Trainspotting, Danny Boyle's generation-defining adaptation of Irvine Welsh's cult novel, just turned 25 – and it remains a landmark British film, packed with iconic images, characters, and scenes that left an indelible mark on the medium. Across two-and-a-half decades, it catapulted its director and stars to greater heights, spawned belated sequel T2 Trainspotting, and remains one of the most important films of the 1990s. Originally published in March 1996, in issue #81, Empire presents the full story of Trainspotting's creation from behind-the-scenes accounts at the time, right back to the script stage, up to its eventual release. Choose to read it here:

You're a director/producer/writer team trying to carve a niche for yourselves in the British Film Industry. You make a modest little thriller, filmed in Glasgow in 30 days and starring a trio of relatively unknown actors. You decide to call it Shallow Grave. It receives astonishing reviews, and earns more than £5 million on its home turf, making it the biggest home grown film of the year.

Suddenly, the limelight beckons. Everybody loves you. You're pronounced British Film Industry saviours, are compared to everybody from Hitchcock to Tarantino, scripts pour through your letterbox at an alarming rate, and the phone rings off the hook. Movie folk from across the pond deluge you with six-figure offers just to say yes to their next project. You have, in a very real sense, arrived. There's just one small problem: how do you follow it up?

In the case of Danny Boyle, Andrew MacDonald and John Hodge, the directing/producing/writing trio behind 1994’s hit Shallow Grave - you shun the overseas hotline, take £1.5 million and some up-and-coming talent, and head back north of the border to film Irvine Welsh's cult Scottish novel Trainspotting, a series of vignettes concentrating on heroin-hooked anti-hero Mark Renton and his attempts to kick the habit, despite a lack of cooperation from his similarly-inclined friends.

The result is an electric combination of hilarity, razor-sharp irony and the harrowing effects of drugs on a life. It is, in a word, brilliant. And this, from the proverbial handshake over the book rights, to the point when the rest of the world discovers just what all the fuss is about, is how it came to be...

