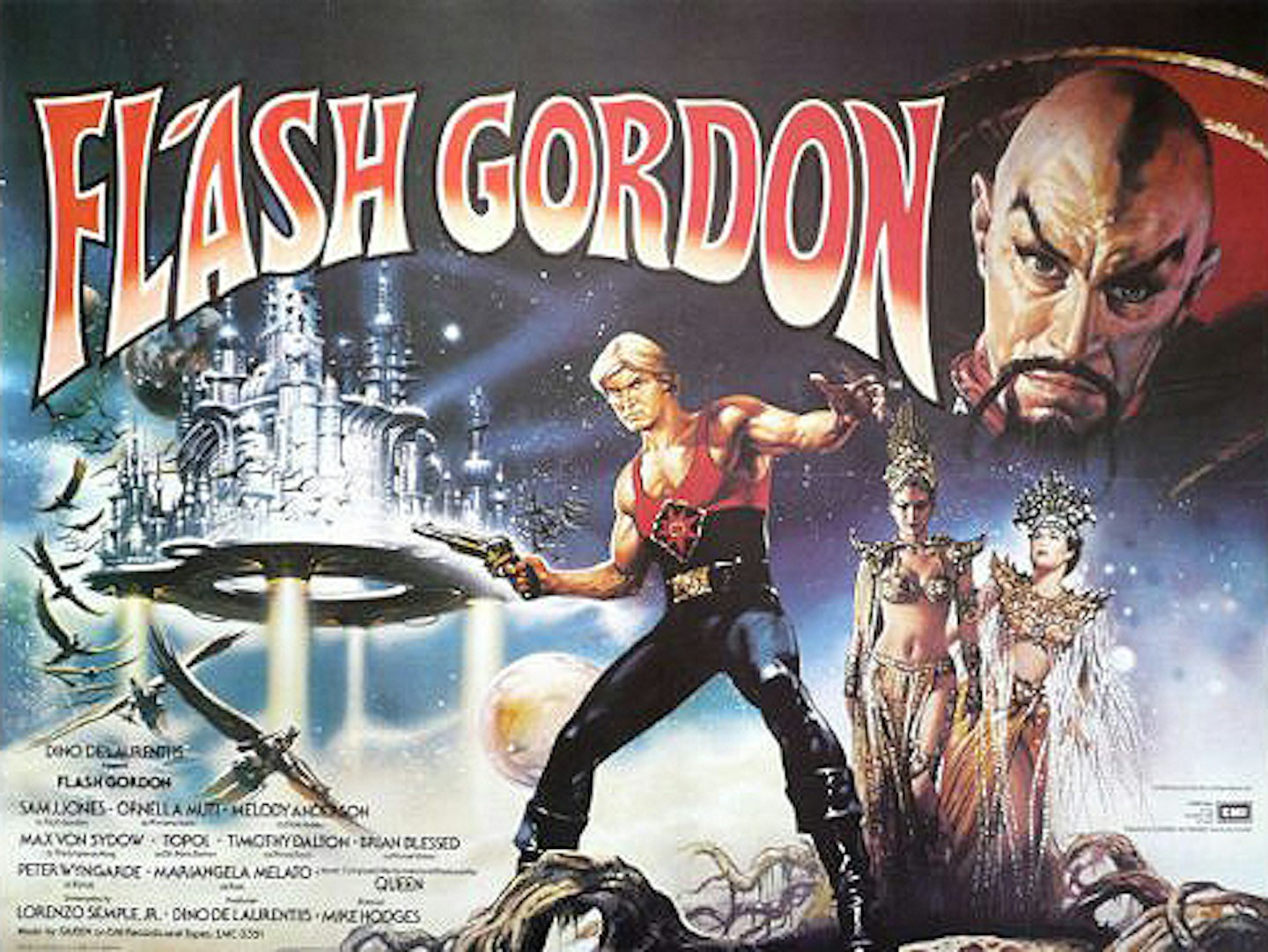

With intergalactic villains, swashbuckling heroes and silver-screen romance, Flash Gordon was pretty much made for the big screen. But even with a charismatic producer, big budgets and a pick of hot directors, Alex Raymond's musclebound creation had an arduous journey to the cinema. As J.J. Abrams' Star Wars: The Force Awakens sweeps all before it, Empire tells the fantastic tale behind one of its key inspirations.

