Some movies are best treated as cinematic souvenirs. Like tacky snowglobes brought back from school trips to Switzerland, or bronze Eiffel Towers with dangerously sharp edges that linger on mantelpieces the world over, worthless and unloved, until they catch someone’s eye and remind them of the vanished age from which they came.

Top Gun is such a film. Defending it as a work of art would be either brave or reckless. As an historical artifact, though, it’s peerless. Like it or not, if you want to know what pop-film was like in the mid-’80s, there’s no better example than this chrome-burnished, distilled-to-within-an-inch-of-its-life, high-gloss tale of testosterone-charged flyboys and their big, fast planes.

It was, of course, an outrageous hit, and Top Gun contains most of the pan-audience pleasing features that An Officer And A Gentleman (another Simpson / Bruckheimer film, and template for this one) had boasted: a military setting; exciting training sequences; good-looking male lead with a spiffy uniform; a love story; and a competitive element. The formula had worked before, and Simpson was betting it would work again.

Top Gun is not so much a movie in the conventional sense as an escalating series of masterfully crafted adverts: motorcycles, aircraft carriers, pectorals and planes all look as if they’ve been shot for a particularly luminous beer campaign (and while this style looks tired now, it was a revelation at the time). No wonder the American Navy not only provided millions of dollars’ worth of hardware gratis, but also stationed recruiting officers outside suburban multiplexes to catch testosterone-addled adolescents still promisingly drenched in cinematic piss and vinegar.

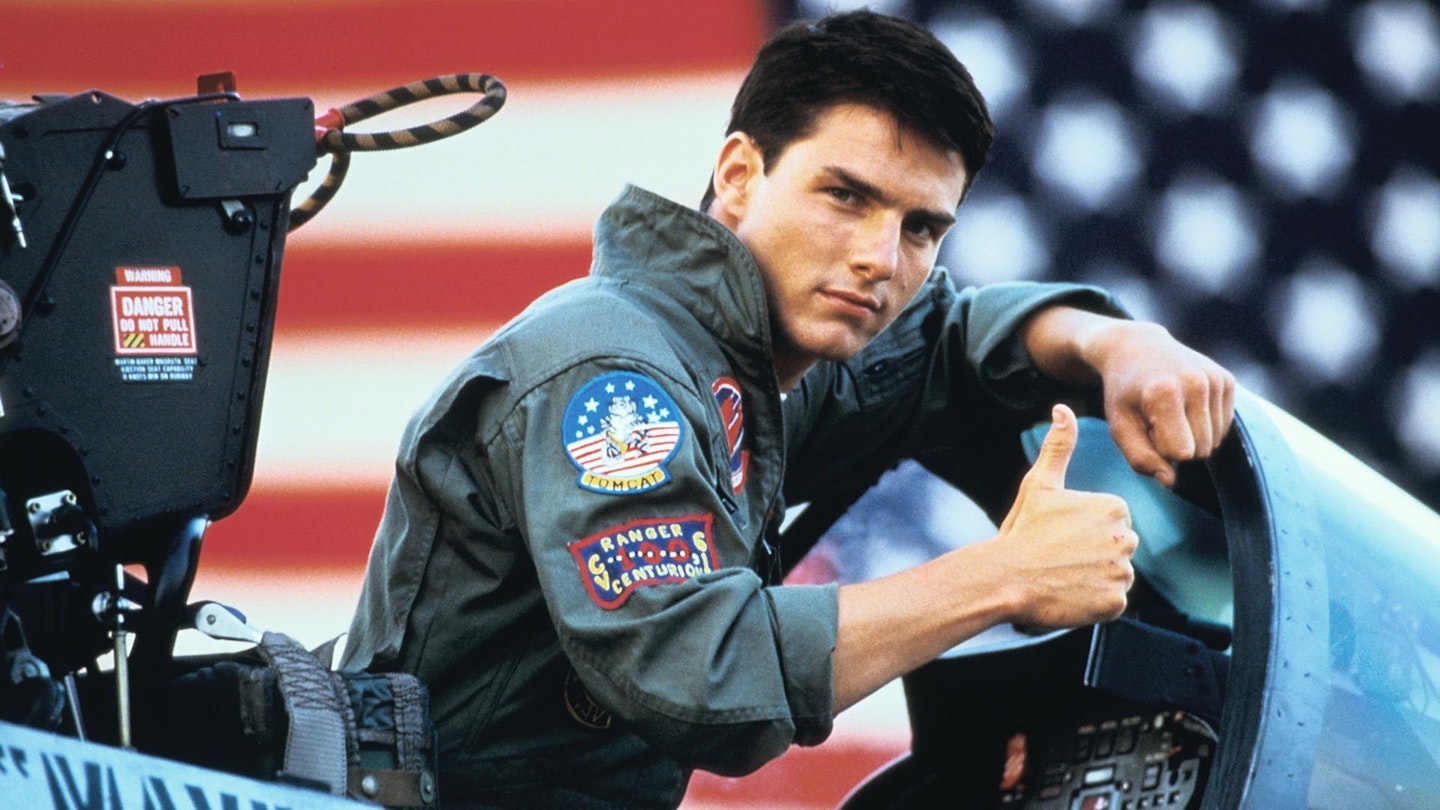

For their leading man, Simpson and Bruckheimer had their eye on a promising kid called Tom Cruise. Cruise had been bubbling under as a potential breakthrough star with Risky Business and All The Right Moves. Having just finished filming the mildly troubled Legend - directed by Tony’s brother - Cruise (hell, let’s call him The Cruiser, this is the ‘80s) was nervous about Top Gun; even that early in his career he was smart enough to see that the movie had the potential to be, as he put it, ìjust Flashdance in the skyî. But Simpson was determined, finally coughing up what would in retrospect be a very reasonable $1 million (Cruise’s first) for the 24 year-old. And Simpson was also determined to get his money’s worth. When an on-set military adviser pointed out that the majority of professional discourse in navy flight schools did not happen in locker rooms, nor with the flyers clad only in their underwear, Simpson was unimpressed. “I have just paid a million dollars for that kid,” he impatiently announced, “and I need to see some flesh.”

And so to the question, “Is it any good?” Well, what can be said with certainty is that with contemporary dreck like Van Helsing and Bad Boys II sloshing around the multiplexes (both movies that Simpson would likely have loathed), ‘80s dreck doesn’t look too bad. The flying sequences remain exciting, there is something approaching a story - even if it is emaciated - and, for good or ill, it inaugurated the Cruise grin, which still beams down from multiplex screens two decades later. Tat, certainly, then. But tat to be treasured.