Steve Jobs is thrilling. Which should sound counter-intuitive. Isn’t this a film about a man who made computers? Operatic in scope, breathtakingly articulate, and held firm by a snake-charmer of a central performance, it is, in fact, another ambitious reckoning with a flawed American titan; a sister parable to the Zuckerberg-autopsy The Social Network; an intricate, dazzling, zeitgeist-lassoing Citizen Kane. Or, if you prefer, The West Wing in the tech sphere.

The hook is a backstage drama, Birdman’s twitchy Broadway neuroses neatly divided into three acts, each located just as Jobs (Michael Fassbender) is due to unveil his latest game-changer. In 1984, Cupertino buzzes with anticipation for the launch of the Macintosh, the friendly-faced challenge to the supremacy of the PC. But behind-the-scenes he is assailed by breakdowns of all guises, including a wounded ex (Katherine Waterston) trailing a five year-old daughter (Makenzie Moss) she claims is his. In a stunning rendition of Jobs’ emotional sangfroid, he has constructed an algorithm to prove there is a 28 per cent chance she belongs elsewhere. Then his dead gaze flickers into life as the girl, named Lisa, takes to his new computer.

It’s a repeated pattern. In 1988, an exile, Jobs prepares to launch his ill-fated NeXT system, while plotting revenge and dealing with a Lisa pressing for the attention he lavishes on his computers. By 1998, the prodigal returned, he is about to establish Apple as chief catalyst of our cultural destiny by giving us the iMac. Late on Jobs chases an infuriated Lisa to a rooftop and points to her boxy Walkman. “We’re going to put 500 tunes in your pocket,” he reports, as if that makes things right. The iPod is already cooking in the brain of this man who unerringly grasped the interface between people and objects. It is the connection of people to people that was beyond him.

All of screenwriter Aaron Sorkin’s virtuoso scene-construction and supercharged dialogue, drawn from Walter Isaacson’s biography, electrifies the wilting biopic into grand Shakespearean tragedy. This is living biography, Jobs’ inner-workings not so much psychobabbled as psychobombarded. Jeff Daniels as John Sculley, Apple CEO and great betrayer, repeatedly head-doctors Jobs’ twisted roots. “Why do people like you,” he wonders, “who were adopted, feel like they were rejected instead of selected?” No-one ever talks like this, not even Steve Jobs, but it makes for soaring drama.

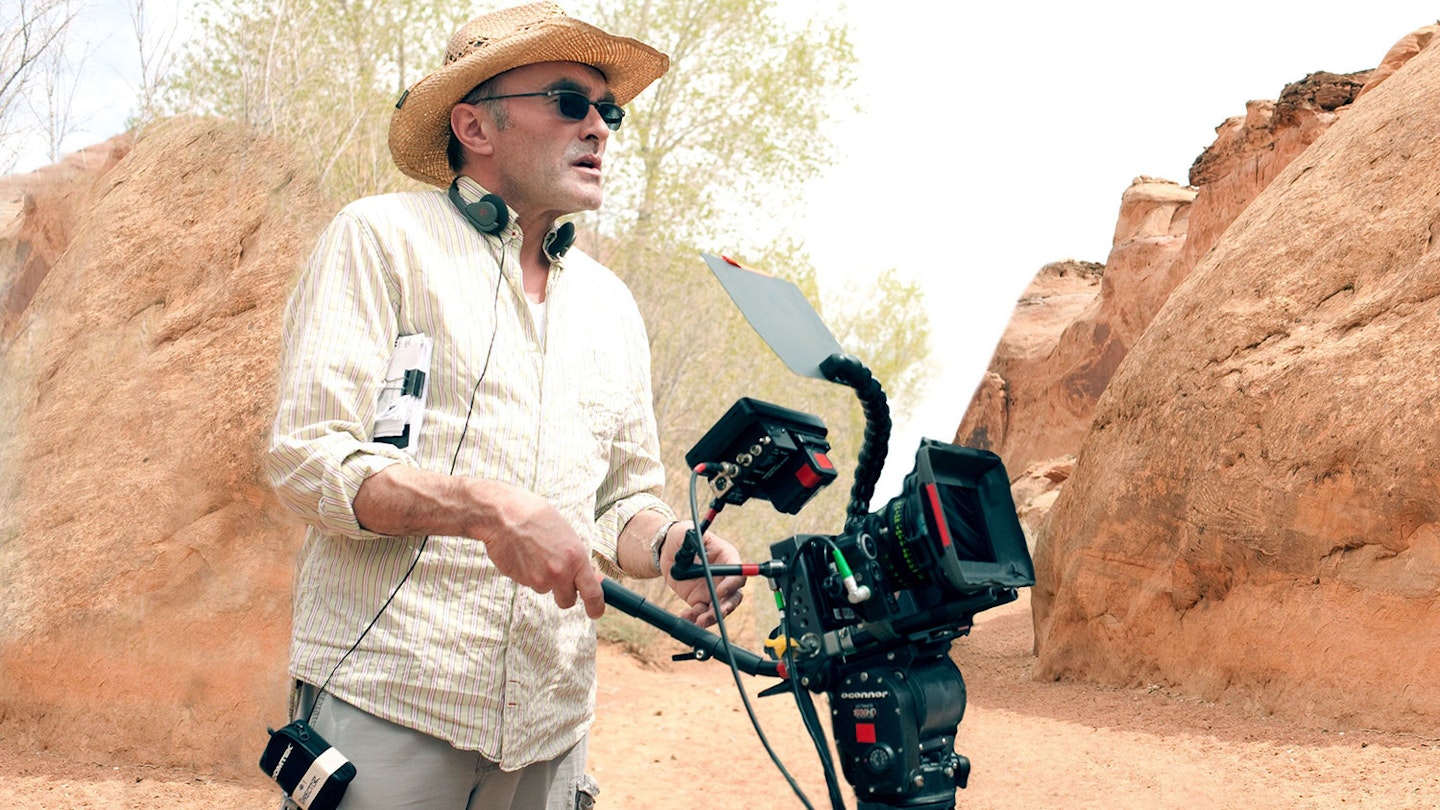

Having Sorkin in full spate doesn’t make it less of a Danny Boyle movie. Only a more mature, focused, theatrical Boyle. He lets the talk surge through long, dynamic takes. His camera roams the networks of backstage corridors, riding the currents of high-anxiety. During a boardroom flashback, as Jobs faces downfall, an apocalyptic deluge cascades down the windows. Each of the three eras is shot in time-specific stock. The electronic score follows suit. Everything configures as metaphor.

There’s not a flat note in the performances, either. How could the actors not thrill to the music of these lines? Kate Winslet exudes steadiness and sanity as marketing-guru Joanna Hoffman, Jobs’ constant confessor. Seth Rogen is a fine Steve Wozniak, Apple’s co-founder whinnying for recognition. “I’m tired of being Ringo,” he implores, Sorkin laying bare an entire relationship in a single line, “when I know I’m John.”

There is an amusing Venn diagram in the magnificent Fassbender playing Jobs between Macbeth and Magneto. Invoking rather than mimicking the nasal accent and stiff gait, he nails the mesmerising zeal and icy cruelty, but defies the film’s search for conclusions. He leaves Jobs fascinatingly elusive, both genius and sociopath. The ultimate closed system. We can see inside, but never know how it works.

.jpg?ar=16%3A9&fit=crop&crop=top&auto=format&w=1440&q=80)