Sometime in early 1979 Mike Hodges, the British director of The Terminal Man and Get Carter, found himself aboard Concorde flying from Heathrow to New York. As the world’s first, and apparently last, supersonic airliner levelled out of its alarming climb and approached its cruising speed of Mach 2, the besuited business tycoons aboard sipped their G&Ts and began to pull out sober reading matter for the three-and-a-half-hour flight. Hodges, though, had something very different to occupy his time. “After an almost vertical takeoff, they opened their briefcases and took out computer readouts or whatever,” Hodges remembers. “I, on the other hand, took out the bumper album of the original Flash Gordon strips. They probably thought I was retarded.”

The madness had begun...

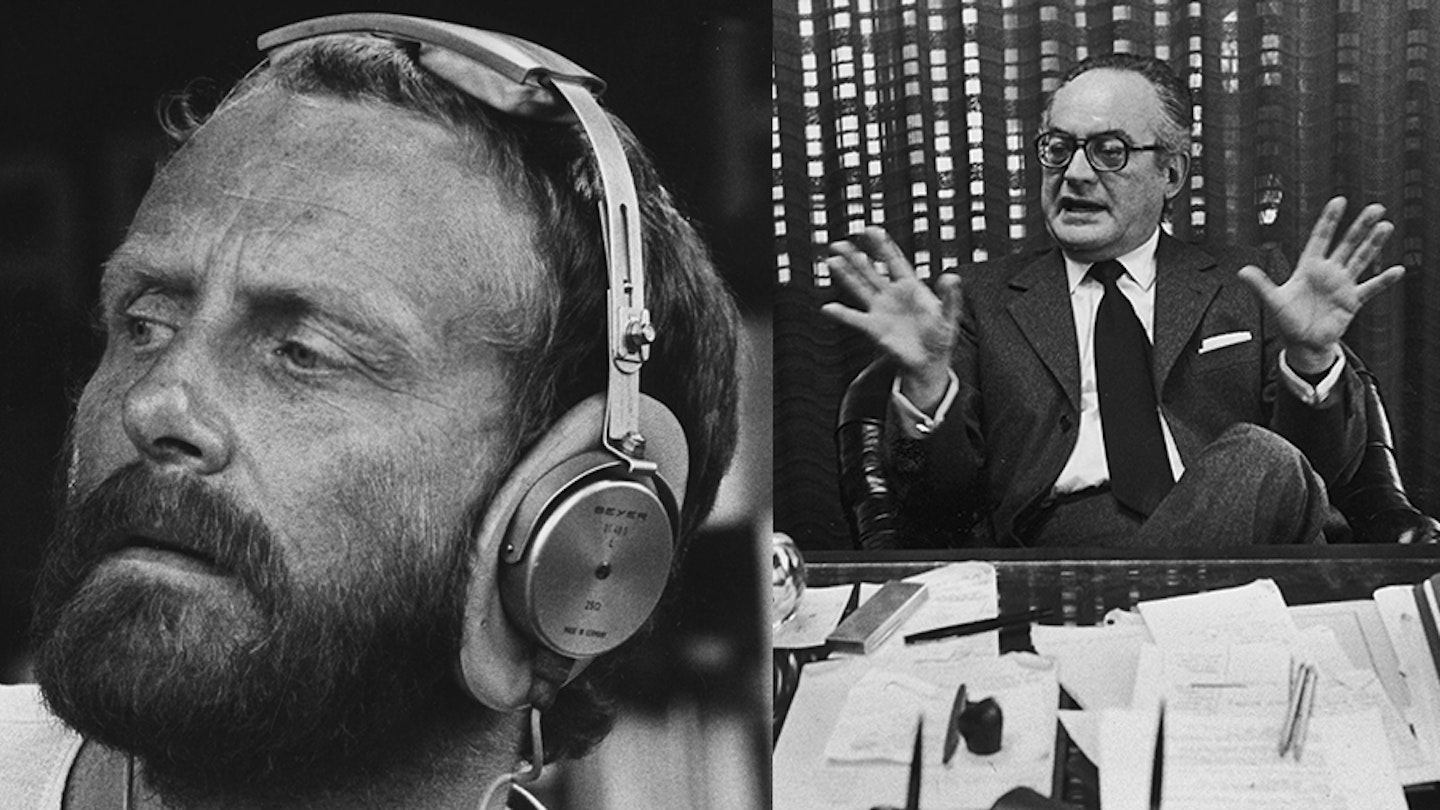

The swanky Concorde booking was a typical flourish courtesy of producer Dino De Laurentiis, an increasingly infamous European mini-mogul who appeared to have emerged straight out of central casting. De Laurentiis had arrived in Hollywood from his native Italy at the start of the decade with grand ambitions, and a seemingly endless supply of money from what were often rumoured to be dubious sources and rapidly caught and rode the wave of independent producers who were then reshaping the Hollywood landscape. Death Wish, Serpico and King Kong all bore the De Laurentiis imprimatur. Now De Laurentiis had set his imperial ambitions on Flash Gordon.

Hodges had been drafted in at the last minute. With the previous director ignominiously fired, it would now be down to Hodges, who had happily admitted to a general ignorance of both comic books and special effects, to shepherd Gordon to the big screen. As he was drawn like millions before him into the tale of the lantern-jawed championship polo player transported to the planet Mongo to do endless weekly battle with the evil Emperor Ming, a distinctly Kaiser-like despot goosed with an oriental twist via a Fu Manchu moustache, Hodges could have had no idea of the strange congruities and echoes of Flash’s trip that the one director was about to take would manifest. “As it turned out, 60,000 feet above our planet, and travelling at well over a 1000mph, was the perfect way to meet Flash for the first time. The madness,” he recalls 35 years later, “had begun".

Flash Gordon was a child of The Great Depression, the result of a circulation war between King Features, which syndicated cartoons to thousands of newspapers across the USA, and its rival, the John F. Dille Syndicate. In 1929 the Dille Syndicate had introduced its readers to Anthony "Buck” Rogers. Rattled by the time-travelling character’s immediate success, King Features had ordered Alex Raymond, a 22-year-old staff artist, to come up with something with which King Features could compete.

