In most cases, it’s the quality of the human drama that makes a documentary great, not the detail on the arena in which that drama plays out. You don’t need to be into The Dandy Warhols to dig Ondi Timoner’s Dig!. You don’t have to be a bear enthusiast to revel in Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man. And if all Formula 1 means to you is the incessant roar- whine of pimped-up go-karts on Sunday afternoon telly, that’s no reason not to discover Asif Kapadia’s Senna, a truly remarkable and affecting film.

The Hackney-born Kapadia has (aside from 2006 horror The Return) thus far marked himself out as a purveyor of epic arthouse, setting taut dramas against vast, real-world backdrops: subcontinental deserts in his impressive 2001 debut The Warrior, arctic tundra in his underrated last movie, Far North. So it’s no surprise that his first foray into documentary should find him balancing the epic and the intimate, with Kapadia shunning the dark art of reconstruction and small-set structure of talking-head interviews, instead going for something far more ambitious.

Kapadia has assembled a vast array of material (about 15,000 hours), from home movies to newsreel to on-car camera recordings, and even never-seen backroom videos of drivers’ briefings to tell Senna’s inspiring, tragic story entirely through original footage and voiceover (although never Kapadia’s own). This gives the film a fluidity and strength unimpeded by cutaways to people reminiscing in their studies — although you do suspect that the depth and breadth of Kapadia’s access involved its own compromises. Because Senna is very much a panegyric, its subject undoubtedly lionised. The film treads lightly over Senna’s personal life (not mentioning his relationship with a 15 year-old girl), and avoids playing up the driver’s darker professional side (his assault on Eddie Irvine in 1993).

Kapadia can argue the irrelevance of such things to the story that he’s telling, and with good reason. One could just as easily mention the director’s play-down of the incident where the three-time world champion once dived to the aid of crashed French driver Érik Comas mid-race, seriously risking his own life (it only appears as footage over the end credits); or his omission of the fact that in the wreckage of Senna’s fatal crash was a furled Austrian flag, which the driver had planned to wave during his (likely) victory lap in tribute to Roland Ratzenberger, who had died one day earlier during a qualifying race. Quite simply, you can’t include everything.