December 1994

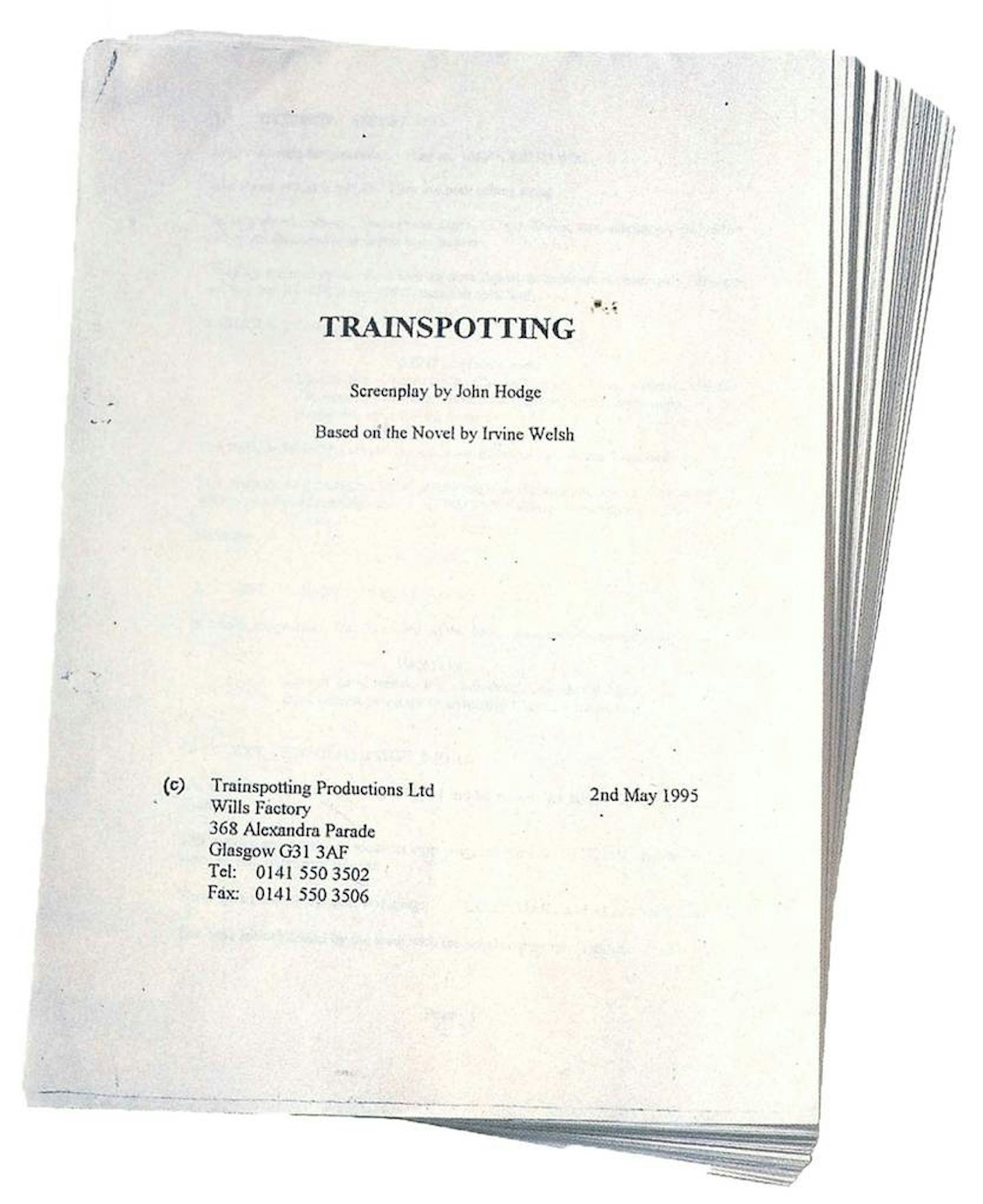

If you're planning to translate a novel into movie form, the most important thing, obviously, is to snap up the screen rights. However, while John Hodge starts to bash out the first draft of Trainspotting's screenplay, producer Andrew MacDonald and director Danny Boyle are caught up in what will prove to be the only crisis of the entire project - securing the rights to Welsh's book.

One of the key issues was not to make a film that cost a lot of money.

"The problem," laments MacDonald, "is that we can't directly buy them from the book publishers (Minerva) because they've been sold to Noel Gay (TV production company responsible for Red Dwarf). They don't have plans of their own to film Trainspotting, but, as soon as they sniffed that something was up, they wanted to be co-producers - and we weren't keen on that. But, of course, we're desperate to get the rights." Hodge presses on with the script, regardless.

"Irvine Welsh expressed a wish not to be involved with the writing of the screenplay," he explains. "I think he wanted to move on to other projects, which was understandable. So I went ahead and did the first draft in a few weeks." For Hodge, Trainspotting proves to be a trickier task than Shallow Grave which, being an original screenplay, allowed him entirely free rein.

"When you're adapting a book, on one hand you've got to be prepared to sacrifice things to make it more cinematic. On the other hand, if you lose too much you might as well make up your own story, because what's the point in paying for the rights? You could buy a blank page for nothing.”

“But, when you're transferring something to the screen you have to go for the visual rather than the literal. We decided to make up a few scenes, but I can justify them all by the fact that they're all taken in some way from the novel. For example, there's a shoplifting scene that doesn't actually happen in the book. But there are loads of references to it and it's a very visual thing, so it seemed right. Then again, there are lots of scenes you can really go for, like the one with the opium suppositories, or the Sunday morning breakfast sequence."

With Shallow Grave still unreleased but garnering the kind of word of mouth many major releases would kill for, the filmmaking threesome are being badgered by Hollywood mogul Scott Rudin (producer of Sabrina and The Firm), who offers them $250,000 to film whatever project they desire.

"Actually, it was just for John, only we haven't told him that," quips MacDonald. "But the offer was ridiculous. I mean, we haven't even met the guy...”

January 1995

Shallow Grave is released on January 6 to the predicted ecstatic response, and goes on to break house records at five London cinemas in its opening weekend, including the MGM Haymarket and Gate Cinema in Notting Hill. Hodge completes his first draft, and moves on to further drafts, adding "progressively fewer changes each time." The battle for the rights proves to be ongoing…

February 1995

Hodge is still hard at work and the rights are still problematic, even more so when Channel 4, which is financing the film (the first time it has covered the whole cost of a project) refuses to put up a penny until the mess is sorted. "I'm confident we'll be able to bully our way into it," says MacDonald, "because Channel 4 like the script, which is a powerful asset. And we have the author on our side. When Irvine heard about our plans, he wrote us a brilliant letter saying we were the greatest Scotsmen since Kenny Dalglish and Alex Ferguson." (Isn't Danny Boyle from Manchester? - Ed.)

Boyle remains equally optimistic. "Another factor," he points out confidently, "is that only someone like Emma Thompson or ourselves, with a track record in British films, would be able to make a film like this, because of its subject matter…”

March/April 1995

Much to everyone's relief, the rights problem is finally ironed out with the deal eventually being done for two per cent of the film's budget, and Noel Gay backing out of hands-on duties in exchange for a share of the profits and a name check on the credits. Channel 4 stumps up a budget of £1.5 million - only £500,000 more than Shallow Grave.

"One of the key issues," clarifies Boyle, "was not to make a film that cost a lot of money. You can get carried away with people offering you money and end up making a film that's out of proportion with your kind of audience. But, on the other hand, we couldn't make it for £1 million, so it's gone up." In the meantime, pre-production starts in earnest.

Jonny just walked in and he was Sick Boy straight away. He was lolling about in his chair right in front of us.

"This is what's known as the run-up period to the film," Boyle explains. "It lasts for four to seven weeks depending on your budget (Trainspotting's is seven) and takes in casting, location scouting, working with the art department on the look of the film - for something as simple as colour, or the way something looks when it's shot - costumes. Right now, all the different departments are coming onboard.”

First and foremost, however, is the casting. Ewan McGregor, who played Alex in Shallow Grave, is earmarked for the Renton role from the start, and is first onboard. Elsewhere, there is careful discussion with casting directors Gail Stevens and Andy Pryor, although this proves to be relatively uncomplicated.

"We sit down and make a list of the top talent," explains Boyle, "and we see a lot of actors, quite a few who we recognised from casting Shallow Grave. But for some of the parts, we knew who we wanted - people like Ewen Bremner (who eventually plays the part of Spud) and Bobby Carlyle (Begbie).

