February 8 is John Williams’ eightieth birthday. Williams is indisputably the world’s best-known movie composer, creating cinema’s most memorable themes, imaginative scoring and telling collaborations (his next film with Steven Spielberg, Lincoln, will be their 26th together). The stats speak for themselves: over 140 composing credits, 5 Academy Awards, 3 Emmys. His recent Oscar nods for The Adventures Of Tintin: The Secret Of The Unicorn and War Horse bring his nominations tally up to 47, the most of any living person (and second only to Walt Disney). Yet his significance goes way beyond cold facts and figures: for any movie fan over the past 40 years, he has literally created the soundtracks of our lives and as we have grown up, his music has grown up with us. If he had just given us Star Wars then his place in the pantheon would be assured but factor in Jaws, Superman The Movie, Indiana Jones, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Jurassic Park and Harry Potter and his impact on pop culture is incalculable.

To celebrate his auspicious anniversary, we have gathered together in no particular order 80 of his greatest cues to showcase the dizzying scope and seemingly unfathomable depths of his genius. You would need 800 tracks (and counting) to do full justice to his talent so please leave your glaring omissions, favourite Williams tunes and birthday salutations below.

*First heard in: Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981)*If adventure has a theme it must be Indiana Jones. The story goes that Williams played Steven Spielberg two options for the Indiana Jones theme on the piano and the filmmaker's simple direction was "Why don't you use them both?" The two tunes became the theme and the bridge for the Raiders March, embodying the character's virtues and the film's values to a tee: like Indy, his theme is simple, cocksure determined and direct; like the movie, it combines a pulpy, slightly campy-y parody of '30s adventure music with a warm sincere feel-good dynamic, the tune encapsulating the film's cocksure ability to deliver a good time.

The interesting thing about The Raiders March is that it is a very simple little tune," remembered Williams, "but I spend more time on those bits of musical grammar than anything else. The sequence of notes has to sound just right so that it seems inevitable, like it has always been with us. It was something that I chiselled away at for a few weeks to find the correct musical shape. Those little simplicities are often the hardest things to capture."

Unlike Star Wars, the march doesn't appear over a title sequence at the beginning. Instead Williams dots the theme and the bridge throughout in various guises; the theme is first heard as Indy swings into the Peruvian river and reappears in epic sweep mode during his flight to Nepal and in a triumphant version as Indy climbs onto the sub cheered on by pirates. The bridge, in a comical extended form, underscores his discovery of the snake on a plane — he hates snakes, apparently — and delivers rollicking momentum during the truck chase. Take both tunes as a whole and 31 years later it remains debatably Williams most exciting, exuberant theme, a throwback to movie history that is guaranteed to put a smile on your face in the here and now.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: The Empire Strikes Back (1980)*If the score for Empire has an emotional centre, then this it. Han and Leia's romance may be charged with fizzy repartee but their true feelings are amplified in this sumptuous love theme helping them to share their first kiss. Yet, when things turn dark, the theme is used to do the heavy lifting, becoming grander and gloomier as Han is lowered into carbon freeze and grandiloquent as Luke and Leia watch the Falcon fly off at the finale. Like much of Williams' romantic writing, it is marinated in melancholy as much as melodrama, all mournful horn and sweeping strings. Listen closely to the first two notes of the main melody: they are the same as Princess Leia's New Hope theme.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Hook (1991)*It is only 90 second's long but this prologue for Spielberg's Peter Pan Grows Up comedy adventure is a corker. Premiering on the film's teaser trailer — other trailers for the film featured Williams' music for The Witches Of Eastwick — this appetite whetter is a glorious evocation of swashbuckling and skullduggery, shot through with an elegant simplicity yet soaring on high spirits. If the film that followed matched up to this, it would be a masterpiece.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Superman The Movie (1978)*Stately, noble, tinged with doomed majesty, William's motif for Superman's home planet enters the score with the main theme still ringing in the ears, is just under a minute long but immediately takes up space in the memory. Emerging from a state of uncertainty, it starts on a single trumpet and builds to a shattering crescendo. Unfortunately, because Krypton explodes not long after, we only ever hear fragments of it again.

Listen to an excerpt:

Duel Of The Fates

First heard in: Star Wars Episode I The Phantom Menace (1999)

Rather than leaning heavily on familiar themes, Williams created a whole new series of motifs and cues for the prequels, the most striking and enduring being this rabble rousing choral work that first appeared over the Qui-Gon-Obi-Wan-Darth Maul lightsaber duel. The piece begins with the London Choir singing a powerful chant: Williams adapted an archaic Welsh poem Cad Goddeu in Sanskrit that translates as "Under the tongue root a fight most dread and another raging behind in the head." For Williams, the piece is the "result of my thinking that something ritualistic and/or pagan and antique might be very effective. I just felt the way George staged the duel, on top of that great stairway, the way it's done is so dramatic and so like a great pagan altar, the whole thing seems like a dance or a ballet, a religious ceremony of some kind, probably ending in the death of one of the combatants…"

Yet it's not just the frightening choral work that distinguishes Duel Of The Fates. The repetitive string motif, the main melody that starts on woodwind then transfers up to brass, the thunderous percussion, how it crescendos then stops to regroup — it is a masterwork in organised terror. Williams reprised the theme for Attack Of The Clones as Anakin races to save his mother from Tusken Raiders and it recurs in fragments during the Obi-Wan-Anakin face off in Revenge Of The Sith. It was debatably the best thing to have come out of the prequels full stop.

Listen to an excerpt:

Hedwig's Theme

First heard in: Harry Potter And The Philosopher's Stone (2001)

The greatest piece of music ever written to describe a postal delivery service, Hedwig the Owl's theme was composed before the body of the score, Williams writing it for the trailer and then premiering it in a concert at Tanglewood. "I remember first hearing Hedwig's theme," recalled Potter producer David Heyman. "It was so clear that this was it — majestic and magical." As much as it refers to Harry's feathered friend, the use of the theme, especially in its gossamer light celesta arrangements, suggests a broader motif for the creative and capricious nature of magic in the series — it also serves as a kind of unofficial theme for the entire franchise. Williams composed the first three Potter pics but the original remains the best, a memorable mix of whimsy, mischief, adventure and menace topped with a touch of pomp and circumstance that is one of the composer's best from the noughties.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Jaws (1975)*It's a classic movie moment. Three men work together to build something to kill a beast. In this case, Quint (Robert Shaw), Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) and Brody (Roy Scheider) construct the anti-shark cage (or "Ant-eye shark cage" as Robert Shaw pronounces it) for Hooper to descend into the depths of the ocean. It's a dramatic scene and Williams reprises a secondary theme he has been using throughout the strive aquatic but in its most rigorous dramatic statement yet, layering instruments over a building violin structure that culminates in a shattering climax. Unlike Hooper, Williams' tune has got lots of spit.

Listen to an excerpt:

Yoda's Theme

First heard in: The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

Full of delicate orchestration and sensitive playing, Yoda's theme represents one of the few optimistic passages in a mostly downbeat sequel score, particularly in its playful pizzicato rendition as the Jedi master puts Luke through his paces. The theme gets a whimsical reprise in E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial when the alien passes a kid in Yoda fancy dress at Halloween — when Spielberg showed the film to George Lucas, he didn't pre-warn him about the homage and elicited a delighted reaction from the Star Wars creator.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: The Witches Of Eastwick (1987)*Williams' music for George Miller's devilish comedy contains one of his most insidious ear worms. To represent the machinations of the three housewives (Michelle Pfeiffer, Susan Sarandon, Cher) who conjure up the Devil himself (Jack) the composer creates a whirling dervish of tune, a wicked waltz utilising violins, woodwinds and harpsichord. It works in a light-hearted spritely iteration but can also be amped up for flash and thunder dramatics when needs be. Like much of Williams work, you can listen to it just once and it stays in your head for days.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1984)*It is the musical highlight of the Temple Of Doom score. A brutal relentless march symbolizing Indy's rescue of the slave children that starts on a military snare drum augmented with metallic chain percussion and takes off into something victorious. It holds a melodramatic version as Short Round becomes a slave and carries an Eastern arrangement that hints at the film's locale but at it's most rousing, it is the musical embodiment of fortune and glory.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Star Wars Episode IV A New Hope (1977)*Early on during the Star Wars recording sessions at Anvil Studios in Denham, George Lucas took a break during proceedings to phone a friend. The friend he called was Steven Spielberg, who had recommended the composer to Lucas following Jaws. As the London Symphony Orchestra played the now familiar themes for the first time, an excited Lucas held the phone out towards them for half an hour to share in the excitement.

