After their very productive relationship on Gallipoli, director Peter Weir and actor Mel Gibson reunited for this high-minded and atmospheric study of a reporter finding what he needs, a story, and what he hadn’t foreseen, his own soul. With its echoes of Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, the script is inevitably preachy and Weir’s camera glowers over the injustices of President Sukarno’s failing regime in late 1965, but the performances are strong and the drama gripping.

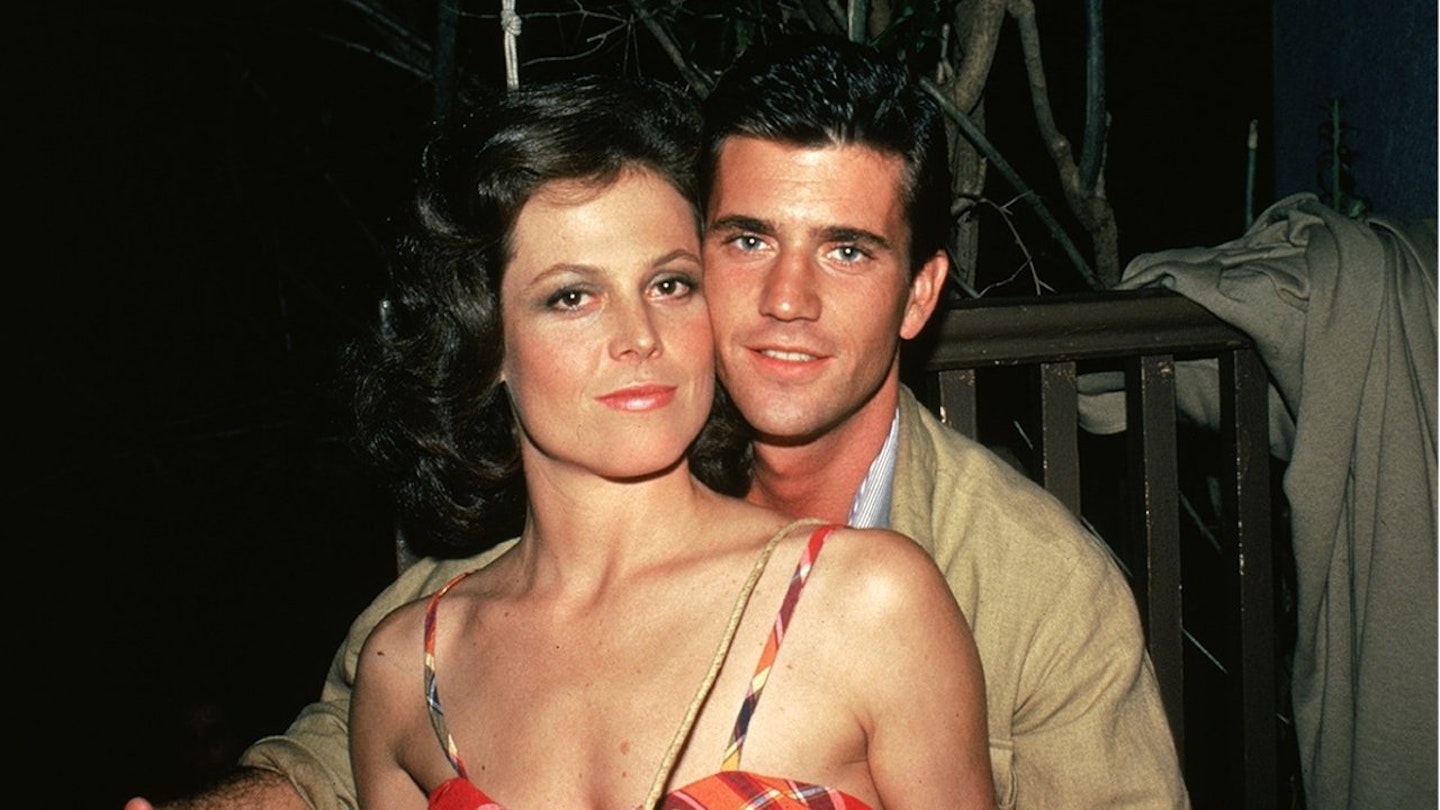

Gibson gives urgent life to this Aussie correspondent determined to make his mark, also embarking on a torrid affair with Sigourney Weaver’s frosty diplomat. His pursuit of a story is at first a pursuit of personal glory as he manipulates those around him, but the country will come to wake him up. All about him the sweaty tangle of a nation in turmoil is pungently brought to life by Weir who shot in the Philippines. Yet, the centre of the film, its conscience and poetic voice, is Linda Hunt’s half-Chinese dwarf photographer who freely quotes from Tolstoy and her people’s need for some kind of salvation. It’s a captivating, dynamic and unusual performance that deservedly won Hunt an Oscar working, as she was, even against gender.

Weir’s contentions about the events that fermented in Indonesia in the mid-‘60s were called into question upon the film’s release, and he had argued furiously with Christopher Koch upon whose novel the film was based, fixing on the now discounted contention that the CIA were behind the coup. But controversy aside, the film has weathered well, especially in Gibson’s moving relationship with Hunt, the emergence of a man who has contended with politics and morality, but was only now engaging with the reality of people’s lives. The Killing Fields may have made similar points about charging front-line journalists with nobility to greater acclaim, but this remains a powerful evocation of a nation’s rage.