"We wondered whether they would consider playing parts that were beneath them, especially Ewen Bremner (who at this stage is starring as Renton in the stage version of Trainspotting at London's Bush Theatre), but getting them to agree to play Spud and Begbie is a huge boost, especially when they have all sorts of reasons why they could turn it down."

Next to pop out of the woodwork is Kevin McKidd who is cast as Tommy. A relative newcomer, hogging the camera in Gilles McKinnon's Glasgow allegory Small Faces, he is described by Boyle as "like meeting one of the Beach Boys at the height of their fame - the perfect picture of innocence."

Jonny Lee Miller proves to be another who fits the part perfectly. "He just walked in and he was Sick Boy straight away," confirms Boyle, "he was lolling about in his chair right in front of us.“

May 1995

The script's ending is still up in the air, with MacDonald, now ensconced in Glasgow, and Hodge, in London, in constant phone contact. The original finale, which allows for a kinder, more optimistic denouement, is reinstated, and the final draft of the finished text is delivered just before filming starts.

Rehearsals begin the second week in May, in a rented flat at the top of a Glasgow tower block. "It's one of the tallest tower blocks in Europe," enthuses Boyle. "It'll be like being at the top of an aeroplane. We try to get the leads, but you don't need all the actors for rehearsals because quite a lot of them are only doing one or two days' filming."

As with Shallow Grave, Trainspotting is set in Edinburgh but filmed mostly in Glasgow. "The Glasgow Film Fund were heavily involved on Shallow Grave," explains Boyle, "which means you have to do as much of your filming as you can in Glasgow. Also, ironically, a lot of the top film crews in Britain live here. But we're doing a couple of days in Edinburgh and also pick-ups (scene-setting, dialogue-free snatches shot to pad out the action)."

Meanwhile, a crew has been assembled, and consists mostly of people who worked on Shallow Grave. Led by Boyle, they are midway through a recce, hunting for suitable locations in which to film exterior scenes. The activity on this particular day involves darting around Glasgow. Having completed a trip to a crematorium in the morning, everybody reconvenes for lunch at the Brewhouse in the town centre. Coincidentally, this bar, complete with ample balcony area and quiet coves aplenty is also the next stop on the location list.

Courtrooms tend to be reluctant to let film crews in because, I don't know, Taggart misbehaved or something.

Tomorrow it's off to Edinburgh to explore the possibilities of filming a shoplifting scene in John Menzies, in the city's Princes Street. The Scottish newsagents stepped into the breach after another major retailer pulled out due to the subject matter of the scene in question. However, today, MacDonald is not feeling too well, suffering from a decidedly dicky stomach that he blames on a sausage roll of dubious origin. So he heads back to the production office, based at the disused Wills cigarette factory on the outskirts of central Glasgow, while Boyle and his cohorts suss out the bar.

While a recce, to the outsider, appears to be little more than a load of people standing around looking at their surroundings, the technicalities go a lot deeper. In the Brewhouse, for instance, the prospective location for Day 14's scene in which Begbie starts a major bar-room brawl, the initial concerns are that the lightbulbs are too bright and that an unstrategically placed spotlight could hamper filming. "Also, we might have a problem doing a panning shot across the bar," muses Boyle, "we might need to add more chairs and tables."

With the bar already equipped with booths, Boyle and production designer Kave Quinn conclude that the bar can be refitted with a long table and bench, as well as a balsawood chair needed for the fight scene. It is also decided that around 90 extras will be needed for the scene, ten of them for the punch-up. To keep costs down, only one section of the bar will be used, filled with tables to give the impression that it is more thickly populated. The lightbulbs will be replaced.

"The cost of this place will depend largely on the relationship with the brewery," explains Boyle. "It depends how much they want us here, and how much business they'll lose as a result - one day's shooting is 8am till 8pm. I'd say it'll cost around £500-£1,000 for one day's filming.”

"But this is the only chance we really get to examine everything," he adds. "There are so many different things you have to take into consideration. You have to balance up the colour of the place, the temperature, and then brief the location manager about things you need. The Brewhouse, for example, is the only pub we could find with the necessary balcony. We had difficulty finding a crematorium and especially a courtroom. Courtrooms tend to be reluctant to let film crews in because... I don't know, Taggart misbehaved or something."

With the bar fully examined, everybody piles into the waiting bus to make the 15-minute trip to the next prospective location: the Volcano nightclub. The club turns out to be locked, leaving everybody to stand around for 20 minutes. Someone with a key is eventually unearthed, and once inside, Boyle explains the set-up to everybody.

"Now in this scene," he says, "there'll be crazy dancing out here, while Tommy and Spud talk about sex. over in one corner, and their girlfriends do the same in the toilet. And Renton manages to land Diane. It's basically a pick-up joint."

This time, it's fluorescent light that is required. "The place needs to be painted purple to give it a neon effect," explains Boyle. The club's name will be retained, but muslin and canvas drapes will be hung to curtain off the section where Tommy and Spud are having their conversation. Meanwhile, concern about dialogue being drowned out by loud music will be dealt with by recording speech as normal then adding subtitles.

All parties satisfied, the club, and its adjoining car park - for the scene where Renton and Diane first meet - are booked for filming on Tuesday, May 30, 1995.

Then it's into the ladies' loos to work out co-ordinates for the sex talk between the two girlfriends. Happily, the facilities prove to be the right size, the purple walls ideal. But again, lightbulbs are a problem. Covering them with black tape or removing them altogether seems to be the best option. A constant stream of extras moving in and out will add the finishing touch.

