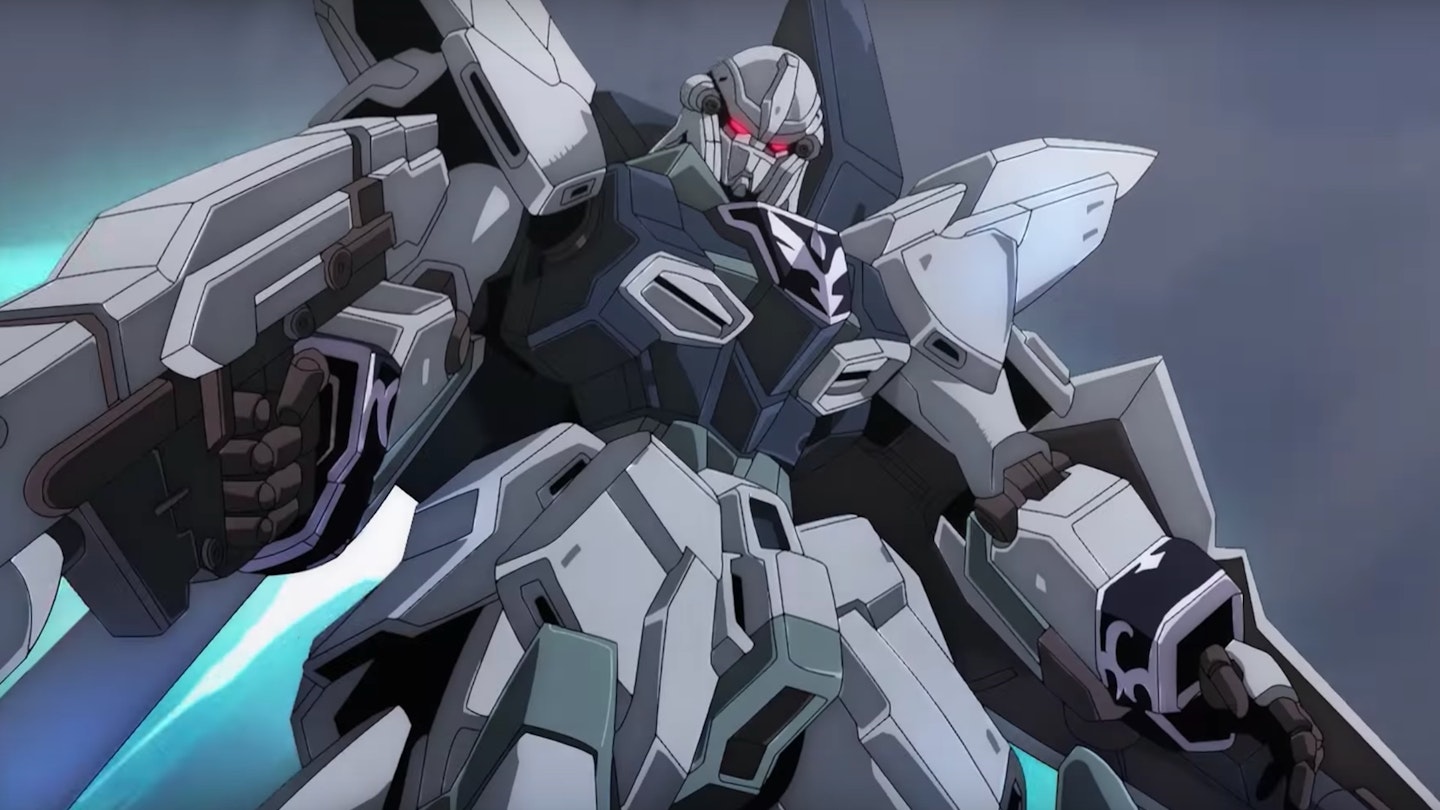

To master a Jaeger, the steeple-tall, nuclear-powered robots built to defend Earth from the Kaijus (huge monsters with fluorescent blood, enormous horned heads and the sole intention of eradicating mankind), it takes two daring pilots neurally linked via a mysterious technology known as The Drift. Indeed, before they can so much as dim the headlights on the Crimson Typhoon, Striker Eureka or Gipsy Danger, three of the pimped-up iron giants on show, the intertwined heroes must be “Drift compatible”. While it is never made entirely clear what this means (boiling down to a nebulous you-feel-me kind of thing), to enjoy Guillermo del Toro’s super-sized version of Rock ’Em Sock ’Em, it might help to be Drift compatible. In other words, get on Pacific Rim’s wavelength and there is a primal gratification in its blunt remit of very big metal things fighting very big scaly things in order to prevent an apocalypse. It’s as if del Toro has reverse-imagined his movie from how awestruck boys might stage mock-battles between toy lines. This is a spectacular brute of a film where size rather than technique matters.

In fact, the director is again mining his childhood for inspiration, tapping a vein of Japanese monsters versus robots shows, like Ultraman and The Space Giants, imported on the cheap to pick up the slack on Mexican TV. The DNA of their older brother, Godzilla, is self-evident, but del Toro would insist his new film also splices in the genealogy of mythical sea creatures and Goya’s unearthly masterpiece The Colossus. The marketing department, well out of earshot, might add the visceral mechanics of the Transformers movies, and all the hi-tech hurly-burly of videogames.

Lumbering automaton-Stallones and mechanised-Schwarzeneggers (with heaving chests and tiny heads), 25 storeys tall, the Jaegers essentially wrestle their awful foes (another Mexican thing?) — although they also boast retractable swords and spinning saws — in a succession of massive scraps. The putative plot has the robots battering their way towards the glowing deep-sea rift to slam it shut.

