Platforms: PS5, PC, Xbox

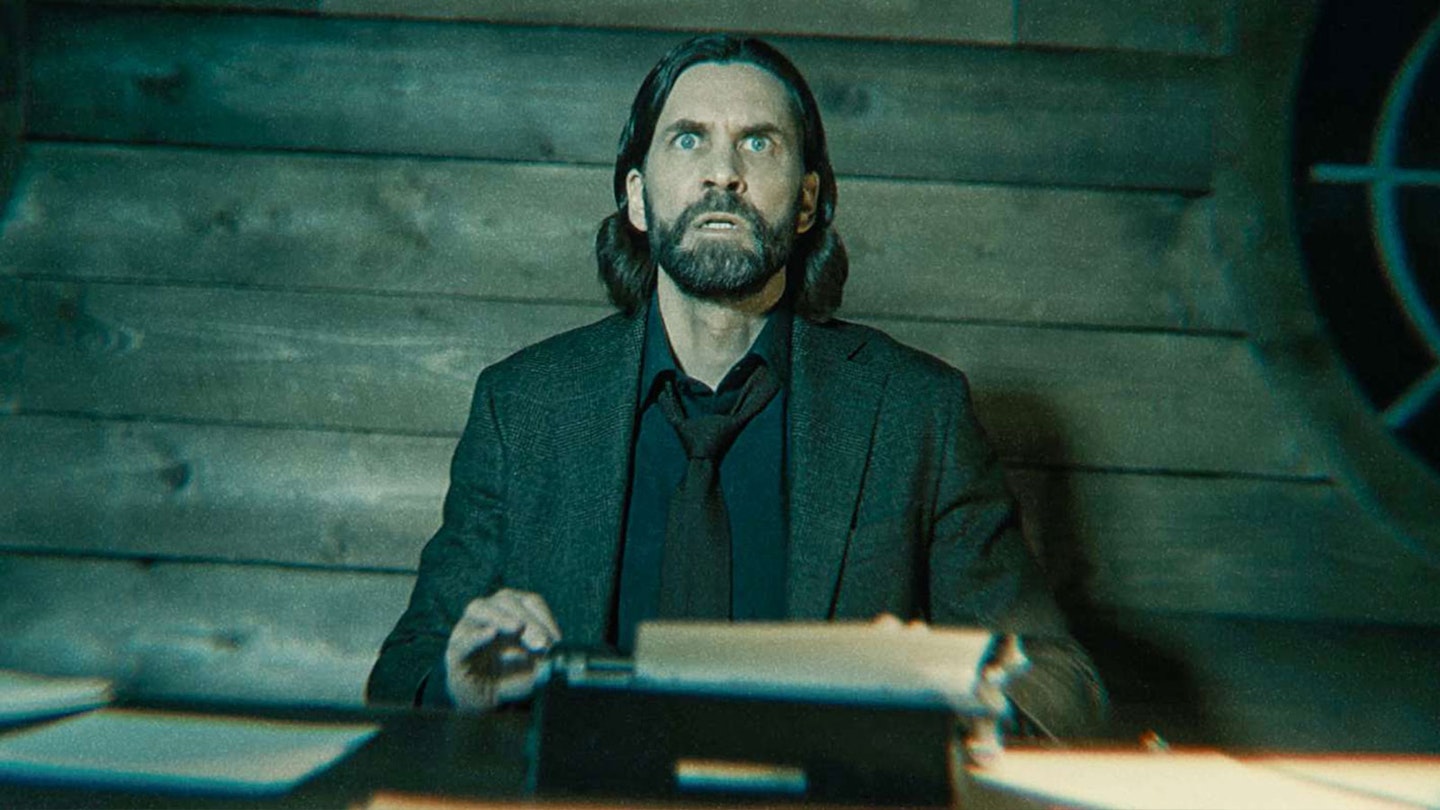

In one of Remedy Entertainment’s earliest video-games, the neo-noir action Max Payne, a scowling image of creative director and writer Sam Lake’s face was used as the eponymous hard-boiled cop. Alan Wake II feels, at times, like the giddy end-point of this decision. The game capitalises threefold on that running in-joke, with Lake now the face of a detective named Alex Casey as well as his curious doppelgänger and even a version of Lake himself. But it never feels self-aggrandising. As well as being funny, it even becomes thematically important, that one shared face spiralling into a wealth of great character moments. It’s but one demonstration of the wonderful, beguiling meta-fiction of this sequel to 2010’s Alan Wake, with exciting connections to Remedy's 2019 game Control: inheriting some of the latter’s visual motifs (giant title treatments, live-action footage) and some of the characters.