What Spielberg was listening represented a seismic change in movie music — in soundtrack terms there is Before Star Wars and After Star Wars. Eschewing Lucas' idea to score the movie 2001-style with existing classical music — as temp tracks, Lucas employed Stravinsky, Miklos Rozsa's Ivanhoe (for the main title), Bruckner's Ninth Symphony as Luke's theme and Dvořák's New World symphony for the medal ceremony— Williams created sweeping themes in a then defunct Hollywood tradition, grounding the otherworldly characters and settings in a familiar musical landscape.

The subsequent 90 odd minutes of music not only brought Williams his third Oscar and the biggest selling non pop soundtrack of all time, it ushered in a renaissance in large scale orchestras in general and a Wagnerian leitmotif approach in particular that sees a phrase or melody signify a character, place or idea ("dramaturgical glue" as Williams calls it). As such what we now know as the Star Wars theme initially started life as a motif for Luke Skywalker — we hear a particularly warm rendition the first time we meet him down on the farm, a triumphant version when he pulls the grapple hook from his belt to swing across the Death Star and an urgent anxious version as he zeroes in on the Death Star exhaust port. Six films later, the fanfare is more widely perceived as a statement representing the whole saga, kick-starting each film with an intense burst of orchestral energy. The theme became so popular that Meco's disco version hit number one on the Billboard chart and has been covered in styles as diverse as reggae (Ska Wars), baroque, skiffle (courtesy of Mark Kermode) Japanese Shamizen and by lounge lizard Nick Witter{

Listen to an excerpt:

First heard in: Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981)"A cross between Dark Victory and the love scene from Casablanca" is Spielberg's description of the music to represent Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen). It remains one of the loveliest of Williams' gentler themes — receiving its best rendition during the movie as Marion tries to find a place to kiss a battered and bruised Indy — but gets a sweeping rendition as the action moves to Cairo and a melodramatic airing as Indy watches Marion get blown up (don't worry, she's alright). It is perhaps too delicate than the character herself would like but it is a tender moment of beauty in a score dominated by boys-y bravado.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Jaws (1975)*It is a major part of any film composer's job description to provide music for a montage sequence. In Jaws' case, this means a sequence juxtaposing a ferry-load of Fourth of July holidaymakers arriving in Amity with Brody and Hooper's frantic attempts to make the beaches safe. In contrast, Williams gives us a refined but light-hearted classical piece of Americana (it sounds more New England than Wild West), starting with a stately string melody before giving away to bright brass and woodwind flourishes. On the original soundtrack, the cue was named Promenade and given an uncharacteristically black humoured subtitle — Tourists On The Menu.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977)*It remains one of the most effective openings in movie history. Simple white titles appear over a black background. Slowly, we hear an ethereal, shimmering noise that changes pitch as it increases in volume, reaching a crescendo as seemingly the whole ensemble delivers one great big orchestral hit as the screen goes to black to a few frames of white to the middle of sandstorm. It might feel like an obvious shock tactic but as a way of getting the audience's undivided attention from the get-go, it works a treat.

Listen to an excerpt:

Theme

First heard in: The Sugarland Express (1974)

While the likes of Duel had been done by Universal contract composer Billy Goldenberg, Spielberg turned to his vast soundtrack album collection to find a composer for his debut feature film. He felt The Sugarland Express needed big broad symphonic music so was immediately drawn to Williams' work and invited the composer to see the picture.

As was soon to become the norm for their working partnership, Williams persuaded the director that a different musical direction was needed. Rather than something big and bold, Williams felt the small scale story of a young Texan couple (Goldie Hawn, William Atherton) going on the run from a cavalcade of cops to pick up their young son from adoptive parents needed something more intimate and human. To help locate the film in its Southern state, Williams used the harmonica as the primary voice in the composition and enlisted the celebrated Belgian harmonica maestro 'Toots' Thielemans' to be his musical conduit. The theme in the movie is simple, folksy and direct, less ornate than the concert arrangement below, and might not stand at the forefront of the Williams-Spielberg collaborations. But Sugarland remains important in the composer's pantheon for the start of a beautiful, enduring and still creatively exciting partnership.

Listen to an excerpt:

Theme From Superman (Main Title)

First heard in: Superman The Movie (1978)

Jerry Goldsmith, who had scored Richard Donner's previous film The Omen, was due to score this big-budget take on the Man Of Steel — Goldsmith's score for Capricorn One even played over Superman teaser trailers. When scheduling conflicts forced Goldsmith to leave the project, Williams stepped in and delivered some of his best work in record-breaking time. Like many Williams main themes, Superman's signature tune is built around two killer elements — a brass fanfare that suggest the character's Olympian qualities and a more spirited theme that embodies his comic book heroism without ever descending into pulp. It is the benchmark that any superhero theme must reach — Bryan Singer understood this and just borrowed it wholesale for Superman Returns — and if the USA had any sense, they would make it their national anthem.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: JFK (1991)*Williams has composed music for US Presidents in both movies —John Adams in Amistad, Nixon for er Nixon — and actuality — Williams composed Air And Simple Gifts for President Obama's inauguration — but his music for his second collaboration with Oliver Stone remains the best. Williams' theme pays tribute to the nobility and optimism Kennedy represented yet the mournful trumpet solo — stand up soloist Tim Morrison — expresses the regret and tragedy at his passing. Williams is currently in Chicago researching his next presidential anthem for Steven Spielberg's Lincoln.

Listen to an excerpt:

First heard in: Far And Away (1992)"You're a corker, Shannon. What a corker you are," says Tom Cruise's Joseph Donnelly to Nicole Kidman's flame-haired Shannon Christie in Ron Howard's oirish immigrants in America picture yet this isn't the tip of the film's Gaelic gall. As is Hollywood law regarding any American movie with Irish subject matter, Williams used the Chieftans AND Enya to evoke Donnelly's homeland — there are lots of pipes, penny whistles, fiddles and bodhrans —in some lovely lyrical passages but the strongest material comes in his use of music associated with Westerns to create the energy of the Oklahoma Land Rush and the optimism of a new frontier.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: The Towering Inferno (1976)*Before he was the king of the blockbusters, Williams was the master of disaster. The composer had collaborated with producer Irwin Allen during his TV days — his Lost In Space Theme is a mini masterpiece — and had turned in the score for The Poseidon Adventure and the non-Allen produced Earthquake. Still, this remains his best work in the disaster arena, the highlight being the opening overture that covers the first five minutes of the film, a helicopter journey revealing the majestic but doomed building. From this perspective, it feels a bit '70s but it is a rousing, urgent expansive adventure theme that has more wattage than the all-star cast put together.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Amazing Stories (1985)*It was such a great idea on paper. Weaned on shows such as Twilight Zone and Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Steven Spielberg conceived Amazing Stories as a place to bring to life his stories, plots and high concepts that never found a home in cinemas, delivered by big name directors with the panache and the production values of a big screen outing. This sense of scale dictated a title sequence that details the entire history of storytelling from campfire tales, via ancient civilisation, books, CG knights, ghosts, spaceship to a family sitting around a TV watching the campfire storyteller spinning his yarn. To accompany the intro, Williams delivers one of his most sprightly adventure tunes — from this perspective it is also works as a time machine taking you right back to the mid '80s. Unsurprisingly, Williams also composed the score for Spielberg's two entries — Ghost Train and The Mission — and while the series was wildly uneven, Williams' theme toon still shines.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Jaws (1975)*Along with Happy Birthday To You, Williams' theme for Spielberg's man-fights-fish blockbuster may be the most recognisable piece of music in the world. Yet the simple two-note alternating pattern didn't convince the director at first — his initial reaction on hearing the theme on the piano was to laugh. "At first I thought it was a little too primitive," remembered Spielberg. "I wanted something a little more melodic for the shark and then Johnny said "What you don't have here is The L Shaped Room….you have made yourself a popcorn movie." And he was absolutely right." For Williams, the mindless primal progression of the theme mirrored "the effect of grinding away at you, just as a shark would do instinctual, relentless, unstoppable." Film score theorists have suggested that the motif represents the heart rate of the shark itself, starting slow then building to a frenzy when it attacks, as if we are tuning in to the shark's psyche. As such, we only hear the theme when the shark is present; during the red herring scenes — such as The Fake Fin Incident — the absence of the theme is signalling this is a hoax.

