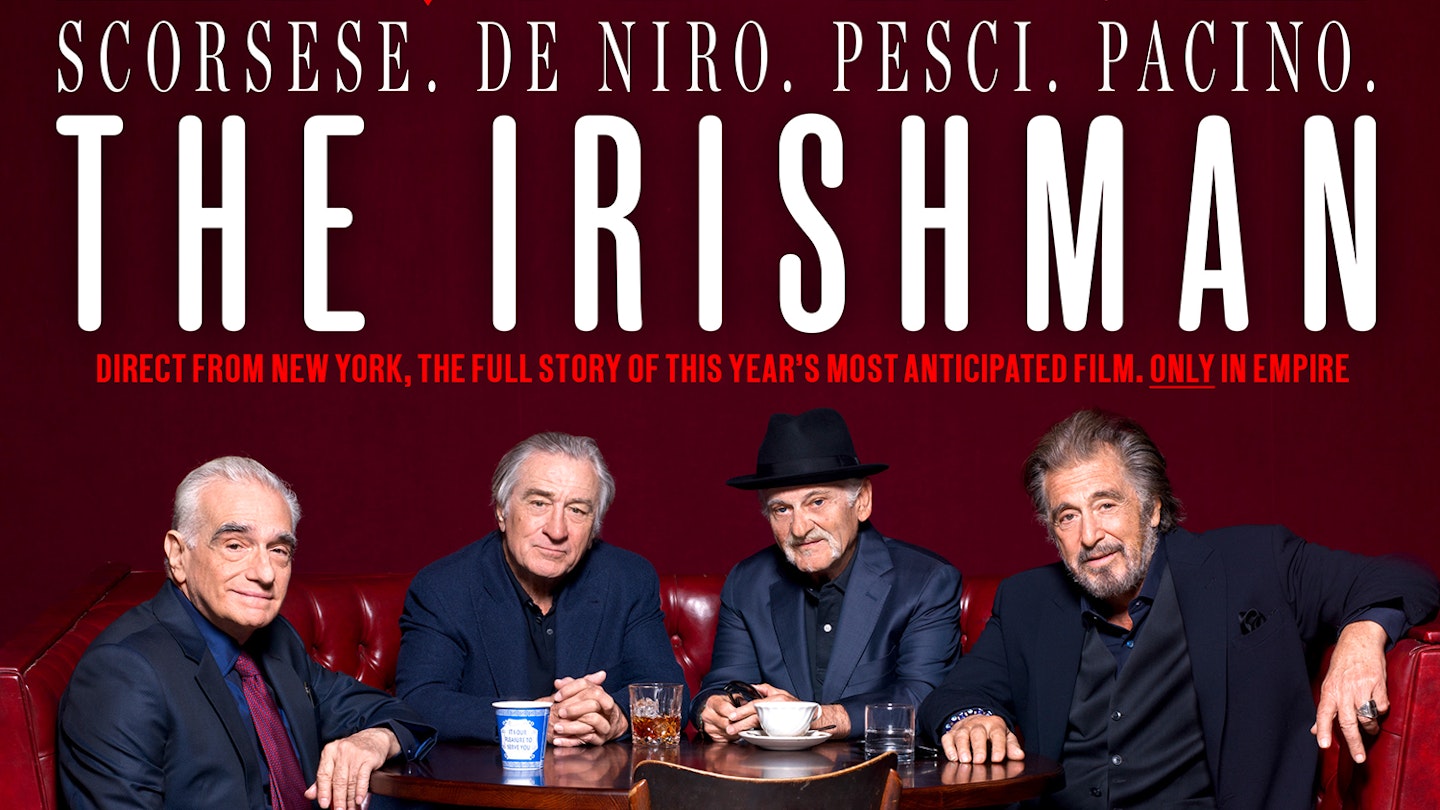

At the time of writing, it is not clear what Pope Francis thought of Martin Scorsese’s Silence (the rumour is four out of five mitres) after the special Vatican screening, but he surely must have admired its burning sincerity. Adapted from Shūsaku Endō’s 1966 novel (previously made into a film in 1971), it is a passion project as personal to the director as anything involving Italian gangsters. From 1967’s Who’s That Knocking At My Door to now, Scorsese, a failed priest, has conducted a 50-year investigation into how spiritual feeling butts up against the flesh and blood world. This is the clearest articulation of his ideas to date.

Beautifully made, staggeringly ambitious and utterly compelling.