As for interior filming, the Wills factory, currently playing host to a hive of production office activity, has more than enough room within its 15,000 square feet for the sets needed for the allotted three weeks of interior filming. Not only will it double for squalid Edinburgh squats, it will also accommodate the film's more cosy, suburban aspects, and even' a couple of London sets. Exterior filming will entail a three-and-a-half day trip down south at the end of the seven-week shoot. At the moment location scouts are busily scouring London.

In addition, the winding corridors of the former cigarette factory, now decorated with an assortment of recent film posters, are housing the costume and art departments. Art is filled with storyboards detailing a frame-by-frame analysis of how each scene should look, set designs ("reference ideas and general junkie stuff," says MacDonald) and photos of "interesting" street corners in London that might make appropriate locations.

The look of the project comes courtesy of Kave Quinn. Having been responsible for the primary coloured veneer that made Shallow Grave so memorable, Quinn has once again been drafted in to work similar miracles with Trainspotting, although there's more to her job than slapping on a coat of paint.

The look of Trainspotting is drawn from real life but very much exaggerated.

"You read the script, discuss what you think about certain aspects, talk about the general look of the film, and obviously do research," she explains, "which we did by going round estates in Glasgow. The look of Trainspotting is drawn from real life but very much exaggerated. And it's quite stylised, which makes it more interesting than just documentary style.”

“After that, you start planning sets, reference photographs and sketches, passing everything to Danny so he knows what we're doing before we actually do it. He in turn passes information back to us and it's all put together. You have firm ideas about how you think things should be and hope he'll like them. Similarly, he has ideas about how he thinks it should be. "Because there are about 30 sets on this film, while one set is being used I'll be designing and dressing another, which will then be built. It's a constant production line."

Having already worked on the storyboards - scene-by-scene sketches of how each scene will look on screen - Quinn turns her attentions to props and locations. "The final thing is deciding whether to use locations or build sets, and whether the locations are good enough. Then, about six weeks before production, I start buying things that would make good props. On Shallow Grave we hired lots of props, but on Trainspotting about 98 per cent is cheap junk we bought."

Further investigation reveals a nice pile of props that includes everything from candles to spacehoppers to, bizarrely enough, a dustbin lid in the shape of a smiling frog. “I found that outside a junk shop in Glasgow. It was part of a rubbish bin," she smiles. "There were actually rubbish bins like that around Glasgow in the mid-’80s."

In the room next door, wardrobe mistress Rachael Fleming is up to her eyes in boxes and rails of clothing. However, while many costume departments will create their own outfits, most of the items on display today bear a striking resemblance to Oxfam cast-offs. "Some of the stuff is from there," Fleming admits, pointing to rails of shrunken football tops and equally restricting jeans, "but a lot of this is our own stuff from the ‘80s. North Face lent us all the equipment for the hikers in the film to use, which was brilliant. But a lot of people are reluctant to lend us stuff, because of what the film's about, I suppose."

Before filming can start, there is one final task to be fulfilled: the role of Diane (the schoolgirl who Renton sleeps with) remains uncast. In an effort to discover a fresh face for the part, cards are distributed round clubs, clothes shops and hairdressers, offering up-and-coming thesps the chance to become "the next Kate Moss or Patricia Arquette". Hundreds of hopefuls turn up to auditions and are interviewed by Boyle and MacDonald.

A shortlist of a dozen read a scene, before the part eventually goes to Kelly MacDonald (no relation). "I knew straight away before she even sat down and opened her mouth that she was the one," says Boyle. "There were a couple of other possibles, but you could just tell. And if you get that instinct, you know you're right.“

June 1995

Filming takes place during a stiflingly hot month. "Everything's going very smoothly," remarks MacDonald. "Everybody's been well; we've been pretty lucky with the weather. Channel 4 are pleased. It's all pretty exciting."

The shoot lasts for 35 days ("We only had 30 on Shallow Grave, so it's a promotion," grins Boyle), spans five days a week, give or take the odd Saturday morning, and includes a week of dreaded night shoots. "It used to seem so terribly glamorous," groans Boyle. "But the problem with night shoots at this time of year in Scotland is that the nights are so short. Daylight doesn't stop until 11 pm, and it's back again by 4.30 am, which only gives you a few hours of darkness. But then you do get more hours of daylight to work in."

