Although Robocop would be the film largely responsible for introducing English-speaking audiences to the mad, bad world of Paul Verhoeven, it was by no means his first brush with Hollywood. Five years before unleashing his half-man/half-cyborg law enforcer on an unsuspecting public, the Dutch director was in the frame to direct Return Of The Jedi. He had been recommended to George Lucas by Steven Spielberg who greatly enjoyed Verhoeven's WWII epic Soldier Of Orange. Legend has it that Spielberg subsequently withdrew his support after viewing Spetters — a film Verhoeven directed wearing biker leathers and which followed the adventures of three motocross champions, one of whom turns homosexual after being gang-raped. "I suppose he was scared," Verhoeven would later comment, "that the Jedi would immediately start fucking."

Of course, given the rumpy-pumpy-oriented shenanigans of subsequent Verhoeven vehicles such as Basic Instinct and Showgirls it is reasonable to suggest that Spielberg would have been justified in his fears. But, ironically, before Robocop it was generally thought that the director was not too shag-obsessed for a big studio blockbuster but too arty. Indeed, Verhoeven films such as Spetters and Flesh + Blood had become arthouse favourites around the world. Certainly they seemed to have little in common with a film like Robocop which, on paper at least, is just another sci-fi shoot 'em up and not even a particularly original one at that. Set in a near-future Detroit where police matters are controlled by the all-

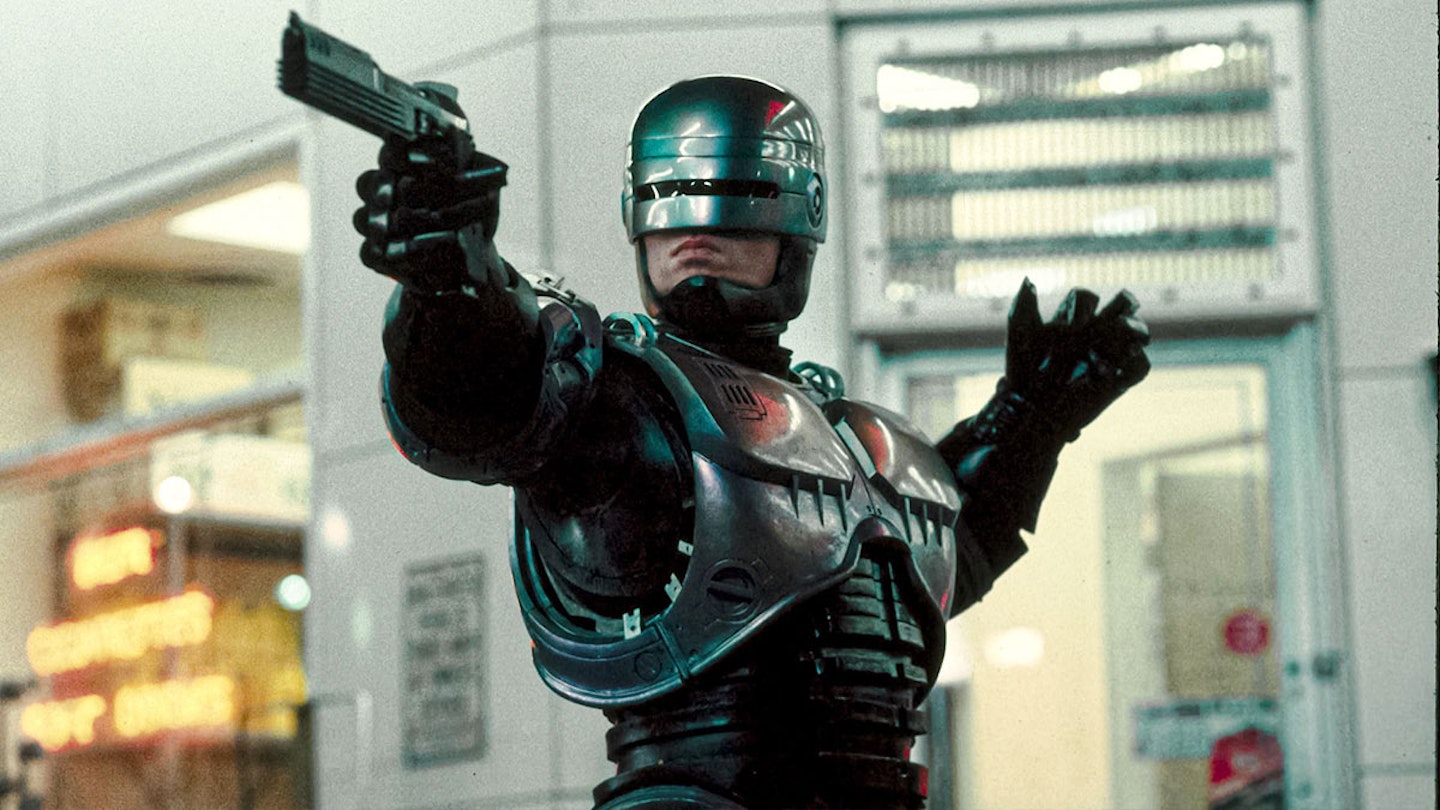

powerful OCP corporation the movie follows the travails of nice copper Alex Murphy (Weller) who, after being blown to bits by a gang of crooks, is brought back to life as the titular man-machine. Robocop's arrival is met with dismay by his more fleshy colleagues while problems arise when he begins to hunt down Murphy's killers — a trail that leads all the way back to the corrupt corridors of OCP itself.

In short, the plot of Robocop is essentially similar to any number of superhero tales with a smattering of Dirty Harry and Judge Dredd thrown in for good measure. But, in the hands of Verhoeven, the film became — like his later Starship Troopers — a satirical critique of the totalitarianism which he had seen first hand as a child growing up in the Hague. Verhoeven was little more than a toddler when the Germans invaded the Netherlands and his earliest memories are of a life dominated by jackbooted soldiers. He witnessed people "picking up pieces of pilots ". "There were a lot of uniforms in the Hague," Verhoeven has said of his childhood. "Living in an occupied country dominated by an evil empire is something that's close to me. Being a child of the war my tolerance for violence is larger than normal."

It was this love of mayhem combined with a biting comic attack on neo-fascist corporatism — most notably seen in the TV ads for products like the apocalyptic board game Nuke 'Em — which helped raise Robocop above the common sci-fi herd. Yet what really put the film ahead of the game was Verhoeven's technical expertise. The director was originally attracted to science fiction because he thought, being unfamiliar with American society, it would help his cause if he was allowed to re-imagine it. There is no doubt the genre suited his skills which had been developing since the late 60s when, during national service, Verhoeven made a propaganda film utilising helicopters, divers, an aircraft carrier and several divisions of marines.

Moreover, having ordered around half the Dutch navy, the director had few qualms going to battle with special effects wizard Rob Bottin — Verhoeven dismissed his early robot designs as "crap" — or Peter Weller who conceded that "it was the first time I was convinced I'd have a fist-fight with a director." Yet, even Weller — who endured months of torture within the suit — would eventually concede that the result was more than worth the aggravation.