The winter of 1933, when Raymond and writer Don Moore began work, was a bitterly cold one even by New York standards. Outside their office temperatures plunged to minus eight and though they might have been cheered a little by the relaxing of Prohibition, it is hardly surprising that escape from the grim, chilly realities of depression life was uppermost in his mind. The first panels he and Moore worked on are, then, ablaze with colour and action: 'WORLD COMING TO END' screams a newspaper headline. 'Strange New Planet Rushing Towards Earth: Only Miracle Can Save Us!' A mere 12 frames later, with Flash and Dale secreted aboard the insane Doctor Zarkov's rocket ship, and with the words ‘To be continued’ inked in bold, Flash’s adventures on Mongo, which would endure in one form or another ever since, had begun.

It is very hard to explain just how much the coming of Flash Gordon meant to boys of my generation.

With those few pen strokes made over 80 years ago, over which Hodges had pored in a supersonic airliner that seemed to have leapt from one of its frames, it’s not unreasonable to say that Raymond wildly altered the future of pop culture. Despite his own chequered history on screen, Flash Gordon would crystalise an heroic ideal that would hold both in movies and comic books for decades to come. When Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster conceived Superman in 1938 it’s clear they looked to Raymond’s character for inspiration, inverting the Flash Gordon story, stranding their heroic alien on a fallen earth and lifting elements of Flash’s costume while they were at it. Marvel and DC’s universes are packed with superhero variations on the Flash theme. From Dan Dare to James Tiberius Kirk, Flash Gordon’s inky DNA is shot through our notions of what a hero - and superhero - is like a jagged bolt of lightning, his popularity in the pre-war years only magnified by the three Universal serials starring Larry ‘Buster' Crabbe churned out between 1936 and 1940.

But by 1956, the year Alex Raymond died in a car crash, Flash was feeling his age. The comic books, which Raymond had ceased working for at the beginning of World War II, had been almost wholly replaced in the comic-reading public's affections by the spandex-clad super men and women that Flash had helped to create. The Universal serials were consigned to TV reruns that filled time cheaply on local networks across the United States.

