Hayao Miyazaki is arguably the greatest living animation director, the Japanese Walt Disney — though he’d not thank you for the title. With Studio Ghibli's eleventh feature, Arrietty, about to hit our screens, Empire is proud to relive the studio's filmography with the man who continues to preside over it so gloriously. Prepare for 30 years of unparalleled magic...

The respect that animators the world over have for Hayao Miyazaki is hard to overstate. Pixar chief John Lasseter claims he’s “one of the greatest filmmakers of our time”, and the fact that Lasseter now oversees all Miyazaki’s English dubs, attracting such talent as Billy Bob Thornton, Christian Bale, Lauren Bacall and Liam Neeson to voice them, should suggest he’s not exaggerating. Miyazaki is a high fantasist as comfortable dreaming up steampunk action-adventures as he is intimate child dramas, inter-war aerial romps, post-apocalyptic wastescapes, monster-populated spirit worlds, or the deep, violent past of his own homeland, Japan. His own producer, Toshio Suzuki, also a Ghibli board-member, simply describes him as “a genius”. And when Empire meets the 68 year-old director for a rare interview, we suspect he may just qualify as an eccentric one.

Studio Ghibli consists of three unassuming buildings located in the quiet suburb of Koganei in western Tokyo. We’ve arrived at Miyazaki’s private office building, a few streets down from the studio proper, where we find the man himself in his central office, a large but welcoming space whose two salient features are a grand piano and a wood-burning stove, which Miyazaki keeps topping up with timber during our near-two-hour discussion of his work...

