Coming off the back of four flops, Alfred Hitchcock's yen for a hit prompted him to plump for this readily accessible thriller, in which an unhappily married man meets a sexually repressed psychotic, who suggests they carry out the perfect, undetectable murder by

exchanging victims. In order to ensure a bargain price, Hitch anonymously secured the rights to Patricia Highsmith's novel, which he promptly proceeded to fillet with Whitfield Cook. Guy Haines was transformed from an architect to a tennis player with political

aspirations and instead of standing trial for the murder of Bruno Anthony's father, he is given sufficient conscience to try and warn him. Furthermore, the slim volume of Plato, which Bruno uses to implicate his reluctant partner in crime, is changed to a lighter, inscribed to Guy from his mistress, Anne Morton.

Having failed to interest a number of leading writers, Hitchcock turned his treatment over to Raymond Chandler to work into a screenplay. However, there was instant antipathy between the two, with Hitch being particularly unhappy with the ending, in which a strait-jacketed Bruno is left writhing in an asylum cell. Ultimately, Chandler retained his credit. But much of the shooting script was actually written by the novice scenarist Czenzi Ormonde. Among her contributions was the merry-go-round finale, which was borrowed from Edmund Crispin's pulp novel, The Moving Toyshop (1946). A couple of other set-pieces were also slightly second-hand. The famous tennis gag, in which Bruno sits impassive amidst a crowd intently following a rally, had featured in the Somerset Maugham compendium picture, Quartet (1948), while the symbolic use of a barred gate to imply Guy's culpability for Bruno's crimes was lifted from Robert Siodmak's film noir, The File OnThelma Jordan (1949).

But, if the script could be fixed, the cast couldn't. While he was content with Robert Walker as Bruno, Hitchcock wanted William Holden for Guy and was disappointed to end up with Farley Granger, with whom he'd already had problems on Rope (1948). Furthermore, he found Ruth Roman cold and stiff as Anne, although he cheerfully cast his own daughter, Patricia, as her gauche sister, Barbara.

Pandering to popular expectation, Hitchcock produced a thriller to restore his status as the Master Of Suspense — even though there were gaping holes in the narrative's logic. But he was less concerned with why Guy failed to go to the police after his initial meeting with Bruno or after his wife Miriam's murder or before the death of Bruno's dad.

Instead, he was preoccupied with the thematic contrasts between light and dark, order and chaos, innocence and guilt.