Including, it turned out, a small town named Modesto in Southern California. Where, two years earlier, the Lucas family had proudly installed their first television.

“Flash Gordon is such a forgotten corner of the culture, and yet if we actually listen to George Lucas, he says that people have overstated the influence of other aspects, like Kurosawa, and understated the importance of this silly little serial from the late '30s and early '40s,” Chris Taylor, author of the magisterial How Star Wars Conquered The Universe has said. If anything Taylor understates the case. Lucas tips his hat to the series he had watched on a virtual loop from the very opening frames. The iconic title crawl, its text vanishing to a point on the horizon, apes Flash Gordon Conquers The Universe right down to its quixotic four point ellipsis, as do the trademark wipe and iris cuts. Princess Leia’s soon-to-be-infamous bagel hairdo was ripped off from Queen Fria’s (you say Fria, I say Leia...) in Raymond’s Flash Gordon In The Ice Kingdom Of Mongo. Even the structure of the movie, the fact that it begins with Episode IV, owes much to the chapter-structure of the endlessly repeated television repeats that viewers would join at unexpected points. “We decided we were making a Flash Gordon-type adventure and we’re coming in at Episode IV... we’re just racing through the story, not explaining anything,” producer Gary Kurtz told Lucas biographer John Baxter.

By the early 1970s Lucas and his friend and fellow filmmaker Edward Summer were to be found sneaking into King Features, where Summer had been ordered to scan the original Raymond artwork to microfiche and destroy (the horror!) the originals. Lucas and Summer liberated them and found them new digs. And when he submitted an early draft of Star Wars the cover bore a panel from one of Raymond’s comic strips: an image of Flash and Ming, swords drawn, an almost identical scene to Obi-Wan’s final duel with Darth Vader.

Lucas’s original plan had, unsurprisingly, been to simply adapt the comic strips and so, in the early '70s, he had visited King Features to ask about the rights, where the young tyro was told that they were already thinking of a movie, one to be directed by none other than Italian maestro Federico Fellini. “He was very depressed,” Taylor reports Lucas’s friend Francis Coppola saying. “But then he says, ‘Well, I’ll just invent my own'.”

The standard genesis story of the only ‘pure’ Flash Gordon movie that would, thus far, be made, nearly a decade later in 1980, was that it was the result of De Laurentiis cashing in on the by-then unparalleled success of Star Wars. But the mention of Fellini this early indicates that in fact De Laurentiis had been thinking about a Flash Gordon project long before. Back home he had bankrolled a handful of Fellini’s films and had been on the lookout for a US project for the director. Fellini, who was rumoured to have worked on an Italian Flash Gordon knock-off comic strip after Mussolini banned the originals and had been a fan since he was a boy, first came across the strip in adventure magazine L’Avventuroso in fascist Italy. “It is very hard to explain just how much the coming of Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon meant to boys of my generation,” he says in Fellini On Fellini. “When we began to read about the astounding adventures of this galactic hero, fascism was at its height, its gloomy, dreary rhetoric in full flood. Flash Gordon, on the other hand, seemed an unbeatable hero from the very beginning, a hero who belonged to real life even though his actions took place in distant, fantastic worlds.”

Fellini eventually declined, but by 1977, with Lucas’s smash still ringing the box-office tills like no film in decades De Laurentiis decided to cash in on his option. And for a director he had a startling idea: Nicolas Roeg. “Nic was the coolest dude on the planet in those days,” recalls Michael Allin, the Enter The Dragon writer who worked for a year on the screenplay with Roeg. “He was London, he was arty, he was auteur and he knew everybody and everybody knew him. But he couldn’t crack the studios because he had such huge fucking integrity.” It might seem difficult to imagine what drew Roeg by then director of individualistic, existential masterpieces such as Walkabout and The Man Who Fell To Earth, to Flash; though the central notion of a character trapped in an alien landscape they struggle to understand certainly has resonances with the Flash Gordon story.

Flash Gordon seemed an unbeatable hero from the very beginning.