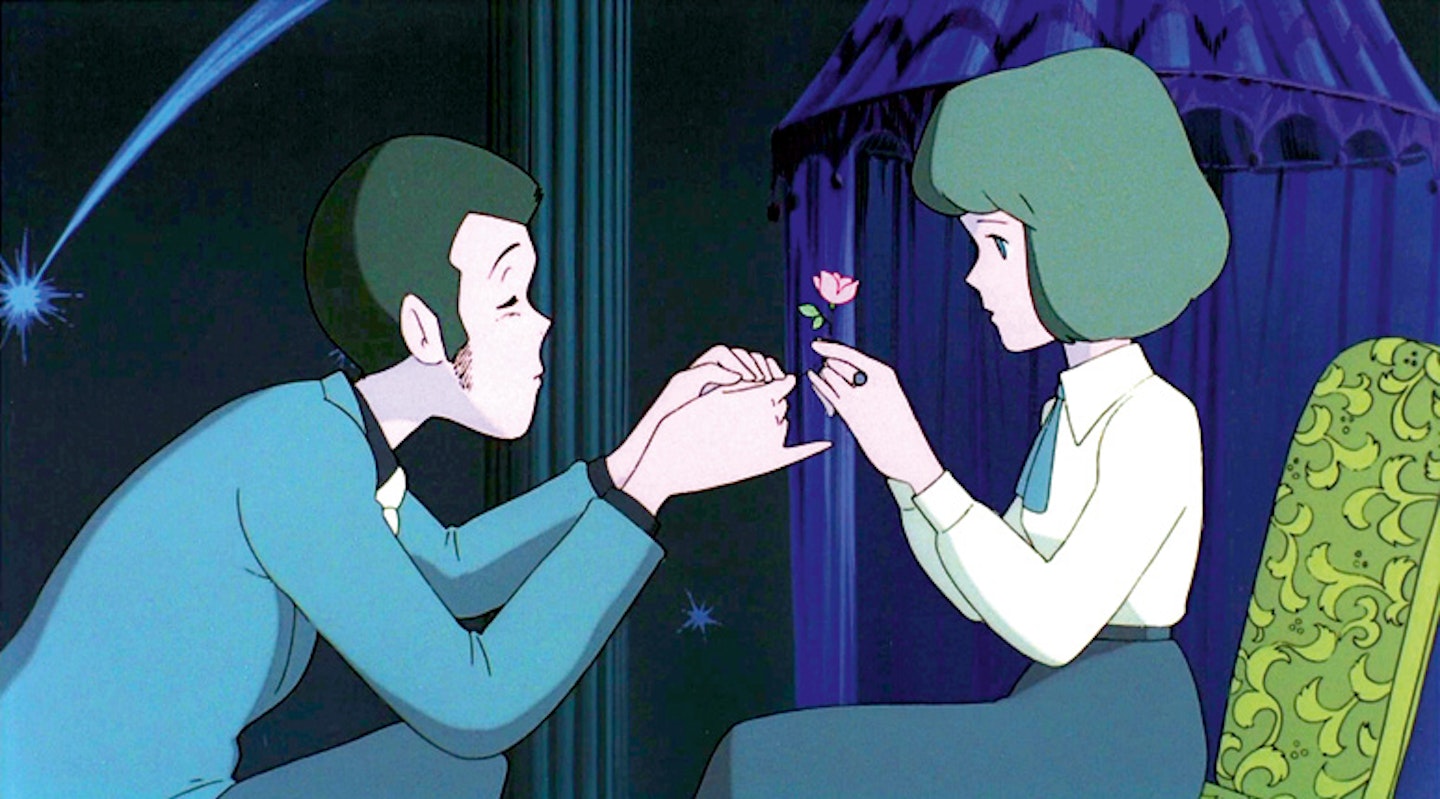

Miyazaki’s cinematic debut stands apart from the bulk of his work, given it’s his only movie as, effectively, a director-for-hire. Not a sequel, rather a feature spin-off of TV show Lupin The 3rd (itself derived from Monkey Punch’s comic book, or manga), on which Miyazaki worked, the film follows the continuing misadventures of the titular rogue — grandson of Maurice Leblanc’s Arsène — as he embroils himself in the affairs of the nefarious Duke Of Cagliostro. While this enthusiastic, irreverent romp doesn’t feel like ‘pure’ Miyazaki, it does revel in its Riviera setting, displaying a love for European architecture and landscape that’s since defined much of his work (Laputa: Castle In The Sky, Porco Rosso, Howl’s Moving Castle).

Miyazaki on Miyazaki “Actually, I didn’t know European landscapes and architecture very well back then. So inside the castle I set myself a rule: always try to make the same space come up twice. If the character goes there once, then the character will go back to the same place again. It was like a game, and that was how I created the setting: ‘Here’s two lakes, a castle, there’s a Roman aqueduct...’ And then I thought, ‘Yes, now I can make a film on this!’ I just wish that I could have done it much, much better!”