Given the effectiveness of the two note — actually E and F — signal, it is often easy to miss the real hero of the Jaws theme: a resonant horn motif played by tuba player Tommy Johnson. Given the melody is in such a high musical register it would seem that the theme would be better suited to the French horn rather than the low-end tuba. But Williams felt the instrument gave the theme more weight, more threat. For the movie, the music does much to make us forgive the fake shark, Spielberg suggesting it accounted for around a third of the film's $470 million box office. In the wider world, it has entered the culture as a signifier of any kind of encroaching threat, turning up in the likes of Airplane!, Caddyshack, The Secret Of My Success, Top Secret and Swingers.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Black Sunday (1977)*John Frankheimer's thriller centres on a Palestinian terrorist plot to detonate a bomb in the midst of the Superbowl with the US president in attendance. To detail the bomber's rigorous preparations, Williams unleashes a steely, black-hearted fugue fused with an inexorable rhythmic progression. The theme shares musical DNA with other powerful multi-stringed Williams pieces — The Shark Cage Fugue from Jaws, In The Belly Of The Steel Beast from Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade — and has a seriousness and classical rigour that belies Williams' reputation as a purveyor of easily hummable themes. The score also served to mark the end of the Master Of Disaster phase of Williams career: next came Star Wars.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Presumed Innocent (1990)*It could be a pub quiz question: apart from Star Wars and Indiana Jones, what Harrison Ford movies has John Williams scored (alright, you might have to be drinking in a particularly nerdy pub)? Answer: 2. One is Sabrina and the other is this erotic thriller — Ford is the unlikely named Rusty Sabitch, a lawyer who finds himself in the frame for murdering his own mistress — that sees Williams balance themes of family, passion and murder, under-laying a lush romantic piano theme with sinister orchestral churning, unsettling timpani and the odd chilling synth effect. A definite change of pace from Williams' blockbuster mode, it became a staple of thriller trailers in the '90s such as The Juror.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Family Plot (1976)*It could not be more apt that Williams composed the music for Alfred Hitchcock's last movie. Often considered the natural successor to Hitchcock's composer Bernard Herrmann as the movie music master, Williams was the perfect choice to score a lighter Hitchcock flick, a dark comedy involving faux psychics, kidnappings and diamonds. Overflowing with musical wit, Williams score is full of satire — a parodic ethereal choir evokes sham séances, harpsichord to suggest deviousness — but also has lovely free-from melodies to boot. Later in his career, Williams would play homage to Herrmann in specific instances (as Han Solo opens the cargo hold of the Millennium Falcon, Williams works in a three note refrain from Psycho; in The Terminal, Williams gives us a quick blast of the Cape Fear theme) and as a general influence (the harried rhythms of Minority Report). Yet he made his own distinct mark in the Hitchcockverse with Family Plot.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: The Fury (1978)*Fitting this in between Close Encounters and Superman The Movie, Williams' music for Brian De Palma's overblown kids-with-telekinetic-powers thrillers — it's the one where Amy Irving blows up John Cassavetes with her mind — ranks among his strongest suspense scores. It contains sustained stretches of full-on horror music employing synthesisers and Theremin for added weirdness, but at its best, delivers a theme that has the feel of an otherworldly waltz, never easy to get a handle on, bewitching in its gentle iterations, thunderous in its bolder versions. De Palma has yet to work with Williams again which is a shame: his grandiose sense of the visual pulled out compelling work from the composer.

Listen to an excerpt:

The Magic Of Halloween

First heard in: E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

Over his career, Williams has written much music to convey a sense of flight, be it through a WWII prisoner camp, around the skyscrapers of Metropolis or over the Quidditch pitches of Hogwarts. Yet Williams greatest hymn to soaring through the skies comes in E.T. The Extra Terrestrial. The theme that accompanies cinema's most famous ride across the moon sees Elliott and E.T. almost carried through the night by the string section, the theme getting a triumphant statement as they get silhouetted by la luna. Yet the sense of euphoria we feel is part musical alchemy but also part clever foreshadowing. Williams has been preparing us for the theme throughout the film, suggesting the theme first in part, then in whole in various guises — we hear it as E.T. levitates the balls to display the solar system — so by the time we get to the forest fight, it feels like we've always known it. In this sense, the theme stands not just for flight — at the climax of the film it wafts the boys over the cops with guns/radios (delete where applicable) — but also for the creature's ability to wield magic and by extension the magic of the film itself.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Harry Potter And The Philosopher's Stone (2001)*Kicking off with a robust version of the second half of Hedwig's theme (although it is perhaps better characterized as a general signifier of Hogwarts, often appearing over long shots of the school) this segues into a warm theme that suggests Harry and the relationships in his life, be they familial or friendship. Light, spirited and infectiously optimistic.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Hook (1991) *It's a little known fact that Steven Spielberg's Hook started life as a musical. Williams had collaborated with Bond composer Leslie Bricusse (also see The Love Theme From Superman — No. 38) on a Peter Pan stage production, completing ten songs before the project stalled. Three of the songs found their way into Spielberg's finished film — We Don't Wanna Grow Up is performed by kids in a school play at the start of the film, Pick 'Em Up is the song that sees the Lost Boys whip Peter into shape, When You're Alone is the ballad that Maggie sings to comfort herself in Hook's clutches — but, perhaps because Williams was working of the project for such a long time, it means that Hook is one of the composer's richest, varied, most satisfying outings. Few of Williams' (or anybody else's) scores have Hook's multitude of memorable themes, covering comedy tropes (for Hook and Smee), melancholy (Peter recalling Pan's past), delicacy (Granny Wendy), march-like formality (the food fight) and high adventure as Peter Banning (Robin Williams) takes flight as Peter Pan.

Listen to an excerpt:

The Asteroid Field

First heard in: The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

While Williams' music is unfairly characterised as simplistic, here is the perfect riposte. With a failed hyperdrive, the Millennium Falcon heads into an asteroid belt to evade the Imperial fleet, dipping in and out of floating boulders, and the orchestra follows Solo every step away, swooping and soaring around the musical register. There are frantic rhythms, and heroic brass fanfares all adding up to a complex workout for the London Symphony Orchestra.

Listen to an excerpt:

_First heard in: NBC Nightly News_In 1985, NBC commissioned Williams to write a quartet of pieces for its television news output. The standout is The Mission, a strident piece for the network's Nightly News show. Analysing the difference between American and British news themes, Bill Bailey described this theme as "E.T. on a horse being chased by Darth Vader." As good as that sounds, this is better — and here is Bailey providing his own lyrics.

Listen to an excerpt:

Jurassic Park A Theme

First heard in: Jurassic Park (1993)

Given it is about unstoppable forces of nature (be it genetically modified), you might have forgiven Williams for going down the Jaws route for his musical representation of some older fearsome critters. Yet Jurassic Park's theme couldn't be more different. As the Palaeontologists, chaos theoretician and lawyer come across a brachiosaurus grazing by a tree, Williams gives us a string and choral piece — the voices are subtly effective — that speaks to the majesty of the animals and the wonder of the awe-struck scientists (it doesn't speak to the lawyer at all). It is romantic and ennobling and a good shout for the most gorgeous thing that Williams has ever written.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Harry Potter And The Chamber Of Secrets (2003)*Following on from his music for Harry's pet, the second Potter flick saw Williams create a memorable theme for Dumbledore's bird, Fawkes the Phoenix. It's a lovely lilting ditty that as the drama intensifies, Williams twists into something edgier during the duel with the basilisk, punctuating the battle with brass flourishes and explosive percussion. But it is best, as here, in this simple elegant arrangement.

