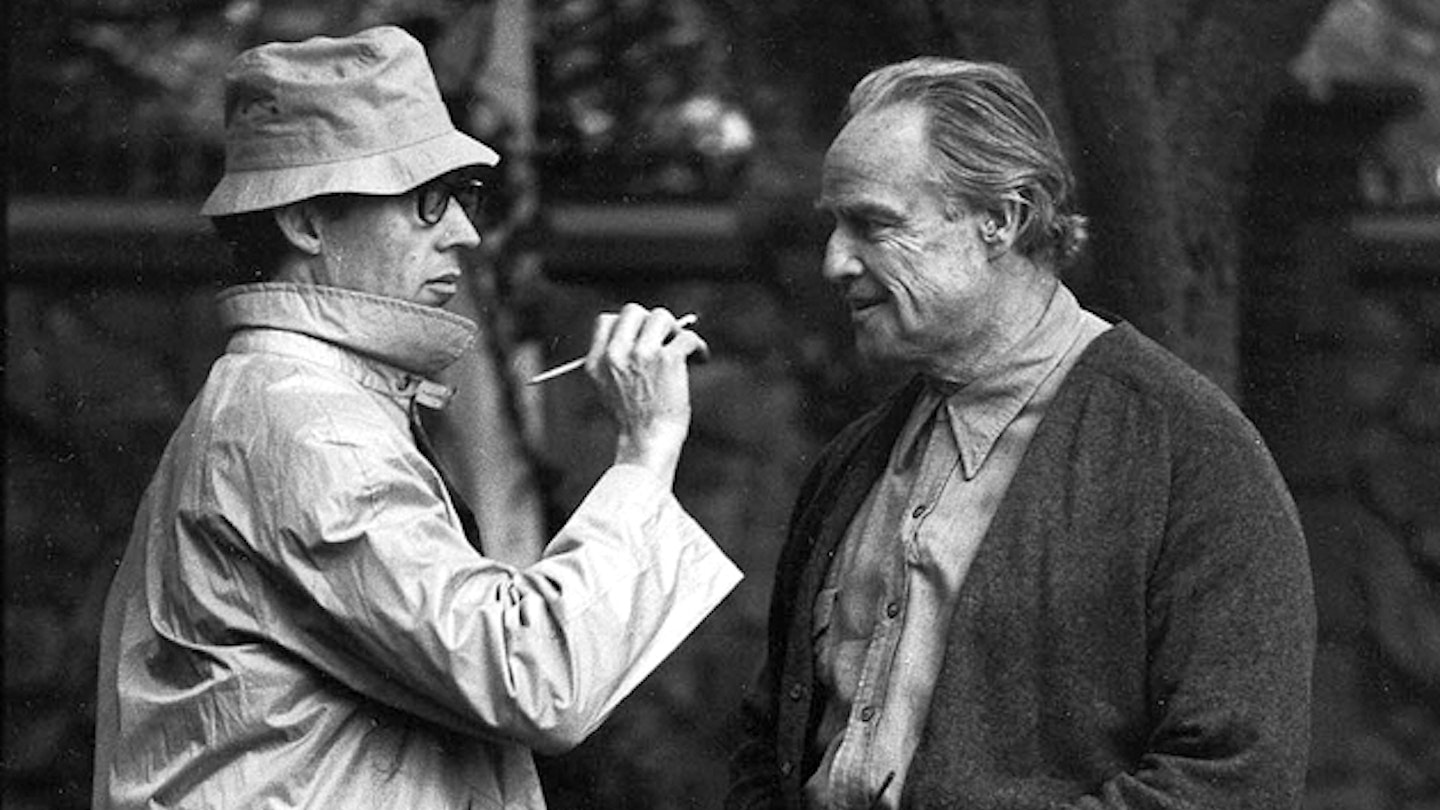

Few historical, Oscar washed epics have as fully grasped the intricacies of man’s capacity to destroy himself as Peter Shaffer’s adaptation of his own stageplay. Hence, Milos Forman’s extraordinarily sumptuous, witty, dark, moving and majestic movie has a texture very much its own, a shadowy intimacy that transcends even the scope and splendour. In a mid-‘80s governed by bombastic, inch-deep action-comedies, this film stood, head and shoulders, above the masses, the masterpiece of its time. To this day, it remains up in the Gods.

Akin to Shakespeare with his turmolic spurts of history, it is the characters who bite deep into our hearts. As Mozart, Tom Hulce, jabbers and warbles like a lunatic, a bumptious, unpleasant, self-centred man blessed with a blazing talent, a “diction from God”. He looks as if he is fit to burst, the burden of these angelic voices too much for his meagre spirit to bare. Forman craftily invited his actors to retain their American accents, liberating the film from the rigid confines of RSC eloquence and opening it up for audiences. There is something punk rock about Mozart’s giddy excess, and echoes of Hollywood’s own bratty talents.

