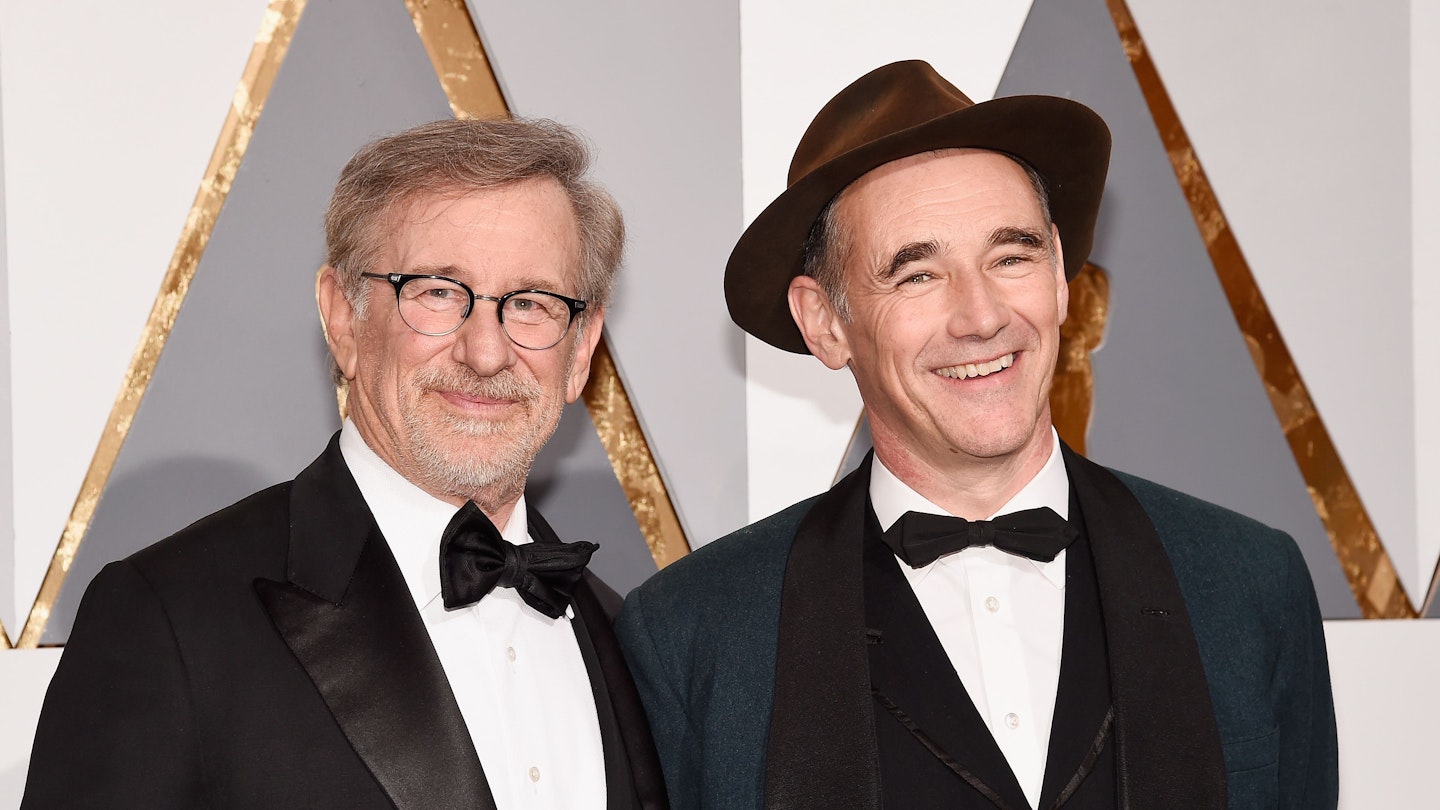

Give a director a President, and you’ll get something of the filmmaker in return. Oliver Stone brewed paranoid tempests out of Nixon and JFK, and made wry fun of Dubya in W. Steven Spielberg, with his long-mooted look at the 16th and most hallowed of American Presidents, shows us the instinctive showman and restrained thinker. He and Abraham Lincoln have a lot in common.

With Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Obama-endorsed biography Team Of Rivals as his font, playwright Tony Kushner fashioned a 550-page script of Lincoln’s political life, only for his director to lop off the last 80 pages and narrow his aim. That decision is amongst the most inspired of Spielberg’s career — ditch the biopic’s hoary formula and encounter the man at the furnace door of crisis.