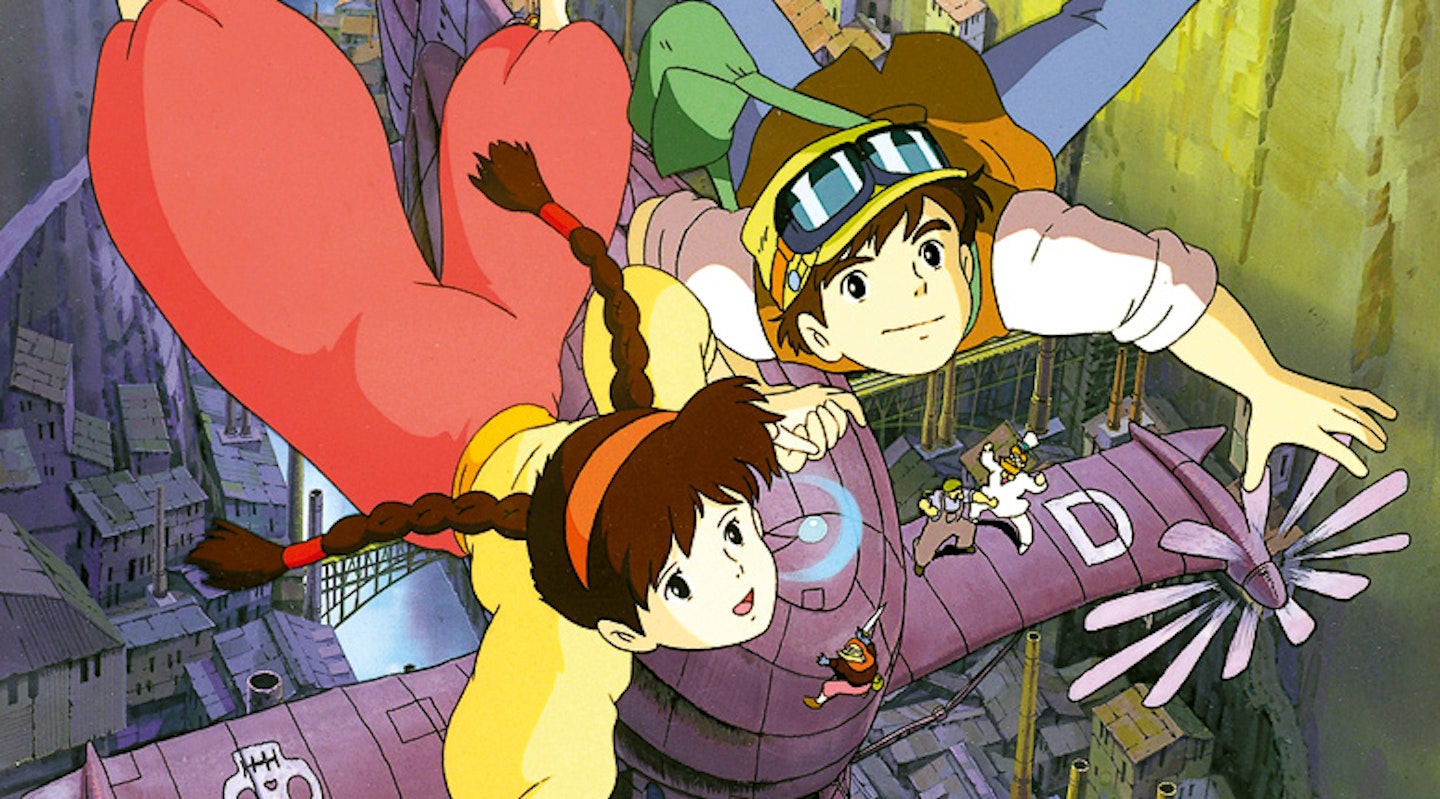

Laputa: Castle In The Sky (1986)

*Miyazaki’s third feature, and Ghibli’s first, is a high-flying adventure set in an alternative-reality steampunk 19th century England where the stratosphere is home to comical sky pirates, flying robots and — spot the Swift reference — mysterious floating castles. Its cult appeal runs deep yet it was not a big success, something Miyazaki feels is down to the fact he chose a young boy from a mining village (Pazu) to be its hero. Almost every Miyazaki protagonist since has been female. *

