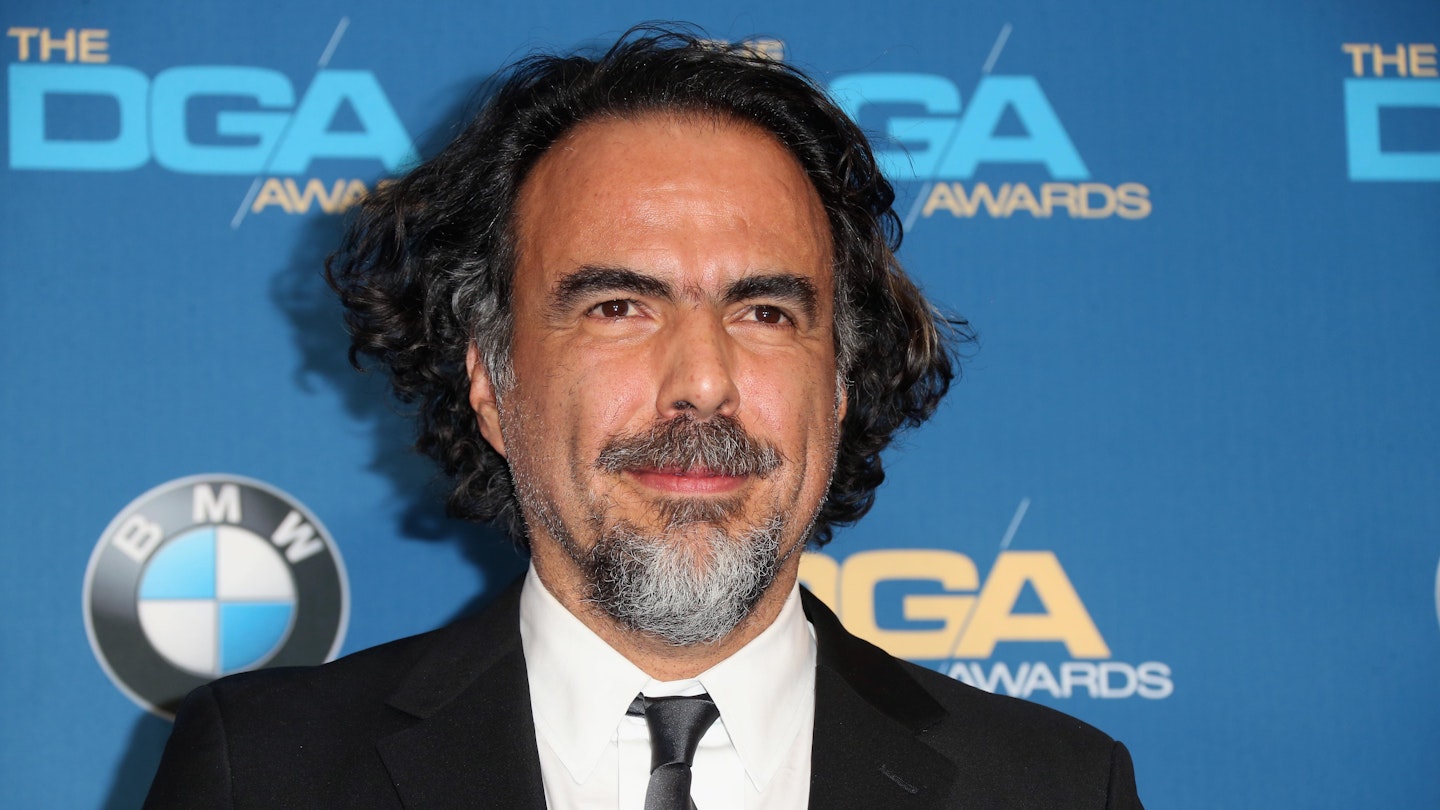

Revenge, goes the old Klingon proverb, is a dish best served cold. Which is good news for The Revenant, the new film by Mexican boundary-pusher Alejandro G. Iñárritu, because few tales of vengeance have ever looked quite so butt-clenchingly chilly. It's become the stuff of legend, a nine-month shoot in the wilds of Alberta and Argentina. But Iñárritu has come out the other side with an astonishing sensory experience, one that plunges the viewer into a sub-zero hell that often looks like heaven. It's likely to both storm the Academy Awards and play well on Kronos.

