By now, you’d think that we’d have become accustomed to Quentin Tarantino pulling the rug out from under our feet. After all, this is the man who made his name with a heist flick that didn’t actually have a heist in it.

Yet within the first five minutes of Inglourious Basterds, it’s clear that he’s done it again. Tarantino’s been talking about his World War II action movie for nigh on a decade now, but the reality is very different from the rootin’, tootin’, cigar-chompin’ Where Eagles Dare/Dirty Dozen-style shoot-’em-up that had once, if you believe all you read, been tailored for Arnie and Sly. But as the movie unfolds with a 20-minute conversation between a French farmer who may or may not be sheltering Jews, and Col. Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz), a charming yet callous Nazi officer nicknamed ‘The Jew Hunter’, it becomes quickly apparent that Tarantino’s flipped a bloody middle finger at convention.

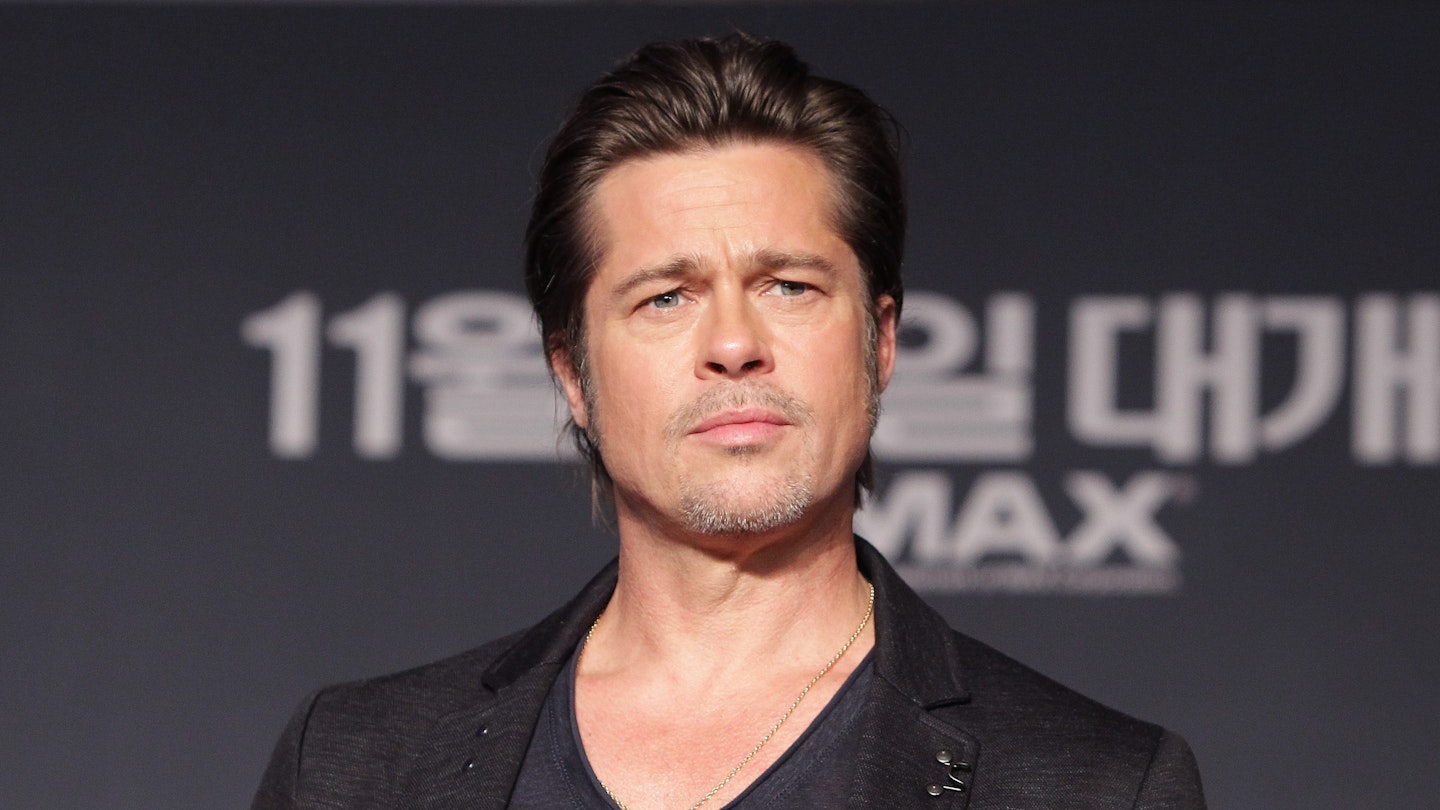

Yet that’s Inglourious Basterds all over. As enjoyably idiosyncratic as the spelling of its title would suggest, it’s a film that takes devilish delight in feinting left when it looks like it might go right. Characters are introduced, pomped and circumstanced, and then almost glibly despatched; the Basterds themselves barely appear, while Brad Pitt, the ostensible lead, shows up for only three of the movie’s five chapters and doesn’t fire a single shot in anger; while history is adhered to with all the accuracy of an MP’s expenses claim.

