Inspired perhaps by Strindberg's play, The Stronger, Ingmar Bergman wrote the screenplay for this 'sonata for two intruments' to stave off boredom while in hospital with a virus. Discarding plans to call the picture cinematography, he alighted on Persona, as it was the Greek word for 'mask'. However, it was also the name given by psychologist Carl Jung to the outer self that stood in opposition to the inner image or `alma' and this premeditated nomenclature found further echo in the fact that Elisabet's surname recalled Albert Emanuel Vogler, the artist who sapped the energy of others for his artistic identity in The Magician (1958).

Bergman so blurred the line between reality and fantasy in this complex, but compelling drama that some have claimed that Alma and Elisabet are projections of a single character whose actual selfhood defies identification. Others have suggested that all of the events from Alma's falling asleep following her one-sided argument with Elisabet is a dream, in which she gains a greater insight into both her own and her patient's emotional status by journeying into her subconscious.

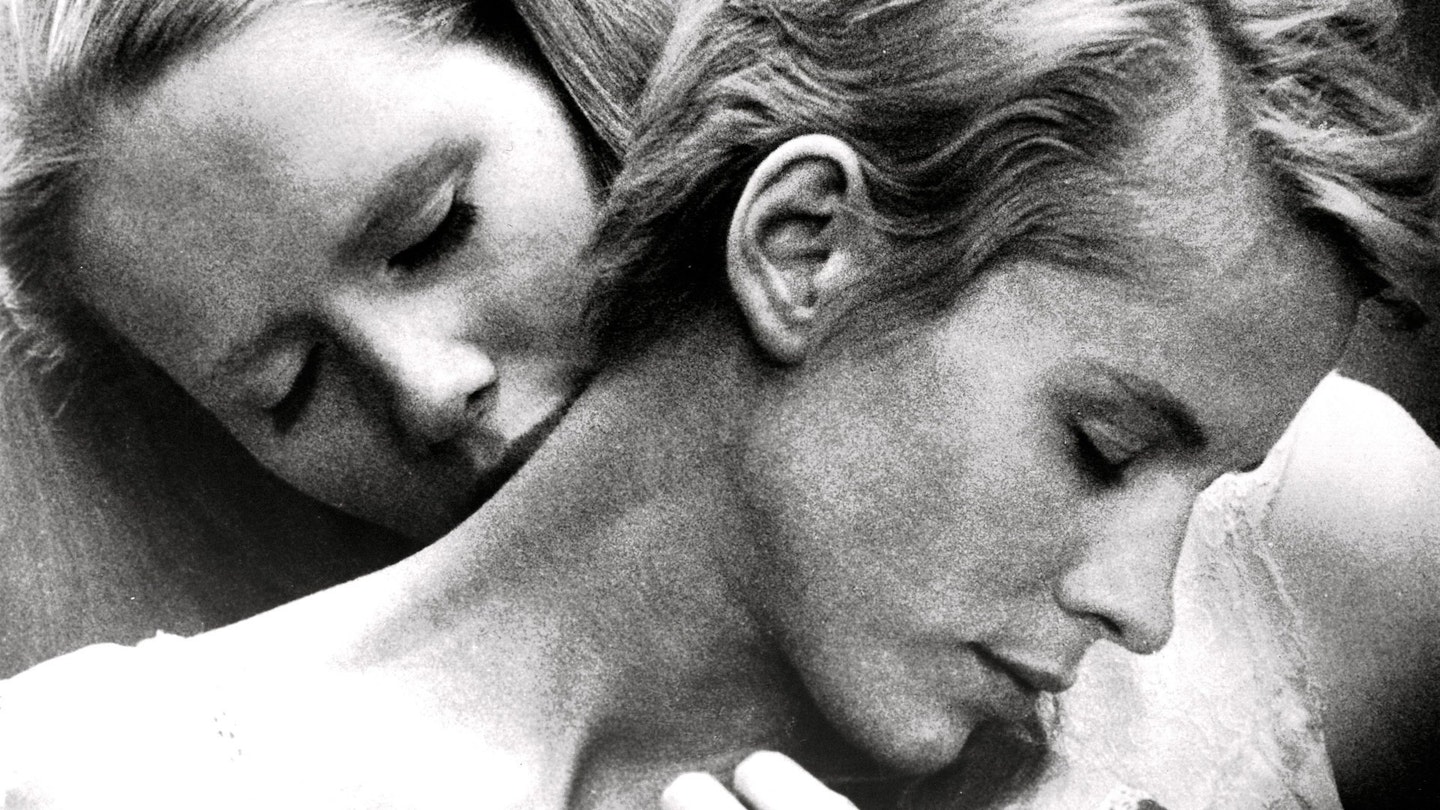

What makes these dramatic ambiguities all the intriguing is the manner in which Bergman emphasises their innate filmicness. In addition to showing the leader numbers on screen before his opening montage depicting images of death, fear and humiliation, Bergman consistently draws the viewer's attention to the artificiality of the action by repeating passages of dialogue, briefly depicting himself and his crew in the process of recording a scene and halting the flow altogether by causing the celluloid to melt. Even the famous merging of Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson's faces into an iconic composite serves a dual purpose, while also subverting any conclusions that we may have drawn about the psychological source of the scenario and the emotional state of the protagonists.

Clearly reflecting Bergman's despondency at an increasingly turbulent world, this devastating treatise on mortal and intellectual impotence is also a technically audacious critique of the condition of cinema that rivals anything produced during the nouvelle vague, whose influence is evident in almost every frame.