By October 1977 Roeg was sequestered in the Sunset Marquis hotel in Hollywood with long-time collaborator Allin, but the Flash Gordon movie they conceived would be very different one to the film that was finally released. “We worked for days, talking ourselves into this crazy-ass project,” recalls Allin. “Nic loved the idea that the bubbles were for the kids but the images were just so stark raving erotic. Nic’s version was going to be a comic-book story but for adults. Ming was a god. Flash and Dale were Adam and Eve, and Ming was an evil deity chasing them across the universe. Our Ming's ambition was to conquer the universe by destroying populated worlds, leaving no survivors except chosen females with whom he would populate their world in his image. Flash/Adam's task was, in Dino's words, to save-a-da-world!"

Roeg subsequently decamped to London where, through the winter and spring of 1978, a 30-strong team began work on production designs (a few of which still tantalisingly survive in the BFI Archive) while Allin ploughed through further drafts of the screenplay. De Laurentiis though, unbeknownst to either, was apparently becoming increasingly unhappy with the way the project was shaping up, even more so given the rapidly escalating budget. What had been conceived years ago as an artsy project for Fellini, and possibly offered for Roeg along those lines, was now projected to cost in the $25-$30m range. His plans to shoot the movie cheaply in Italy were scotched by that fact that his sound stages there, informally known as 'Dinocitta', had fallen into disrepair during his recent Hollywood adventures, his daughter Rafaella was the subject of Mafia kidnapping threats and the intransigent Italian labour unions refused to work weekends. After an abortive, if typically ambitious plan to buy Pinewood, De Laurentiis settled on renting 12 soundstages at Shepperton.

“A human sacrifice is required when a project is deemed to have gone wrong,” Flash Gordon’s new screenwriter Lorenzo Semple Jnr. once said of one of his own frequent firings. “It makes everybody feel good and gives the project a whole new life.” In the case of Flash he was the beneficiary of the sudden departure of Roeg, and a few weeks later, when he found that Semple had been already hired behind his back, Allin. But if Nic Roeg had been an unusual choice of director in the first place, his replacement was, in his own way, equally unlikely. Hodges, a former television director then nursing his wounds after departing The Omen II in unhappy circumstances, had established a reputation for gritty, spare movies seemingly totally at odds with the flamboyantly camp, effects-heavy demands of Semple’s new, more conventional Flash Gordon screenplay.

Once I realised the film was in many ways out my control, I relaxed and made it up as I went along. I loved it.

Having arrived in New York Hodges was confronted with legendary designer Danilo Donati, who Hodges suspects might never have got round to reading the script, who proudly unveiled his grand vision for the film’s astounding vistas in De Laurentiis’s office. Included, among other improbable marvels, was a full-scale three-lane freeway passing through the forests of Arboria. “I tentatively asked how we could possibly actually realise this,” the practically-minded director had asked De Laurentis. "We'll get McAlpine to build it," De Laurentiis declared. When Hodges pointed to the cars speeding along and enquired who would be building those, De Laurentiis had informed him he had a team from Fiat working on it.