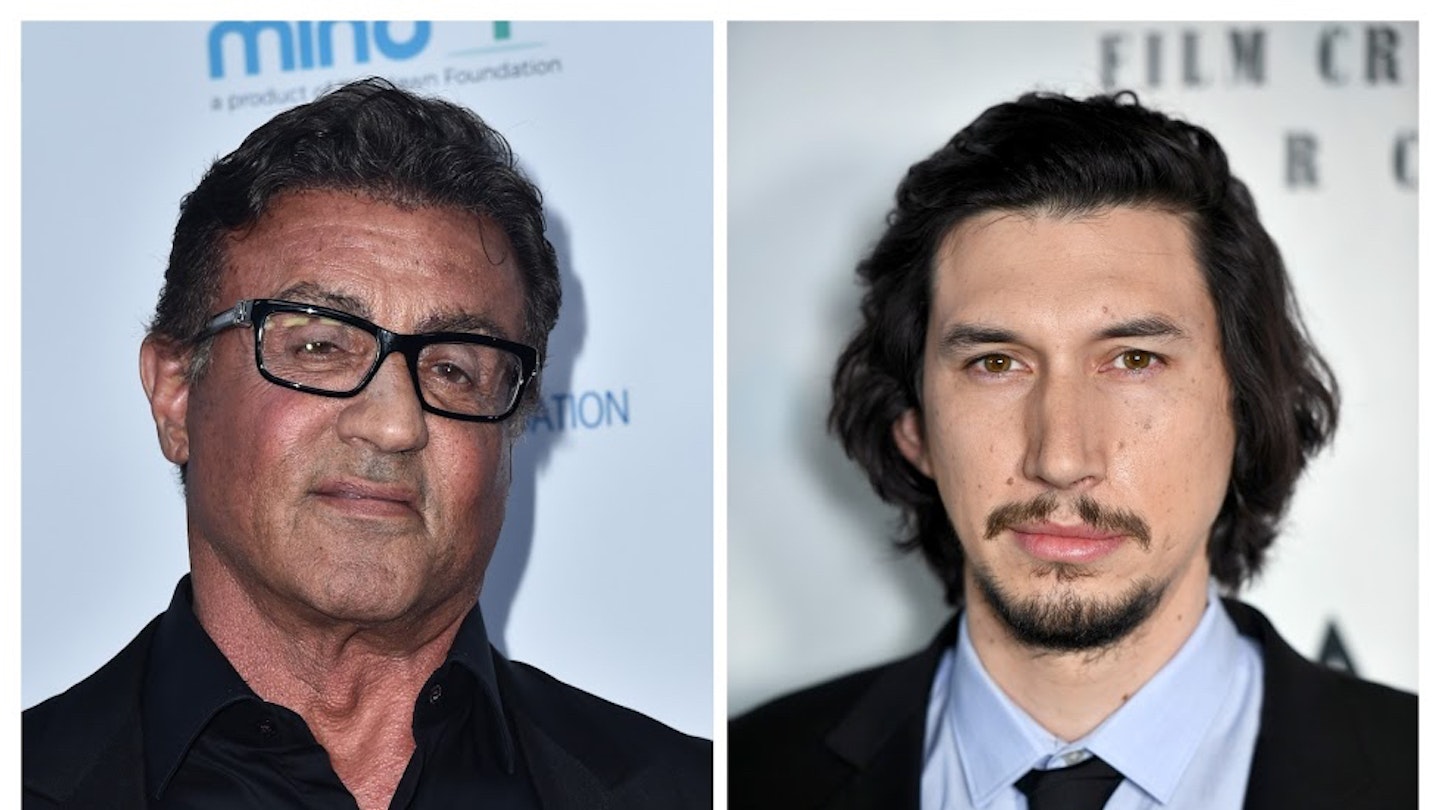

On paper, Silence sounds like a devout-men-on-a-mission movie as Fathers Garrpe (Adam Driver) and Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) go in search of their missing mentor (Liam Neeson). But the actuality is lower octane. Arriving in Japan, the priests are drawn into the struggle of ‘hidden Christians’ clandestinely practising their faith while the Shogunate Inquisitor (Issei Ogata) and his men relentlessly stamp it out, chiefly through baiting Christians to tread on fumi-e, copper images of Christ, to renounce their faith. As you’d expect, Scorsese doesn’t flinch from cruelty — men are drowned tied to crucifixes, women set on fire — but, working with DP Rodrigo Prieto, it is shot through with a painterly beauty. A God’s-eye view of a ship at sea. Severed heads in the mist. The images are as poetic as the dialogue.

The priests get separated and Garfield’s Rodrigues takes centre stage. The second half becomes a battle of wills as the Inquisitor’s interpreter (a terrific understated Tadanobu Asano) tries to slowly separate Rodrigues from his faith through whispered mind games. It’s a film about Rodrigues’ interior journey and, in a career-best performance, Garfield realises it beautifully, his rock-solid belief slowly undermined by doubt. When Rodrigues is asked to step on the fumi-e to save the lives of converts, it doesn’t end how you expect.

If the film is steeped in Japanese cinema like Mizoguchi and Kurosawa, it also bears strong ties to European heavyweights. It is a rare American film that can stand intellectually with Ingmar Bergman but Scorsese doesn’t flinch from the big questions: chiefly why does God remain silent as believers are drawn into cruelty in His name? As such, it’s a slow, tough watch. Sometimes Scorsese overplays his hand (Garfield’s reflection in a stream morphs into Jesus) but this is the director working without his usual arsenal. Save a twisty-turning Cape Fear camera move at a crucial point, there’s little in the way of trademark visual pyrotechnics, razzle-dazzle editing or intrusive music. It’s as if Scorsese doesn’t want anything to detract from his story. At a time when Christians are still persecuted in Syria, Egypt, Pakistan and beyond, when we venerate the creeds at the expense of the message, he understands this tale from the 1600s couldn’t be more timely.

.jpg?ar=16%3A9&fit=crop&crop=top&auto=format&w=1440&q=80)