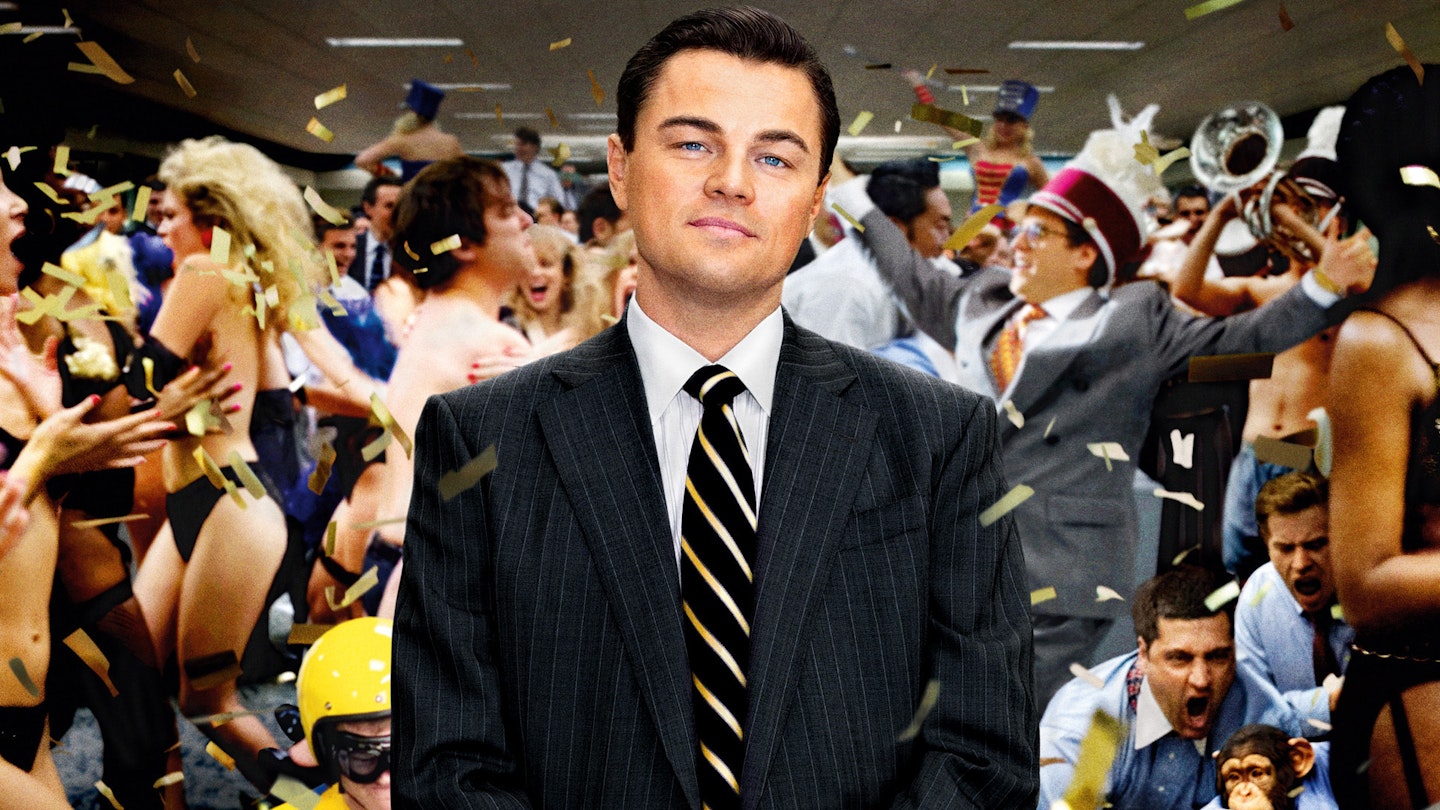

The Wolf Of Wall Street is the first Martin Scorsese film in a good while that feels as though, in a few years' time, it will join Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and GoodFellas in the canon. It arrives as Casino did with a lot of fanfare, but doesn’t quite deliver what many of us were expecting, and for some, it’s a film that might take a little bit of getting used to. Though it starts with a dash of the usual visual pyrotechnics, the tone is much straighter than we’ve come to expect, with longer, more intimate scenes and a much greater emphasis on script. But the oddest thing of all about The Wolf Of Wall Street is also the most unusual for a Scorsese film: it is incredibly, incredibly funny.