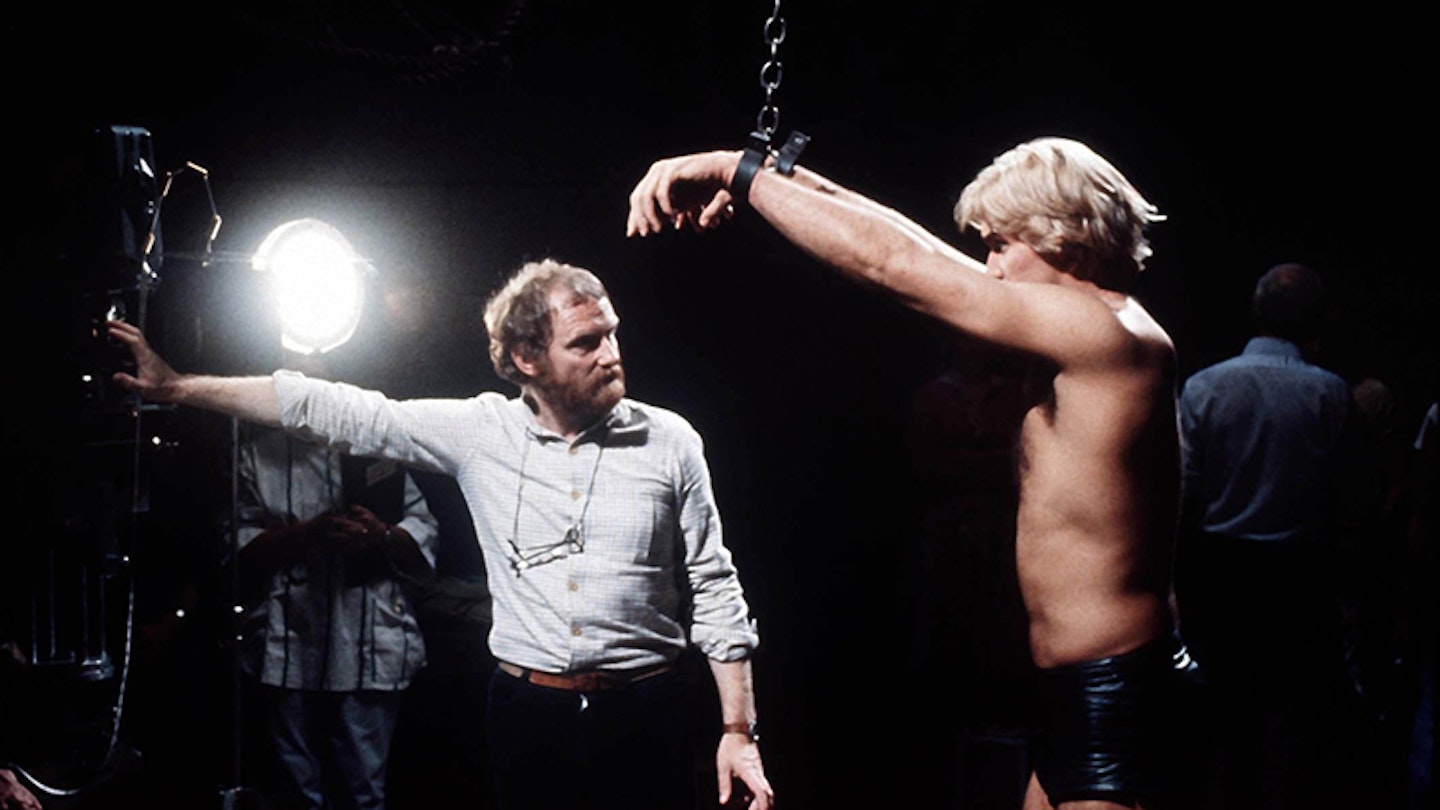

“So I had a producer who spoke mangled English and a production designer who spoke none at all. Both, like Ming, seemed to have arrived from another galaxy,” he recalls. “Once I realised the film was in many ways out my control, I relaxed and made it up as I went along. I loved it.”

Among Flash’s panoply of pleasures is one of the most eclectic casts ever assembled for a motion picture. For Flash De Laurentiis had pondered both Kurt Russell, who rejected it as too bland, and then unknown Arnold Schwarzenegger, whom he would later cast as the lead in Conan The Barbarian. “I couldn't see any name actor wanting to play Flash,” says Hodges. “He's an all-American hunk, decent, honourable, but, most importantly, naive. That's a difficult role to cast. Dino's mother-in-law saw Sam Jones (whose sole performance of note had been in Dudley Moore/Bo Derek vehicle 10) in a TV show called Hollywood Squares. We flew him to London, dyed his hair blond and that was it. Unfairly awarded many rotten tomatoes for his trouble, I think he's perfect.”

Max von Sydow arrived as a pal of De Laurentiis, as did Broadway belter Topol. “I've never seen an actor have such a good time as Max playing Ming. Cracking his finger joints and doing little jigs, he relished every moment,” smiles Hodges, while lesser roles were decanted from personal Rolodexes and theatre bars across London. “John Osborne was a mate who loved having an excuse, any excuse, not to write,” recalls Hodges of the unlikely casting of the angry young playwright as an Arborian Priest. (He had provided a similar excuse for him by casting him in Get Carter.) “I remember John was there for the first memorable day on the set of Arboria, Timothy Dalton's leafy domain. Danilo, who seemed to design sets mainly for his own personal enjoyment, had constructed trees so enormous we couldn't get the camera in.”