Listen to an excerpt:

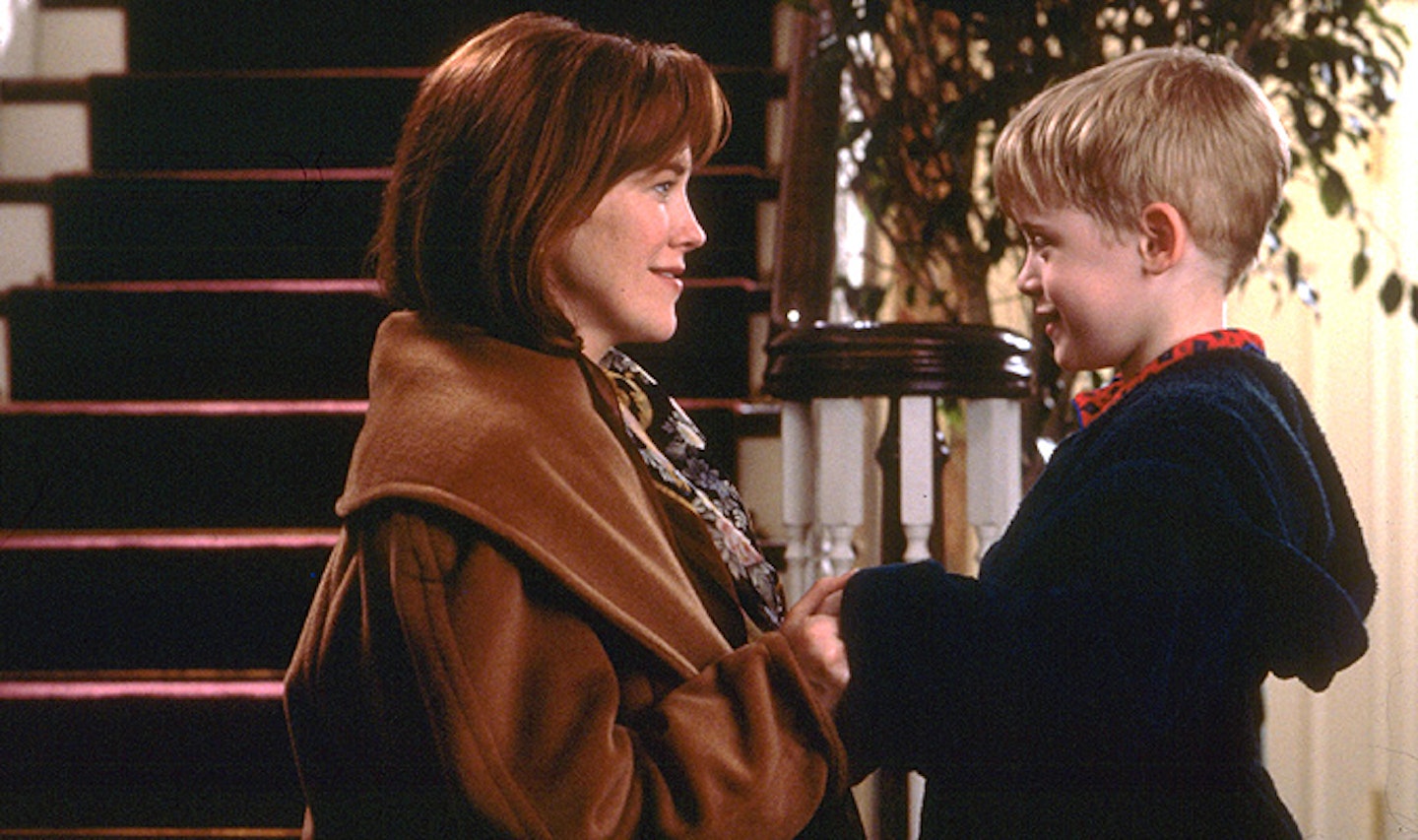

*First heard in: Home Alone (1990)*If you were looking to buy a John Williams Christmas album — the kind that Michael Bublé does — then Home Alone fits the bill. The first time the composer worked with filmmaker Chris Columbus — they have worked together five times in all — Williams' score throws every kind of tinkly, sleigh bell-y sound in the songbook mixing it with up with kind of comedy music that Scott Bradley composed for Tom & Jerry to describe Kevin McAlister (Macaulay Culkin)'s run-ins with the two hapless criminals (Joe Pesci, Daniel Stern). You may require insulin to listen to this and it only really makes sense in the run-up to Christmas but it is a collection of pretty tunes that also highlights another bi-product of Williams' success. Over the years, he has done arguably more than anyone to introduce kids to classical music, be it Star Wars in the '70s, Indy and E.T. in the '80s and Harry Potter in the noughties — Home Alone and Jurassic Park represent this influence in the '90s, hugely popular family films that did wonders for exposing children to quality music rather than Mr. Blobby novelty records.

At the heart of the film is the song Somewhere In My Memory and Williams reworks the tune into the spine of the score. Despite being the most Oscar nominated person alive, Williams has had a chequered history with the Best Song category—chequered in that he has never actually won it. In the '70s, his nominated song Nice To Be Around from Cinderella Liberty lost to The Way We Were. In the '80s, If We Were In Love from Yes, Giorgio was pipped to the post by Up Where We Belong In the '90s, When You're Alone from Hook and Moonlight from Sabrina were beaten to the punch by Beauty And The Beast and Colors Of The Wind (Pocahontas) respectively. Somewhere In My Memory lost out to Dick Tracy's Sooner Or Later (I Always Get My Man) but Williams may have had the last laugh: Somewhere In My Memory has become a holiday staple in the US, often performed by choirs and schools. Not even Madonna is singing Sooner Ot Later (I Always Get My Man) any more.

Listen to an excerpt:

First heard in: Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (1989)"The search for the grail," says Marcus Brody to Indiana Jones at one point during the Last Crusade, "is the search for the divine in all of us." To wit, Williams digs out a graceful theme, very English and pastoral in nature, that suggests both the mystique of the artifact and the dignity of the keeper himself. As Indy knows — but the baddies don't — the Grail is a thing of noble simplicity bereft of any flashy adornments. Williams' stately motif is a perfect replica.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Star Wars Episode IV A New Hope (1977)*No composer can do granite-hard battle music better than Williams and this is one of the finest examples. As Han and Luke wait it out for a TIE Fighter onslaught, the orchestra plays with anxious, expectant rhythms. The wait comes to an end with a broadside of chopping strings and bold-as-brass brass that delivers a full blown adrenaline rush but a surprisingly catchy one too — you just can't help but sing along{

Listen to an excerpt:

