The Thracian slave Spartacus, thought to have been a deserter from the Roman army, was sold to a school for gladiators at Capua but never got to the arena, leading a slave revolt in 73 BC and devastating Southern Italy with an army of former slaves and gladiators. He was defeated in battle in 71 BC by Marcus Crassus, probably dying on the field of combat rather than surviving (as in the movie) to be crucified. Crassus, with Pompey and Julius Caesar, formed the first Triumvirate of Rome, precursor to the Emperorship of the Caesars, but came to a bad end in 53 BC when he was himself killed in a war he had started.

In the film, Crassus (Laurence Olivier) remarks, "This compaign is not done to kill Spartacus, it is to kill the legend of Spartacus." The real rebel was a ruthless plunderer who had 300 captives put to death to avenge the killing of his best friend Crixus (the part played by John Ireland) and once, before a battle, crucified a captured Roman soldier in front of his own men to show them what would happen if they lost to the legions.

The legend of Spartacus stands for resistance to tyranny.

But the legend of Spartacus stands for resistance to tyranny. In the 20th century, a German socialist faction called themselves the Spartacists, and communist Howard Fast's Spartacus depicted the slave revolt in Marxist terms. Another blacklistee, Dalton Trumbo, hewed a screenplay from Fast's novel, relishing the scene in which Crassus delivers straight McCarthyist rhetoric ("The enemies of the state are known, arrests are in progress, the prisons begin to fill. In every city and province, lists of the disloyal have been compiled"). Trumbo stirred in incidents from Arthur Koestler's novel The Gladiators, which might have been a Yul Brynner movie if producer-star Kirk Douglas hadn't made sure his rival project was so much bigger.

Excepting a stint on Marlon Brando's One-Eyed Jacks (1961), which the star ended up directing himself, Spartacus was Stanley Kubrick's only film as a for-hire director. He was brought in when Douglas fell out with the original helmer, Anthony Mann — director of great Westerns in the 1950s, who shot the opening Libyan mine sequence — and never quite got up to speed on the picture. Still, many scenes and ideas in Spartacus are completely Kubrickian: he returned almost obsessively to brutal training regimes that turn men into machines in A Clockwork Orange (1971) and Full Metal Jacket (1987) and staged another huge historical battle in Barry Lyndon (1975). But the director is clearly much happier with Spartacus The Legend and the power struggle between Patrician Crassus and Plebean Gracchus than he is in scenes that try to show Spartacus The Man: pining for peace, loving his wife (Simmons) and palling around with his men.

