Since making his debut with the disastrous Alien 3, David Fincher has struggled to find material worthy of his indisputable technical talent. This is nothing new; after Stanley Kubrick released Barry Lyndon in 1975 his assistant recalled hearing the nightly thud of books hitting the wall, until at last there was silence: Stanley had picked up Stephen King's The Shining, and the rest, of course, was history. Like Kubrick, Fincher has dabbled in a variety of genres too, but after the mixed reception afforded Benjamin Button, a respectable but strangely lightweight Oscar bid, The Social Network seems an unusual choice, even for him. It's talky, it's dorky, there's very little action, and, in the grand scheme of things, it's almost literally yesterday's news. But it has a quiet power, and, beneath the surface, there's perhaps more going on here than immediately meets the eye.

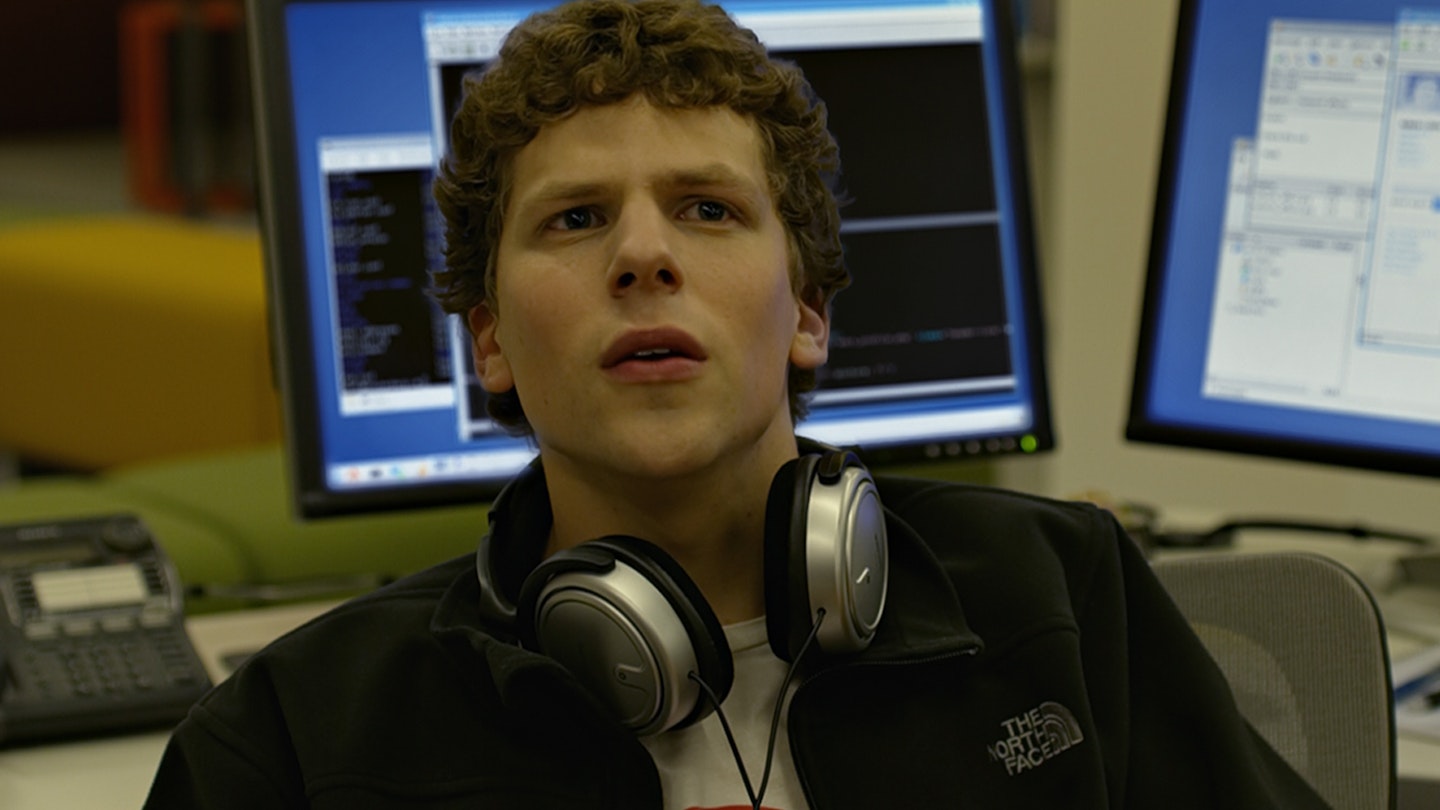

The Social Network is, first and foremost, about a paradox. It covers the founding of Facebook, a pioneering internet tool that, while bringing the world together, drove five individuals apart, and in doing so made its instigator, 26-year-old former Harvard student Mark Zuckerberg, recent history's youngest billionaire. Zuckerberg is played here by Jesse Eisenberg, who is simply superb as the conflicted genius, an emotionally isolated, social-climbing outsider with an unpredictable set of motivations and allegiances. Zuckerberg sets up his groundbreaking website for a number of reasons, partly out of spite, partly out of competition and partly because it's “cool”. But not, it seems, with anything as mundane, or forward-thinking, as a mission statement or a business plan.