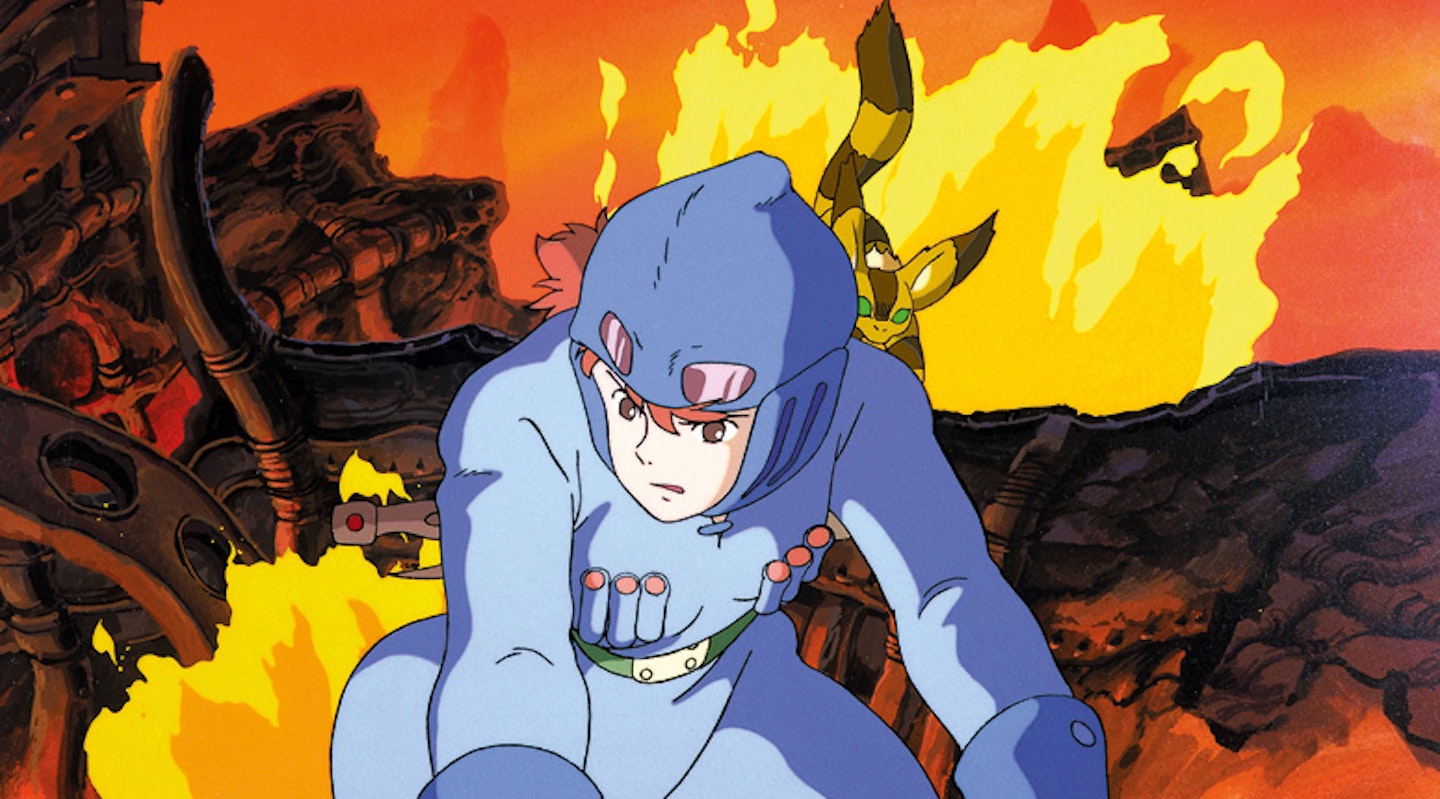

Nausicaä Of The Valley of The Wind (1984)

*Based on Miyazaki’s own complex manga (which he didn’t finish until 1994!), Nausicaä is a remarkable work, set in a post-apocalyptic world swathed in poisonous gas, the bickering remnants of humanity sharing the Earth with giant insectoids. It’s eerily beautiful, with a powerful, young female lead character — now a Miyazaki mainstay — and is not the last of his films to resound with a clear environmental message (the mercury-pollution of Minamata Bay was his main inspiration). Sadly, its rough treatment by its American distributor, which slashed the running time and renamed it Warriors Of The Wind, meant it remained largely undiscovered abroad, making Miyazaki and his producer, Toshio Suzuki, deeply sceptical about foreign treatment of their works. *

Miyazaki on Miyazaki “The original manga was written when I had no job in animation — I had a lot of time to myself, so I tried to make a comic that couldn’t be made into animation. And then later I had to make it into a film, so I was in deep trouble! There were a lot of things I just didn’t know how to do back then, how to make it work. But I still had to make it.

“Why did the lead character have to be female? Well, it doesn’t look truthful if the guy has power like that! Women are able to straddle both the real world and the other world — like mediums. In the oldest form of the Cinderella story, she was able to travel freely to the other world through the hearth: that’s what empowered her. It isn’t the swordplay that Nausicäa is good at, it’s that she understands both the human world and the insect world. No animals feel danger in approaching her; she’s able to totally erase her sense of presence, existence. Males, they are aggressive, only in the human sphere — very shallow! (Laughs) So it had to be a female character.”

Considered Miyazaki’s masterpiece, and certainly his best-loved work, its big-grinned forest-spirit star forming the basis of a huge merchandising empire in Japan. An intimate family tale set during one summer in ’50s rural Japan, it boasts astonishing attention to detail and delicate characterisation of two young sisters, Mei and Satsuki, who have moved with their father to a new house while their mother is away in hospital (Miyazaki’s own mother suffered from spinal tuberculosis). Few films better capture the joyful power of unfettered childhood imagination.

Miyazaki%20on%20Miyazaki**%20%E2%80%9CI%20can%E2%80%99t%20make%20films%20that%20are,%20you%20know%20%E2%80%94%20slay%20the%20villain,%20everybody%E2%80%99s%20happy.%20I%20can%E2%80%99t%20make%20those%20kinds%20of%20films.%20I%20think%20that%20when%20children%20become%20three%20or%20four%20years%20old,%20they%20just%20need%20to%20see%20Totoro.%20It%E2%80%99s%20a%20very%20innocent%20film.%20I%20wanted%20to%20make%20a%20film%20in%20which%20there%E2%80%99s%20a%20monster%20that%E2%80%99s%20living%20next%20door%20but%20you%20can%E2%80%99t%20see%20it.%20Like%20when%20you%20walk%20into%20a%20forest,%20you%20sense%20something.%20You%20don%E2%80%99t%20know%20what%20it%20is,%20but%20there%E2%80%99s%20a%20certain%20presence.%20That%E2%80%99s%20happened%20to%20me%20many%20times,%20you%20know?+I+recently+spent+two+months+in+a+big+old+house%2C+alone%2C+on+top+of+a+cliff+by+the+sea%2C+and+I+would+be+in+one+room+but+it+felt+like+there+were+other+people+living+in+the+other+rooms.+When+I+would+go+out+for+a+walk%2C+I+thought+they+would+be+lonely%2C+so+I+turned+on+my+radio+to+entertain+them+while+I%E2%80%99m+out%21+%E2%80%9CPlease%2C+feel+free+to+enjoy+my+music%21%E2%80%9D+%28Laughs=&auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