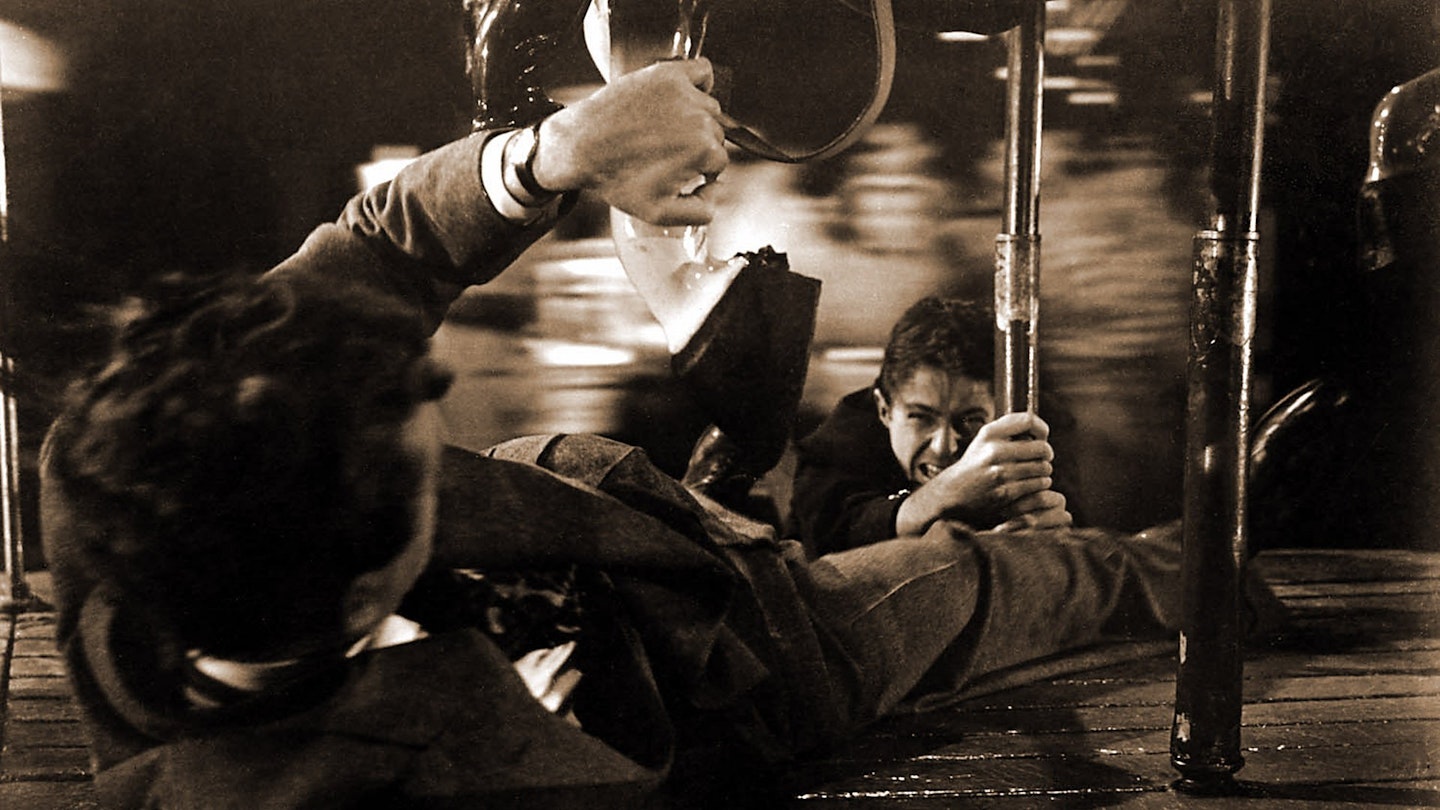

Moreover, he was besotted with images depicting circles, doubles and traverses. Curvilinear imagery had already dominated such early Hitchcock outings as The Ring (1927). But here he litters the screen with round objects, whether it's the records in Miriam's shop, the abundance of clock and watch faces, Guy's racket and tennis balls or the balloon Bruno bursts before he murders Miriam beside the fairground carousel — during which he is hideously magnified (and doubled) in the lenses of her discarded glasses.

The double motif is pursued with equal rigour. There are two tennis matches, two scenes centred on a merry-go-round, two respectable, but domineering and distant, fathers and two assaulted women wearing glasses. There are two old maids fascinated by the mechanics of murder, two sets of private detectives and two rounds of double whiskeys. Even Hitchcock's cameo adhered to the idea: he carried a double-bass case, which he thought resembled his own physique.

Just as the surfeit of annular objects is supposed to convey the vicious circles from which both Guy and Bruno seek to extricate themselves, so the various pairs, in those Production Code days, suggest the homoerotic connection between the prospective killers. Similarly, the recurrent criss-cross patterns also carry symbolic weight — from the shadowy bars that bedeck Bruno on the train and Guy's face on the Washington street to the decussating tennis rackets on Guy's lighter — for, even though he benefits from Miriam's demise, Guy still intends to double-cross Bruno by refusing to carry out his part of the bargain.

Guy may be our hero, but he is a thoroughly resistible character and, thus, seems set to do well in politics. Recalling the lethal charm of Uncle Charlie in Shadow Of A Doubt (1943) and anticipating the Oedipal derangement of Norman Bates in Psycho (1960), Bruno is far more engaging, making the death of Robert Walker (the year after, at 33) all the more tragic.

In conclusion, it's worth noting that the luncheon sequence, in which Bruno asserts that everyone is a potential killer, was excised from the original US print. But, then again, Anne and Guy's climactic train-board meeting with a star-struck clergyman was absent from the British version.