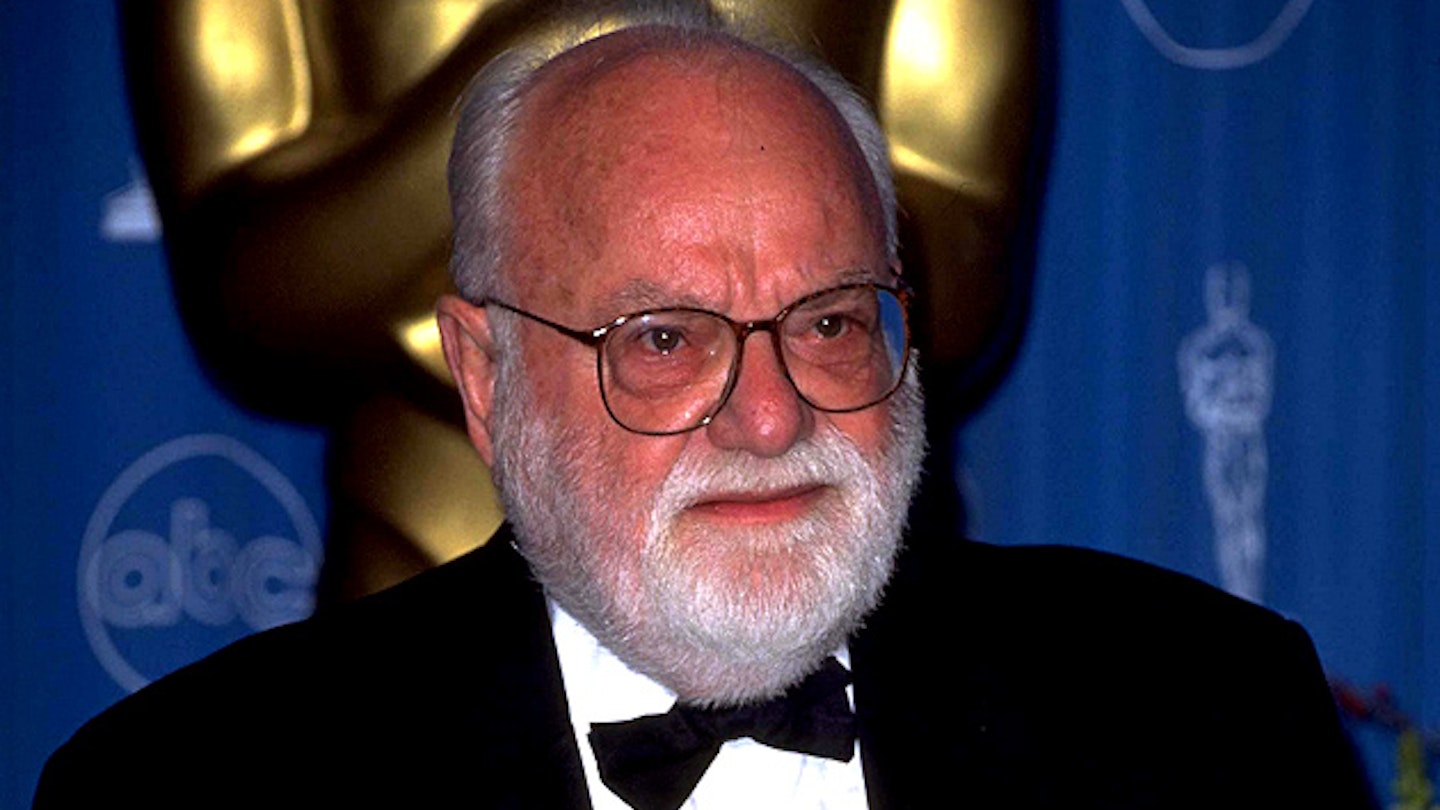

Yet, the film’s dark heart, its poise and class, all stem from his less-talented rival Salieri. Here is a man consumed by envy and a furious religious piety demanding that surely, he, the devoted disciple, should be able to access such dizzying musical creations. For it is he alone, beyond even Mozart himself, who recognises the true genius of those creations, a conflict that will drive him to a moral dementia – to destroy a beauty he adores. As required, F. Murray Abraham gives the performance of a lifetime: brooding, soul-deep, an Iago of seething passion, who always keeps the audience close, intimate to his plans.

The film, so magnificent and ornate, is posing very human conflicts on a grand scale: self-aware mediocrity versus blind talent, liberated creativity versus the establishment. Shaffer, trimming the over-explanatory aspects of his play, fills the film with very modern preoccupations without ever breaking the spell: homoeroticism, ego, creative rivalry, the nature of identity and evil all bubbling and boiling to the surface.

A longer “director’s cut” adds twenty minutes, solidifying some of the backstories and adding a few grim afterthoughts, but slows the natural pace too much, drying out the story. These are relatively minor grumbles, whichever cut you view, Forman’s period piece is worth ever second it demands of you. The music’s pretty good, too.