“During production when it’s very hard, and the staff are suffering, there is a sort of smell, like a bad scent. People are drawing and animating and then everybody goes home and we open the windows to change the air. Now, that scent doesn’t go away — it’s this bad feeling I can sense. I think maybe small infants can feel and receive it more directly than adults can. At the same time they’re very easily fooled with smiles (laughs) — you just have to show them teeth and they’re happy!”

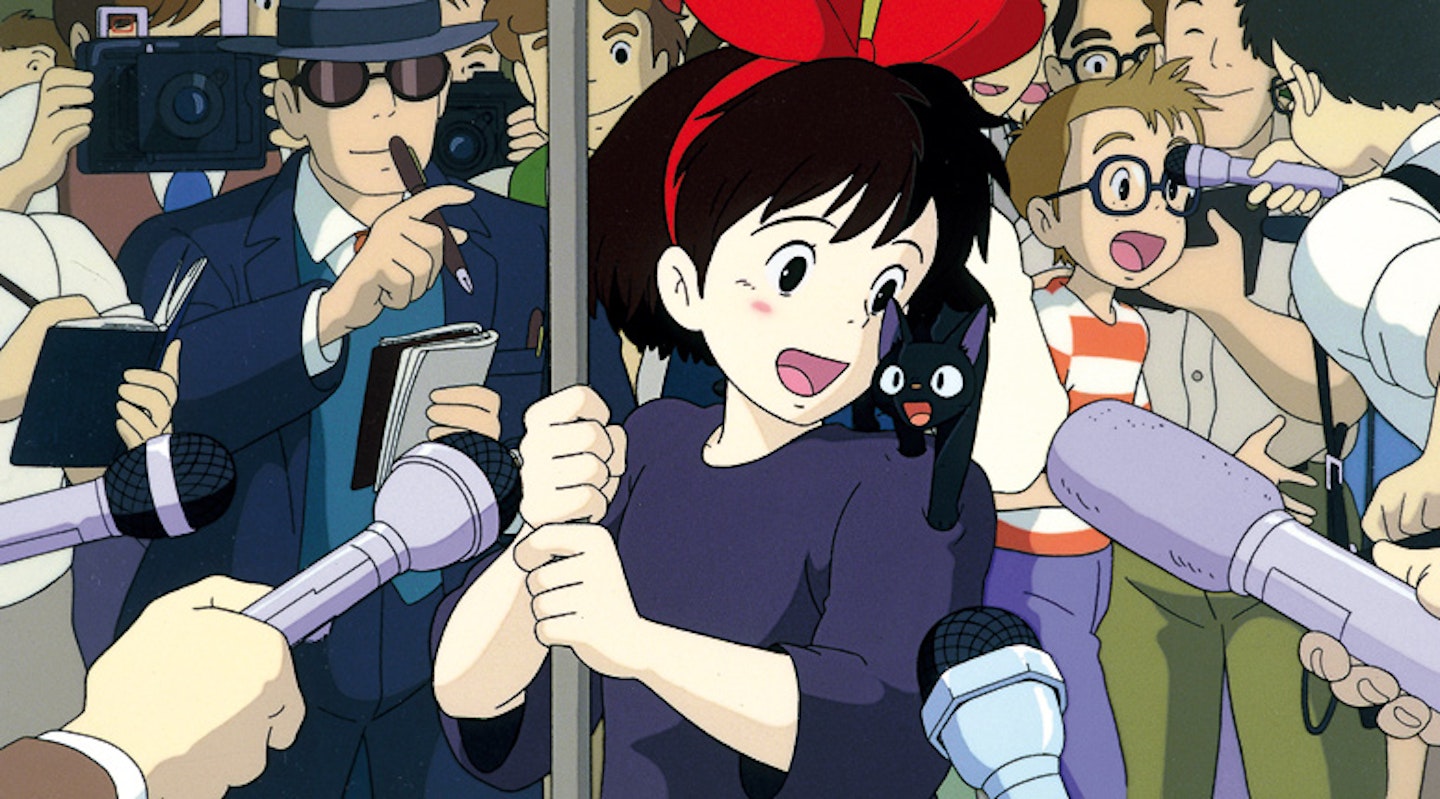

Kiki's Delivery Service (1989)