Alan Wake II follows two protagonists, in parallel chapters that you can play in any order. One thread follows FBI agent Saga Anderson as she investigates a series of murders in Bright Falls, the returning location from the previous game. Those killings take Saga down a strange rabbit hole, as she stumbles across possessed people called ‘Taken’, and townsfolk who suddenly treat her like she’s lived there her entire life. The other thread follows Alan Wake himself, an author who, in the previous game, discovered that his fiction was becoming real, and that his writing could change reality. He’s now trapped in a parallel nightmare dimension known as the Dark Place, here appearing as a rain-slicked version of New York, emblematic of the noir fiction that the in-game author Alan made his name on.

The dense, Twin Peaks and Stephen King-flavoured narrative turns the very constraints of genre into something working against the characters, Saga and Wake both bristling against the archetypal roles they’re being made to fulfil. The cast is magnetic in portraying how the Dark Place has fragmented their very beings, showing multiple sides of themselves: the storytelling clichés that we see in the Dark Place, the more nuanced characters we meet in the real world, and where they overlap.

They feel trapped, and that oppressiveness bleeds through to combat. The action is incredibly deliberate, and sometimes punishing, a balance of precision aiming, dodging and strategic retreat. It carries forward the conceit of the first game — enemies are shrouded in a supernatural darkness, you use sources of light, mainly a torch, to burn it away and make them vulnerable to gunfire. Encounters are tense, checkpoints are sparse, characters are slow, the weapons feel weighty and unpredictable and ammo can be scarce. Compared to the first game, this is more survival horror — a very natural shift in direction, like it was always meant to be. This isn’t to diminish how fun it is, especially when Lake’s goofy sense of humour pokes through, in bizarre environments (like a coffee-themed theme park) and outrageous set-pieces (there is more than one musical sequence).

A frequently breathtaking work of mixed-media storytelling.

Outside of fighting for your life (some boss fights are surprisingly tough), the most striking element is how this time around the story itself is a puzzle, the player taking part in piecing it together, detective-style. Instead of a quest list or objective screen, you haveSaga’s 'Mind Place’ (apparently different from a ‘Mind Palace’) and Alan Wake’s extra-dimensional ‘Writer’s Room’, both reachable with the press of a button. These are interactive menus that act as a navigable space, a pleasingly tactile way of sifting through the game’s lore and the story’s various twists. As Saga, you piece quests together on a case board, compiling evidence. In Wake’s chapters, it’s a ‘Plot Board’, where you change pieces of a scene to solve puzzles, as editing a scene edits the environment around you. It feels appropriately ritualistic — sequences where Saga profiles people seem more like communing with the dead than psychological analysis. It’s all aided by slick presentation — with an instantaneous switch between the real world and these locations, it’s striking gamification of the mental processes that we could only see passively in the first game.

The world itself also feels like a puzzle: its levels are all strange liminal spaces, the world subtly shifting to throw you off balance. Furthering that uncanny atmosphere is its transitions between its incredibly detailed and expressive in-game animation and live-action performance, often overlapping the two. Like in Control, Alan Wake II interpolates video footage of real actors, superimposed over the game environment. At a time where cinematic games rule the AAA space, Alan Wake II stands out as one with a genuinelyexperimental visual ethos. Appropriately for a game about fighting the darkness with light sources, it leans on areas that turn single light-sources into its own kind of horror: it feels like there’s something lurking around every corner, and the cold neon lights of Alan’s nightmare NYC stand out all the more, contrasted with the warm pine forests and mountains (and quirky towns) of Bright Falls. Alan Wake II is technically impressive, too, particularly in the immediacy when switching to the Writer’s Room and Mind Place, as well as the moments where Wake rearranges the world around him. Even in performance mode (which loses some visual definition in favour of a solid 60fps), its gorgeous production design makes for some of the prettiest imagery of the year, spectacular to behold even at its most unnerving.

Alan Wake II is a frequently breathtaking work of mixed-media storytelling, not just a game that aspires to become cinematic or televisual or even literary, but one that asks how it might integrate those different artistic languages, how gameplay can experiment with and transform the storytelling experience, and how environmental design and (often literal) gameplay loops can reflect a character study. If it’s all going to be as ambitious as this, we hope the Remedy-verse keeps on expanding.