There are many sides to any story, we are told. Maleficent suggests that the version of events in Disney’s 1959 Sleeping Beauty was a load of slanderous cobblers, besmirching a fairy just for having the temerity to possess a strong will, goat-like horns and a wish to put an infant in a coma. Maleficent was not, this story claims, an evil witch but a misunderstood woman, heartbroken, lonely and mostly very boring. Here, then, is the truth that gets in the way of a good story.

The opening pages take us to a land separated into two parts: one half housing humans, the other home to magical folk, among them four fairies. Three of these are your typical dainty wand-wavers, while one, Maleficent, has eagle wings and devil spikes but a good heart. She gives that heart to the wrong man and blah de blah winds up swearing vengeance on his first born, Aurora, in a repeat of the most famous scene from the cartoon.

At Aurora’s christening, two of the good fairies give her the gifts of beauty and unshakeable cheerfulness, before Maleficent huffs in and delivers her oddly specific present of a “sleep like death” when Aurora pricks her finger on a spinning wheel on her 16th birthday. We never learn what the third good fairy bestowed but we might deduce from the teenage princess’s credulous dimness that her final prize was never to be troubled by complex thought. The girl is a moron, repeatedly giggling into the path of probable death. It’s miraculous she survives to see sixteen.

There is unassailable confusion at the centre of this film. This is not a story of a woman’s fall to villainy, because it is constantly repeated that Maleficent is essentially good and won’t harm the child – minutes after giving the baby a death sentence, she’s feeding it when Aurora’s fairy godmothers don’t bother. So it’s not another side of the Sleeping Beauty tale; it’s a completely different story with the same cast and a couple of familiar moments. If the pleasure of these things is in seeing warped parallels with the original story then what’s the point if there are none and it arrives at a completely contradictory ending? It just doesn’t cohere to its simple conceit.

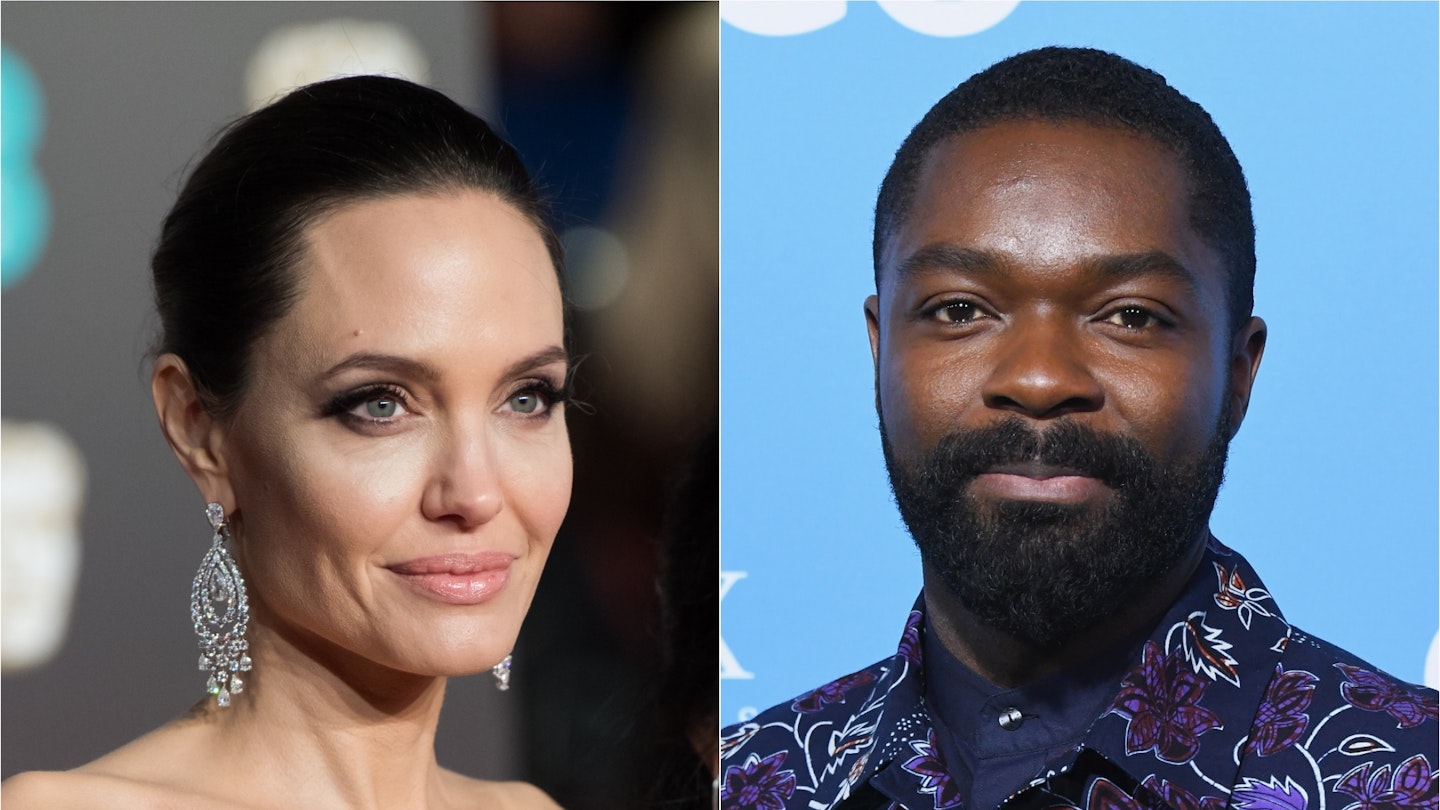

Robert Stromberg, graduating from visual effects supervisor to director, directs like a visual effects supervisor. Enormous care is taken on the magical environments, which have the same shiny box-fresh lifelessness of Oz: The Great and Powerful and Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland, and very little expended on the real people. His mood is murky and his characters equally so. You might imagine that a character like Maleficent, whose animated persona was equal parts Norma Desmond and goth drag queen, would be fizzing with acid bon mots. Not a bit of it. She gets not one funny line. She gets three funny looks, which Angelina Jolie squeezes for all they are worth, perhaps just to have something to do other than sulk in trees. Jolie is perfect casting for a flesh-and-blood Maleficent, but she’s given a costume, not a role.

Robbed of her villainy, Maleficent has become – honestly no pun intended – a Magwitch figure, lurking nearby throughout Aurora’s life and trying to keep her from harm, despite being the one who set that harm in motion. She is baffling and boring. In the move to three-dimensions, Disney has flattened the poor woman out.