*Based on the books by Japanese writer Eiko Kadono, this is Miyazaki’s first true literary adaptation, although, as with all his others since, it bears little resemblance to the original. Aimed at teenage girls, it is set in a modern world where witchcraft exists, and where young witches have to leave home at the age of 13. We follow the insecure Kiki and her sarcastic cat, Jiji. As with Totoro, there’s no bad-guy figure, no conflict; Kiki’s adventure is simply one of discovering self-confidence. *

Miyazaki on Miyazaki “I was inspired by the struggle of young cartoonists to find work. It’s not simply about making money and earning a living — everybody does that. It’s about living your own life: how do you assert your individuality in this world? I think that’s what everybody was concerned about when we made that film. I think if we made the film now it would turn out different. So Kiki’s okay as a witch, but Tombo (the aeroplane-obsessed boy whom Kiki befriends) has to pass the exam, go to college, find a job, and then go to Kiki and ask, ‘Can you please go out with me?’ And Kiki, I’m sure, maybe she’s doing her delivery service and meeting people and she’s enjoying life and being a little mad. But nobody wishes Kiki would found a huge delivery service company and become its president. Nobody wants to see that! Maybe in China, Kiki would found a huge, delivery-service company... (Laughs) But not in Japan.”

Porko Rosso (1992)

*If Totoro is Miyazaki’s movie for three-year-olds and Kiki for teenage girls, then Porco Rosso is for middle-aged men (most importantly Miyazaki himself). Its protagonist, Marco Pagott, is a mercenary collecting bounties for pirates in the skies above the Adriatic during the ’20s. It’s this film, more than any other, which reveals Miyazaki’s love for aircraft (his father’s firm was Miyazaki Airplane; Ghibli is named after an Italian fighter plane). And, appropriately, its origins are as in-flight entertainment... *

Miyazaki on Miyazaki “Japan Airlines needed a short film to screen during their flights. At first, we weren’t up for it — when we said we’d like to show dogfights, we thought they’d say no. But then they said, ‘That’s fine’ (laughs). Really, it was based on my hobby, and I wanted to make something light. But then Yugoslavia collapsed and all these conflicts broke out in Dubrovnic, Croatia and the islands which were my setting. Suddenly in the real world it became a place where battle was happening. So then Porco Rosso became a more complicated film. It was a very difficult film and I was so disappointed that I’d made something for middle-aged men, because I’d been telling my staff always to make films for children and then what did I do?! Actually, the children came to see it and gave me the next chance to make another film. So when I started my next film, I was able to finally free myself of the curse of Porco Rosso!”

*Princess Mononoke was Ghibli’s most expensive movie, and went on to become Japan’s biggest-ever grossing picture. Following a young warrior mortally cursed by a diseased boar-demon, it takes us deep into Japan’s primeval forest, as its gods of nature resist humanity’s industrial progress. Arguably unsuitable for Ghibli’s younger audience, it features brutal combat scenes and monstrous mutations, entwining the theme of aborted innocence with its overt environmental concerns.

Miyazaki on Miyazaki “It was a huge risk, totally different from when I was making Kiki. I’d had that experience with Porco Rosso, the war happened (in the former Yugoslavia), and I learned that mankind doesn’t learn. After that, we couldn’t go back and make some film like Kiki’s Delivery Service. It felt like children were being born to this world without being blessed. How could we pretend to them that we’re happy?

“I think I really exhausted the animation staff with this film. I knew that was gonna happen, but felt that we had to do this. But when I finished, I didn’t understand it: ‘What did I make?!’ At first I decided, ‘This is something children shouldn’t see,’ but in the end I realised, ‘No, this is something that children must see,’ because adults, they didn’t get it — children understood it. So again children helped me out. Again I was able to make the next film!”