That the comedy is so effortless is another striking thing about Scorsese’s 23rd feature, since it is his first film since 1999’s Bringing Out The Dead — also rich in black humour — that doesn’t seem to be made to an Academy agenda. With The Wolf Of Wall Street, the director’s early energy comes flooding back. It’s big but not Gangs-Of-New-York epic, and it finally seems as though Scorsese is once again interrogating the material, finding the substance of the piece. On paper, the story of Jordan Belfort seems tailor-made for him — it is a criminal’s survivor story, with Wall Street as the Cosa Nostra of our times — but this isn’t GoodFellas with stocks and shares; it is a film with one eye on us, the audience. Like the very best of Scorsese’s work, it involves an antihero who pushes us to the very limits of our sympathy — Jake LaMotta, Rupert Pupkin, Travis Bickle — but Jordan Belfort might be the worst of the bunch. And it is the genius of the film, not only in Scorsese’s direction but in Leonardo DiCaprio’s untouchable performance, that three hours in the company of a man who exploits the poor and wallows in obscene wealth simply whizzes by.

It could just be that, for once, Scorsese has been looking around him. His Personal Journey series of docs famously stop at the point when he started making movies himself, so he doesn’t have to judge his peers, but The Wolf Of Wall Street has the air of a filmmaker looking round for ideas. Here, one can detect not only a little hint of his godchildren — Tarantino and P. T. Anderson spring to mind — but the sense that this is determined not to be a typical Scorsese movie. His camera stays longer than it used to, and though the trailer suggests lots of jittery rap, the needle-drops are shorter and less foregrounded than usual. In fact, there’s very little modern music, with Howlin’ Wolf’s pounding Smokestack Lightning accompanying much of the mayhem.

It also feels that Scorsese’s collaboration with DiCaprio has actually broached the levels of his early work with Robert De Niro. The Wolf Of Wall Street really feels organic in that way; whereas in Gangs Of New York and The Aviator DiCaprio seemed a little formal and staid, here he is completely off the chain. One might even wonder if the idea for a film like this was fomenting in the back of Scorsese’s brain as he filmed Jerry Lewis in The King Of Comedy — strip away the sex and drugs (God forbid, since that’s half the movie) and you have The Nutty Professor with the roles reversed. Jordan Belfort actually is the cool, smart, sophisticated Buddy Love, but with the aid of serious chemicals he transforms himself into the gibbering Dr. Julius Kelp.

DiCaprio is undoubtedly at his best here, completely in charge of his range and versatility. The slapstick elements are the most obvious proof of this — the scene in which he attempts to drive his car on vintage Quaaludes is just jaw-dropping — but it’s hard to think of another actor who could pull that off and then segue so seamlessly back into Belfort’s public persona. By the end of the film, Belfort has transformed from huckster to evangelist, and it is his messiah complex that brings about his downfall. Nevertheless, we buy into that too, and this is what the film does best: though we are often reminded that Belfort is a love rat, a drug addict and a con man who preys on the poor, these things rarely seem to matter.

This might well be because Scorsese has one eye on the backdrop, and around DiCaprio he has assembled one of his best ensembles ever. Leading the pack we have Jonah Hill as Belfort’s sidekick Donnie Azoff, a hedonistic putz with bizarre white teeth who gets some of the biggest and broadest laughs without ever straying into caricature. Matthew McConaughey comes and goes, but his presence is indelible, being not only hysterical but inspiring Belfort to adopt the business practices and lifestyle that will lead him to jail. Finally, though there isn’t very much for any woman to do in this movie, it’s worth mentioning that Margot Robbie is excellent as Belfort’s wife Naomi, slowly becoming the film’s conscience and emotional compass.

As regards the latter, the film plays fast and loose with its morality, setting up Belfort as the narrator of his own story to such an extent that when he crosses the line, as he so often does, Scorsese doesn’t comment. Instead, he shoves our noses in the huge pile of pharmaceutical cocaine that was, for a few years, Belfort’s life. And we inhale so deeply that it is only afterwards, when the comedown sets in, that we start to reflect on Jordan Belfort, what he did to make his money and what he did when he got it. It’s hardly a spoiler to say that Belfort gained a quasi-respectable fame through his notoriety, but The Wolf Of Wall Street joins a short sub-category of Scorsese films (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, The King Of Comedy) in which troubled men become media celebrities as a direct result of their crimes and misdemeanours.

It doesn’t take an MA in film studies to see what’s going on here, and that’s what makes The Wolf Of Wall Street so invigorating. Scorsese isn’t wagging the finger at Wall Street, he’s wagging it at us, offering a mirror of the fucked-up world we’re living in. As Mark Twain once said, “Humour is tragedy plus time,” and as warnings from history go, it doesn’t get more timely than this.