It was over a decade since cinema had witnessed a genuine gangster. The imposition of the Production Code in 1934 had just about put paid to the violin case-carrying hood of the age, while nothing as unpatriotic as crime was allowed near American screens during World War II.

Increasingly affluent audiences didn't want to be reminded of the prohibition-depression era and, consequently, the very nature of movie crime changed. Instead of being career criminals with a killing complex and delusions of grandeur, the anti-heroes of the film noir boom were essentially decent saps who were led astray by their adverse post-war circumstances or tempted into indiscretion by a smouldering femme fatale.

So James Cagney was definitely bucking a trend when he decided to return to the gangster flick in mid-1949. Swallowing his pride, after the disappointing performance of Cagney Productions, he re-signed to Warner Brothers the studio from which he had parted six years earlier and allowed himself to be talked into Raoul Walsh's White Heat. However, this wasn't quite the capitulation it seemed. Such was Cagney's determination to shake his persona that since The Roaring Twenties (1939) he had refused to even read crime scripts. But, his desperate need for a hit after a string of misfires was equally pressing and so he agreed to work with the man who had so successfully remoulded Humphrey Bogart's screen image in High Sierra (1941).

Walsh planned to move Cagney out of his overly familiar tenements and into a rural setting more akin to a modern-day Western than an old-fashioned mob movie. Moreover, he was happy to acquiesce in Cagney's insistence on placing an emphasis on recent advances in scientific detection to ensure that the picture carried a "crime does not pay" message. But screenwriters Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts were far more interested in the psychology of the psychotic. Thus, they sought to depict Cody Jarrett as a megalomaniac doomed by his own failings to destruction.

The inspiration for their story was Ma Barker, although they distilled the violent malevolence of her four sons into a single figure. As played by Margaret Wycherly, it's easy to see how such a mother could have engendered Cody's cynical, calculated approach to crime (especially bearing in mind the implied oedipal nature of their relationship). But it's also intimated that Jarrett was born with the mental fragility that so frequently tipped him over the edge and, thus, made him marginally less morally responsible for his actions. Some critics have claimed he's an epileptic. But, whatever the cause of his mania, he is, like Hans Beckert in M, a victim of destiny.

The ferocity of Ma's hold over Jarrett is most clearly evident in the prison mess-hall sequence. Having learned of her death, he hurtles down the table lashing out at guards and cons alike in frenzied distress. The scene is rendered all the more shockingly realistic by the fact that not only did Cagney reproduce the pitiful screaming he remembered from his father's drinking bouts, but Walsh didn't tell the 300 or so extras what was going to happen, hence the genuine bewilderment in their expressions. The scene deeply disturbed Cagney, however, and after a preview screening he refused to watch the film ever again.

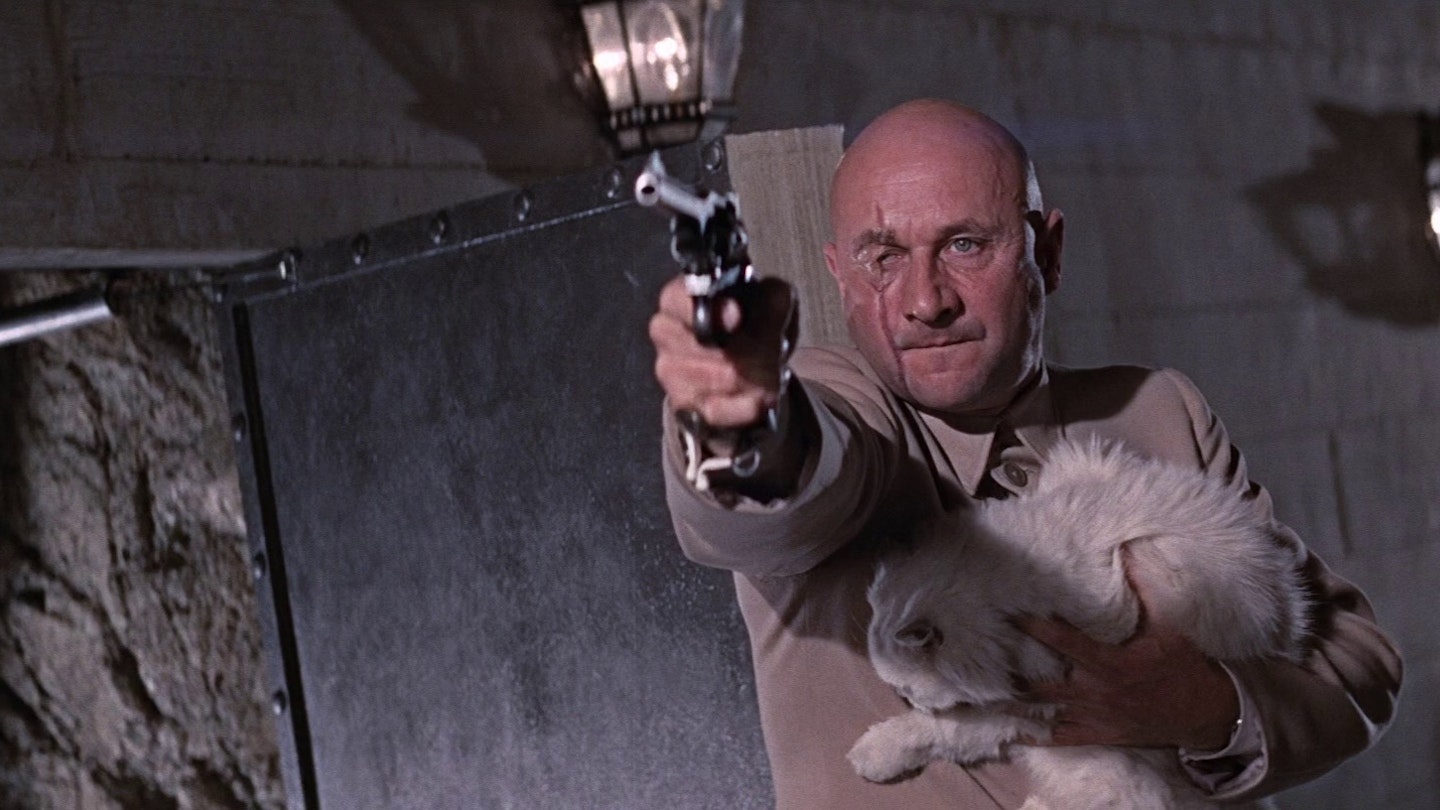

Yet for all the violence and anguish, there's also a dark undercurrent of comedy. It's almost as if Cagney were parodying his previous incarnations. Just as he pushed a grapefruit into Mae Clarke's face in The Public Enemy (1931), here he knocks Virginia Mayo off a chair as she shows off her new fur. Similarly, he also has a number of callous one-liners, none more heartless than the one which follows his silencing of a stool-pigeon's muffled cries as he riddles a car boot with lead "Oh, stuffy, huh? I'll give you a little air." With its 13 slayings, White Heat was hot stuff for 1949, prompting Bosley Crowther of the New York Times to declare it was "A cruelly vicious film", and that "its impact upon the emotions of the unstable or impressionable is incalculable". He was also prepared to concede that, "Mr. Cagney achieves the fascination of a brilliant bullfighter at work, deftly engaging in the business of doing violence with economy and grace".

Bridging the gap between the rise-and-fall pictures of the 1930s and the syndicate dramas that would dominate the 1950s, the film ends with a symbolic mushroom cloud, as Cody blows up a gas tank rather than be taken alive. It was also a token gesture on Cagney's behalf, as rarely again would he be such a potent screen force as this.