Howl's Moving Castle (2004)

Despite the pain of making his last two films, accompanied by hints that he was going to retire, Miyazaki returned to the drawing board with his second literary adaptation, this time of Diana Wynne Jones’ Howl’s Moving Castle. Like Mononoke, it centres on a cursed protagonist, this time young wallflower Sophie, aged by a witch into an old crone. Like all Miyazaki’s films it teems with astonishing detail, but is his least focused story and features his least satisfying denouement.

Miyazaki on Miyazaki “Diana Wynne Jones... I was snared in a trap by her. Her story has great reality for the female reader, but she doesn’t care anything about how the world is set up. And all the men in her novels are like her husband: kind of sad, standing there quietly (laughs). And magic without any rules… you know, it kind of loses control. But I didn’t want to make a movie that explains the rules. That’s just like making a video-game. So I made a film that doesn’t explain the logic of the magic and everybody got lost! (Laughs)

“We don’t know why, but it had very extreme reactions: people who really loved it, and people who didn’t understand it. It was a horrible experience. I’ve been so tired out since Princess Mononoke. And to continue in this complicated direction, I thought, ‘We can’t do this anymore!’ Mononoke, Spirited Away, Howl... We decided to change direction. And that’s why we did Ponyo the way we did.”

Spirited Away (2001)

Sixteen years after the foundation of Ghibli, Miyazaki finally found success in the West. Heaped with critical praise, and also an Oscar, his colourful tale of a sulky girl named Chihiro trapped in a world of spirits, demons and gods after her parents are polymorphed into pigs proved pleasantly flummoxing to its Western audience. It takes a sudden twist of direction midway through, shifting focus from Chihiro to hungry spectre No-Face, then sending the girl on a mission to absolve dragon/boy Aku rather than freeing her parents. This was less due to Miyazaki’s grand plan than the need to solve a problem he’d made for himself…

Miyazaki on Miyazaki “There were these girls I’d known since they’d been babies. They were daughters of my friend. And they grew to be ten and 12 and I said, ‘I can distance myself from them now, they’re going to blossom into women and I don’t have to play uncle anymore.’And I was wondering how they would live from now on, and I thought of Spirited Away as a gift to those girls.

But it was a hard film to make. After I started production, the key animator, the art director and the producer came out on holiday with me and we had this blackboard and tried to draft out which direction the film was going in. I explained, ‘I think we’ll be able to do this kind of story, with this kind of ending,’ and then Suzuki-san (the producer) said: ‘Ah. That will take three hours. I don’t want to make a three-hour movie!’

I%20said,%20%E2%80%98Okay.%20I%E2%80%99ll%20make%20the%20story%20shorter.%E2%80%99%20And%20there%20was%20No-Face%20%E2%80%94%20he%20just%20happened%20to%20be%20a%20bystanding%20character.%20We%20decided,%20%E2%80%98Oh,%20let%E2%80%99s%20use%20that%20one,%E2%80%99%20so%20that%20character%20suddenly%20came%20and%20we%20were%20able%20to%20make%20a%20sort%20of%20short%20two-hour%20movie%20(laughs).%20But%20the%20bath-house%20and%20the%20old%20lady%20that%E2%80%99s%20there,%20and%20the%20gods%E2%80%A6%20I%20like%20that%20kind%20of%20world.%20They%E2%80%99re%20very%20intriguing.%20That%20other%20world%20has%20much%20depth%20and%20there%E2%80%99s%20a%20lot%20of%20different%20kinds%20of%20people%20inhabiting%20it%20%E2%80%94%20that%E2%80%99s%20what%20I%20like%20to%20work%20with.%20It%E2%80%99s%20not%20a%20small%20contained%20world,%20it%E2%80%99s%20actually%20a%20world%20that%20stretches%20out,%20a%20place%20that%20it%E2%80%99s%20normal%20that%20when%20it%20rains%20there%E2%80%99s%20a%20sea%20the%20next%20day%E2%80%A6%20So%20that%E2%80%99s%20why%20Spirited%20Away%20evolved%20into%20that%20kind%20of%20film.%20And%20it%20was%20so%20much%20pain%20and%20care%20and%20labour%20I%20don%E2%80%99t%20know%20why%20I%20do%20these%20things!%E2%80%9D%20(Laughs?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

*Miyazaki’s spin on The Little Mermaid hoves close to My Neighbour Totoro, unapologetically aiming at his youngest audience since 1988. But with its luxuriant hand-drawn style it has a warmth and palpability that makes it feel unique among modern animated features. It also takes Miyazaki to new territory: where he usually takes to the skies, here he dives deep into the ocean, which rebellious young goldfish-girl Ponyo seeks to escape for the joys of terrestrial life with resourceful five year-old boy Sosuke.