This primitive dynamic, however ludicrous (what about hurling big missiles from a safe distance?), provides a physical rush made doubly vivid by the unsteadying effect of 3D. But like many sci-fi visions liberated by CG, the geography of destruction is hard to follow. You get a barrage of sensation, scaled against crumbling cityscapes, but are left guessing how one battle is won and another lost. Within their cockpit heads, the two heroes enact hooks and jabs like deranged puppeteers.

These humans rarely rise above the risible. As thinly drawn as their teatime-TV ancestors, they are heroes as mechanical as the robots, pre-programmed with personal issues (chiefly dead relatives), too easily overcome. The performances get no further than their overcharged names: Charlie Hunnam is gravel-voiced maverick Raleigh Becket; Rinko Kikuchi his troubled, greenhorn co-pilot Mako Mori; while Idris Elba, as the unit’s commander Stacker Pentecost, stomps out dialogue so wooden and portentous, you fear the apocalypse may be over by the time he’s finished.

If you come to this movie seeking the dreamy Gothic play and human passions of del Toro’s corpus, you will be confounded. Perhaps, after years stalled on The Hobbit and At The Mountains Of Madness, he just needed to get a film under his belt, and the juvenile exuberance of the opportunity swept him along. The film isn’t entirely bereft of the director’s hallmarks. The Jaeger depot, located in a neon-soaked Hong Kong, is a cavernous citadel mixing hi-tech gizmos with vast clockwork apparatus; surely designs once meant for the dwarvish forges of The Hobbit. Lucky charm Ron Perlman makes us all nostalgic for the swampy superhero subversion of Hellboy as a surly, one-eyed black-market dealer in Kaiju body parts (their bone dust makes a powerful aphrodisiac). And in the sight of a prostate Jaeger washed up on a snowy beach like a fallen Titan from Greek myth, you catch a glimpse of that other del Toro, the artist still linked and compatible.

Could audiences be suffering cataclysm fatigue? Exhausted by the thought of another city pulverised like pie crust — Pacific Rim’s street fights the size of streets arrive after an unending parade of city-smashing antics this summer. Possibly, but this is a cheekier brand of Armageddon — del Toro is giving scope to a boyhood lust for mayhem, the multi-million-dollar equivalent of kicking over sandcastles and torturing insects. There is something infectiously juvenile in that. Catch his Drift and you’ll have a brawl.