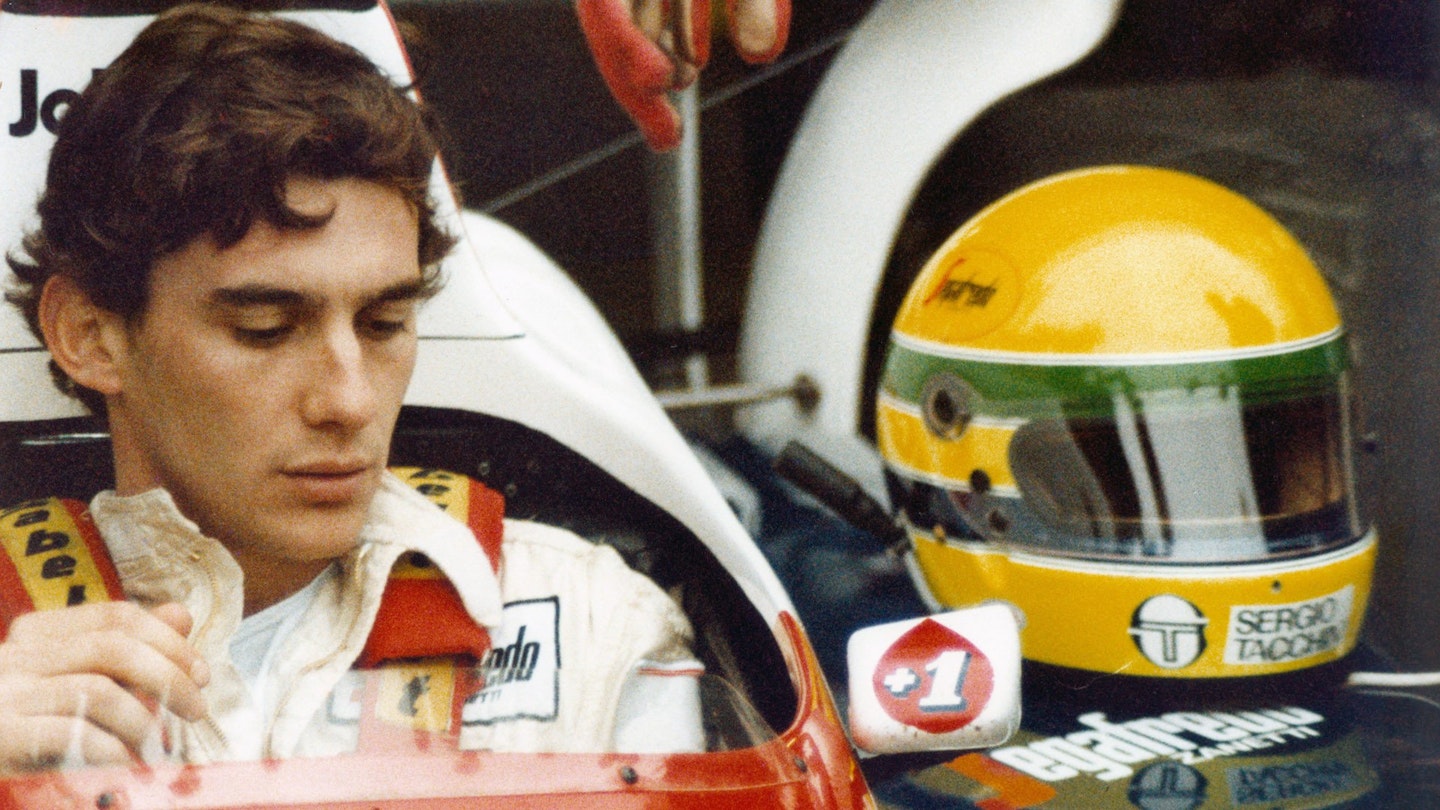

Besides, it would have been hard for anyone collating this material not to become enamoured of Senna. While his is hardly a rags-to-riches story (Formula 1 teams hardly go talent-spotting in the favelas, and Senna was indeed born into enough wealth that Daddy could pay for his go-karts), he’s a compelling individual. It’s not just his aquiline looks, that boyish smile or the soft-spoken appeal that leavened his towering self-confidence.

It’s also because, as Kapadia highlights, Senna challenged the politics of Formula 1, channelling a naive faith in the best man winning into his famous clashes with one-time McLaren team-mate Alain Prost — portrayed here, perhaps unfairly, as a weaselly character (only emphasised by Kapadia including Prost’s clumsy letching over Selina Scott on the Wogan chat-show) — and pitbullish former FIA boss Jean-Marie Balestre. “If you no longer go for a gap, you’re no longer a racing driver,” Senna once blustered, not accepting that he should have gone easy on Prost while at McLaren. Prost retorted with a comment that was, of course, horribly prophetic: “Ayrton has a small problem. He thinks that he can’t kill himself. And that’s very dangerous.” Which is fair comment from a man who’s collided with Senna at 170mph.

Senna’s maverick nature, and the battles it caused, form the thrust of Kapadia’s film, and it results in some astonishing moments, such as Senna’s devastated reaction to the death of Ratzenberger and the hospitalisation of Rubens Barrichello during that fateful weekend in Imola, San Marino, which ironically inspired Senna to recreate the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association to improve track safety, mere hours before his own death. (There hasn’t been an F1 fatality since Senna’s.)

It’s also finally worth noting one other major achievement of Kapadia’s film: while Senna himself is the subject rather than Formula 1, Kapadia’s use of race footage — particularly of Senna’s own brilliance on the track, best illustrated by the driver’s talent in exploiting wet conditions — will make even those who find motor-racing a noisy bore feel the visceral thrill of high-velocity competition.