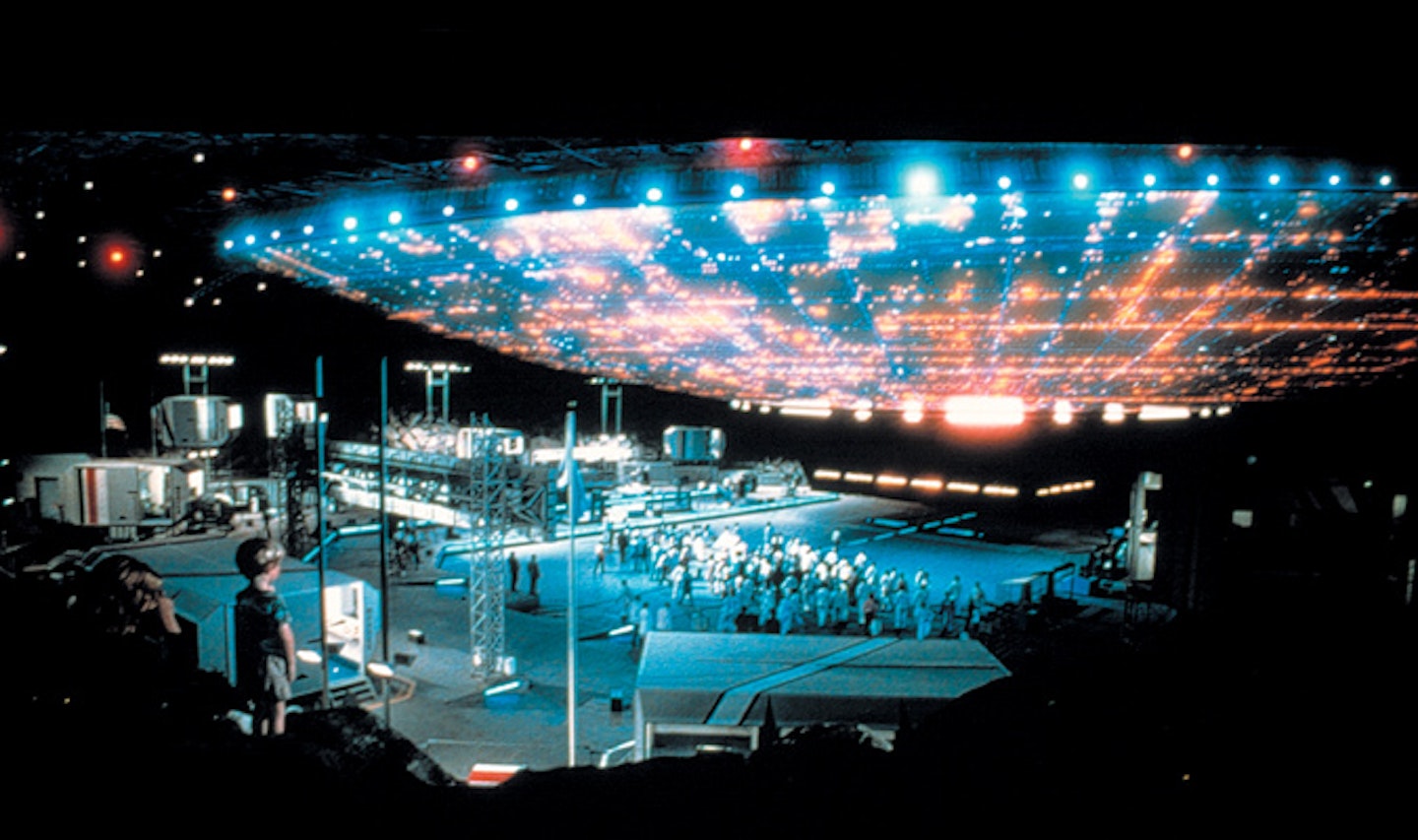

*First heard in: Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977)*Not content with having the most famous two-note motif in movie history — the E and the F of Jaws — Close Encounters also gave Williams the most famous five note sequence as well. Few films have music more integrated into the fabric of their plot than Spielberg's UFO epic, the screenplay built on the notion that mankind and aliens communicate through lights, colour but mainly music.

"I don't know where that idea came from," Spielberg told DVD documentarian Laurent Bouzereau. "I just thought it would be really cool to have aliens and humans communicating by what reaches us quicker than anything else which is the passion of music and my own love of music was sort of a part of that too."

It was Williams key musical task to give form to Spielberg's inter-galactic greeting. The composer's initial idea to was to have seven or eight notes, perhaps echoing When You Wish Upon A Star, the song from Pinocchio that Spielberg used to sum up the film's optimism. Yet the director was adamant that the signal should only be five notes, "more like a ding dong, it's not a melody, not even a phrase," according to Williams — this was to prove a challenge for the composer.

"It was very difficult to make the signal have any kind of musical sense," recalled Williams. "I remember writing maybe 250, 300 of these things. I had a few meetings with Steven to play him all of these little themes and we could never figure it out. We were never able to say 'Eureka! This is exactly the one we want!" I thought we'd examined everything; maybe three hundred examples of the five note variations within the scale and Steven said, "Oh there must be more. We'll call this friend of mine who is a mathematician to ask him how many five-note combinations within the twelve-note scale there are. Steven's friend rang us back an hour or so later and he said, 'Approximately 134,000'."

In frustration, the pair landed on one of the initial 300 variations. This was all done before Williams had seen a frame of film or even read a script and the notes — B flat, C, A flat, (octave lower) A flat, E flat as heard at Devil's Tower — were recorded a year before filming commenced. Even though, it is barely a melody, the theme works well in its full-blown orchestral version that plays over the end of the movies as it does in this stripped down synthesizer-mothership conversation. In the 35 years since the movie came out, it has became a by-theme for any kind of alien activity and has been referenced in culture as diverse as Moonraker — it is the sound of a door code at Drax' s Laboratory — Monsters Vs. Aliens and ITV's happily defunct Heartbeat.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)*As all the plot strands of E.T. converge towards the end— E.T.'s need to get home, the government's desire to nab him, Elliott is caught in the middle — Williams draws on all his thematic material and intelligently weaves it to tell the story musically. The score flits between the menacing brass motif that has stood in for Keys and co. and a theme we have previously heard more playfully — as Elliott lays out Reese's Pieces for E.T. — now been ramped up into a full urgent, belting orchestration. The piece also showcases Williams at hitting visual sync points with his music — listen out for the musical sting that accompanies the cut to the Govt. henchman. The urgent theme also gets a lovely piano reprise as the end credits roll.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Superman The Movie (1978)*The theme representing the romance between Superman and Lois Lane was originally planned as a full-blown song, Can You Read My Mind, for Margot Kidder to sing. It even got to the stage where lyrics were penned by Bond lyricist Leslie Bricusse until Donner nixed the idea, turning it into a voiceover during the in-flight courtship scene. This was A Good Thing because a) Bricusse's lyrics were awful ("You can fly/You belong in the sky") and b) it remains one of Williams most gorgeous love themes, by turns bittersweet and high flying, starting with a gently rocking figure and closing in contemplative mood.

Listen to an excerpt:

Final Duel

First heard in: Star Wars Episode VI Return Of The Jedi (1983)

Williams had only flirted with choral passages in the first two Star Wars flicks — the heavenly voices that greet the Falcon's arrival at Bespin — but went the full hog for the operatic ending of Jedi. Williams not only creates a new diabolical all male choir motif for The Emperor, but for the moment where Luke comes out of hiding to duel with Vader ("If you will not turn to the dark side, then perhaps she will." "Noooooo!"), Williams unleashes a devastating choral statement that gives the duel even further mythic resonances. Slower and richer than Duel Of The Fates, it was proof that vocal arrangements could work in the Star Wars musical universe, something Williams explored to great effect in the prequels.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Jurassic Park (1993)*To counterpoint the grace and beauty of his A motif, Williams created a rousing adventure theme for the theme park. Heard in its most dramatic statement as the InGen helicopter arrives at Isla Nublar, it is a classic adventure tune, a brass fanfare augmented by timpani and crashing cymbals. Less pulp-y than Raiders, less formal than Star Wars, it is the only music suitable for being chased across a pasture by 65 million year old outsized chickens. It is astonishing to think that Williams composed the diametrically opposed music for Schindler's List straight after.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Schindler's List (1993)*When Steven Spielberg presented John Williams with the idea of composing music for his monumental Holocaust drama, Williams suggested, "You need a better composer than I am for this." "I know," Spielberg replied, "but they are all dead." What Williams eventually delivered is debatably his greatest achievement, an emotionally devastating work that transposed the horrors of the holocaust with serene grace and delicate beauty. The film's approach is best summed up in the main theme, a simple heart-melting work that is affecting on both solo violin and piano and conveys the sense of humanity and dignity that so many tried to hold onto during the Final Solution, not to mention the tragedy of those who lost their lives. Interestingly, it also owes something to German musical traditions, perhaps suggesting Schindler himself. Academy Award number five was never in question.

"Most of our films together have required an almost operatic accompaniment, which is fitting for Indiana Jones, Close Encounters, or Jaws, recalled Spielberg. "Each of us had to depart from our characteristic styles and begin again. This is music to be attended with closed eyes and unsequestered hearts."

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981)*There are various themes representing ancient artefacts and mystical powers during Raiders — listen out for the string motif that sees Indy approach and switch the temple headpiece— but his music for the Ark of the Covenant remains the highlight. Obviously it appears as the power of the Ark is unleashed but the theme gets its first major workout as Indy discovers the resting place of the Ark in the map room, choirs adding to the gravity, power and mystery of the motif until pretty much the entire orchestra comes in as the resting place is revealed. Such orchestral colour obviously earned Williams another Academy Award nomination — number 16 — but he lost out to Vangelis' Chariots Of Fire. The Academy were clearly digging in the wrong place.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Superman The Movie (1978)*The musical march is a much-utilised weapon in the Williams arsenal and this is one of his most famous. It not only catches the tongue in cheek quality of Gene Hackman's Lex Luthor, the woodwind instruments and tuba playing the tune for its comedic stylings, but as the music gets bigger and brassier, building in more and more orchestration, it seems to skewer Luther's pomposity and delusions of grandeur as well. Tons of fun.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Star Wars Episode II Attack Of The Clones (2002)*The Episode II theme is a hymn to doomed love. Like many Williams romantic theme, Across The Stars starts gentle — the theme starts on oboe with violins and harp providing a mixture of dark (violins) and airiness (harp) — before building to a large-scale string and horn arrangement full of epic sweep and huge passions. As befits the film's downbeat mood, the orchestral manoeuvres turn dark in the second half, with low-end strings and tubas expressing disquiet. As you'd expect, it flirts with ideas from The Imperial March and soundtrack boffins have suggested it is an inverted version of Luke's theme, hinting at the connection between mother, father and son. As ever with Williams, the theme is put through the manipulator, turning up as a light, flighty young love theme in the first half and something much more operatic as Anakin (Hayden Christensen) and Padmé (Natalie Portman) enter the arena to face certain death. Soaring one minute, breaking your heart the next, it's an example where Williams creates music far richer than the characters deserve.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Jaws (1975)*At a certain point around the hour mark, Jaws shifts gears from a suspense thriller cum Watergate paranoia flick to a high adventure movie. As Quint, Hooper and Brody first encounter the shark and try to stop it submerging by harpooning it with bright yellow barrels, Williams turns Jaws into a pirate movie, dissipating the mood of dread and fear with spirited strings and blazing brass that recalls the golden era of adventure scores by Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Max Steiner — Spielberg even nicknamed Williams 'Max' in honour. This is so stirring you can almost feel the sea spray on your face.

