Towards the end of Thomas Keneally's 'non-fiction novel' Schindler's Ark (as it is known in the UK), Liam Neeson's reformed profiteer Oskar Schindler reassures his trusted plant manager Itzhak Stern (Kingsley) that he will receive "special treatment" once he reaches the concentration camp. Stern demurs, recalling the directives from Berlin that have recommended 'special treatment' for all Jews. "Preferential treatment, then," Schindlers sighs, slightly piqued. "Do we have to invent a whole new language now?" Stern does not miss a beat. "I think so," he says.

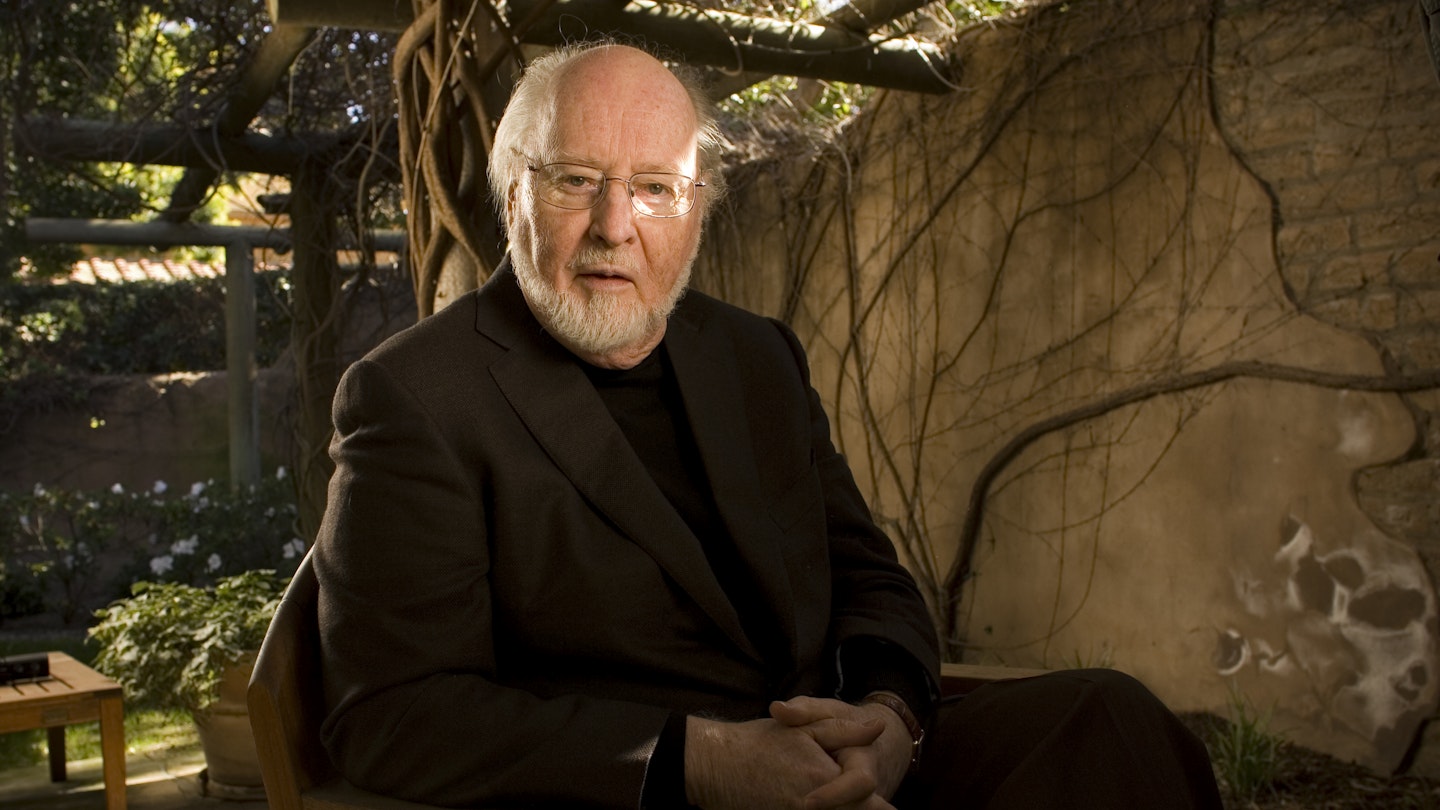

That a mere movie - much less a motion p[icture authored by cinema's most successful crowd-pleaser - should flout Steiner's dictum would have horrified the post-War elite and remains controversial to this day. 'Schindler's List' is at once the most celebrated and most keenly criticised film in the Spielberg canon. During an awards season that resembled a victory lap, it became commonplace to talk of 1993 as Spielberg's annus mirablis - that year also spawned the monster hit 'Jurassic Park' - and of 'Schindler's List' as his 'Bar Mitzvah movie', the masterpice that signalled his emergence as an emotionally adult filmmaker.

