The history of special effects technicians deciding to direct is not a particularly distinguished one. Chris Walas (The Fly) delivered the insipid The Fly II, Tom Savini (Friday The 13th) inexplicably remade horror classic The Night Of The Living Dead, while Joe Johnston (Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom) delivered ILM showreel Jumanji.

American movies of the 70s, the decade of Vietnam and Watergate, tend to have an angsty, anxious feel, and Silent Running is sci-fi's contribution to that uneasy national mood. Penned by Derec Washburne and the unlikely pairing of Michael Cimino (who would bring down UA with Heaven's Gate) and Steven Bochco (the creator of Hill Street Blues).

It's hardly groundbreaking sci-fi to hint that technological advances may have a downside. But in the main it is either alien invasion or nuclear war that devastate the Earth. Silent Running however voices the early popular inklings that unchecked technological development may destroy, or at least seriously compromise, the planet. Lowell, who recognises that Earth is less of a place because it lacks green spaces, is pretty much a voice in the wilderness. "There's hardly any more disease, there's no more poverty, no-one's out of a job" one of the astronauts comments, bemused by his colleague's insistence that the planet is soporifically monotonous without its flora and fauna.

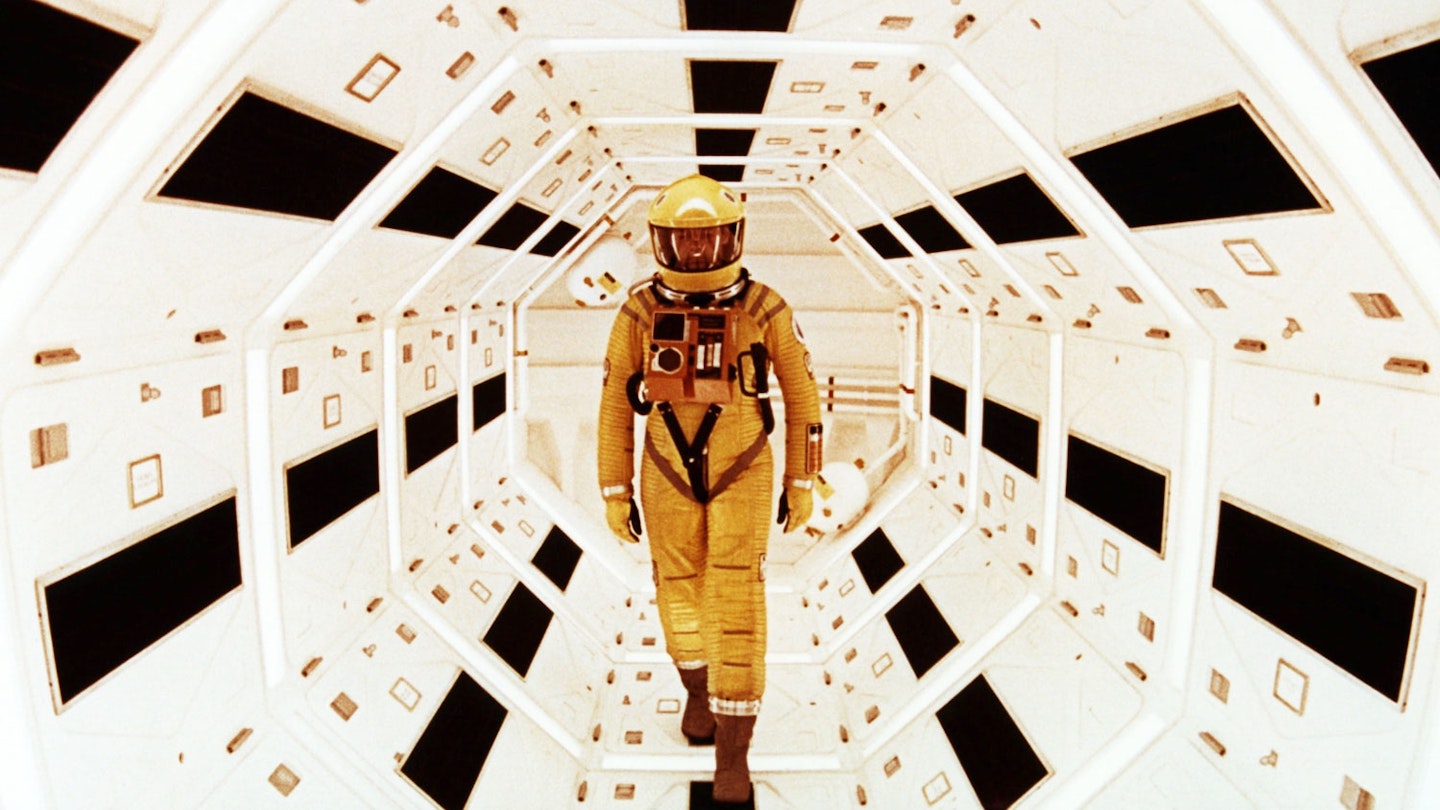

Given the fact that in the intervening two decades ecological issues have moved into mainstream politics it's difficult to believe that this was a genuinely radical position in 1972. It's this unusually strident, obvious, political stance that distinguishes Silent Running from the Commie infiltration fantasies of the 50s or the action packed space operas that emerged at the end of the decade. Trumbull shot his debut for a paltry $1 million in a couple of abandoned aircraft hangers reducing his costs by minimising the cast and spending the bulk of the budget on the gracefully deployed effects instead. In order to reduce costs further he hired a group of inexperienced college kids to help him. One, John Dykstra, would pioneer the effects for Star Wars.

For the drones he employed four multiple amputees who operated the different robots at different times (it's worth noting that these squat, speechless robots predate R2D2 by five years). As a first movie it's a daring choice. For the bulk of the film Lowell has no one to talk to but his drones, which he names Huey and Dewey. Trumbull fills the time with a number of montage sequences which have Lowell wandering around the station in positively messianic robes munching on the garden's produce. Dern's performance, all wistful glances and pained sighs, keeps you watching (in fact Dern's at his worst when he's got other actors around him), but it's the conclusion that really gets the lachrymal ducts going. The final image, of the remaining drone tending a flower with a battered child's watering-can is the kind of bittersweet ending that focus-groups, test-screenings and nervy execs have made virtually extinct.