Listen to an excerpt:

Incident At Isla Nublar

First heard in: Jurassic Park (1993)

This is the kind of suspense cum action cue that Williams excels. A shifting snaking sinuous string motif that ebbs and flow, it is used to represent desperation stations in the park, be it dino-related — this version covers raptor action — or human-centric — a more elaborate take sees it cross cut between Alan Grant and the kids climbing the electric fence while Ellie Sattler labours to turn the electricity on. It's great to the ear but an assault on the nervous system.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977)*For many Williams greatest skill is his knack for coming up with accessible tunes that audiences can whistle leaving the cinema. Yet he is equally adept at creating the polar opposite, troubling atonal colours that are usually the province of avant-garde classical concert halls. It's a technique Williams frequently uses in the Indiana Jones movies to suggest scary animals — listen to the strings in the Well Of Souls — but it gets perhaps its most extreme example in Close Encounters. As aliens descend to abduct little Barry Guiler (Cary Guffey), the house goes ape-shit, the record player turning on (playing Chances Are by Johnny Mathis), the hoover coming alive and the floor vent screws slowly unscrewing themselves. Williams enhances the terror with full-on orchestral and choral tumult, the ensemble churning, rumbling, ascending and stinging for all they're worth. This is what it must sound like inside David Lynch's head.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981)*Back to Indy. In the liner notes for the Raiders soundtrack, Steven Spielberg suggests that all Indiana Jones had to do survive the perils of his adventure was to listen to John Williams score — "it's sharp rhythms told him when to run, it's slicing strings told him when to duck." It's a meta idea and nowhere is it clearer than during Egyptian bazaar dust up: as Indy sees off Arab ambushers, a lively light-hearted motif accents the choreography of the fight, upping the fun factor without ever diluting the excitement. It is the first sketch for a kind of playful action cue that would recur in the likes of Harry Potter.

Listen to an excerpt:

First heard in: Stepmom (1998)

Producing one of his most restrained scores — also see Stanley And Iris, The Accidental Tourist and Always — Williams replaced original composer Patrick Doyle (both later worked on Harry Potter) to soundtrack Chris Columbus' sudsy drama about the rival between Ed Harris' new girlfriend Julia Roberts and his dying ex-wife Susan Sarandon. The dominant mood is an airy orchestral score augmented by Christopher Parkening's classical guitar, but the standout is a catchy little scherzo that has hints of a hoedown. It's proof that even when the film isn't fantastic, you can rely on Williams to deliver the goods.

Listen to an excerpt:

The Catamaran Race

First heard in: Jaws 2 (1978)

There are soundtrack experts who argue that Williams score for the Jeannot Szwarc's fin de sequel is a more enjoyable listening experience than his Oscar winning music for the first one. Perhaps because the film is populated with teens, Williams gives the above-the-water music lots of pep, his music for the Catamaran race fizzes along on joyous brass, seemingly skimming through the water at a rapid rate of knots. And the next time it is on late on ITV 1, try and stay awake for the end credits music — it's really lovely.

Listen to an excerpt:

The Imperial March (Darth Vader's Theme)

First heard in: The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

The Imperial March is so ingrained in pop culture in general and film music in particular that it is easy to forget that Darth Vader's barnstorming theme didn't arrive until the second (fifth) Star Wars movie. Williams composed a stomping imperial theme for A New Hope — it accompanies the Falcon entering the Death Star— yet it became the only major motif that didn't recur for the sequel. Instead, given the Empire's return with a vengeance, Williams composed a brand new bellicose piece of controlled aggression driven by brass, percussion and an unrelenting triplet figure that doesn't let up, even in the quiet middle bit. It stands not only for evil incarnate, it has a grandiose, self important bombast that makes it a favourite in sports stadia, political addresses and Navy recruiting ads. It has been covered by heavy metal legends, dogs. For the prequels Williams cleverly performed a remix of his own, inserting the March's musical ideas into both Anakin's Theme (check out the last four notes) and Episode II's Love Theme, subtly reminding us of the boy's destiny.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Hook (1991)*If you listen to Hook, there are certain passages, full of high drama and touching poignancy that sound anything but a family adventure movie. Happily, there are also moments of pure pantomime. When sidekick Smee parades the captain's Hook on a cushion through pirate town towards its owner, Williams delivers colourful cartoonish accompaniment almost leading the bumbling pirate on a merry dance.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: The Los Angeles Olympics (1984)*Williams has scored much music for fictional sporting events — a whimsical tennis match in The Witches Of Eastwick, the pomp of Podracing in The Phantom Menace and Quidditch in Harry Potter, an impromptu football match in Stepmom — but he also composed the world's biggest sporting spectacle, the Olympic Games, this time in Los Angeles in 1984. Before starting Williams had restrictions imposed on him; it had to include an opening fanfare to be played by herald trumpets and it needed to cut into bite-sized pieces that could work as stings to bookend ad breaks. Williams solution is the great Olympic theme, starting with a trumpeted fanfare, then segueing into a broad noble theme that for Williams represents "the spirit of cooperation, of heroic achievement, all the striving and preparation that go before the events and all the applause that comes after them." The BBC agrees: it invariably wheels the theme out as they round up the nominees for Sports Personality Of The Year.

Listen to an excerpt:

Sayuri's Theme

First heard in: Memoirs Of A Geisha (2006)

Steven Spielberg had circled Arthur Golden's novel about a young girl sold into the life of a geisha for years so John Williams' attachment to the project — even when Rob Marshall stepped in as director — was no surprise. Employing an intelligent and tactful use of Japanese instrumentation within the context of a Western orchestra, Williams' score is gentle and intimate. Williams brought in two virtuoso performers he'd worked with before: violinst Itzhak Perlman who played on Schindler's List and cellist Yo Yo Ma who appeared on Williams' underrated score for Seven Years In Tibet, It is Ma who shines on the film's central piece, Sayuri's Theme, a slow, solemn, simple haunting theme reflecting the grace and sadness inherent in the character's life.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (1989)*Even more so than Temple of Doom, Williams kept the Indiana Jones march under the character's battered fedora for the third installment, creating a wide range of themes for the 110 minutes that still feel part of the Indyverse. This chase music is perhaps the best of the bunch, perfectly capturing the series' sense of danger and comedy in the same piece and also skillfully weaving in character motifs — the derring do of Indy, the fussiness of Henry and the evil of the Nazis — into a thrilling ride. Spielberg calls it 'a wild fox hunt'. He's not wrong.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Jaws (1975)*As an entire score, Jaws is so much more than its trademark two-note theme, full of different textures and moods. To score the Orca pulling out of the Amity harbour to begin its sea quest (no DSV), Williams signals the start of adventure with a horn motif, then segues into part sea shanty/part Irish jig that is as playful as anything that Williams has ever created. When you compare this to some of the film's darker tones, it is this kind of range that won Williams his second Oscar.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Jurassic Park The Lost World (1997)*Eschewing the awe and wonder theme of the first movie, Williams signature tune for the JP sequel takes on the feel of an epic trek into a particularly dark jungle. It has a deliberate majesty in its Main Theme arrangement but Williams delivers an amped up version to cover Roland Tembo (Pete Postlethwaite) and his hi-tech hunting team on a dino safari, the driving drums, slapping percussion and manic strings adding real spirit and energy to the chase. A brutal, brilliant battering of the eardrums.

