One of the great joys for any reader delving into James Ellroy's unofficially labelled "LA Quartet", was not only discovering the only truly epic work in modern crime fiction, but revelling in the author's use of language. By the third of these novels LA Confidential

Ellroy had reduced both dialogue, and exposition down to an instantly accessible, visceral staccato beat. By the fourth

White Jazz he'd practically given up on sentences altogether, but still managed to drag you head first into these tales of personal morality and municipal growth.

The great irony is the fact that Ellroy's unique literary style stemmed not from some great pre-determined ambition to deconstruct the language of Chandler et al, but from the fact that when he delivered the manuscript for LA Confidential, he was 100 pages over length. Rather than pick away at his incredibly intricate plotting, that mixed fucked-up fictional archetypes with even more fucked-up non-fictional figures from LA's shady history, he decided to deconstruct his sentences. The plot remained the same, who needs the odd adverb here and there?

Given that the resultant text, hugely acclaimed on its publication in 1990, still clocked in just south of 500 pages, could any filmmaker even begin to attempt to do it justice?

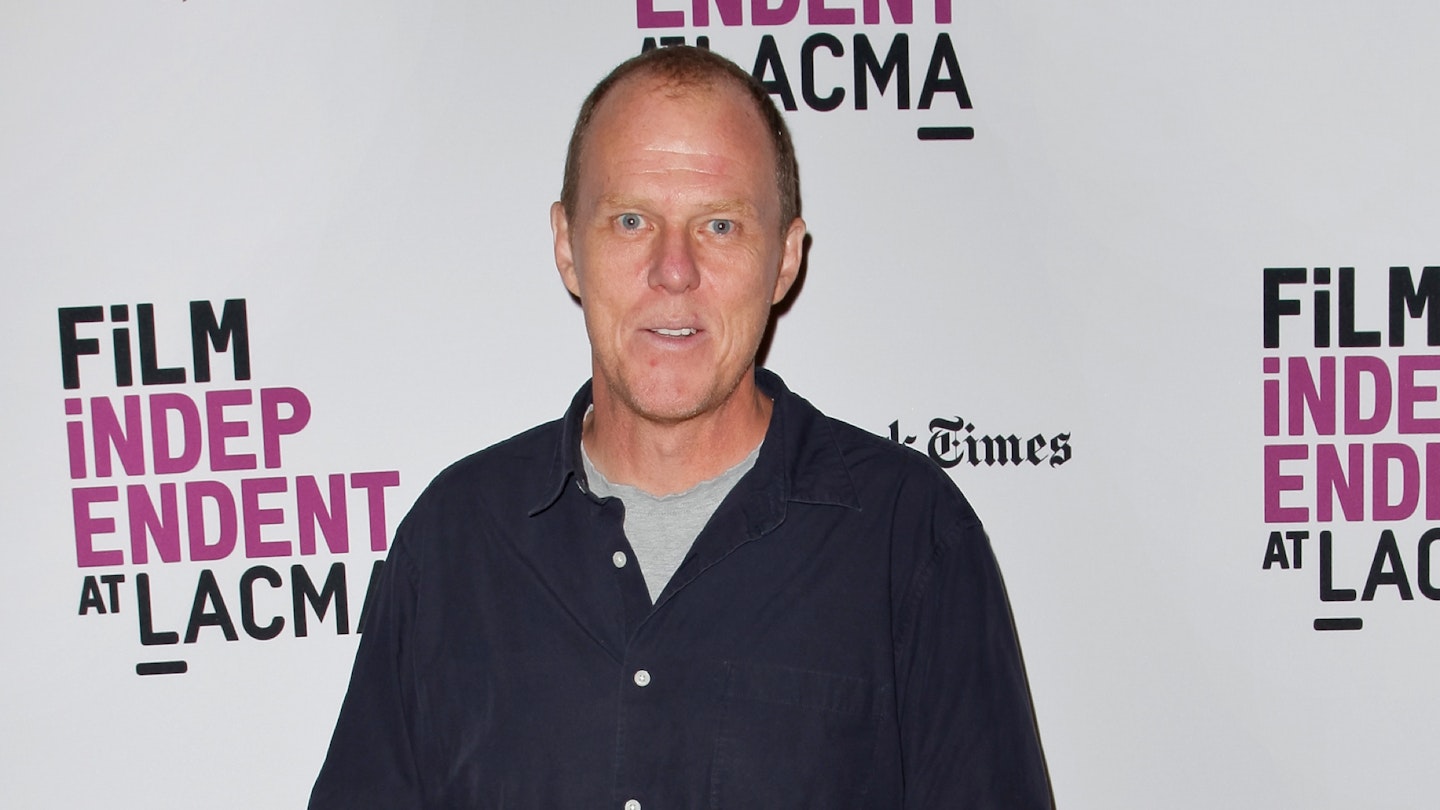

By the mid-1990s, Curtis Hanson had established himself as a decent enough journeyman director who had delivered three variations on the middle class/yuppie invasion movie Bad Influence, The Hand That Rocks The Cradle and The River Wild. Yet somehow, alongside screenwriter Brian Helgeland, Hanson found the means to take Ellroy's noir world of underclass LA to the big screen.

More than anything of course, Ellroy's quartet owed a debt to Chinatown. Both look at the evolution of the city through a kaleidoscope of social types, essentially detailing how Los Angeles came into being at the expense of the ethnic working classes, and how crime in the ghetto became a matter of economic growth contributed to as much by the upper classes as those trapped by the cycle of poverty and crime. The story of LA is the story of a city of angels who have literally fallen. Hanson intuitively knew this.