Miyazaki on Miyazaki “I have always dreamed of making a film with the sea as a motif, but animating the waves is really hard, so I wasn’t able to do that up to now. I decided to change the way of animating, and had a change of thought: that the sea is actually a living thing. Of course, it took courage to draw eyes on it! But a lot of the staff thought it was interesting so I thought, ‘Oh, okay, it works!’

“I also thought maybe we’d travelled too far away from children, that we should go back to the five-year-olds. But I can’t go back and make the same innocent ‘Totoro’ kind of film. So I put in more complex things. If you want to make something innocent, a shorter film is better. It’s not a good thing to make something very long for small children. For a long time, Suzuki-san had been saying, ‘Why can’t you make your films shorter?!’ But I have to make my films more complex, so this is 101 minutes.

“The part I love most about Ponyo is the end credits. There’s no job titles: I just put everybody who was involved in Japanese alphabetical order. So the big investors and the small little studios, they’re all treated equally in the end credits. And we don’t know where the producer is, where the director is. We even have the three stray cats that live round the studio — we even have their names on it, too!”

Beyond Miyazaki

Studio Ghibli's other feature films...

WORDS ANDREW OSMOND

Grave Of The Fireflies (1988)

The sad one. Indeed, Empire’s own Simon Braund rated it one of the ten most depressing movies ever made — which makes it all the stranger that it was released as a double bill with My Neighbour Totoro. Yet, if you accept that this hard-hitting drama — about a young boy and his infant sister trying to survive in wartime Japan — won’t end well, then it has moments of warmth, humour and beauty. Directed by Isao Takahata, Miyazaki’s senior colleague since the ’60s. - - - - - -

Only Yesterday (1991)**

The one never released on US DVD — although thanks to Optimum, it’s available in Britain. Evoking an introspective arthouse picture, it’s really two films intertwined: one is a sweet memoir of a girl’s childhood in ’60s Japan; the other has her grown-up self holidaying on a farm and finding her nation’s lost identity. Director Takahata leaves it to us to fit the halves together.

Ocean Waves (1993)

The one made for TV (its Japanese name translates to I Can Hear The Sea). Unusually for Ghibli, this naturalistic high school drama is told from a boy’s viewpoint, as the protagonist becomes intrigued by a beautiful female transfer student. It’s directed by Tomomi Mochizuki, who’d worked on ‘young love’ anime sagas such as Maison Ikkoku and Kimagure Orange Road. - - - - - -

**Pom%20Poko%20(1994?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

The one where cartoon animals sport big testicles (really!). Takahata’s third Ghibli film shows tanuki — Japanese wild dogs with magic shape-changing powers — fighting against the destruction of their habitat. Like Watership Down, the film mixes animal folklore with political beast-fable (the tanuki are like squabbling eco-warriors). It’s deliberately digressive, a first draft of an imagined history.

Whisper Of The Heart (1995)

The one where the heroine sings Country Road. Miyazaki storyboarded and his protégé, Yoshifumi Kondo, directed the tale of a perky schoolgirl who flowers into love and artistic endeavour, portrayed with an affection that never cloys. Tragically, Kondo died soon after its release, aged just 47. - - - - - -

My Neighbours The Yamadas (1999)

The one that looks like no other Ghibli film. Takahata’s most recent feature adapts a newspaper strip about a family’s daily mishaps, animated with simple designs and soft pastels. Large sections consist of one gentle gag after another (imagine leafing through a compendium of Peanuts), punctuated by haikus and the occasional spectacle, such as a barnstorming performance of Que Sera Sera. - - - - - -

The%20Cat%20Returns%20(2002?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

The non-Miyazaki with the best dub, featuring Anne Hathaway, Cary Elwes, Peter Boyle and Tim Curry. Hathaway’s scatty schoolgirl saves a cat and is whisked to a magical feline kingdom. Luckily there’s a courteous cat, the Baron (Elwes), to protect her. A kind-of sequel to Whisper Of The Heart, it was directed by Hiroyuki Morita. - - - - - -

Tales From Earthsea (2006)

The controversial one. Ursula Le Guin’s fantasy books were a big influence on Miyazaki, but this adaptation went to his son, Goro. The widely reported conflict between the two overshadowed the film, which daringly makes its protagonist a murderer caught up in a war between wizards.