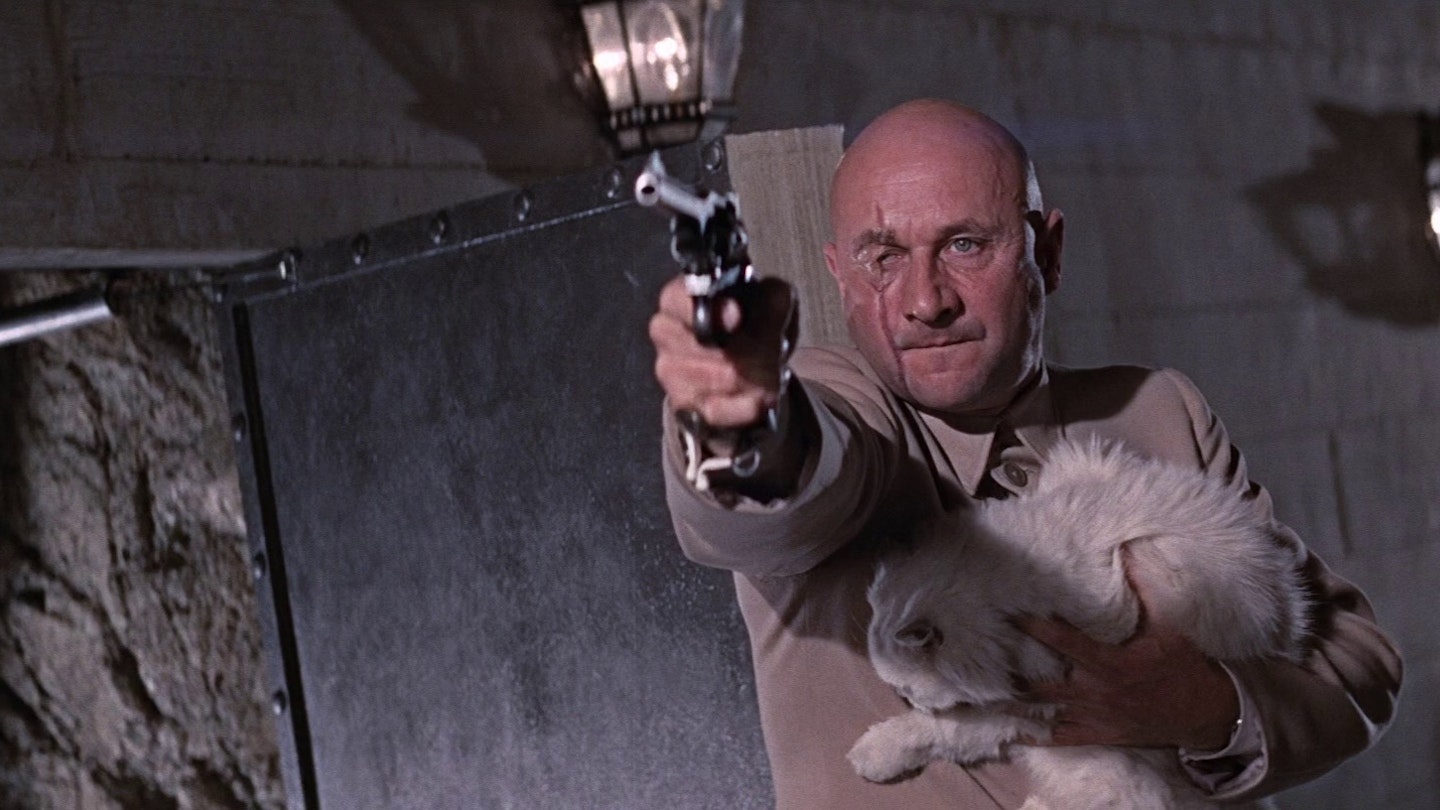

And yet elements in the critical community cried foul, noting with disgust that the director of 'Jaws' can be found pulling the strings of an overwrought shower scene - where an expected gassing does not occur - or, smugly, that typically Spielbergian sentiment creeps into Schindler's over-emotional goodbye.

And that was the least of it. Among certain liberal and Jewish groups, the very notion of a holocaust movie with a blonde Nazi as the central protagonist, and 1,100 survivors taking centre stage when six million perished, sparked furious debate.

Despite Spielberg's avowed intention to check his "desire to entertain, 'Schindler's List' the movie remains true to the director's first, instinctive, reaction to Keneally's book - "a helluva story". This is no accident. Without the narrative sweep, the majority of the audience simply would not journey into the very darkest places Spielberg knows they must eventually face.

One of the most persistent canards of highbrow criticism is that greatart should not be easy. For the millions of people who watched the little girl in the red coat dumped onto a horrifying mountain of burning corpses, the idea that 'Schindler's List' should, infact, be more gruelling, that it should be less inspirational, that it should include more death, is hard to countenance.

A purely horizontal movie - one without a dramatically interesting protagonist or a focus on survivors - might satisfy the most searching complaints, but it would be almost impossible to stomach. (Spielberg is in fact so anxious to keep death gate-crashing into what is fundamentally a survivor's story that occasionally, as with the shower scene, he stumbles slightly.) As it stands, 'Schindler's List' which Spielberg thought would lose every dime of its $22 million budget, made an unprecedented $321.2 million at the box office. That kind of reach for a film of this nature is nothing short of a miracle.

When he made his famous call for silence, George Steiner could not have known that, by the last decade of the 20th century, Holocaust denial would have become a cottage industry, nor that 25 percent of young Americans would have little idea what the word 'holocaust' even meant. And he would not have dared imagine that the chilling language of Nazi directives would find echoes in the 'ethnic cleansing' once more taking place in Eastern Europe.

If no mere movie can become an "absolute good" - to borrow Stern's description of the list itself - then by 1993 a popular motion picture about the Holocaust had become an absolute necessity. That the picture born of this necessity was Steven Spielberg's 'Schindler's List' is enough to restore your faith in not just the medium, but also the human race itself.