Whether the real Zuckerberg is anything like this is another matter, and one that the filmmakers don't much care about (as a minor player says at the end, every creation story needs a demon). But if Zuckerberg is the moustache-twirling villain of this piece, the equally 'real' characters around him function with a similar degree of shorthand. Primarily, there is Andrew Garfield as the fresh-faced Eduardo Saverin, who is Zuckerberg's best friend at Harvard. Saverin gives Zuckerberg the money to start the operation, a loan of £1,000, but as the Facebook project grows, Saverin gets increasingly ostracised by his one-time best bud. In the meantime, also on Zuckerberg's elbow list are the Winklevoss twins (Armie Hammer and Josh Pence). The twins are star Harvard rowers who employ Zuckerberg to help them develop their own website, but instead of doing what's asked of him, he leads them a merry dance, apparently stalling their project to give himself time to advance his own.

Into this maelstrom of conflict steps Napster founder Sean Parker, played with seductive relish by Justin Timberlake as a louche libertarian who appeals to all of Zuckerberg's most reckless instincts. Parker is presented as the catalyst that turns Zuckerberg from amateur to pro, which he does, over cocktails, with a single anecdote: the sad story of Roy Raymond, the bankrupt 47-year-old founder of Victoria's Secret who committed suicide in 1993 after the company he sold for $4m became a billion-dollar business. Zuckerberg seems to be drinking this in, or as much as he ever seems to be drinking anything in. In fact, part of the fun of Eisenberg's performance is that he never gives anything away, which works nicely alongside the wistful Garfield and Machiavellian Timberlake.

The Social Network's plus points are immediately visible, notably in a long pre-credits scene that sees Zuckerberg in a bar with his soon-to-be-ex-girlfriend, Erica (Rooney Mara): Aaron Sorkin's rat-a-tat dialogue is established right there, and it never lets up. Likewise, Fincher's direction – comparatively restrained, except for an exhilarating, kinetic rowing sequence at the Henley Regatta – mostly aims for clarity and tight control. His colour palette is vital to this, being warm, sunny at times and even cosy in darkness, which comes in handy when zig-zagging between two potentially confusing timelines and two distinct court cases. The film's flaws, however, take a little longer to reveal themselves. For one thing, there isn't really that much to invest in; although Fincher gives it the adult veneer of a modern-day All The President's Men, the stakes aren't that high. This is a story in the public domain that's not about the public domain: its key players come from a rarefied world (indeed, the very first incarnation of Facebook, ironically enough, was deliberately exclusive and only available to subscribers with a Harvard email address). There's also the fact that Eisenberg, having dominated the first hour, suddenly steps back to make way for Garfield, and his presence is much missed.

That there's not a vast amount really going on here is beyond dispute, since there are no deaths or murders (so far) in this case, and not only are Zuckerberg's legal woes well documented, they barely add up to a paragraph on his rather skimpy Wikipedia page. So what would attract Sorkin and Fincher, 49 and 48 respectively, to such a slight story? The feeling that leaves the cinema with you is that The Social Network is intended as a portrait of the times, and its understatement is deliberate. Just 20 years ago, Wall Street was doing the same thing but bigger, with giant egos and huge deals. Now, although the payday-potential is even higher, the politics are those of the sandpit not the boardroom. Zuckerberg wants to be special, the centre of attention. Saverin is peeved that his best friend has a new best friend, and won't play with him any more. Meanwhile, the Winklevosses are stamping their feet because can't get a break: why, just because they're rich, they're handsome and they're excellent sportsmen, can't they be smart too? (Fincher has a lot of fun with that.)

It's hard to say how Fincher's film will be received today; indeed, Sorkin's last script, the concise and insightful Charlie Wilson's War still hasn't had its due, and in the UK, The Social Network's allusions to the social hierarchies within the US college system may not strike home. But it does have some interesting things to say, not just about the astonishing power that young people wield in the computer age (remember the line in In The Loop: “You know they're all kids in Washington. It's like Bugsy Malone, but with real guns”) but about the perspective that comes with youth.

The Social Network might even be a black comedy about that; Zuckerberg is obsessed with being cool, popular, first, but is he doing a good thing, and what about the social repercussions of his invention, which has since spread to every corner of the globe? Is he a crook? A rip-off artist? An arch manipulator? Fincher and Sorkin never close the book on any of these allegations, but they don't really need to because, in their version of the story, it doesn't matter. The closing song says it all: The Beatles' Baby You're A Rich Man, which asks the question, “How does it feel to be one of the beautiful people?” Zuckerberg doesn't know. But then, as the film slyly suggests, why would he? He's from a logged-in, left-out generation that knows little of beauty and even less of feeling.