Listen to an excerpt:

The Tale Of Viktor Navorski

First heard in: The Terminal (2004)

Composing music for comedy is a tricky business. It can either be so brazenly dramatic that it plays as parody or it can be so light and jaunty it can quickly get irritating. Williams score for The Terminal, Spielberg's comedy about immigrant Viktor Navorski trapped in an airport after a coup in his homeland Krakhozia, is neither. Instead, Williams creates a score infused with cultured classicism, using a clarinet, accordion and guitar used to invoke Eastern European musical traditions and the immigrant experience. Viktor's theme is impish, innocent and spirited but never hokey. Williams also created a faux national anthem for Krakhozia, one of those dour Eastern European dirges that you only hear at the Olympic games, that is pitch perfect.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)*Over the years, Williams has written numerous themes to depict child parent separation — some bittersweet (The Phantom Menace) some nightmarish (Close Encounters, Empire Of The Sun), some sweeping (Superman The Movie). But none of these themes capture the emotional anguish of parting than A.I. Artificial Intelligence. Under a string backdrop that rises and falls like tempestuous waves (glimpsed in the opening of the film), a pressing menacing melody amplifies the wrench as Monica (Frances O'Connor) dumps her 'robot son' David (Haley Joel Osment) in a forest rather than face certain destruction, discordant piano strikes heightening the unease. This is at the complete opposite end of the musical spectrum to something like Home Alone and his A.I. score is indicative of the sophistication Williams was developing as he moved into the noughties.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Amistad (1997)*The dialogue heavy Amistad, Steven Spielberg's slave mutiny drama, meant there was little place for Williams' music to count. Despite such restrictions, he still came up with a memorable score. To represent the African strands of the story, he tastefully employed regional African voices and instrumentation — the movie opens and closes with a haunting vocal that comes to represent Djimon Hounsou's Cinque. To illustrate John Quincy Adams and the American legal system, Williams uses noble brass and stately strings. The film's big anthem is Dry Your Tears, Afrika, a life affirming setting of a 1967 poem by Bernard Dadie that mixes 50 authentic voices with strident brass.

Listen to an excerpt:

The Adventures Of Tintin

First heard in: The Adventures Of Tintin: The Secret Of The Unicorn (2011)

The most American of composers, Williams went all Euro for the animated title sequence of Spielberg's take on Hergé's boy detective. In its not-to-be trusted cool evoking trench coats and peering over newspapers, it shares qualities with the opening of Catch Me If You Can (another animated title sequence), starting with sneaky woodwinds that are energised by some jazz drumming — nice! — before virtuoso harpsichord joins the party. At 0.38, we are introduced to the Tintin theme that Williams will turn heroic and swashbuckling with brass later in the score — indeed rather than a theme for the character in the movie, this feels like a tune to represent and pay tribute to Hergé's universe and legacy.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Not With My Wife, You Don't! (1966)*Williams started his film music career composing scores for a series of bedroom farces and light comedies such as How To Steal A Million, Penelope, Fitzwilly and Not With My Wife, You Don't under the soubriquet Johnny Williams. Studying music at the noted Julliard School in New York, Williams also worked as a jazz pianist and many of these scores have a lounge-y music-to-mix-cocktails-and-take-your-best-gal-dancing-at-the-Copa feel that was dominant back in the '60s. A Big Beautiful Ball plays over the titles of Not With My Wife You Don't starring Tony Curtis and George C. Scott fighting over the same girl (Virna Lisi) and is typical of Williams from this period. It might seem a world away from Star Wars and Raiders but many of the hallmarks — colourful orchestration, huge optimism and a ridiculously catchy tune — are already present and correct.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Star Wars Episode IV A New Hope (1977)*However many times you hear the Cantina Band — or Filgrin D'An And The Modal Nodes to give them full Expanded Universe props— blissing out, they still sound fresh. As make-up men such as Rick Baker mimed on set in big headed masks, Williams employed trad jazz staples — trumpet, sax, clarinet — and combined them with more offbeat instrumentation — a Fender Rhodes piano, an Arp synth and a Caribbean steel drum — to create something that is simultaneously familiar yet otherworldly. "We filtered them so it clips the bottom end of the sound," remembered Williams. "We attenuated the low end a little bit and reverbed them so that it slightly thins them out." The band's other tune, heard when Han shoots first, is mellower but a little belter too.

Listen to an excerpt:

Lapti Nek

First heard in: Star Wars Episode VI Return Of The Jedi (1983)

Between the events of A New Hope and Return Of The Jedi, much changed. A brother and sister reunited. A father and son reconciled. An Empire got crushed. But less talked about was the shift in musical tastes in the galactic underworld. In A New Hope, the sleaze of Tatooine listened to up-tempo jazz in the style of Benny Goodman. Just four years later, the scum of Jabba's palace are now grooving to the disco pop styling's of the Max Rebo band — organist Max (real name Sirulian Phantele, you can see why he changed it), singer Sy Snootles, and on lead flute Droopy McCool — and in particular their hit song Lapti Nek. The song includes lyrics written in English by Williams' son Joseph and interpreted into Huttese by Anne Arbogast who also sung on the track — in case you've always wondered, Lapti Nek translates as "Work It Out". For the 1997 Special Edition, the song was unceremoniously dumped for the vastly inferior Jedi Rocks. The less said about that the better.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: 1941 (1979)*It is no secret that Steven Spielberg has always dreamed of making a huge Hollywood musical. As such, trace elements have occurred throughout his work; with Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom, he opened with a breathtaking staging of Cole Porter's Anything Goes translated into Mandarin Chinese that is straight out of the Busby Berkeley playbook ("I love Cole Porter," said Williams, "and I got the biggest kick out of doing that pastiche, with a female chorus and antique sax.") Yet Spielberg's biggest expression of his passion for musicals came with 1941, mounting a stunningly choreographed Jitterbug dance contest that develops into an equally balletic chase before exploding into a full-scale riot. Musically, the Robert Zemeckis-Bob Gale script outlined the dance would take place to Benny Goodman's 8 minute 1937 recording of Sing, Sing, Sing, an epic demonstration of big band virtuosity, and Spielberg used the song as playback for the dancers. Yet during post production, the cutting rendered the song unworkable with the images and Williams was brought into compose a parody ("I called my piece Swing, Swing, Swing — a little play on words thing there.") The result is just joyous, full of jumpin' clarinet, blarin; trombones, pulsatin' tom toms all played by a swingin' band yet full of musical accents for sync points that give it an almost cartoon-y feel.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1984)*Steven Spielberg described the chant that accompanies the Temple Of Doom as the "only music effective enough to knock the hat off of Indiana Jones' head." By the time we get to this point in the movie, we are too far into the subterranean depths to hear the Indiana Jones theme, all the familiar comforting themes are out of earshot. Instead, as Mola Ram (Amrish Puri), high priest of the Thuggee cult, prepares to sacrifice a helpless victim to the god Kali, we are subjected to a Sanskrit choral chant, booming timpani and metal percussion that eventually find heart racing form, building pace and intensity to an ear shattering climax. Recorded before the shoot it became producer Frank Marshall's job to make sure the on-set drummer kept time with the playback as the actor had a serious lack of rhythm —the Making Of footage is hilarious. Unique within the Indiana Jones musical canon, Williams returned to the idea of a Sanskrit chant for The Duel Of The Fates in Episode I.