As ever with Tarantino, Inglourious Basterds reveals a director in love with the sound of his characters’ voices — sometimes to a fault, as in the third chapter, German Night In Paris, which is packed with dense conversations at the expense of dramatic momentum. But, after the self-indulgent riffing of Death Proof, Inglourious Basterds is focused and sharp.

Take that opening scene, for example, in which Landa toys with his prey like, to use his own analogy, a hawk with a rat. Or, more pertinently, the lengthy fourth chapter scene set in a French bar, La Louisiane, in which British officer Archie Hicox (Michael Fassbender), two Basterds and German double-agent Bridget von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger) have to outwit a suspicious Gestapo officer (August Diehl).

In both these scenes, Tarantino masterfully transfers control from character to character, using only his dialogue, filled with unspoken implications and threatening subtext. The results are almost unbearably tense and as suspenseful as anything he’s done in his career. Never mind big bangs and blazing machine guns — in a Tarantino film, this is where the action is.

And his cast, from Pitt down, responds in kind, whether they’re handling the one-liners or speeches in English, French, German or even Italian. There are standouts, of course. Pitt, in a role that again defies expectations, is often hilarious, attacking some wonderful dialogue in a thick-as-molasses Kentucky accent that itself might require subtitles from time to time. Fassbender, stepping into the role of Hicox after Simon Pegg dropped out, seizes the opportunity gladly, injecting Hicox with the perfect blend of old-style movie-star charm (the character was based in part on George Sanders) and a tougher, rugged edge that deserves to make him a bigger star. But the film belongs to Waltz, who won the Best Actor award in Cannes, and who should be a shoo-in, even this far out, for a Best Supporting Actor nod at next year's Oscars.

The role of Landa was so tough to fill that Tarantino claims he'd have abandoned the production entirely had Christoph not Waltzed through his door. Not only is Landa multilingual, but he's an enormously complex creation, so much more than a typical movie Nazi. Cruel, confident, calculating and often contradictory (watch how his attitude towards his Jew Hunter nickname changes, depending on the company he keeps), Landa has many of the film's best lines and moments, and is much-missed when he's not around. Thankfully, Tarantino - perhaps sensing that he was onto a good thing - keeps that state of affairs to a minimum.

And all throughout it, like Pitt's Raine, Landa is very funny, a charming and somewhat effete presence who delights in his grasp of other cultures ("That's a bingo!") and his destabilising effect on others. And that's another surprising element here - Inglourious Basterds is often very funny. In fact, as the movie races towards its climax, it gets funnier and funnier even as characters start hitting the ground like flies. And the ending itself is so bold and so outrageous that it's hard not to laugh at Tarantino's audacity.

In Cannes, the movie's climax split critics, with some offended by Tarantino's contrivances. But the big clue here lies in the opening title card, which simply states, "Once Upon A Time...in Nazi-Occupied France."

From the off, with that one phrase, Tarantino makes it clear that Inglourious Basterds will not be taking the austere, reverent approach of a Schindler's List. Instead, this is a fairy tale, a 'what if...?' story that takes place in a typically Tarantino 'movie-movie' universe. After all, let's not forget that Tarantino had Uma Thurman draw a box on the screen in Pulp Fiction, and that Basterds is replete with those touches, from on-screen graphics to a wonderfully eclectic soundtrack that revels in anachronisms like Bowie's Cat People (Putting Out Fire).

That song, like every other piece of music in the film, is taken from another movie, with Ennio Morricone and Dimitri Tiomkin cuts featuring prominently. Of course, that's not entirely unusual - after all, Tarantino is a movie magpie, and his work has always been informed by the tropes and iconography of other movies. Basterds, for example, is full of references to Italian cinema, particularly Spaghetti Westerns, while there's an element of cheekiness about his decision to cast Mike Myers as an English general with more than a hint of Austin Powers about him.

Ultimately, though, it's about the appeal and power of cinema to do good, to shape history, to change things for the better as Tarantino pits the forces of good - including a film critic, a cinema owner and a movie star - against the vile Nazi propagandist, Joseph Goebbels, and his new protege, Frederick Zoller (Daniel Bruhl). And as events play themselves out, amidst scenes of fire, chaos, carnage and a haunting image of a laughing face projected onto roiling clouds of smoke, it's hard not to imagine Tarantino sighing contentedly as he introduces his final, most romantic notion: a director playing God.