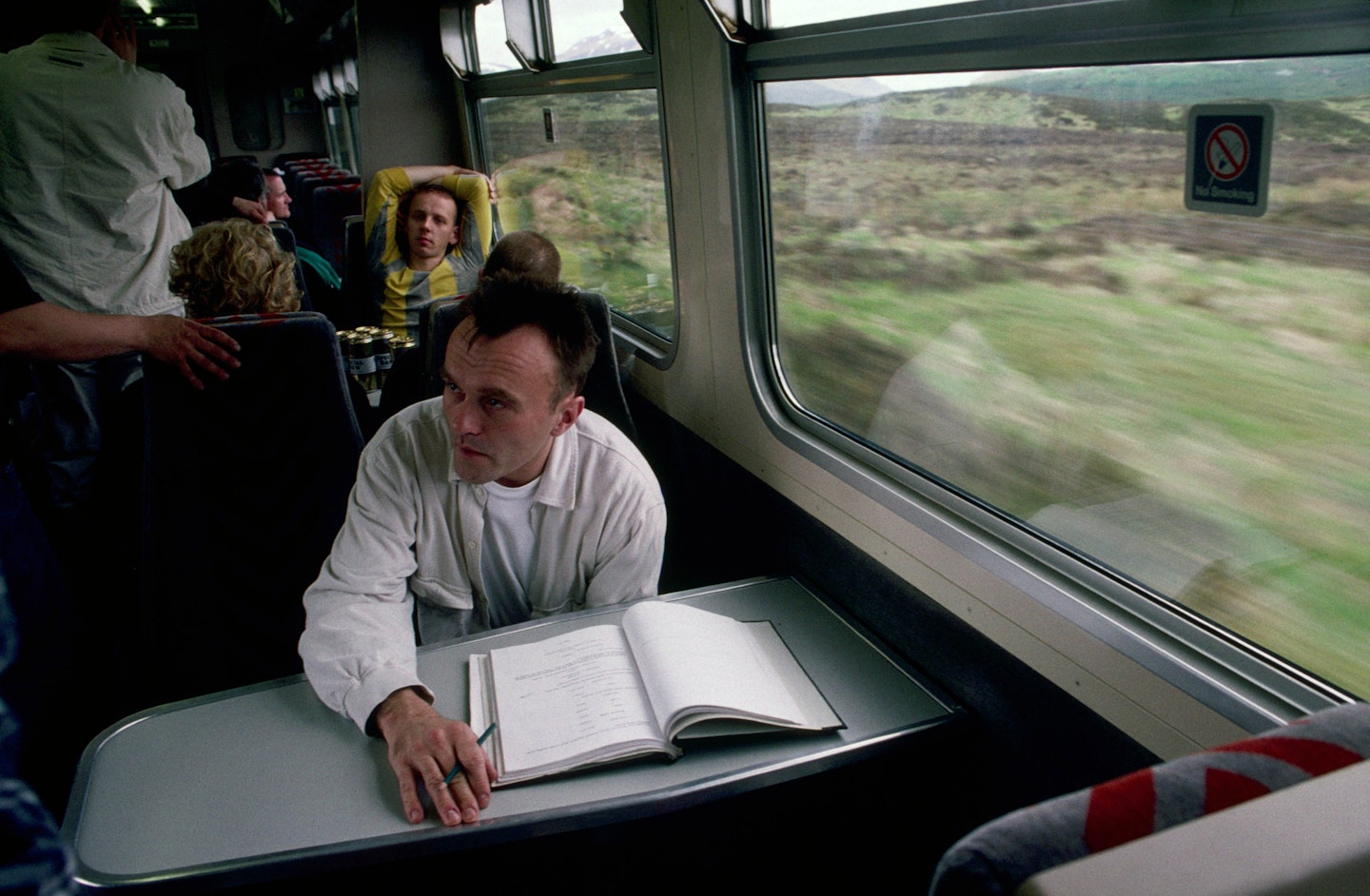

It's Day 19 that takes the crew to Edinburgh, to film the title sequence, which involves McGregor and Bremner running away from the scene of their shoplifting activities, with the authorities in hot pursuit. And if that store security guard looks familiar, it's because it's scriptwriter John Hodge, taking a break from working on the trio's next project, provisionally titled A Life Less Ordinary, and capitalising on his role as the junior police officer in Shallow Grave, by turning up in Trainspotting. "They fired him from the police force," he jokes. Hodge, incidentally, is just one of a number of behind-the-camera folk-with minor roles in the film. MacDonald plays a prospective tenant in the London scenes, while Irvine Welsh appears as Renton's drug dealer, Mikey Forrester.

McGregor is shoehorned into drainpipe jeans, shaven-headed and looking two stone lighter than usual. Although the cast are not on the near-starvation diets common among junkies, everybody has had orders to slim down. "They're not supposed to drink a lot, they just have to be sensible about it," states MacDonald.

For the best part of the morning, the actors breathlessly pound the same stretch of pavement, littering the ground with the products of their kleptomaniacal spree. Once the Princes Street scene is in the can, the crew moves to an Edinburgh back street for the next stage of the title sequence, in which Renton is hit by a passing car while fleeing the law. On the screen, the scene lasts less than five seconds, but in reality, it takes two hours to perfect, as McGregor is "run over" about 20 times and has to take numerous breaks to be patched up by the on-set nurse. The atmosphere is unsurprisingly tense.

"My biggest concern today," states MacDonald, "is finishing on time, because we've had two very long days. We travelled a long way (having filmed in the middle of nowhere the previous day and arrived back in Glasgow at 11pm), we've got to finish, get home, and start tomorrow morning at eight. That's always the biggest worry, because we have over 50 locations on this film and it's only low-budget. To go back somewhere is twice as expensive, and also we can't afford to come back to Edinburgh. Every day is full to the brim anyway."

And before the cast and crew can wrap for the day, they return to Princes Street to do an hour's worth of further pick-up shots on the opening sequence, eventually finishing at 8pm.