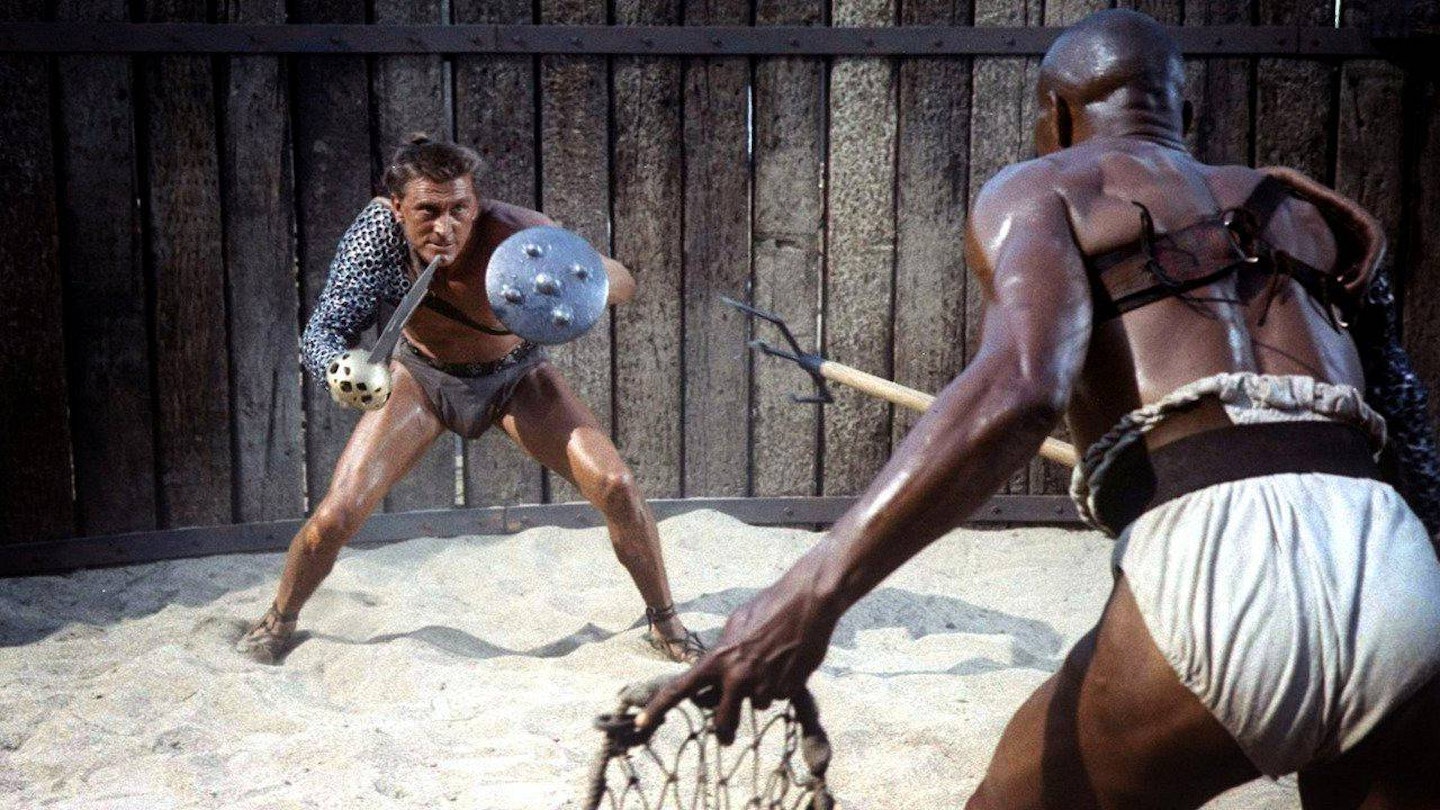

The gladiator training sequence and its pay-off in the "matched pairs" fight bests in 40 minutes the whole length of Gladiator (2000). We see the raw slaves drilled and pounded until they are perfect killing machines, with the unforgettable image of the trainer daubing Douglas' naked torso with different coloured paints to illustrate the varieties of wounds ("always go for the quick kill.") The two duels, one seen only through the slats of the pen as Spartacus and Draba (Woody Strode) wait their turn, and one between sword and trident staged in the sandy arena, are both a backdrop to a bit of intrigue between Crassus and his dim supporter Glabrus (John Ball), and a perverse distraction for ladies Helena (Nina Foch) and Claudia (Joanna Barnes).

The women are more interested in how few clothes the well-muscled fighters are wearing than in their lives and deaths. In a neat bit of plotting, Crassus' casual insistence on a minor fight to the death triggers the revolt, started not by the defeated Spartacus but by the victorious Draba, who dies trying to attack the audience (Olivier sneers superbly as he stabs Strode in the neck, blood splashing his face). Too intent on scheming against Gracchus, Crassus doesn't even consider that the slaves could cause him any trouble.

Douglas was always great in movies that required suffering.

Douglas was always great in movies that required suffering, and he often played roles that involved extreme mortification or even mutilation (no other Van Gogh hacked off his own ear with such conviction). Here he is at his best under the lash or up on the cross, almost relishing his own agony and burning with righteous fury. The irony is that even as a free man, Spartacus is a slave. He serves Crassus' interests by riling the people of Rome to the point where they are forced to call on his military genius, transforming him into a virtual dictator to save them from an enemy who only wants to go home.

Spartacus' merry rabble swarms across country to face a Roman army that, seen from a distance, resembles either a group of ants moving in perfect formation or living chessboard squares marching in order — an unbeatable, fascist machine. It's a breathtaking moment, which forces you to realise that Kubrick (before CGI) had to command extras as rigidly as Crassus runs Rome, and it takes Douglas' death on the cross to trump it.