After sending up Hollywood with Birdman, Iñárritu has found inspiration in an even less civilised collective: the frontiersmen of the 1820s. As recounted in Michael Punke's source novel, a fur-trading venture up the Missouri River attracted a mixture of upright men like Andrew Henry (Domhnall Gleeson), young tenderfeet like Jim Bridger (Will Poulter) and black-hearted killers like John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy). But the focal point of the story is Leonardo DiCaprio’s Hugh Glass. The original Bear Grylls — and almost certainly history's toughest Hugh — he was an expert tracker who achieved folk hero status by surviving an ursine assault, then clawing his way out of the wilderness to hunt down those who betrayed him. Details about his life are hazy, which is all the better for allowing Iñárritu and star Leonardo DiCaprio to turn the grizzly man into a mythic force of nature himself.

The odds are stacked against him. In two blistering early set-pieces, the sheer brutality that mountain men faced back then is made clear. They are also a chance for ace cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki to show he's not slacking after winning consecutive Oscars for Gravity and Birdman.

The movie opens with a moment of serene beauty, gliding Terrence-Malick-like through a waterlogged forest as Glass and his son (Forrest Goodluck) hunt elk, just outside camp. Then Arikara warriors burst out of the foliage, cueing an eruption of distinctly non-Terrence-Malick-like carnage. It's a mesmerising, violent piece of action choreography, as Iñárritu's camera (the brand-new 6.5k ARRI 65, in case you were wondering) glides through the chaos. One jawdroppingly limber Steadicam shot pursues a character until he's killed, then switches to the killer until he's dispatched too, and so on, mounting and dismounting a horse and even plunging into water to capture a drowning. It would look like showing off if it weren’t so damn effective.

Equally bravura is the bear attack. In 1971's Man In The Wilderness, an equally loose take on the Hugh Glass legend that renames him Zachary Bass, Richard Harris is mauled by an off-camera beast. 2015 technology makes possible a far more intense sequence, with the enraged CG "grizz" coming off like a cross between Uncle Pastuzo and the demon Pazuzu. Though the visual effects are a little jarring in a movie that's otherwise entirely practical, nature red in tooth and claw has rarely been captured like this on screen. It's a devastating bout of savagery that leaves Glass with bones broken and skin rent open in awful ways.

DiCaprio's raw performance helps elevate what could have been just another man-versus-nature drama.

And so begins what could be termed The Passion Of The Leo. The supporting cast is uniformly terrific, particularly Poulter, looking on the verge of tears at all times, and Hardy, sometimes hitting Bane levels of mumbledom but emanating menace as the half-scalped villain of the piece. But for large swathes of the film it's DiCaprio on his own, and if this doesn’t land him that Oscar at last he may have to sign up for a Mother Theresa biopic.

Flinging himself into every harsh scenario as if atoning for all that Wolf Of Wall Street debauchery, DiCaprio is hypnotically good, whether scraping marrow out of a frozen bone, going full Gollum on a fish, or (in a moment that will surely become known as The Tauntaun Bit) keeping himself warm with the aid of a horse. He has maybe a dozen lines of dialogue, most of which are rasped through a torn throat, but you root for him with all your heart.

DiCaprio's raw performance helps elevate what could have been just another man-versus-nature drama, The Edge with furry hats, into a powerful ode to resilience. But this is Iñárritu's show. Some directors might have been tempted to follow an Oscar win by making a cushy comedy in the Bahamas – but the driven Iñárritu pushed himself and his crew to the limits against the elements. He defied conventional wisdom by shooting with natural light only, and in chronological order, and has emerged with something we have never seen before.

The imagery is sublime, primal landscapes straight out of an Albert Bierstadt painting and weird wastelands pulled from Glass' subconscious. The score, by Ryuichi Sakamoto and Alva Noto, is doomy and primal. And those eccentric grace notes that buoyed Birdman are present too: at one moment a character's ragged breath fogs up the screen. It took a crazed drive equal to Glass’ own to put together this mad feat of a film. At least nobody got mauled by a bear along the way.