For most, work begins around 8.30 am after an on-set breakfast, although MacDonald and Boyle arrive 90 minutes earlier to run through the day's arrangements. MacDonald usually returns to the production office once filming begins, trekking back to the set for meal breaks and towards the end of the day to ensure that everything is going according to plan. "My job at the moment is to oversee everything - the producer shouldn't have to do too much during shooting. I'm with the photographer, talking to the distributors, working on the publicity (handled by London-based PR firm McDonald & Rutter), trying to keep a lot of agents, friends and family away from the set. Trying to appeal to everybody, which is very difficult. Everybody has their own agendas. The art director wants all the money to make the sets better, the camera wants all the lights to make them look better, the production department wants to keep all the money and get more drivers. That sort of thing."

Trainspotting is quite difficult to edit, because it doesn't have a proper narrative flow.

Boyle and MacDonald then spend the evening watching rushes of the day's filming. Although 30 to 40 minutes of film will have been captured, perhaps only three will be used. And although the editing process is a part of post-production, the film's editor Masahiro Hirakabu is already ensconced on the project. "While they're still shooting, my job is to assemble the scenes in their correct order, so that by the time filming is finished, most of them are in the right places," he explains. "Each scene obviously features lots of different shots, you just have to put them all together." At the end of the day, most of the cast and crew go to their nearby homes, although a handful are staying at a hotel for the duration.

"Most of the crew are Scottish, so they stay at home," admits MacDonald, "but most of the actors are staying in flats. It's better if you have the odd day off." More importantly, how much is everybody pocketing? "Around 700 quid a week, something like that…”

During filming, a teaser trailer is shot to raise audience awareness of the film. The 30-second clip makes its first appearance on the rental video of Shallow Grave, released in July. The proper trailer will be done at a later date by film design/merchandise experts The Creative Partnership, with Boyle and MacDonald having final approval. The teaser is subsequently cut to a 35mm format for its cinema outing, scheduled for November.

At this stage, PolyGram Filmed Entertainment (distributor of Shallow Grave in the UK - with Rank - France, Belgium, Holland and the US) buys Trainspotting's UK rights, as well as those of France, Belgium, Spain, Holland and Australia, and secures a February 1996 UK release date. PolyGram's marketing manager Julia Short brings to the set representatives from the Screen, UCI and Showcase chains, and the Gate in Notting Hill. "We saw them filming in Edinburgh," says Short, "then went round all the sets in Glasgow. Andrew showed them the first four minutes of roughly assembled footage. It makes them all feel very much involved."

July 1995

With filming completed, Boyle and Hirakabu bundle into an editing suite in London's Soho for the all-important job of cutting the film down' to its required 90-minute length, a process that in Trainspotting's case will take eight weeks to complete. "This is the point where the director comes in and looks at the film - and screams! " jokes Hirakabu. "It's always longer than you ideally want it to be, and it becomes evident that certain scenes either need to be cut down or deleted. The main thing is to look for continuity, to ensure that everything works. It's very detailed."