Listen to an excerpt:

Plowing

First heard in: War Horse (2011)

Introduced in the first War Horse trailer, Williams theme to represent the growing bond between farm boy Albert (Jeremy Irvine) and farm horse Joey (Finder) is amongst the loveliest stuff he's produced in ages. Powerful and majestic, it does that Williams (and Spielberg) thing of feeling grand and intimate all at the same time. When the melody rises through the horn section, it's a hair-stands-up on-end moment.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Superman The Movie (1978)*Few composers can mark a rite of passage like Williams. As Clark Kent discovers the call of a generative green crystal and realises he must leave Smallville to fulfil his destiny, Williams takes a small Family/Smallville theme the score has been noodling with and turns it to something grand and gorgeous as a mother and son part ways.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: The Cowboys (1972)*Directed by Mark Rydell, The Cowboys was one of the last cattle drives for John Wayne as a grizzled rancher who, after his cowhands go off in search of gold, enlists eleven schoolboys to trail his herd to market. Williams music, kicking off with blazing horns, effortlessly evokes the wide-open spaces of the old west and the thrill of a cattle drive but also pulls in an almost nursery rhyme feel to the tune to identify his juvenile cowpokes. It's a fun, good natured piece that proved important in Williams' career: along with The Reivers, it was the music that put Williams front and centre in the mind of Steven Spielberg when he was considering composers for his debut, The Sugarland Express.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Born On The Fourth Of July (1982)*Williams' first collaboration with Oliver Stone is symphonic work on the biggest canvas. As with their next collaboration, JFK, the music is suffused by a real sense of America yet also full of Stone's sadness and regret, this time reflecting his feelings about Vietnam and the fallout for the veterans after they returned home. From the very first note, this contains some of Williams' most impassioned music, the emotion coming through in everything from the massed string section to the solo cornet. Williams has used music describe some of the key wars of the 20th Century but few of his scores attain the level of tragedy and loss-of-innocence as this.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Midway (1976)*A forgotten picture, Midway is a World War II movie dramatising the key battle in the Pacific war starring what used to be called An All Star Cast (Charlton Heston, Henry Fonda, James Coburn, Toshiro Mifune, Robert Mitchum). In his younger days, Williams was a conductor and arranger for the US Air Force Band and his main theme here is the film's most lasting legacy, an upbeat military fanfare that plays little part in the movie but stands on its own as the kind of bright dramatic, patriotic march beloved of High School bands on US football fields. Bizarrely, this was released as a single in Japan, a 45 that remained the only commercial recording of the theme for ages.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: 1941 (1979)*Or the comedic flipside of the Midway March. Williams' main theme for Spielberg's WWII home invasion comedy walks a thin tightrope between bare-faced dramatics and tongue in cheek satire and it's often hard to tell them apart. For Williams, the march "has a kind of jazzy, almost Southern swagger to it…and it's a little bit impertinent in character" and the theme, which gets regurgitated throughout the score provides much of its nutty energy and gung ho spirit — on the album it is augmented with cannon fire and John Belushi ("My name is Wild Bill Kelso and don't you forget it"). During the recording, Spielberg reputedly ran home to get his clarinet and joined in "to make sure the end result was ragged enough" and at the end of the session, Spielberg served champagne to the entire orchestra to celebrate. The movie might be low in the Spielberg canon but the March retains a special place in his affections. "Still to this day, the best march John ever wrote was 1941," Spielberg remembered. "I actually prefer that march to the march he wrote for Raiders Of The Lost Ark."

Listen to an excerpt:

Hymn To The Fallen

First heard in: Saving Private Ryan (1998)

Part of the job of a composer is to "spot" the movie, work with the director and music editor to decide which scenes need musical enhancement and which moments can live without it. For Saving Private Ryan, Spielberg and Williams, not wanting to hype the action, decided that the battle scenes should play with real combat sounds, leaving the composer to add emotional gravitas to the more reflective scenes such as Captain Miller (Tom Hanks) staring out over D-Day's carnage or secretaries typing up letters of bereavement for soldiers' families. For the end credits, Williams composed Hymn To The Fallen, an elegy for those who perished in combat that is restrained and respectful, starting from a single snare drum, building through the whole orchestra and choir, then diminishing to a note of quiet dignity.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Schindler's List (1993)*Williams won his first Academy Award for adapting the musical Fiddler On The Roof and that familiarity with Jewish musical traditions must have come into play when the composer was working through Schindler's List. His second theme for Schindler's, Remembrances, served to commemorate the Shoah from a modern perspective and is infused with an over-riding respect for Hebraic history. While the string arrangement offers a lush borderline romantic feel, at Spielberg's suggestion, Williams enlisted violin virtuoso Itzhak Perlman who, on the arrangement for solo violin, plays with a deep-felt sincerity and astonishing sensitivity. "The subject of the movie was so important to me," recalled Perlman, "and I felt that I could contribute simply by just knowing the history, and feeling the history, and indirectly actually being a victim of that history."

Listen to an excerpt:

Toy Planes, Home And Hearth

First heard in: Empire Of The Sun (1987)

For Spielberg and Williams, Empure Of The Sun represented a big stepping stone towards Schindler's List. There's a lot of dark musical material in the underrated WWII movie. Williams charts Jim Graham (Christian Bale)'s journey from a life of privilege in Shanghai to the deprivation of a WWII camp, quoting nostalgic Chopin to suggest Jim's cosseted childhood before launching into tones of panic, anxiety and abandonment. Yet Williams also comes up with a main theme for Jim that is heartbreaking in its minor gentler modes but can send the spirit soaring in its lush epic arrangement.

Listen to an excerpt:

The Force Theme

First heard in: Star Wars Episode IV A New Hope (1977)

A huge part of Williams' genius is his ability to add different colours and moods to his basic motifs to express different parts of the story. For New Hope, Williams created a theme that seems to stand in for Kenobi but is also utilised to suggest both the Old Republic and the Force itself and is amongst the most malleable, versatile themes Williams has ever created. We get a noble, mysterious take (the arrival of Kenobi), an urgent dramatic take (Luke speeds to the burning homestead), a mournful iteration (Leia comforts Luke after Ben's death), an untethered mystical version (as Luke hears Ben tell him to use the Force) and a stately regal version (our heroes collect their medals) that is perhaps a reminder of the values Kenobi represented.

Listen to an excerpt:

Yet its most famous iteration has nothing to with Obi-Wan at all. Williams had originally scored Luke staring out into Tatooine’s twin suns with Luke’s theme yet Lucas asked the composer to switch it for Ben’s music. The result is perhaps the most reflective, moving moment in the whole saga.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Hook (1991)*The Lost Boys are the Jar Jar Binks of Hook, often pointed to as indicative of all that is wrong with the film, day-glo ruffians on skateboards that are the antithesis of what J.M. Barrie envisaged. Still if there is an organized campaign against Rufio and co., John Williams didn't get the memo. For not only did Williams write them an enjoyably boisterous theme to cover their pursuit of Peter in Neverland, he also gifted them a glorious theme for their Neverfeast — it may be music for a food fight but it sounds like something composed for an English costume drama, formal, majestic and splendid.

Listen to an excerpt:

*First heard in: Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981)*Over the eight minutes of screen time it takes Indiana Jones to steal a horse, pick off the Nazis one by one, get thrown through the windscreen and under the truck, climb back in the side window to take control of the steering wheel and then, after all that, hold his arm while wincing in pain, Williams is there every step off the way, providing propulsive rhythms to create a tempo that never flags and a tapestry of themes to plot the rise and fall of Indy's fortunes. Spielberg pays tribute to the cue here{

Listen to an excerpt:

Saying Goodbye

First heard in: E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

"I've always felt that John Williams was my musical rewrite artist," says Spielberg. "He comes in, sees my movie, rewrites the whole thing musically and makes it much better than I did. He can take a moment and just uplift it. He can take a tear that's just forming in your eye and cause it to drip."

Nowhere is this ability more prevalent than at the climax of E.T. From the point where Elliott and Michael steal E.T. away in a van, through to the BMX chase and flight, the tearful goodbye to the spaceship leaving a rainbow trail, E.T. is pretty much just images and music with dialogue kept to the barest minimum. In theory, it should be a composer's dream but….

"I was having a very difficult time with the orchestra," said Williams. "I would make a good take for the first five but then be off for the next two cues. I remember it so well. Steven coming up to the podium and saying 'I will take the movie off the screen so you can just play the music with the orchestra with it's natural phrasing, the way it ebbs and flows and then conform the film to what is the best musical performance'. That is very unusual. So when we had the music that had the most lift and exultation at the end of the film, Steven laid the music track against the film and made a few editorial adjustments. I think part of the reason the film has such an operatic sense of completion, a real emotional satisfaction maybe the result of the wedding of these musical accents with Steven's film editing."

Be it the brass statement that accompanies "I'll be right here" to the return to the Flying theme as the door closes on E.T.'s spacecraft, Williams' music is a major reason why the goodbye between a boy and alien brings a lump the size of an orange to the throat. This score as a whole is a strong contender for his greatest overall work and deservedly earned him his fourth Oscar.

Listen to an excerpt:

***There is only one way to conclude the 80th birthday celebrations of the world's greatest movie music composer — with a party. Happy birthday, maestro!

Listen to an excerpt:

For more music celebrating John Williams’ 80th birthday:*