"I've always wanted to deal with a city that has a manufactured image in the first place, an image that was sent out over the airwaves to get everybody to come there, as in the main title sequence," he said. "The truth of that image was literally being destroyed to make way for all the people that were coming there looking for it. It was being bulldozed into oblivion. It's without a doubt my most personal movie."

Hanson took Ellroy's three-pronged approach, using the LAPD as a backdrop to explore the nature of personal versus

societal morality. Thus, we see three crime fighters, each with their own agenda Bud White (Crowe), a violent brute of a man, driven to avenge the violence he saw perpetrated on his own mother by protecting every damaged woman he comes into contact with; Ed Exley (Pearce), abused in subtler, more understated ways by the legacy of his father, to the point where the morality he clings to seems to have no home within himself; and finally Jack Vincennes. Ellroy himself best summed up Spacey's portrayal of this character: "It's some of the best self-loathing I've ever seen on screen." Hanson's film is a complex dive into Ellroy's world, replete with fine performances from the Oscar-winning Kim Basinger as Veronica Lake-a-like Lynn Bracken, and the estimably slimy Danny DeVito as the reporter for whom everything is, "Off the record, on the QT and very hush-hush." Dante Spinotti's evocation of 1950s' LA by night and by day is a delight, and Jerry Goldsmith delivers what is probably his best score since, well, Chinatown.

It took seven drafts of the screenplay before Hanson showed it to Ellroy. The author had some initial misgivings, and for any Ellroy purist there are things wrong with the movie Exley should never be played as a hero (despite fine work from Pearce), he's too morally ambivalent for that, and Dudley Smith shouldn't die at the end evil always survives, especially when it's presented in such an obsequious form as James Cromwell (Babe's dad!). But Hollywood has a need for black and white, while pulp fiction finds its metier in the grey and the dark, and one can accept these things. After all, Ellroy does: "Hanson proved me wrong on a | couple of things. When I read the script, I thought the shoot-out (the adrenaline-packed finale) was preposterous. And you know what? In the movie it's preposterous. Two guys holed up in a room where they kill 15 guys it's bullshit. But you know what? It's inspired bullshit."