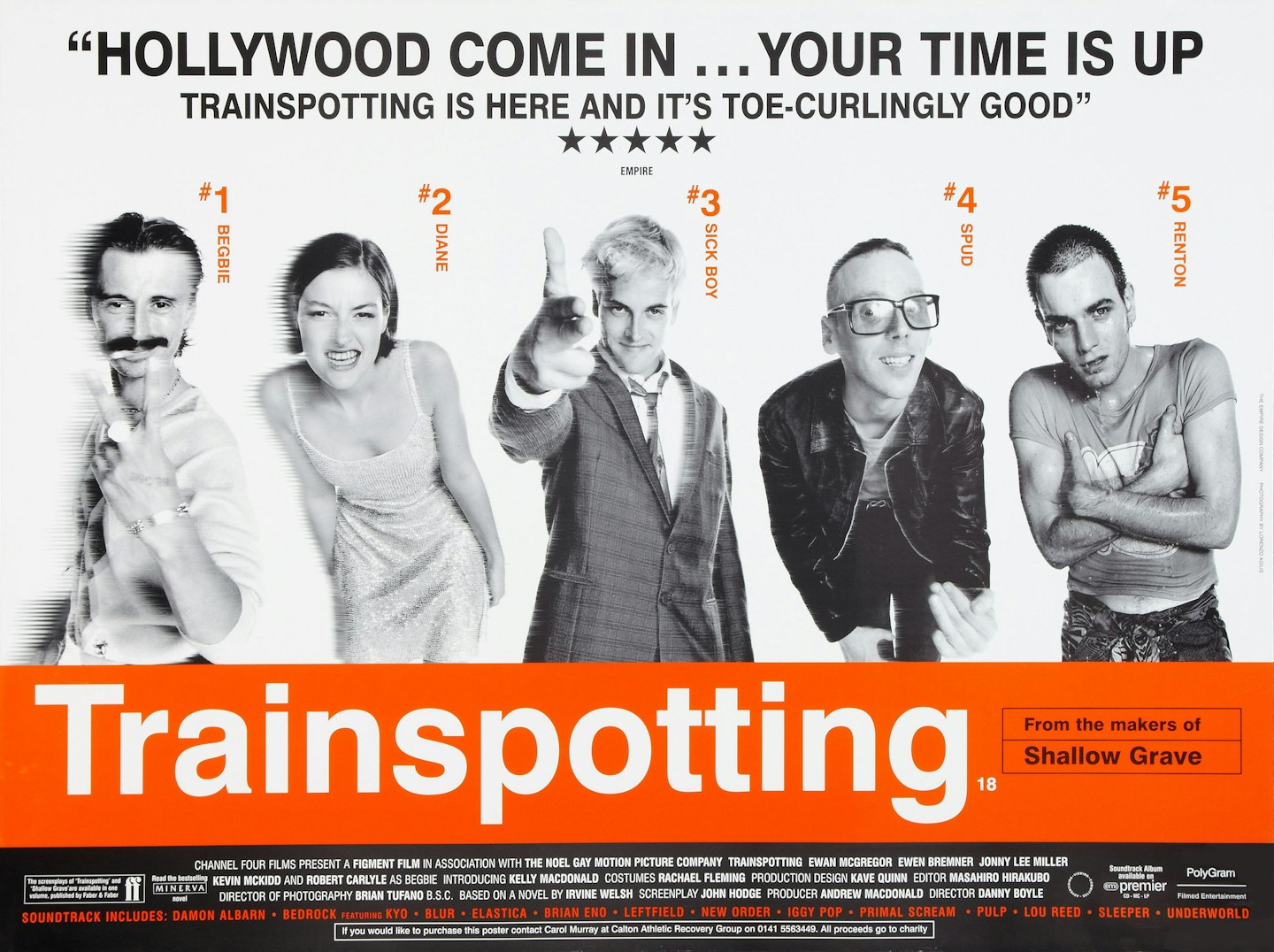

Work also begins on the film's poster, with a special photo shoot. Just hours after the final take, McGregor, Carlyle, Bremner, Miller and Kelly MacDonald are hauled into a Bayswater studio for a day's photography. The pictures are snapped by Lorenzo Agius, a photographer who has made numerous contributions to Empire in the past.

August/September 1995

Editing continues. "Trainspotting is quite a difficult project to edit," confesses Hirakabu, "because it doesn't have a proper narrative flow, which means that one scene won't necessarily relate to the next. Also, it has a lot of music scenes and voiceovers, all of which have to come together. I've been working 12-hour days on it."

A rough cut is screened for the first time to a favourable response - to Channel 4 drama head David Aukin, the man with his finger on the green light of the company's film production. And finally, after eight weeks of editing, the picture is "locked" - in other words, no further editing will be done. However, the film is still far from completion, the next stage being to knock the sound into shape. This entails adding effects and re-recording certain lines of dialogue (ADR or looping) under studio conditions if they failed to record audibly during the shoot.

"We've tried to keep as much of the original dialogue as possible and just add effects," explains MacDonald, "so that the dialogue is very raw and stylised." Still, certain aspects do need to be improved.

Ewan McGregor is drafted down to the Smoke to do his bit, as is Scottish football commentator Archie MacPherson who is squeezed into the suite for 20 minutes on a Tuesday afternoon to add some spicy, double-entendre-layered commentary to the footage of Archie Gemmel's legendary 1978 World Cup goal that is intertwined with the film's pivotal sex scene.

Meanwhile, the third, trickiest, aspect of sound editing is the one currently occupying most of MacDonald's time: the soundtrack. Having heard one confirmed track - a terrific cover version of Blondie's Atomic by indie darlings Sleeper - MacDonald plans to make Trainspotting 1996's most exciting soundtrack.

"I've been talking to bands, clearing musical tracks. We've got tracks like Lust For Life by Iggy Pop and Perfect Day by Lou Reed, and we've also got new bands like Blur, Pulp, Primal Scream, Sleeper, Leftfield and Underworld. There's about three or four new tracks. Pulp didn't have time to write a new track, so they've donated one that didn't go on their album. But the hard part is getting that balance, getting them all to agree to do tracks for what is only a £1.5 million film."

Additionally, the design for the teaser poster is now complete and is forming part of a Student Railcard promotion whereby college types buying a railcard get a voucher they can exchange at HMV in Edinburgh or fresher’s fairs up and down the country for one of eight posters - including the Trainspotting teaser.

October 1995

The remainder of the music tracks are cleared for use and looping continues. "When we did Archie MacPherson's bit we had to get the rest of the sound together," informs MacDonald, "which we've spent two weeks doing at a new theatre at Shepperton Studios Ridley Scott has built. After that the negative is cut and the prints start to get made."

The roughly assembled film is shown to PolyGram for the first time. Also present are a number of cinema exhibitors. "They're the most important people," explains MacDonald, "because we want to open it when we are ready. I think it's worked out – we've got our ideal line-up of cinemas." The first showing of the completed film is scheduled for November 13.

November 1995

The teaser trailer makes its debut in cinemas, while the November 13 screening is for a few select members of the press (including Empire) and people involved in the making of the movie. Even Blur's Damon Albarn turns up. But how well was it received? "My father went to the screening," reveals MacDonald. "He's pretty honest about these things, and he really liked it, which surprised him. So that was very encouraging, but on the whole it's difficult to tell till the film opens…”

At this stage PolyGram's marketing department comes on board. Having received the finished print, the film is dispatched to the British Board Of Film Classification (the BBFC) for certification - in the same week that teenager Leah Betts tragically dies after taking Ecstasy at her 18th birthday party. The film receives an 18 certificate with no recommended cuts.

With the exception of its early beginning, Trainspotting's marketing strategy bears a strong similarity to Shallow Grave's. The first thing that needs to be taken into consideration is the release date. "You tend to choose a date that has no equivalent competition," explains PolyGram's Julia Short, "so although a film like Toy Story might open, it isn't in the same market. And you tend to open it when you think you'll get lead reviews that week." Although February has been on the cards for some time, Friday, February 23 is chosen as ideal, although efforts to get the lead reviews are scuppered slightly when both Casino and Sense And Sensibility are also scheduled for the same day. Short remains optimistic.