I told Dino, 'If you don’t give me the part I’m going to bloody kill you!

“I heard that they were doing Flash Gordon, they’d virtually cast it I think but they hadn't cast Vultan,” booms Brian Blessed to Empire about his own snagging of a role which would become career defining. “I was asked to go along and meet Mike Hodges. And there was Dino. I said, 'I’m bloody made for this. I saw it as a child. If you don’t give it to me I’m going to bloody kill you'. Well, about four weeks later he called me in again and I went to see him and Mike. And there were pictures on the wall from the comic books and they looked exactly like me. I said, ‘Look Dino! it’s bloody me!’ He said, 'No no, iza-da comic strip!’ Anyway he left me with Mike and he said, ‘They’re offering it to you, you know.’ It was £30,000, which was a bloody fortune then.”

De Laurentiis had tested dozens of actresses for the role of Dale Arden before settling on Dayle Haddon, a Canadian model who had previously graced the cover of Sports Illustrated’s legendary swimsuit issue, before unsettling on her mere days before the shoot commenced. “I had actually auditioned for the role,” Melody Anderson, then a former journalist-turned-TV-actress with guest spots on Welcome Back, Kotter and Battlestar Galactica already on her CV. “And I just went on my way, and then they called me up one day when I was in New York and said, ‘You’ve got the job but you’ve got to come over tonight.’ It was that crazy. I had to immediately go from New York. The moment I got to London they managed to dye my hair black. And we did a screen test to see how that worked and that was my first day at Shepperton.”

Flash Gordon shot for 17 weeks of principal photography and wrapped just before Christmas 1979 before reconvening for 14-week second unit shoot, during which Hodges would wrestle with the movie’s special effects. It was during this frenzied period that Sam Jones fell out with De Laurentis and embarked on an ill-advised strike, requiring Hodges to redub the dialogue he and sound mixer Ivan Sharrock couldn’t salvage with a still, despite Empire’s best efforts, unidentified vocal stand-in. The precise details of the origins of the conflict are as lost in the mists of time as the exact proportion of the redubbed lines. (About five percent says Hodges. Pretty much all of it, Jones has claimed.)

But the row would have unfortunate aftershocks. With Jones unable to perform publicity duties the film’s subsequent press campaign was underpowered, particularly in the US, which had knock-on effects. “One of the biggest injustices was that the we were not even nominated for costume or sets, and they were so brilliant,” recalls Anderson, now a practicing psychotherapist. “Universal had kind of pulled back because their were issues working with Dino and the whole thing with Sam. It all got political. To think that it was not even nominated for production design! It was really unfortunate and unnecessary, as most conflicts are. It was a clash of the egos to an extent.”

A human sacrifice is required when a project is deemed to have gone wrong.

Meanwhile De Laurentiis, in a genuine masterstroke, decided to furnish the film with a rock score. “I had wanted to have Pink Floyd,” admits Hodges. “Dark Side Of The Moon was blaring on the set when Queen came to visit. Very embarrassing. They were Dino's idea. A better choice: lighter, more humorous, more range.”

Flash was released to generally good reviews and mixed box office on December 5, 1980. In the subsequent 35 years attempts to revive Flash have come to not very much at all. A much discussed but apparently greenlight-proof remake has been on the cards for decades, passing via the groaning desk of Ridley Scott in the early 2000’s to Breck Eisner, whose disastrous Sahara in 2005 killed both his involvement in big-budget action and his mooted star, Matthew McConaughey’s chances of ever playing the role. Currently it resides with self-confessed devotee Matthew Vaughn. In 2007 Sci-Fi, in a naked attempt to reproduce the success of Superman spin-off Smallville, delivered its series Flash, which ran for a solitary season.

But despite this, the Son of Mongo still almost single-handedly animates the current box office. Star Wars would be unthinkable without him, and what then is J.J. Abrams' reboot, Disney’s theme-parks and newly minted continuing universe but a four billion dollar tribute? Marvel and DC’s much-mined universes are populated with heroes of many flavours, but all a variation of some sort or another on the template that Alex Raymond established nearly 90 years ago. He haunts the current esprit du movies like the tantalising gap between the words 'The End' and solitary question mark. Absent in person, perhaps, but very much alive.