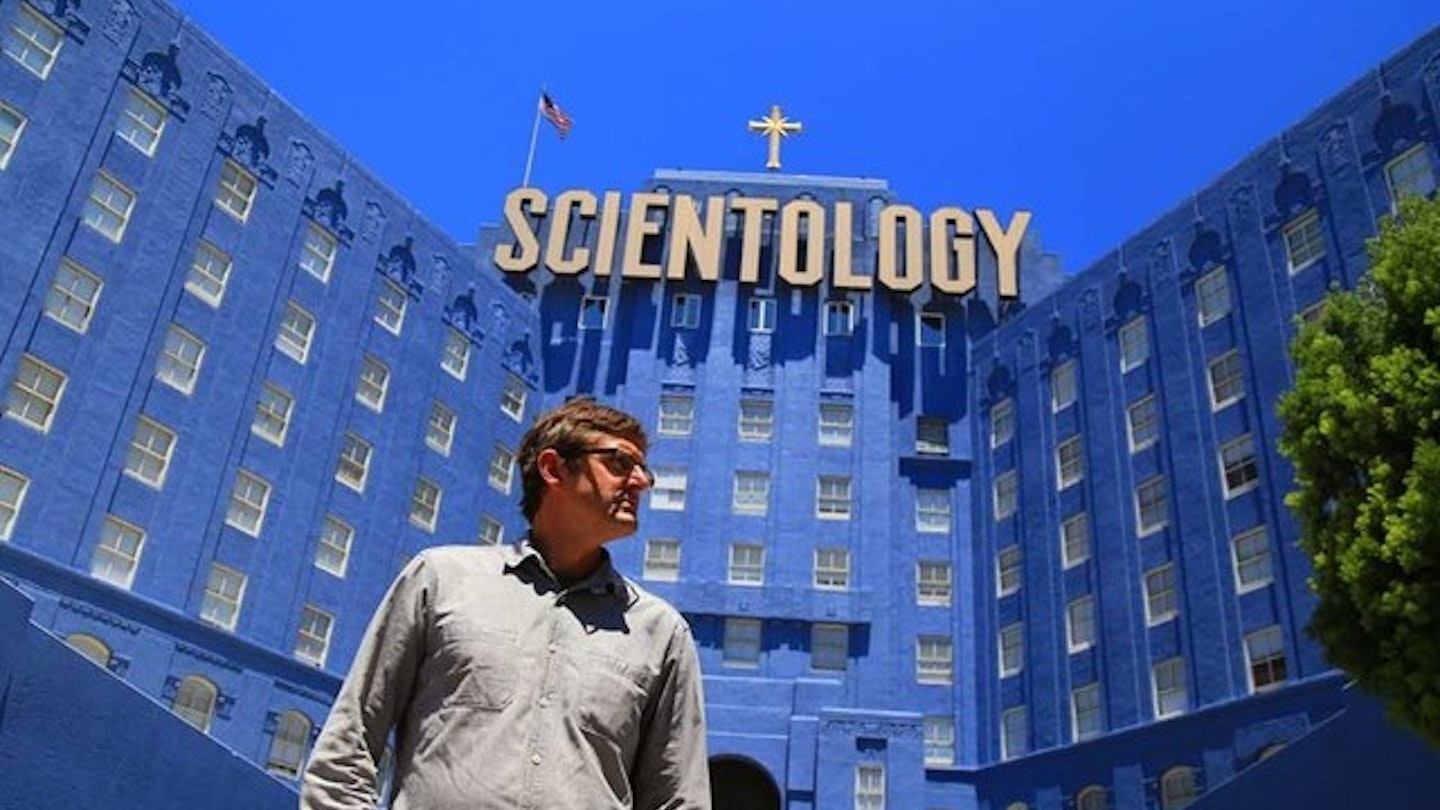

Making a Scientology documentary will always guarantee you an audience. A small army of lawyers, in the first instance. Alex Gibney estimates 160 legal eagles watched last year’s Going Clear before its release, and it’s hard to imagine Louis Theroux’s addition to L Ron Hubbard’s DVD cupboard wasn’t given a similarly fine-toothed treatment. Few people are more likely to goad this litigious organisation than a man who’s turned the tables on everyone from white supremacists to Westboro Baptist’s rabid flock just by asking the right questions, listening a lot and being disarmingly goofy.

Making a Scientology documentary will always guarantee you an audience, even if it's just a small army of lawyers.

But while the BBC’s mild-mannered assassin brings all his weapons to bear here — awkward silences, innocent but insistent probing, vast reserves of likeability — he somewhat meets his match with Scientology. Stonewalled by its bug-eyed loyalists, threatened by its lawyers and unable to get close to its leader David Miscavige, Theroux instead chooses to recreate its practices (and, more pertinently, malpractices) using actors he casts in sessions, a little guidance from former Scientologist-turned-whistleblower Marty Rathbun and the odd visit to headquarters.

Unlike one of the main inspirations, Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act Of Killing, Theroux’s gambit is only half successful. Oppenheimer’s film has real people recreating their own shocking acts of genocide; here Theroux’s actors make willing surrogates, but they’re no substitute for access to the organisation itself.

Where they do pay off is in a recreation of the infamous Hole, a prison for senior Scientologists (or Sea Orgs) where the most extreme abuse is alleged to have taken place. It leads to the film’s most impactful scene, a depiction of bullying and the abuse of power that’s shocking even on a film set. The treatment of ‘Suppressive Persons’ — Scientology’s supposed apostates — is tackled with terrifying gusto by the actor playing Miscavige. It’s clearly one role you wouldn’t want to go Method for.

At other times, though, the mock-ups are a blunter device. The actors sit awkwardly while Rathbun explains the organisation’s doctrines, and there’s little in his explanation of its world view, tools of manipulation and intimidation strategies that hasn’t already been covered in Going Clear and Panorama’s explosive 2007 documentary Scientology And Me.

That’s not to say Theroux doesn’t burrow gently under his subject’s skin. The best scenes lay bare the paranoia and insecurity that seeps from the organisation. “After four hours of the same car being behind you,” he notes during a drive through LA, “you start to get suspicious.” Often lingering on the edge of his frame are edgy footsoldiers, awkwardly filming him as his crew films them. Only the good-natured Theroux seems to stand between them and an Anchorman-style camera crew battle.

My Scientology Movie is full of such meta moments, including a long argument with

goons outside Scientology’s dusty Californian compound about whether he’s on its land illegally. It ends with them slinking off. “You don’t have to go,” Theroux shouts after them. “You’re not trespassing.” It’s the film in microcosm: funny, occasionally menacing, but ultimately stranded just outside the inner sanctum.