If it's going to work anywhere in the world, it's going to work here.

"We still feel we'll get stronger reviews," she says. "The key to Trainspotting is we now have a pedigree. We can say 'From the makers of Shallow Grave', which is a major selling point." At this stage the teaser trailer goes out to cinemas, while a clutch of West End and London venues are booked for the opening date. The film will have a fortnight's platform release in London and Scotland before opening across the rest of the country on March 8.

"We'll know from the London opening how successful it's going to be," assesses Short, "then we'll be able to make more prints and get them out. At the initial stage we're sending out 120 prints, and if it makes tons of money, it will go into more. If you look at Shallow Grave, 20 per cent of the audience came from the West End, and from the West End and London it was 35 per cent of the audience. So it can be a very large proportion of the box office."

Despite Trainspotting's modest budget, the marketing campaign is priced at a whopping £800,000, due to PolyGram's unfailing faith in the picture. "We're confident it'll make money," confirms Short, "so if we spend £800,000 and take what we think we'll take, we'll break even. Also we're the first territory in the world to release it; so we like to look bullish. If it's going to work anywhere in the world, it's going to work here.”

While PolyGram is concentrating on global domination as far as world distribution is concerned, one territory that has escaped their grasp is the US, where the film will be released in July 1996 through Miramax. The trio's pilgrimage to America to show the film to the powers that be there has been a big success. "I think they were really surprised by it," reflects MacDonald. "They bought it before they'd seen it, thinking they couldn't lose and even if they did, it would still be worth it for the relationship they could have with us - and get us to do an Elmore Leonard novel or whatever it is they want us to do there. But when they saw it they realised it could really be something.”

December 1995

Seasonal ennui puts a spanner in the works. "Ideally, you need four or five months to market a film," laments Short, "and effectively you lose December because everybody's going to Christmas parties, so you have a shorter lead time than you would normally. That's why we've been working so far in advance."

January 1995

The book, together with new artwork taken from the poster is re-published, and the soundtrack album hits stores. The main trailer also makes its first cinematic appearance. In the meantime, the marketing campaign is stepped up, the next stage being the introduction of Trainspotting posters at key British Rail sites. "PolyGram owns about eight poster sites at British Rail stations across the country," states Short, "and we have those all year round. So we're putting up Trainspotting posters, which we think is quite appropriate."

One, at Charing Cross underground station in London, turns out to be 100 feet long. With Boyle, MacDonald and Hodge's work on Trainspotting now over, bar the promotional interviews, their attention is turning towards the imminent pre-production period of their third feature, A Life Less Ordinary, which is still undergoing script dilemmas. "It's a romantic comedy with nasty bits," says MacDonald. "Actually, it was a romantic comedy," grins Hodge, "now it's a Chainsaw Massacre movie.”

One project that isn't on their immediate list, however, is Alien 4, despite rumours in the trade press that Boyle and MacDonald had been snapped up to lend their directing/producing prowess to the movie which promises to bring Ripley back from the dead. "We've been in talks about possibly doing it," explains Boyle, "and they sent us the script. We didn't really want to read it, but it's actually rather good. So we've been talking about it. But it's a startling example of the fact that you think these big films are very organised, and they're not - they just muddle along like any other film."

February 1996

Teaser posters appear at London Underground stations, followed a fortnight later by the real thing. Most of PolyGram's budget is going on billboards, forsaking radio and TV advertising. "The strategy in terms of the ad campaign is to introduce the characters," explains Short, "so the first stage is escalator panels, which will focus on each individual, followed by a bus shelter campaign, again in which each poster will be one character. Then the big sheets feature the whole group."

Ironically, the day that the posters make their initial outing is also the day Trainspotting receives its world premiere in Scotland. In aid of drug rehabilitators the Carlton Athletic Group, with whom the cast spent a lot of time "learning what it's like to be a heroin addict", the film will be simultaneously shown in a Glasgow and an Edinburgh cinema, with Boyle, MacDonald and Hodge introducing the Edinburgh opening, and then hurrying over to the Glasgow venue in time for the movie's conclusion and, naturally, the after-show party. (Additional plans are afoot to have screenings in two other venues around Scotland.)

The future

Trainspotting will be backed up by a countrywide tour, similar to the one that promoted Shallow Grave, in which Boyle, MacDonald and Hodge will attend special screenings followed by Q&A sessions. The film will make its international bow at the Cannes Film Festival in May. "Because it's a British film and it's going to Cannes," explains Short, "it can only open in its home territory, beforehand. "But I think, ideally, most of Europe will go on the back of Cannes."

So, now it's all over, bar the reviews, how to sum up the Trainspotting experience? "What I would say," concludes Boyle, "is that while we've been filming, the book's reputation has been magnified enormously, and I'm glad we took it on while its reputation was growing. I think there's an element to every film you do where you're always glad you got away with it, or at least, you hope you got away with it...”

This article originally appeared in Empire Magazine, issue #81 (March 1996).

Many thanks for their unflagging effort and support in the preparation of this article to Danny Boyle, Andrew MacDonald, John Hodge, Sarah Clark and Jonathan Rutter.