So no dirt-poor Kentucky childhood. No rise to greatness. No Gettysburg Address. And only isolated dispatches from the Civil War. The trappings of family occupy subplots where his eldest son Robert (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) rages to enlist — his father wants to shield him even as he sacrifices countless unknown sons — and his unstable wife Mary (Sally Field) exhausts him with her headaches and heartbreak, even as she turns a Rottweiler’s frown upon her husband’s opponents.

This is a film dedicated to the heated final months of Lincoln’s second term. Specifically, his attempts to get the 13th Amendment, banning slavery, passed by the House Of Representatives. And if that sounds dry and talky, it couldn’t be more thrilling... and talky. Lincoln knew the soul of a nation was at stake, and, unthinkably, dared to obstruct peace in the Civil War to get the bill passed.

In Kushner’s intricate script is a clinical understanding that if the bill was delayed in order for the South to return to the Union it might never be passed — slavery would continue. This, then, is a song to democracy at its most valuable: the biography of a political moment. Spielberg demands your concentration, but his film is not a slog; it is compelling, full of beauty, and overflowing with personality.

Thought has been placed into every line and shot, a fluid marriage of image and word where the camera speaks and the language springs to life. Much has been made of how restrained Spielberg is in his direction, but that belies the elaborate framing and the coffee-dark richness of design; how the light comes thickened with dust and tobacco smoke as if it somehow has substance. And the drawing of strident performances from the massive supporting cast.

To achieve his goal, Lincoln would use every means at his disposal: argument, persuasion, threat, bribery, a ready supply of salty parables, and in one sensational scene, sat about a smoke-shrouded table with his nettlesome cabinet, the exercise of titanic will. “I am clothed in awesome power,” Daniel Day-Lewis rails, his hand slamming the tabletop as passions well up. By fair means or foul, he will sway those wavering votes in the House where, in 1865, the persuasions of Democrat and Republican were the reverse of today.

Rather than buff up the legend, already carved into Mount Rushmore, Spielberg scrapes the surface to uncover a rough-hewn practicality. Idealism needs to twist a few arms, to wheedle, to get its way. Honest Abe could be a devious so-and-so.

Lincoln is often very funny. In near-slapstick mode, three oily operatives, led by a bounteously moustachioed and profane James Spader, are dispatched to romance or bully the inbetweeners. And no-one is having as much fun as Tommy Lee Jones, his face as immobile as a cliffside as the great Thaddeus Stevens, the radical emancipator convinced to set aside his all-or-nothing convictions. In “full froth” Stevens could reduce rivals to quivering wrecks, something noted of Mr. Jones by quivering interviewers.

Of anything, you catch a scent of the Coen brothers. Here is a meticulous American milieu where obstinate men with crazy facial hair hurl insults at one another in a baroque compendium of Twainian whimsy, Shakespearean oratory, Biblical commandment and the florid spin doctoring of the day, including the single greatest use of the word “nincompoop” in cinema history. Kushner nudges his director into satire, for what are politicians if not actors? What is the House if not a theatre? But the gravity is never in question. In a glimpse of a world beyond lamp-lit Washington, Lincoln inspects the devastation of Petersburg from horseback, a bitter panorama of violated bodies: there can be savage wrongs in doing the right thing.

Perhaps fittingly, the Anglo-Irish Day-Lewis has come to represent the schizoid heart of American history: as pioneer Hawkeye in The Last Of The Mohicans; wicked, flag-draped hood Butcher Bill in Gangs Of New York; soulless tycoon Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood; and now tin-voiced emancipator Lincoln. A peerless researcher, he stoops his neck and stiffens his limbs to create Lincoln’s reputedly wooden gait, as ungainly as RoboCop. His voice is wry and reedy and takes getting used to. He is a ruminative, elusive, half-smiling presence dressed like an undertaker, given to quoting Euclid and Hamlet at the drop of a stovepipe, and Spielberg veils him in shadow and crowns him in silvery halos. It is a shame the final, unnecessary five minutes feel the need to hastily re-sanctify Lincoln for a melodramatic sign-off, for this is a micro-study in restraint: the neat concentration of a staggering man, and Day-Lewis maintains a tantalising balancing act between flesh and marble. Our first sight of him finds Lincoln with his back to us, sitting before a bandstand, an echo of the memorial to come, listening as black soldiers pointedly recite his Gettysburg lines back to him — the message is radiantly clear: live up to your words.